William Wilkinson | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 1819[1] |

| Died | 1901[1] |

| Nationality | British |

| Occupation | Architect |

| Practice | Wilkinson and Moore (from 1881) |

| Buildings | Randolph Hotel, Oxford; Shelswell Park, Shelswell, Oxfordshire |

| Projects | St Edward's School, Oxford; Norham Manor Estate, Oxford |

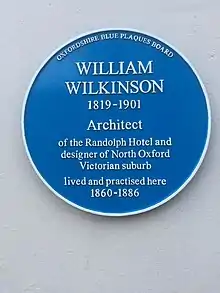

William Wilkinson (1819–1901) was a British Gothic Revival architect who practised in Oxford, England.

Family

Wilkinson's father was a builder in Witney in Oxfordshire.[2] William's elder brother George Wilkinson (1814–1890) was also an architect, as were William's nephews C.C. Rolfe (died 1907) and H.W. Moore (1850–1915).[1]

Career

Most of Wilkinson's buildings are in Oxfordshire. His major works include the Randolph Hotel in Oxford, completed in 1864. He was in partnership with his nephew H.W. Moore[1] from 1881.[3] In his long career Wilkinson had a number of pupils, including H.J. Tollit (1835–1904).[4]

Works

Churches

In 1841, at the age of only 22, Wilkinson designed a new Church of England parish church, Holy Trinity at Lew, Oxfordshire.[5] His other work on churches included:

- St Leonard's parish church, Eynsham: restoration, 1856[6]

- Witney Cemetery: lodge and two chapels, 1857[7]

- Witney Workhouse: chapel, 1860[8]

- All Saints' parish church, Middleton Cheney, Northamptonshire: Horton family mausoleum, 1866–67[9]

- St Andrew's parish church, Headington, Oxford: added north aisle, 1880[10]

Police buildings

Wilkinson moved to Oxford in 1856 and succeeded J.C. Buckler as architect to the local police committee.[2] Oxfordshire County Constabulary was formed in 1857, and Wilkinson designed several buildings for the new force.

- Watlington police station, 1858–59[11]

- Witney police station, 1860[7]

- Woodstock police station, 1863[12]

- Chipping Norton police station, 1864–65[13]

- Burford police station, 1869[14]

- Magistrates' room at Deddington Court House, 1874[15]

Houses

Wilkinson designed Home Farm on the Shirburn Castle estate, built in 1856–57.[16] From 1860 he laid out the Norham Manor estate in north Oxford.[17][18] The estate was slowly developed with large villas, a number of which Wilkinson designed himself.[19] Wilkinson also designed town houses and small country houses elsewhere in Oxfordshire:

- Hollybank, Wootton, 1862–63[20]

- 10, Broad Street, Oxford, 1863[21]

- Whittlebury, Northamptonshire: farmhouse, 1864[22]

- The Holt, Middleton Cheney, Northamptonshire, 1864[9]

- 60 Banbury Road, Oxford, 1865–66[23]

- Bignell House, Chesterton, 1866 (partly demolished)[24]

- 23 and 24 Cornhill, Banbury, 1866[25]

- Astrop Park, Northamptonshire: lodge, pheasantry and cottage, 1868[26]

- Witney Almshouses: restoration, 1868.[27]

- Brashfield House, Caversfield, 1871–73[28]

- Shelswell Park, Shelswell, 1875[29]

- Cowley Place (now St Hilda's College, Oxford): extension, 1877–78[30][31]

Clergy houses

A number of the houses that Wilkinson designed were for clergy. Most were for the Church of England, but he also designed a presbytery that was built for the Roman Catholic Church.

- Ramsden parsonage, 1862[32]

- Chadlington parsonage, 1863 (now Chadlington House)[33]

- Duns Tew rectory, 1864 (now Priory Court)[34]

- Godington parsonage, 1867 (now the Old Vicarage)[35]

- Upper Heyford parsonage, 1869[36]

- Rousham rectory: enlargement and remodelling, 1873.[37]

- St Aloysius' presbytery, Woodstock Road, Oxford, 1877–78[38]

- Combe vicarage and Institute (with H.W. Moore), 1892–93[39]

Educational establishments

Wilkinson designed the library for the Oxford Union, built in 1863.[40] He designed a number of schools, of which the largest was St Edward's School, Oxford, whose buildings he completed in phases from 1873 until 1886.[41][42] His other schools include:

Industrial buildings

Late in his career Wilkinson undertook one industrial commission: a new smith shop and foundry for William Lucy's Eagle Ironworks in Jericho, Oxford. This single-storey building was completed in 1879.[48] It was demolished after Lucy ceased production in England in 2005.[49]

Publications

- Wilkinson, William (1875) [1870]. English Country Houses: Sixty-one Views and Plans of Recently Erected Mansions, Private Residences, Parsonage-Houses, Farm-Houses, Lodges, and Cottages; with Sketches of Furniture and Fittings; and a Practical Treatise on House-Building (second ed.). London: James Parker and Co.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 Brodie et al. 2001, p. 994.

- 1 2 Tyack 1998, p. 234.

- ↑ Tyack 1998, p. 267.

- ↑ Woolley 2010, p. 71.

- ↑ Sherwood & Pevsner 1974, pp. 682–683.

- ↑ Sherwood & Pevsner 1974, p. 600.

- 1 2 Sherwood & Pevsner 1974, p. 846.

- ↑ Sherwood & Pevsner 1974, p. 851.

- 1 2 Pevsner & Cherry 1973, p. 306.

- ↑ Sherwood & Pevsner 1974, p. 336.

- ↑ Sherwood & Pevsner 1974, p. 830.

- ↑ Sherwood & Pevsner 1974, p. 857.

- ↑ Sherwood & Pevsner 1974, p. 539.

- ↑ Sherwood & Pevsner 1974, p. 509.

- ↑ Sherwood & Pevsner 1974, p. 572.

- ↑ Sherwood & Pevsner 1974, p. 763.

- ↑ Tyack 1998, pp. 234–235.

- ↑ Sherwood & Pevsner 1974, p. 317.

- ↑ Sherwood & Pevsner 1974, p. 318.

- ↑ Sherwood & Pevsner 1974, p. 860.

- ↑ Sherwood & Pevsner 1974, p. 313.

- ↑ Pevsner & Cherry 1973, p. 461.

- ↑ Sherwood & Pevsner 1974, p. 319.

- ↑ Sherwood & Pevsner 1974, p. 618.

- ↑ Sherwood & Pevsner 1974, p. 440.

- ↑ Pevsner & Cherry 1973, p. 529.

- ↑ Sherwood & Pevsner 1974, p. 847.

- ↑ Sherwood & Pevsner 1974, p. 524.

- ↑ Sherwood & Pevsner 1974, p. 753.

- ↑ Tyack 1998, p. 323.

- ↑ Sherwood & Pevsner 1974, p. 245.

- ↑ Sherwood & Pevsner 1974, p. 734.

- ↑ Sherwood & Pevsner 1974, p. 525.

- ↑ Sherwood & Pevsner 1974, p. 591.

- ↑ Sherwood & Pevsner 1974, p. 613.

- ↑ Sherwood & Pevsner 1974, p. 821.

- ↑ Crossley 1983, pp. 159–168.

- ↑ Sherwood & Pevsner 1974, pp. 289, 332.

- ↑ Sherwood & Pevsner 1974, p. 553.

- ↑ Sherwood & Pevsner 1974, p. 273.

- ↑ Tyack 1998, p. 238.

- ↑ Sherwood & Pevsner 1974, p. 332.

- ↑ Townley 2004, pp. 254–255.

- ↑ Sherwood & Pevsner 1974, p. 710.

- ↑ Sherwood & Pevsner 1974, p. 510.

- ↑ Sherwood & Pevsner 1974, p. 809.

- ↑ Sherwood & Pevsner 1974, p. 343.

- ↑ Woolley 2010, pp. 85, 86.

- ↑ Woolley 2010, p. 87.

Sources

- Brodie, Antonia; Felstead, Alison; Franklin, Jonathan; Pinfield, Leslie; Oldfield, Jane, eds. (2001). Directory of British Architects 1834–1914, L–Z. London & New York: Continuum. p. 994. ISBN 0-8264-5514-X.

- Crossley, Alan (ed.); Baggs, A.P.; Colvin, Christina; Colvin, H.M.; Cooper, Janet; Day, C.J.; Selwyn, Nesta; Tomkinson, A. (1983). A History of the County of Oxford. Victoria County History. Vol. 11: Wootton Hundred (northern part). London: Oxford University Press for the Institute of Historical Research. pp. 159–168. ISBN 978-0-19722-758-9.

{{cite book}}:|first1=has generic name (help) - Pevsner, Nikolaus; Cherry, Bridget (revision) (1973) [1961]. Northamptonshire. The Buildings of England (2nd ed.). Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-071022-1.

- Saint, Andrew (1970). "Three Oxford Architects". Oxoniensia. Oxfordshire Architectural and Historical Society. XXXV: 53 ff. Retrieved 3 November 2009.

- Sherwood, Jennifer; Pevsner, Nikolaus (1974). Oxfordshire. The Buildings of England. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-071045-0.

- Townley, Simon C. (ed.); Baggs, A.P.; Chance, Eleanor; Colvin, Christina; Cooper, Janet; Day, C.J.; Selwyn, Nesta; Williamson, Elizabeth; Yates, Margaret (2004). A History of the County of Oxford. Victoria County History. Vol. 14: Witney and its Townships: Bampton Hundred (Part Two). Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer for the Institute of Historical Research. pp. 254–255. ISBN 978-1-90435-625-7.

{{cite book}}:|first1=has generic name (help) - Tyack, Geoffrey (1998). Oxford An Architectural Guide. Oxford & New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-817423-3.

- Woolley, Liz (2010). "Industrial Architecture in Oxford, 1870 to 1914". Oxoniensia. Oxfordshire Architectural and Historical Society. LXXV: 67–96. ISSN 0308-5562.