| Wat Damnak វត្តដំណាក់ | |

|---|---|

Front porch of Wat Damnak | |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Theravada Buddhism |

| Location | |

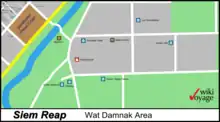

| Location | Siem Reap |

| Country | Cambodia |

Shown within Cambodia | |

| Geographic coordinates | 13°21′06″N 103°51′28″E / 13.3517°N 103.8578°E |

| Architecture | |

| Completed | 1927 |

Wat Domnak is a famous Buddhist pagoda and one of the teaching monasteries in the city of Siem Reap, Cambodia.

Etymology

The name of Wat Domnak commemorates the fact that this pagoda was a former residence (Damnak, in Khmer, ព្រះដំណាក់ ) of the monarchy of Cambodia.

History

From royal residence to a Buddhist monastery for learned monks

Wat Damnak was formerly the royal residence of King Sisowath from 1904 to 1927. Later, the king's palace was relocated near the Banana King Ashram. After the Royal Palace was relocated, the courtyard of the old palace complex was turned into a Buddhist pagoda.

The first Abbot, Preah Dhammacariyeavangs Et, is depicted as a conservative Buddhist monk by the Kambujasuriya in 1927, holding on to his palm-leaf manuscript rather than printed books.[1]

In 1935, Venerable Prin Tim was chosen to be the new chief of the pagoda, for which he built not only the current pagoda building of Wat Damnak but also the youth hostel. In fact, after he was called to oversee all of the pagodas of the province of Siemreap after 1939, he was responsible for the creation of numerous schools in the region.[2]

The youth hostel was part of the larger movement of building youth hostels encouraged by the 20 June 1936 law of the Front populaire led by Léon Blum in France, and it was developed in Cambodia hoping that it would "lead Cambodian youth to travel and so broaden the mind". The first youth hostel in the neighbourhood of Wat Damnak had Prince Sutharot as its honorary president. In December 1939, Khmer civil servant and playwright penned a played called Indra s'ennuie (Indra is bored) staging the descent of Indra on earth, for him to realize that the real paradise was near Woat Domnak, at the youth hostel in Siem Reap.[3]

In the 1950s, the monks of Wat Damnak erected some stupas in the courtyard of the pagoda on the model of Banteay Srei, following the advice of archaeologist Henri Marchal, of the French School of the Far East.[4]

In 1974, the statues of Preah Ang Chek Preah Ang Chorm which had been worshipped by the infamous Dap Chhuon, were sheltered within the compound in the monastery in order to protect it from the destruction caused by the Cambodian Civil War, their later fate being controversial.[5]

Military base of the Khmers rouges

During the Khmers Rouges regime, Wat Damnak was used by the Khmers Rouges as their military base. When the Khmer Rouges entered Siem Reap on 17 April 1975, the revolutionary committee was formed at Wat Damnak. The next day, Venerable Put Ponn and two other monks were escorted to attend a celebration in honour of their coup. The monks were required to say the traditional prayer celebrating victory.[6]

Breaking the most fundamental monastic rules, monks were seen carrying guns at Wat Domnak as a gun-toting monk was nominated district chief.[7]

In order to regenerate the monastic order after its dispersion, Tep Vong performed ordinations of new monks in September 1979 at Wat Domnak.[8]

Recovering the statue of Yey Deb

During the Khmer Rouge period the statue of Yay Deb was broken into pieces and thrown into a pond in nearby Wat Damnak. The Yay Deb statue, virtually identical to the leper king exhibited at the National Museum, apart from not having fangs. Thought to be contemporaneous with the leper king, Yay Deb was found by early researchers at Wat Kling Rangsei, a Buddhist pagoda built on a pre-Angkorean temple site south of the Western Baray. Like many other statues at the time, Yay Deb's baromey is said to have prevented the iconoclasts from totally destroying her or from dragging her far from her seat of power. Having recovered the different pieces in 1985, Siem Reap residents, including the staff of the Angkor Conservation Office, transferred the reconstituted statue from Wat Damnak to its original spot under a bodhi tree where it used to stand. Since the head had entirely disappeared, in 1988 the conservation office molded a replica in cement and attached it to the ancient stone body. Mistaken for an ancient original, this head was stolen soon thereafter. The conservation office attached a new cement head, which remains today.[9]

This loss was compensated by the construction of a new stupa to host a relic of Buddha, a rite of installation done in various other pagodes across Cambodia and encouraged by lay Buddhist teacher and political influencer Buth Savong.[10]

Becoming a center for study

Wat Domnak is one of the teaching monasteries of Siem Reap, and this academic ambition has developed considerably since the early 2000s.

The Center for Khmer Studies was founded in 1999 as an initiative of the World Monuments Fund, an international NGO in the field of preservation. . Wat Damnak to host the center as a central location and a traditional place of learning.[11]

In 2001, Wat Damnak was among other sites in Cambodia to be considered part of the Buddhist heritage at risk "sometimes ancient, and little known".[12]

In 2005 the monks of Wat Damnak founded the Life and Hope Association (LHA), a non-profit, non-governmental, and non-political organization which was part of a new movement of Buddhist social work in Cambodia.[13]

An international conference, the first of its kind on the history of medicine in Southeast Asia was held in January 2006 at Wat Damnak Monastery.[14]

In mid December 2007, archaeologists, ceramic experts, historians, researchers, teachers and artists came together in Siem Reap, Cambodia, for an international conference titled Ancient Khmer and Southeast Asian Ceramics at the Center for Khmer Studies in the grounds of Wat Damnak.[15]

Architecture

Wat Damnak has a low front section with columns or pillars over the entire eastern facade of the sanctuary, typical of the first half of the twentieth century.

The railings have balusters of the western type - so-called pear balusters which are most common of that period. The wall was pierced with vertical ovals arranged at a rhythm identical to that of the balusters.

The capitals have western moldings. While the capitals of the pillars usually have classical moldings and do not meet Western criteria, we note the isolated case of Vat Damnak, where the capitals of the two small columns fluted shaft of the porch are of a composite style, with a foliated basket and Ionic capital volutes.

The simple arched doorframe is inspired by Western architectural decor. This representation, much less common than those of Angkorian pediments, developed during the reign of Sisowath, as if the observation of colonial buildings had gradually inspired the builders of sanctuaries.

On the five doors and the fourteen shutters of the sanctuary of Damnak, there are series of historiated scenes of the Reamker including remarkable bas-reliefs, by their number and the subjects treated as by their quality. The decoration with a red and gold background, illustrating historiated scenes from the Reamker, is very elaborate and of great finesse. It is a testimony of ancient techniques drawing traditional Khmer motifs in the shape of flowers or flame.

The bai sema leaves, generally decorated with a bas-relief, are only decorated in their middle with a full vertical molding, a simple rod, a sign of their antiquity.[16]

Education and research

Pali School

Today, Wat Domnak is not only a Buddhist temple for monks to practice and for Buddhists to perform rituals, but this pagoda is also a center of study. Lessons are given for monks to study Pali, Sanskrit and Dharma. In addition, the pagoda also has a primary school for children to study. In addition, every day, many people go to read books or do homework there.

Center for Khmer Studies

Separately, in the pagoda, there is also an institution called Center for Khmer Studies open for the public to study, research documents and read books.

Tourism

Wat Damnak has long attracted tourists to its neighbourhood, with the first youth hostel opening in the 1930s.

This touristic development has led to some criticism, as younger generations who train in classical dance at Wat Damnak, are encouraged to turn the traditional dances of Cambodia into a tourist show.[17]

Gastronomy

The famous roast beef around Wat Damnak has been on sale for more than two decades, dating back to the 1990s. Different from the roast beef in Phnom Penh with long skewers, the famous roast beef around Wat Damnak has short and rather flat bamboo skewers. The lean beef at the end is turned upside down with a spicy red sauce.[18] The pagoda has also given its name to Cambodia's most acclaimed restaurant Cuisine Wat Damnak, run by French chef Joannès Rivière, set up in the vicinity of the pagoda.[19]

References

- ↑ Kent, Alexandra; Chandler, David Porter (2008). People of Virtue: Reconfiguring Religion, Power and Moral Order in Cambodia Today. NIAS Press. p. 35. ISBN 978-87-7694-037-9.

- ↑ Souverains et notabilités d'Indochine (in French). Editions du Gouvernement général de l'Indochine (impr. I.D.E.O.). 1943. p. 91.

- ↑ Edwards, Penny (1 January 2007). Cambodge: The Cultivation of a Nation, 1860-1945. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 229–230. ISBN 978-0-8248-2923-0.

- ↑ MARCHAL, Henri (1954). "Note sur la forme du stupa au Cambodge". Bulletin de l'École française d'Extrême-Orient. 44 (2): 581–590. doi:10.3406/befeo.1951.5187. ISSN 0336-1519. JSTOR 43732089.

- ↑ Thik, Kaliyann (23 September 2011). "The guardian statues". Phnom Penh Post. Retrieved 18 July 2022.

- ↑ Mertha, Andrew C. (6 February 2014). Brothers in Arms: Chinese Aid to the Khmer Rouge, 1975–1979. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-7072-1.

- ↑ Harris, Ian (31 December 2012). Buddhism in a Dark Age: Cambodian Monks under Pol Pot. University of Hawaii Press. p. 71. ISBN 978-0-8248-6577-1.

- ↑ Harris, Ian (31 December 2012). Buddhism in a Dark Age: Cambodian Monks under Pol Pot. University of Hawaii Press. p. 203. ISBN 978-0-8248-6577-1.

- ↑ Marston, John (30 June 2004). History, Buddhism, and New Religious Movements in Cambodia. University of Hawaii Press. p. 111. ISBN 978-0-8248-2868-4.

- ↑ Marston, John (1 May 2015). "Buth Savong y la nueva proliferación de reliquias en Camboya". Estudios de Asia y África. 50 (2): 265. doi:10.24201/eaa.v50i2.2204. ISSN 2448-654X.

- ↑ "The Center for Khmer Studies", Cultural Renewal in Cambodia, BRILL, pp. 91–114, 17 August 2020, doi:10.1163/9789004437357_008, ISBN 978-90-04-43735-7, S2CID 240730628, retrieved 31 July 2021

- ↑ Miura, Keiko (2011), "World Heritage Making in Angkor", World Heritage Angkor and Beyond, Göttingen University Press, pp. 9–31, doi:10.4000/books.gup.304, ISBN 978-3-86395-032-3, retrieved 31 July 2021

- ↑ Chhon, Kimpicheth (2019). "Life and Hope Association: Engaged Buddhist Strategy Transforming Compassion into Social Action". International Journal of Multidisciplinary in Management and Tourism. 3 (2): 105–118. ISSN 2730-3306.

- ↑ Jones, Margaret (2014). "Global Movements, Local Concerns: Medicine and Health in Southeast Asia ed. by Laurence Monnais and Harold J. Cook (review)". Bulletin of the History of Medicine. 88 (4): 755–756. doi:10.1353/bhm.2014.0084. ISSN 1086-3176. S2CID 74218574.

- ↑ Calthorpe, Jane (2008). "Pepper and rice and all things nice". Ceramics Technical (27): 57–60.

- ↑ Guéret, Dominique Pierre. Les monastères bouddhiques du Cambodge : caractéristiques des sanctuaires antérieurs à 1975. OCLC 940503323.

- ↑ Tuchman-Rosta, Celia (2014). "From Ritual Form to Tourist Attraction: Negotiating the Transformation of Classical Cambodian Dance in a Changing World". Asian Theatre Journal. 31 (2): 524–544. doi:10.1353/atj.2014.0033. ISSN 1527-2109. S2CID 143124740.

- ↑ ស្រីនាង, ឈឹម. "សាច់គោអាំង ១៥០០ រៀលមួយចង្កាក់ល្បី នៅវត្តដំណាក់ខេត្តសៀមរាប". www.postkhmer.com. Retrieved 31 July 2021.

- ↑ Junker, Ute (1 April 2019). "Cuisine Wat Damnak, Cambodia: How this French chef transformed local cuisine". Traveller. Retrieved 31 July 2021.

Bibliography

- Tainturler, Francois (2004). "Wat Damnak, Siem Reap-Angkor: Conserving built heritage in a Cambodian Buddhist monastery". Historic Environment. 17 (3): 12–15.