%252C_297.jpg.webp) | |

| Original title | 魏志倭人傳 |

|---|---|

| Country | Western Jin dynasty |

| Language | Classical Chinese |

| Genre | History |

| Published | Between 280 and 297 |

| Preceded by | Records of the Three Kingdoms, volume 29 |

| Followed by | Records of the Three Kingdoms, volume 31 |

| Wajinden | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese name | |||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 魏志倭人傳 | ||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 魏志倭人传 | ||||||

| |||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||

| Kanji | 魏志倭人伝 | ||||||

| |||||||

The Wajinden (倭人伝; "Treatise on the Wa People") are passages in the 30th fascicle of the Chinese history chronicle Records of the Three Kingdoms that talk about the Wa people, who would later be known as the Japanese people. It describes the mores, geography, and other aspects of the Wa, the people and inhabitants of the Japanese archipelago at the time. The Records of the Three Kingdoms was written by Chen Shou of the Western Jin dynasty at the end of the 3rd century (between the demise of Wu in 280 and 297, the year of Chen Shou's death).[1]

Overview

There is no independent treatise called "Wajinden" in the Records of the Three Kingdoms, and the description of Yamato is part of the Book of Wei, vol. 30, "Treatise on the Wuhuan, Xianbei, and Dongyi". The name "Wajinden" comes from Iwanami Bunko who published the passages under the name Gishi Wajinden (魏志倭人伝) in 1951.[2] Therefore, some believe that it is meaningless unless one reads not only the passages on the Wa but also the whole of the Treatise on the Dongyi ("Eastern Barbarians").[3] Yoshihiro Watanabe, a researcher of the Three Kingdoms, states that the accounts about the Korean Peninsula and Japan were not based on Chen Shou's first-hand experience, but was written based on rumors and reports from people who had visited the Korean Peninsula and Japan, and its authenticity is questionable. He further recommended that "the worldview and political situation of Chen Shou be examined not only by reading the Records and its annotations in full, but also by familiarizing with the Confucian classics that form the worldview to understand it.".[4]

The Wajinden represents the first time a comprehensive article about the Japanese archipelago has been written in the official history of China. The Dongyi treatise in the Book of the Later Han is chronologically earlier than the Wajinden, but the Wajinden was written earlier.[5]

The book describes the existence of a country in Wa (some say later Japan) at that time, centered on the country of Yamatai, as well as the existence of countries that did not belong to the queen, with descriptions of their locations, official names, and lifestyles. This book also describes the customs, flora and fauna of the Japanese people of the time, and serves as a historical record of the Japanese archipelago in the 3rd century.

However, it is not necessarily an accurate representation of the situation of the Japanese archipelago at that time,[6] which has been a cause of controversy regarding Yamatai[7] On the other hand, there are also some researchers such as Okada Hidehiro who cast doubt on the value of the Wajinden as a historical document. Okada stated that there were large discrepancies in the location and mileage and that it lacked credibility.[8] Takaraga Hisao said, "The Wajinden is not complete, and it cannot be regarded as a contemporaneous historical material because of the lack of total consistency and the long transcription period.[9] Although it is certain that the Book of Wei predates the Records of the Three Kingdoms, there are many errors in the surviving anecdotes. In addition, Yoshihiro Watanabe stated that the Wajinden contains "many biases (distorted descriptions) due to the internal politics and diplomacy of Cao Wei at the time when Himiko sent her envoy and the world view of the historian.[4]

Editions

Of the printed versions of the Wajinden that have survived, the one included in the Bainaben (百衲本; "patchwork") version of the Twenty-Four Histories from the 20th century during the Republican period of China is considered the best. The edition of Records of the Three Kingdoms that forms the Bainaben version is based on a copy from the Shaoxi period (紹熙; 1190–1194) of Southern Song dynasty.[10]

A punctuated edition of the Records of the Three Kingdoms was published in 1959 by Zhonghua Book Company in Beijing, and is available in Japan. In addition, Kodansha published a kanbun version named Wakokuden (倭国伝) in 2010 featuring syntactic markers to aid the Japanese reader.[11]

The Wajinden was written without paragraphs, but it is divided into six paragraphs in the Chinese-language versions and the Kodansha version. In terms of content, it is understood to be divided into three major sections.[12]

Relationship between Wa and Wei

Himiko and Toyo

Originally, there was a male king for 70 to 80 years, but there was a prolonged disturbance in the whole country (considered as the so-called "Civil War of Wa"). In the end, the confusion was finally quelled by appointing Himiko, a woman, as the ruler.

Himiko was described to be a shaman queen who held her people under a spell. She was elderly and had no husband. Her younger brother assisted her in the administration of the kingdom. She had 1,000 attendants, but only one man was allowed in the palace to serve food and drink and to take messages. The palace was strictly guarded by a guard of soldiers.

Himiko sent a messenger to Wei through Daifang Commandery in 238, and was appointed by the emperor as the King of Wa, Ally to Wei. In 247, Daifang dispatched Zhang Zheng (張政) to negotiate a peace between Wa and Kununokuni. According to the description in Wajinden, he exchanged messengers with the countries of the Korean Peninsula.

When Himiko died in 247, a mound was built and 100 people were buried there. After that, a male king was established, but the whole country did not accept him, and more than 1,000 people were killed. After the death of Himiko, a 13-year-old Toyo, a girl of Himiko's clan or sect, was appointed as ruler and the country was pacified. Zhang Zheng, who had been dispatched to Japan earlier, presented Toyo with a proclamation, and Toyo also sent an envoy to Wei.

Diplomacy with the Wei and Jin dynasties

- In June of the second year of the Jingchu era (238), the Queen sent her husband, Natome (難升米), and her second emissary, Tsushigori (都市牛利), to Daifang commandery to request an audience with the son of heaven.[lower-alpha 1] In December, the emperor Cao Rui was pleased and proclaimed the queen as the King of Wei, bestowed a gold seal and purple ribbon, gave her a huge gift including 100 bronze mirrors, and named Natome as the General of the Household (中郎將).

- In 240, the Grand Administrator of Daifang, Gong Zun (弓遵), dispatched a group of emissaries to Japan with an imperial decree and ribbons, temporarily conferred the title of King of Japan, and gave them gifts.

- In 243, the queen again sent an envoy to Wei, this time with a group of slaves and cloth. The emperor Cao Fang made them Generals of the Household .

- In 245, the emperor Cao Fang issued an imperial decree to send a yellow banner to Nanshōme through Daifang. However, this was not carried out, as the Grand Administrator Gong Zun was killed in battle against the Eastern Ye.

- In 247, a new Grand Administrator, Wang Qi (王頎), arrived in office. The queen sent a messenger to report on the war against Kununokuni. This was not based on the report from Japan in the same year, but on an edict issued in 245.

- After assuming the queen's throne, Toyo (it is possible that the queen was already Toyo at the time of the dispatch in 247) had 20 people accompany Zhang Zheng's return to China.

In addition, the "Jingū-ki" in Nihon Shoki quotes the now-lost Imperial Diaries of Jin (晉起居注) that the queen of Wa presented tribute through interpreters in October of 266. The extant Book of Jin notes that the Wa made a tribute in November of 266 in the annals of the Emperor Wu of Jin. The embassy was recorded elsewhere in the Book of Jin in the "Biography of the Four Barbarians" (四夷傳), although the Wa ruler was not specified to be a queen. It is probable that Toyo made a tribute to Emperor Wu of Jin, who overthrew the Wei.

The Wa afterwards

After the record of Toyo's tribute in the mid-3rd century, there would be no record of Japan in Chinese historical books for nearly 150 years until the tribute of King San (one of the five kings of Wa) in 413. The Gwanggaeto Stele fills in this gap, stating that in 391 people from Wa crossed the sea to invade Baekje and Silla, and battled with Gwanggaeto of Goguryeo.

The text

According to the Wajinden, the Wa people made the mountainous island as their state, and paid tribute to the continent through the Daifang Commandery that was established by the Han dynasty near present-day Seoul.

As for the route from Daifang Commandery to Japan, the passages relating to the Korean peninsula in fascicle 30 of the Records of the Three Kingdoms describes the location and boundaries of Samhan and Wa to the south of Daifang Commadery:

The Han (Korea) is south of Daifang, bounded by the sea to the east and west, connecting with Wa to its south, with an area of 4,000 li. There are three Han, the first is called Mahan, the second is called Jinhan, the third is called Byeonhan.

The Book of the Later Han's treatise on the Dongyi makes the positional relationship of Samhan more concrete:

Mahan is to the west, consisting of 54 chiefdoms, bordering Lelang to the north and Wa to the south. To the east is Jinhan, with twelve chiefdoms, bordering Yemaek to the north. Byeonhan is south of Jinhan, consisting of twelve chiefdoms of its own, also bordering Wa in the south.

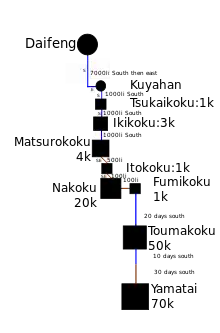

The journey to Yamatai

There are various theories about official names.

An excerpt of ![]() the original text and an English translation (romanizations mainly follow J. Edward Kidder).[13]

the original text and an English translation (romanizations mainly follow J. Edward Kidder).[13]

| Original Chinese | English translation |

|---|---|

| 倭人在帶方東南大海之中、依山㠀爲國邑.舊百餘國、漢時有朝見者.今使譯所通三十國. | The Wa lived in the seas southeast of Daifang, and established chiefdoms in the mountains and islands. It originally had more than 100 chiefdoms. During the Han dynasty, there were those who came to see the Emperor, and now there are thirty chiefdoms that have been in contact with envoys and interpreters. |

| 從郡至倭、循海岸水行、歷韓國、乍南乍東、到其北岸狗邪韓國、七千餘里. | In order to reach Wa from the [Daifang] commandery, one must follow the coast and go through Han (Mahan), heading to the south and east, to reach Geumgwan Gaya on its (Wa's) northern shore, 7,000 li from the commandery. |

| 始度一海千餘里、至對馬國、其大官曰卑狗、副曰卑奴母離、所居絶㠀、方可四百餘里.土地山險、多深林、道路如禽鹿徑.有千餘戸.無良田、食海物自活、乗船南北市糴. | After crossing the sea for the first time for more than 1,000 li, one arrives at Tsushima chiefdom. The governor was called hiko. His second-in-command was called hinamori. They are on an island in the middle of nowhere, about 400 li in every direction. The land is mountainous and heavily wooded, and the roads are like the paths of birds and deer. There are more than 1,000 houses. There are no good rice fields, so they subsist by eating marine products and taking boats to the north and south to buy rice. |

| 又南渡一海千餘里、名曰瀚海、至一大國.官亦曰卑狗、副曰卑奴母離.方可三百里.多竹木叢林.有三千許家.差有田地、耕田猶不足食、亦南北市糴. | Crossing the sea again for more than a thousand li south, the sea named the Vast Sea (Tsushima Strait), one arrives in Idaikoku (Iki). Its top official is again named hiko and his second-in-command hinamori. The distance in all directions was about three hundred li. There are many bamboo groves and thickets, and more than 3,000 houses. There is a little rice field, and even after cultivating the field, there is not enough to eat, so they go north and south to buy rice. |

| 又渡一海千餘里、至末廬國.有四千餘戸、濱山海居.草木茂盛、行不見前人.好捕魚鰒、水無深淺、皆沈没取之. | After crossing another sea for more than 1,000 li, one arrives at Matsuro chiefdom. There are more than 4,000 houses. They live on the coast between the mountains and the sea. They live on the shore between the mountains and the sea, where the vegetation is so thick that they cannot see the people in front of them as they walk. They like to catch fish and abalone, and whether the water is deep or shallow, they all dive for them. |

| 東南陸行五百里、到伊都國.官曰爾支、副曰泄謨觚・柄渠觚.有千餘戸.丗有王、皆統屬女王國.郡使往來常所駐. | Five hundred li to the southeast, and one arrives at Ito chiefdom. The official is called niki. The second-in-commands are called imoko and hikoko. There were more than 1,000 houses, ruled by a hereditary king, all belonging to the queen's domain. This was the place where the travelling envoys of the commandery stayed. |

| 東南至奴國百里.官曰兕馬觚、副曰卑奴母離.有二萬餘戸. | A hundred miles to the southeast is the Na chiefdom. The official is called shimako. The second-in-command is called hinamori. There are more than 20,000 houses. |

| 東行至不彌國百里.官曰多模、副曰卑奴母離.有千餘家. | Eastward for a hundred miles is the Fumi chiefdom. The official is called tamo. The second-in-command is called hinamori. There are more than 1,000 families. |

| 南至投馬國、水行二十曰.官曰彌彌、副曰彌彌那利.可五萬餘戸. | It takes twenty days of water travel southward to get to the Toma chiefdom. The official was called mimi. The second-in-command was called miminari. There are more than 50,000 houses. |

| 南至邪馬壹國、女王之所都、水行十日、陸行一月. 官有伊支馬、次曰彌馬升、次曰彌馬獲支、次曰奴佳鞮.可七萬餘戸. | Going south, one will reach the country of Yamatai, the capital of the queen. It takes ten days by water and one month by land. The official is ikima, subordinates mimato, mimawaki, and nakato. There are more than 70,000 houses. |

Other chiefdoms

Other than the chiefdoms mentioned on the journey from Daifang to the Queen's domain in Yamatai, there are other distant countries that are only known by name. In addition, mention is made of a Kona chiefdom south of Yamatai ruled by a male king that lies outside of the Queen's control.

An excerpt of ![]() the original text and an English translation follows:

the original text and an English translation follows:

| Original Chinese | English translation |

|---|---|

| 自女王國以北、其戸數道里可得略載、其餘旁國遠絶、不可得詳. 次有斯馬國、次有已百支國、次有伊邪國、次有都支國、次有彌奴國、 次有好古都國、次有不呼國、次有姐奴國、次有對蘇國、次有蘇奴國、 次有呼邑國、次有華奴蘇奴國、次有鬼國、次有爲吾國、次有鬼奴國、 次有邪馬國、次有躬臣國、次有巴利國、次有支惟國、次有烏奴國、次有奴國. 此女王境界所盡. | North from the Queen's domain, the distance and number of households can only be roughly estimated, but the rest of the chiefdoms are too far away and cannot be known in detail. In order, the chiefdoms are Shima, Ihaki, Iya, Toki, Mina, Kokoto, Fuko, Sona, Tsuso, Sona, Ko-o, Kanasona, Ki, Igo, Kina, Yama, Kuji, Hari, Kii, Una, then Na. Here the Queen's realm is exhausted. |

| 其南有狗奴國.男子爲王、其官有狗古智卑狗.不屬女王. | In the south there is the chiefdom of Kona, which has a man as its king. The official therein is Kukochihiko. It does not belong to the Queen. |

Distance from Daifang Commandery to Yamatai

| 自郡至女王國、萬二千餘里. | The distance from Daifang Commandery to the Queen's country is 12,000 li. |

Descriptions of Wa

Excerpts from ![]() the original text and an English translation:

the original text and an English translation:

| Original Chinese | English translation |

|---|---|

| 男子無大小、皆黥面文身. | All men, high or low, have their faces and bodies inked. |

| 自古以來、其使詣中國、皆自稱大夫. | In the past, when emissaries visited China, they all called themselves taifu. |

| 夏后少康之子、封於會稽、斷髪文身、以避蛟龍之害.今倭水人好沈没捕魚蛤、文身亦以厭大魚水禽、後稍以爲飾. | The son of Shaokang of Xia was enfeoffed in Kuaiji. He cut off his hair and inked his body to avoid harm from the flood dragon. The water people of Wa are fond of diving to catch fish and clams, with inked bodies to ward off large fish and aquatic fowl. Later, the ink was used as a decoration. |

| 諸國文身各異、或左或右、或大或小、尊卑有差. | Each chiefdom's ink is different: they may be to the left or right, large or small, depending on the status of the person. |

| 計其道里、當在會稽東冶之東. | Taking into account the distance of the journey, it should be east of Dongye of Kuaiji. |

| 其風俗不淫.男子皆露紒、以木緜頭.其衣橫幅、但結束相連、略無縫.婦人被髪屈紒、作衣如單被、穿其中央、貫頭衣之. | The custom was not lewd. All the men wear their topknots uncovered, with cotton cloths draped over their heads. Their clothes are made of wide strips of cloth tied together, with little or no sewing. The women's hair was tied in a knot, and their clothes were made like a single-layered robe with a hole in the middle, through which they stuck their heads. |

| 種禾稻・紵麻、蠶桑緝績、出細紵・縑・緜. | They plant grains, rice, flax, and mulberry trees for silkworms. Linen, silk, and cotton are spun to make textiles. |

| 其地無牛馬虎豹羊鵲. | There are no cattle, horses, tigers, leopards, sheep, or magpies in the land. |

| 兵用矛・楯・木弓.木弓短下長上、竹箭或鐵鏃或骨鏃.所有無與儋耳・朱崖同. | For weapons, they use spears, shields, and wooden bows. Wooden bows are shorter at the bottom and longer at the top, and the arrows are made with bamboo with iron or bone arrowheads. Their haves and have-nots are the same as the Dan'er and Zhuya commanderies. |

| 倭地温暖、冬夏食生菜、皆徒跣. | The land of Wa is warm, and people eat fresh vegetables in both winter and summer. Everyone is barefoot. |

| 有屋室、父母兄弟臥息異處.以朱丹塗其身體、如中國用粉也.食飲用籩豆、手食. | There are houses, and the parents and siblings have different places to sleep and rest. The body is covered with red ochre, similar to the use of powder in China. When eating and drinking, they use a high bowl and eat with their hands. |

| 其死、有棺無槨、封土作冢.始死停喪十餘曰.當時不食肉、喪主哭泣、他人就歌舞飲酒.已葬、擧家詣水中澡浴、以如練沐. | When a person dies, there is a coffin but no outer casing, and a mound is made by sealing the coffin with earth. During this period, the mourners do not eat meat, and the mourners weep and cry, while the others sing, dance, and drink. After the burial, the whole family goes into the water to purify the body. This is similar to the practice of ablution. |

| 其行來渡海詣中國、恒使一人、不梳頭、不去蟣蝨、衣服垢汚、不食肉、不近婦人、如喪人.名之爲持衰.若行者吉善、共顧其生口財物.若有疾病、遭暴害、便欲殺之、謂其持衰不謹. | Whenever a mission crosses the sea to China, there would always be a man who does not comb his head, not remove lice, not eat meat, and not let women come near him, as if he were a mourner. He is called a jisai. If the journey is blessed with good luck, he will be given slaves and goods. If the journey is met with disease or misfortune, they will kill him for the jisai is said to be disrespectful. |

| 出真珠・青玉.其山有丹、其木有柟・杼・櫲樟・楺・櫪・投橿・烏號・楓香、其竹篠・簳・桃支.有薑・橘・椒・蘘荷、不知以爲滋味.有獼猴・黒雉. | Wa produces pearls and jasper. Their mountains have cinnabar, their trees are mountain camphor, horse-chestnut, camphor tree, Japanese quince, Quercus serrata oak, cryptomeria, Quercus dentata oak, mulberry, and maple. Their bamboos are sasa, arrow bamboo, and vine bamboo. They have ginger, citrus, pepper, and myoga, yet they do not know their taste. There are also monkeys and black pheasants. |

| 其俗舉事行來、有所云爲、輒灼骨而卜、以占吉凶.先告所卜、其辭如令龜法、視火坼占兆. | When embarking on an endeavour or a journey, the custom is to burn the bones and divine good or bad fortune. The diviner first announces the occasion to be divined. The words are like in tortoise bone divination, in which the fire cracks are examined for oracles. |

| 其會同坐起、父子男女無別.人性嗜酒.見大人所敬、但搏手以當跪拝.其人壽考、或百年、或八九十年. | There is no distinction between father and son, male and female, when it comes to sitting together. People like to drink. To show respect, the aristocrats just clap their hands in place of kneeling down. People live a long life, perhaps a hundred years old, or eighty or ninety. |

| 其俗、國大人皆四五婦、下戸或二三婦.婦人不淫、不妒忌.不盗竊、少諍訟.其犯法、輕者没其妻子、重者滅其門戸及宗族.尊卑各有差序、足相臣服. | According to the custom, every man of high rank in the country has four or five wives, and every man of low rank has two or three wives. The women are not licentious, nor jealous. There is no thievery and litigations are few. If they violate the law, persons who committed minor offences will have their wives and children enslaved, and those who committed major crimes will have their families and clans destroyed. There is a hierarchical order, with lower classes subjected to supervision by the higher ones. |

| 收租賦、有邸閣. | There are mansions where taxes are collected. |

| 國國有市、交易有無使大倭監之.自女王國以北、特置一大率、檢察諸國、諸國畏憚之.常治伊都國、於國中有如刺史. | There are markets in each chiefdom, and trade was conducted with the supervision of a Wa official. In the north of the Queen's domain stations an Ichidaisotsu who conducts inspections of the chiefdoms, striking fear in them. He governs from Ito chiefdom, and is like a cishi (Inspector) in the country. |

| 王遣使詣京都、帶方郡、諸韓國.及郡使倭國、皆臨津捜露、傳送文書、賜遣之物詣女王、不得差錯. | In the occasion when the ruler sends an envoy to our capital (Luoyang), Daifang commandery, or the various Han (Korean) states; or when the commandery sends an envoy to Wa, they must be searched at the ports and have their messages and gifts to the queen delivered without fail. |

| 下戸與大人相逢道路、逡巡入草.傳辭說事 或蹲或跪 兩手據地 爲之恭敬 對應聲曰噫 比如然諾 | When a commoner meets an aristocrat on the street, he modestly steps into the grass. If they are to address the aristocrat, they are to crouch or kneel, hands on the ground, in an attitude of reverence. When responding, they say "ai" in affirmation. |

| 其國本亦以男子爲王、住七八十年、倭國亂、相攻伐歷年、乃共立一女子爲王、名曰卑彌呼.事鬼道、能惑衆、年已長大、無夫壻、有男弟佐治國.自爲王以來、少有見者、以婢千人自侍、唯有男子一人、給飲食、傳辭出入.居處宮室、樓觀、城柵嚴設、常有人持兵守衞. | Originally, the country was ruled by a man for seventy or eighty years. Then Wa descended into chaos as the chiefdoms attacked each other for many years. Finally, the chiefdoms together decided on making a woman as ruler. Her name is Himiko. She was adept at shamanism and kept the people under her spell. She remained unmarried even though advanced in age, but had a brother who assisted her in ruling the land. Since she became queen, she has not had many visitors, and has 1,000 female servants to attend to her. There is only one man who serves food and drink, delivers messages, and enters and exits the palace. Her palace and terraces are heavily stockaded and normally protected by armed guards. |

| 女王國東渡海千餘里、復有國、皆倭種.又有侏儒國在其南、人長三四尺、去女王四千餘里、又有裸國、黒齒國、復在其東南、船行一年可至. | To the east of the Queen's domain, more than a thousand li across the sea, there are yet another chiefdoms all like the Wa. To their south is the Land of the Dwarves, where the inhabitants are three or four chi in height. More than four thousand li away from the Queen's domain, there are the Land of the Naked and the Land of the Black Teeth. They are to the southeast of the Land of the Dwarves, and they can be reached by ship in a year. |

| 参問倭地、絶在海中洲㠀之上、或絶或連、周旋可五千餘里. | To visit all the lands of Wa, all dwelling on islands in the middle of the ocean that are sometimes isolated and sometimes continuous, would take more than five thousand li to complete a circuit. |

Chronology

Contains excerpts from ![]() the original text. and an English translation

the original text. and an English translation

| Original Chinese | English translation |

|---|---|

| 景初二年六月 倭女王遣大夫難升米等詣郡 求詣天子朝獻 太守劉夏遣吏將送詣京都 | In the sixth month of the second year of the Jingchu era (238 AD), the Queen of Wa sent a delegation with the taifu Natome to the commandery (Daifang) seeking audience with the son of heaven and present him with an offering. Liu Xia, the grand administrator, sent officials to take them to the capital (Luoyang). |

| 其年十二月 詔書報倭女王 曰(中略) | In the twelfth month of that year, in an imperial decree, the Queen of Wa was informed that:

(decree enumerating the tributes received and the gifts and titles bestowed to Wa in reciprocation omitted) |

| 正始元年 太守弓遵遺建中校尉梯儁等 奉詔書印綬詣倭國 拜假倭王 并齎詔賜金帛 錦 罽 刀 鏡 采物 倭王因使上表答謝詔恩 | In the first year of the Zhengshi era (240 AD), the grand administrator Gong Zun sent a delegation with the Colonel Establishing Centrality Ti Jun to go to Wa with an imperial decree, a seal, and a purple ribbon to present to the ruler of Wa. Alongside were gifts of gold, white silk, embroidered silk, woolen cloth, swords, mirrors, and other things. The ruler of Japan sent an envoy in response thanking the emperor's favor. |

| 其四年 倭王復遺使大夫伊聲耆 掖邪狗等八人 上獻生口 倭錦 絳青縑 緜衣 帛布 丹木拊 短弓矢 掖邪狗等壹拜率善中郎將印綬 | In the fourth year [of Zhengshi] (244 AD), the Wa ruler again sent eight envoys, including taifu Itogi and Yayako, to present slaves, Japanese brocades, red and blue silk, wadded clothes, white silk, cinnabar, a bow grip, and a short bow and arrows. Yayako and several of his entourage received seals and ribbons bearing the rank of the General of the Household Leading the Virtuous. |

| 其六年 詔賜倭難升米黃幢 付郡假授 | In the sixth year (246 AD), the emperor issued an decree to bestow yellow banners to Natome of Wa, to be presented at the commandery (Daifang). |

| 其八年 太守王頎到官 倭女王卑彌呼與狗奴國男王卑彌弓呼素不和 遺倭載斯 烏越等詣郡 說相攻擊狀 遣塞曹掾史張政等 因齎詔書 黃幢 拜假難升米 爲檄告喻之 卑彌呼以死 大作冢 徑百餘歩 狥葬者奴碑百餘人 更立男王 國中不服 更相誅殺 當時殺千餘人 復立卑彌呼宗女壹與年十三爲王 國中遂定 政等以檄告喻壹與 壹與遣倭大夫率善中郎將掖邪狗等二十人 送政等還 因詣臺 獻上男女生口三十人 貢白珠五千孔 青大句珠二枚 異文雜錦二十匹 | In the eighth year (248 AD), the grand administrator Wang Qi arrived to his post. The Queen of Wa, Himiko, had been in conflict with Himikoko, the male king of Kona. She sent Wa's Kishiuo and others to the commandery to explain their conflict. Zhang Zheng, the Deputy Officer of the Border Guard, and others were dispatched to present Natome with a decree and yellow banners along with a document admonishing them.

When Himiko died, a large mound was built. The diameter of the mound was more than a hundred paces, and there were more than a hundred servants who were sacrificed. A male king succeeded her, but the whole country refused to obey him. They fought in deadly feuds with each other, killing more than 1,000 people at the time. A 13-year-old female relative of Himiko named Iyo, was installed as ruler, and the whole country was finally pacified. Zhang Zheng and others admonished Iyo with a proclamation. Iyo sent 20 men, including the Wa taifu Yayako, the Gentleman of the Household Leading the Virtuous, to escort Zhang Zheng back to China and to present slaves and gifts of 5,000 white pearls, two large blue beads, and 20 brocades with different designs. |

It is important to note that the Wei imperial decrees were dated to the time they were written, not the time they arrived in Wa, which typically took two years to arrive.

The "Yamatai controversy" over its location

Following the distance in Wajinden exactly as they were written would land a hypothetical traveller past the Japanese archipelago and into the Pacific Ocean.[14] As such, there is considerable debate over the locations of the Wa chiefdoms named in the Wajinden, primarily Yamatai. The prevailing theories are the "Honshu Theory" and the "Kyushu Theory". The interpretations of the journey to Yamatai are split into the "continuous theory" and the "radiation theory" (see Yamatai).

Textual relationship with other sources

Book of Later Han

There is a description about Wa in Fan Ye's Book of Later Han written in the 5th century. Its contents have much in common with the Wajinden, but it also includes details that are absent from Wajinden such as the approximate time-frame of the Civil War of Wa, which the Book of Later Han records to be during the reign of Emperor Huan and Ling (146–189).

Book of Sui

The passages about Wa in the 7th century Book of Sui are seen as a compilation of similar passages from the Weilüe, Wajinden, Book of Later Han, Book of Song, and the Book of Liang. As such, many passages from Wajinden can be found in the Book of Sui with minor modifications. Notably, the Book of Sui updated the distances found in Wajinden.[15]

Footnotes

- ↑ Yao Silian's Book of Liang, vol. 54, "The Various Barbarians", gives the year of the embassy as the 3rd year of Jingchu (239). as does the Wo passages in fascicle 782 of Taiping Yulan. Wei did not take control of Daifang Commandery until the beginning of 238, after Liu Xin (劉昕) was appointed as the Grand Administrator of Daifang and sent to occupy the area according to the Biography of Gongsun Yuan in the Records of the Three Kingdoms. For these reasons, the Kodansha Bunko (2010) states that the year 238 here is an error in the Records (Tōdō, Takeda & Kageyama 2010).

References

- ↑ (Furuta 1971).

- ↑ (Wada & Ishihara 1951), (Ishihara 1985)

- ↑ (Matsumoto 1968)

- 1 2 (Watanabe 1985)

- ↑ (Tōdō, Takeda & Kageyama 2010)

- ↑ (Nishio 1999), (Nishio 2009a)

- ↑ Okamoto (1995)

- ↑ Okamoto (1995, p. 76) illustrates the Okada theory

- ↑ Hōga, Toshio (宝賀寿男).「邪馬台国論争は必要なかった-邪馬台国所在地問題の解決へのアプローチ-」 Kokigi no heya. 2015.

- ↑ Furuta (1971) contains a photocopy of the Wajinden. It is also included in the 1985 edition of the Iwanami Bunko compilation.

- ↑ (Tōdō, Takeda & Kageyama 2010)

- ↑ Yoshimura (2010, pp. 8) is a recent example

- ↑ Kidder, Jonathan Edward (2007). Himiko and Japan's elusive chiefdom of Yamatai: archaeology, history, and mythology. Honolulu (T.H.): University of Hawai'i press. ISBN 978-0-8248-3035-9.

- ↑ Okamoto 1995, p. 89.

- ↑ Ishihara 1985, p. 65.

Bibliography

- Okamoto, Kenichi (1995). Yamataikoku ronsō 邪馬台国論争. Kōdansha sensho mechie. Tōkyō: Kōdansha. ISBN 978-4-06-258052-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link)

- Tōdō, Akiyasu; Takeda, Akira; Kageyamaō, Terukuni (2010). 倭国伝 中国正史に描かれた日本. 講談社学術文庫 2010. Kōdansha. ISBN 978-4-06-292010-0.

- Nishio, Kanji (1999). Kokumin no rekishi. Atarashii-Rekishi-Kyōkasho-o-Tsukuru-Kai. Tōkyō: Sankei Shinbun Nyūsu Sābisu. ISBN 978-4-594-02781-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Nishio, Kanji (2009). 国民の歴史(上) 決定版. 文春文庫. 文藝春秋. ISBN 978-4-16-750703-9.

- Furuta, Takehiko (November 1971). 「邪馬台国」はなかった 解読された倭人伝の謎. 朝日新聞社.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Matsumoto, Seichō (1968). 古代史疑. 中央公論社. ASIN B000JA64RY.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Yoshimura, Takehiko (November 2010). ヤマト王権 シリーズ 日本古代史②. 岩波新書(新赤版)1272. 岩波書店. ISBN 978-4-00-431272-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Wada, Sei; Ishihara, Michihiro, eds. (November 1951). 魏志倭人伝・後漢書倭伝・宋書倭国伝・隋書倭国伝. 岩波文庫. 岩波書店. ASIN B000JBE2JU.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Ishihara, Michihiro, ed. (1985). 魏志倭人伝・後漢書倭伝・ 宋書倭国伝・隋書倭国伝――中国正史日本伝1. Iwanami-bunko (Shintei, dai 58 satsu hakkō ed.). Tōkyō: Iwanami-Shoten. ISBN 978-4-00-334011-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Watanabe, Yoshihiro (May 2012). 魏志倭人伝の謎を解く 三国志から見る邪馬台国. 中公新書 2164. 中央公論新社. ISBN 978-4-12-102164-9.