|

| Part of a series on |

| Violin |

|---|

| Violinists |

| Fiddle |

| Fiddlers |

| History |

| Musical styles |

| Technique |

| Acoustics |

| Construction |

| Luthiers |

| Family |

A violin consists of a body or corpus, a neck, a finger board, a bridge, a soundpost, four strings, and various fittings. The fittings are the tuning pegs, tailpiece and tailgut, endpin, possibly one or more fine tuners on the tailpiece, and in the modern style of playing, usually a chinrest, either attached with the cup directly over the tailpiece or to the left of it. There are many variations of chinrests: center-mount types such as Flesch or Guarneri, clamped to the body on both sides of the tailpiece, and side-mount types clamped to the lower bout to the left of the tailpiece.

Body

The body of the violin is made of two arched plates fastened to a "garland" of ribs with animal hide glue. The ribs are what is commonly seen as the "sides" of the box. The rib garland includes a top block, four corner blocks (sometimes omitted in inexpensively mass-produced instruments,) a bottom block, and narrow strips called linings, which help solidify the curves of the ribs and provide extra gluing surface for the plates. From the top or back, the body shows an "hourglass" shape formed by an upper bout and a lower bout. Two concave C-bouts between each side's corners form the waist of this figure, providing clearance for the bow.

The best woods, especially for the plates, have been seasoned for many years in large wedges, and the seasoning process continues indefinitely after the violin has been made. Glue joints of the instrument are held with hide glue since other adhesives can be difficult or impossible to reverse when future repairs are in order. Parts attached with hide glue can be separated when needed by using heat and moisture or careful prying with a thin knife blade. A well-tended violin can outlive many generations of violinists, so it is wise to take a curatorial view when caring for a violin.

Top

Typically the top (also known as the belly or table, in the U.K.) -- the soundboard) is made of quarter-sawn spruce, bookmatched at a strongly glued joint down the center, with two soundholes (or "f-holes", from their resemblance to a stylized letter "f") precisely placed between the C-bouts and lower corners. The soundholes affect the flex patterns of the top and allow the box to breathe as it vibrates. A decorative inlaid set of three narrow wooden strips, usually a light-colored strip surrounded by two dark strips, called purfling, runs around the edge of the top and is said to give some resistance to cracks originating at the edge. It is also claimed to allow the top to flex more independently of the rib structure. Some violins have two lines of purfling or knot-work type ornaments inlaid in the back. Painted-on faux purfling on the top is usually a sign of an inferior violin. A slab-sawn bass bar fitted inside the top, running lengthwise under the bass foot of the bridge, gives added mass and rigidity to the top plate. Some cheaper mass-produced violins have an integral bass bar carved from the same piece as the top. Ideally the top is glued to the ribs and linings with slightly diluted hide glue to allow future removal with minimal damage.

Back and ribs

The back and ribs are typically made of maple, most often with a matching striped figure, called "flame." Backs may be one-piece slab-cut or quarter-sawn or bookmatched two-piece quarter-sawn. Backs are also purfled, but in their case the purfling is less structurally important than for the top. Some fine old violins have scribed or painted rather than inlaid purfling on the back. The small semicircular extension of the back known as the "button" provides extra gluing surface for the crucial neck joint and is neglected when measuring the length of the back. Occasionally a half-circle of ebony surrounds the button, either to restore material lost in resetting the neck of an old instrument, or to imitate that effect.

The ribs, having been bent to shape by heat, have their curved shape somewhat reinforced by lining strips of other wood at the top and bottom edges. The linings also provide additional gluing surface for the seams between the plates (top and bottom) and the rib edges.

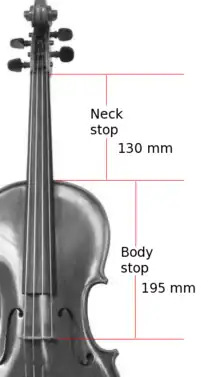

Neck

The neck is usually maple with a flamed figure compatible with that of the ribs and back. It carries the fingerboard, typically made of ebony, but often some other wood stained or painted black. Ebony is considered the preferred material because of its hardness, appearance, and superior resistance to wear. Some very old violins were made with maple fingerboards carrying a veneer of ebony. At the peg end of the fingerboard sits a small ebony or ivory nut, infrequently called the upper saddle, with grooves to position the strings as they lead into the pegbox. The scroll at the end of the pegbox provides essential mass to tune the fundamental body resonance and provides a convenient grip for spare fingers to brace against when tuning one-handed (with the violin on the shoulder). Some "scrolls" are carved representations of animal or human heads instead of the classical spiral volute most normally seen. The maple neck alone is not strong enough to support the tension of the strings without distorting, relying for that strength on its lamination with the fingerboard. For this reason, if a fingerboard comes loose, as may happen, it is vital to loosen the strings immediately. The shape of the neck and fingerboard affect how easily the violin may be played. Fingerboards are dressed to a particular transverse curve and have a small lengthwise "scoop" or concavity, slightly more pronounced on the lower strings, especially when meant for gut or synthetic strings. The neck is not varnished, but is polished and perhaps lightly sealed to allow ease and rapidity of shifting between positions.

Some old violins (and some made to appear old) have a grafted scroll or seam between the pegbox and neck. Many authentic old instruments have had their necks reset to a slightly increased angle and lengthened by about a centimeter. The neck graft allows the original scroll to be kept with a Baroque violin when bringing its neck to conformance with modern standard.

Bridge

The bridge is a precisely cut piece of maple, preferably with prominent medullary rays, showing a flecked figure. The bridge forms the lower anchor point of the vibrating length of the strings and transmits the vibration of the strings to the body of the instrument. Its top curve holds the strings at the proper height from the fingerboard, permitting each string to be played separately by the bow. The mass distribution and flex of the bridge, acting as a mechanical acoustic filter, have a prominent effect on the sound.

Blank, back side

Blank, back side Finished back

Finished back Blank, front side

Blank, front side Finished front

Finished front

Tuning the violin can cause the bridge to lean, usually toward the fingerboard, as the tightening of the strings pulls it. If left that way, it may warp. Experienced violinists know how to straighten and center a bridge.

Sound post and bass bar

The sound post or "soul post" fits precisely between the back and top, just to the tailward side of the treble bridge foot. It helps support the top under string pressure and has a variable effect on the instrument's tone, depending on its position and the tension of its fit. Part of adjusting the tone of the instrument is moving the sound post by small amounts laterally and along the long axis of the instrument using a tool called a sound post setter. Since the sound post is not glued and is held in place by string tension and being gently wedged between the top and back, it may fall over if all the strings are slackened at once.

Running under the opposite side of the bridge is the bass bar. While the shape and mass of the bass bar affect tone, it is fixed in position and not so adjustable as the sound post. It is fitted precisely to the inside of the instrument at a slight angle to the centre joint. On many German trade instruments it used to be common fashion not to fit a bass bar but to leave a section of the front uncarved and shape that to resemble one. During the baroque era, bass bars were much shorter and thinner.

Tailpiece

The tailpiece may be wood, metal, carbon fiber, or plastic, and anchors the strings to the lower bout of the violin by means of the tailgut, nowadays most often a loop of stout nylon monofilament that rides over the saddle (a block of ebony set into the edge of the top) and goes around the endpin. The endpin fits into a tapered hole in the bottom block. Most often the material of the endpin is chosen to match the other fittings, for example, ebony, rosewood or boxwood.

Very often the E string will have a fine tuning lever worked by a small screw turned by the fingers. Fine tuners may also be applied to the other strings and are sometimes built into the tailpiece. Fine tuners are usually used with solid metal or composite strings that may be difficult to tune with pegs alone; they are not used with gut strings, which have greater flexibility and don't respond adequately to the very small changes in tension of fine tuners. Some violinists, particularly beginners or those who favor metal strings, use fine tuners on all four strings. Using a fine tuner on the E string or built-in fine tuners limits the extent to which their added mass affects the sound of the instrument.[1]

Pegs

_for_violin_made_from_ebony_wood.jpg.webp)

At the scroll end, the strings ride over the nut into the pegbox, where they wind around the tuning pegs. Strings (which are usually flatwound) usually have a colored "silk" wrapping at both ends for identification and to provide friction against the pegs, as well as protect the windings. The peg shafts are shaved to a standard taper, their pegbox holes being reamed to the same taper, allowing the friction to be increased or decreased by the violinist applying appropriate pressure along the axis of the peg while turning it. Various brands of peg compound or peg dope help keep the pegs from sticking or slipping. Peg drops are marketed for slipping pegs. Pegs may be made of ebony, rosewood, boxwood, or other woods, either for reasons of economy or to minimize wear on the peg holes by using a softer wood for the pegs.

Attempts have been made to market violins with machine tuners, but they have not been generally adopted primarily because earlier designs required irreversible physical modification of the pegbox, making violinists reluctant to fit them to classical instruments, and they added weight at the scroll. Early examples included large geared pegs that required much larger holes and/or bracing bars and additional holes, and tuning machines resembling those on a double bass, with metal plates screwed to the sides of the pegbox. Recent advances in machining technology have allowed the creation of several types of internally geared pegs the same size as the usual wooden pegs, requiring no more modification than would be seen in any peg replacement.

Bow

The bow consists of a stick with a ribbon of horsehair strung between the tip and frog (or nut, or heel) at opposite ends. At the frog end, a screw adjuster tightens or loosens the hair. The frog may be decorated with two eyes made of shell, with or without surrounding metal rings. A flat slide usually made of ebony and shell covers the mortise where the hair is held by its wedge. A metal ferrule holds the hair-spreading wedge and the shell slide in place. Just forward of the frog, a leather grip or thumb cushion protects the stick and provides grip for the violinist's hand. Forward of the leather, a winding serves a similar purpose, as well as affecting the balance of the bow. The winding may be wire, silk, or whalebone (now imitated by alternating strips of yellow and black plastic.) Some student bows, particularly the ones made of solid fiberglass, substitute a plastic sleeve for grip and winding.

The stick was traditionally made of pernambuco - the heartwood of the brazilwood tree - but due to overharvesting and near extinction at its original source, other woods and materials, such as ironwood or graphite, are more commonly used. Some student bows are made of fiberglass. Recent innovations have allowed carbon-fiber to be used as a material for the stick at all levels of craftsmanship. The hair of the bow traditionally comes from the tail of a white male horse, although some cheaper bows use synthetic fiber. The hair must be rubbed with rosin occasionally so it will grip the strings and cause them to vibrate;[2] new or unrosined bow hair simply slides and produces no sound. Bow hair is regularly replaced when the ribbon becomes skimpy or unbalanced from hair breakage or bow bug damage or the violinist feels the hair has "lost its grip."

Strings

Violins have four strings, usually tuned to G, D, A, and E. The strings run from a tailpiece attached to the base, across a wooden bridge, continue towards the neck of the instrument running parallel to the fingerboard, and connect to the pegbox located at the very top of the violin. They are wound around four tuning pegs that are mounted sideways through holes in the pegbox. The bridge helps to hold the strings in place, while the pegs maintain the tension necessary to produce vibration.

Strings were first made of sheep's intestines (called "catgut"), stretched, dried and twisted. Contrary to popular belief, violin strings were never made of cat's intestines. Gut strings are used in modern and "period" music, though in recent years the "baroque" historically accurate performance violinists seem to use them more often than those who play later period music or baroque music in a "modern" style. Gut strings are made by a number of specialty string makers as well as some large stringmaking companies.

In the 19th century (and even earlier though not yet prevalent) metal windings were developed for the lower-pitched gut strings. Wound strings avoid the flabby sound of a light-gauge string at low tension. Heavier plain-gut strings at a suitable tension are inconvenient to play and difficult to fit into the pegbox.

There are many claims made that gut strings are difficult to keep in tune. In fact for those who have experience with them, plain gut strings are quite stable from a tuning standpoint. Wound gut has more instability of tuning due to the different response to moisture and heat between the winding and the core and from string to string. Some players use olive oil on gut strings to extend their playing life and improve tuning stability by reducing their sensitivity to humidity. Gut strings tend to hold their sound quality nicely right up until they fail or become excessively worn.

Modern strings are most commonly either a stranded (arranged in single thin lengths twisted together) synthetic core wound with various metals, or a steel core, which may be solid or stranded, often wound with various other metals. With low-density cores such as gut or synthetic fiber, the winding allows a string to be thin enough to play, while sounding the desired pitch at an appropriate tension. The winding of steel strings affects their flexibility and surface properties, as well as mass. Strings may be wound with several layers, in part to control the damping of vibrations, and influence the "warmth" or "brightness" of the string by manipulating the strength of its overtones.

The core may be synthetic filaments, solid metal, or braided or twisted steel filaments. The uppermost E string is usually solid steel, either plain or wound with aluminium in an effort to prevent "whistling." Gold plating delays corrosion of the steel and may also reduce whistling. Stainless steel gives a slightly different tone. Synthetic-core strings, the most popular of which is Perlon (a trade name for stranded nylon) combine some of the tonal qualities of gut strings with greater longevity and tuning stability. They are also much less sensitive to changes in humidity than gut strings, and less sensitive to changes in temperature than all-metal strings. Solid-core metal strings are stiff when newly replaced and tend to go out of tune quickly.

While some gut strings still use a knot to secure the tail end in the slot of the tailpiece, most modern strings use a "ball", a small bead often made of bronze. A frequent exception is the E string, which may be had with either a ball or loop end, since the smallest E-string fine tuners hold the tail of the string on a single small hook.

The price of different string types varies dramatically; gut and gut-core strings are typically the most expensive, followed by leading synthetic core brands, and student steel strings at the lowest price range. Natural gut strings (without the metal windings) are quite inexpensive, especially for the E and A strings. The longevity of strings (all types) is highly variable and influenced by style of play, chemistry of perspiration and its interaction with the string material, presence of fingernails, frequency of play etc. Some players have trouble with certain brands of strings or one particular string from a brand but not with others.

The character of the sound produced by the strings can be adjusted quite markedly through the selection of different types of strings. The most noticeable divisions of sound quality for violins is steel, artificial gut ("perlon" core etc.), wound gut, and plain gut. The wound gut tend to have a mellow sound, as do many of the artificial strings, though other artificial core strings are specifically designed to be "bright". Steel and plain gut are both rather bright (full of overtones) but in distinctly different ways: It is possible to tell the difference and yet each is livelier or brighter typically than the wound soft-core and wound-gut strings. Certain styles of music have come to be played with certain types of strings, yet there is no hard and fast rule in this respect as each musician is looking for his or her sound. (Country fiddling is often on steel or all-metal; orchestral and solo is often wound (gut or artificial) with a steel e; baroque or early music may be played rather more than romantic pieces on plain gut.)

Some violinists prefer to use little rubber tubes or washers towards the end of the strings which rest on the bridge to protect the bridge and also to dampen the sound.

Acoustics

It has been known for a long time that the shape, or arching, as well as the thickness of the wood and its physical qualities govern the sound of a violin. The sound and tone of the violin is determined by how the belly and back plates of the violin behave acoustically, according to modes or schemes of movement determined by German physicist Ernst Chladni. Patterns of the nodes (places of no movement) made by sand or glitter sprinkled on the plates with the plate vibrated at certain frequencies are called "Chladni patterns", and are occasionally used by luthiers to verify their work before assembling the instrument. A scientific explanation includes a discussion of how the properties of the wood determine where the nodes occur, whether the plates move with end or diagonally opposite points rising together or in various mixed modes. This is why the most expensive violin in the world is of Stradivari Violins. Stradivari's lutherie visibly improves, as does his choice of wood. He incorporates an intense red, golden varnish into his instruments. Another important fact was the change in the arching of the top plate, meaning the instrument was less flexible, adding more resistance in the plate so the musician could play deeper sounds with this stronger core.[3]

Sizes

Children learning the violin often use "fractional-sized" violins: 3/4, 1/2, 1/4, 1/8, 1/10, 1/16, and sometimes even 1/32 sized instruments are used. These numbers do not represent numerically accurate size relationships, i.e., a "1/2 size" violin is not half the length of a full-sized violin.

The body length (not including the neck) of a 'full-size' or 4/4 violin is 356 mm (14.0 in) (or smaller in some models of the 17th century). A 3/4 violin is 335 mm (13.2 in), and a 1/2 size is 310 mm (12 in). Rarely, one finds a size referred to as 7/8 which is approximately 340 mm (13.5 in), sometimes called a "ladies' fiddle." Viola size is specified as body length rather than fractional sizes. A 'full-size' viola averages 400 mm (16 in), but may range as long as 450 or 500 mm (18 or 20 in). Such extremely long instruments may be humorously referred to as "chin cellos." Occasionally, a violin may be strung with viola strings in order to serve as a 350 mm (14 in) viola.

References

- ↑

Darnton, Michael (1990). "Violin Setups". In Olsen, Tim (ed.). The Big Red Book of American Lutherie. Vol. 3. Guild of American Luthiers (published 2004). p. 366. ISBN 0-9626447-5-7.

... the weight (of four big, heavy fine tuners) ... strangles the instrument.

- ↑ Mantel, Gerhard (1995). "Problems of Sound Production: How to Make a String Speak". Cello Technique: Principles and Forms of Movement. Indiana University Press. pp. 135–41. ISBN 978-0-253-21005-0.

- ↑ "The Truly Stradivarius: How to Identify the Violin | Mio Cannone Violini". 24 January 2022.

Bibliography

- Courtnall, Roy; Chris Johnson (1999). The Art of Violin Making. London: Robert Hale. ISBN 0-7090-5876-4.

- Weisshaar, Hans; Margaret Shipman (1988). Violin Restoration. Los Angeles: Weisshaar~Shipman. ISBN 0-9621861-0-4.

- Angeloni Domenico, Il Liutaio - Origine e costruzione del violino e degli strumenti ad arco moderni, legatura tela edit. fig., pp. XXVI-558 con 176 figure e 33 tavole, Milano, HOEPLI, 1923

- Simone F. Sacconi, The secrets of Stradivari, Libreria del Convegno in Cremona, Cremona, 1972 Simone Ferdinando Sacconi

External links

- Anatomy of a violin

- The violin making manual - The complete violin making guide with vectorized images and plans

- Violin Maker's Workbook compiled by apprentice to master luthier

- 3D Images of violins created using CT scanning technology

- Violinbridges - Online archive of bridges of the violin family

- Violin Making - virtual tour of a violin shop

- Wire-frame vibration mode animation (Click the "animation" button on Martin Schleske's home page.)

- The Luthier Helper - Specialized search engine looking only in violin and stringed instrument making, repair and restoration resources