In mathematics and computer science, an unrooted binary tree is an unrooted tree in which each vertex has either one or three neighbors.

Definitions

A free tree or unrooted tree is a connected undirected graph with no cycles. The vertices with one neighbor are the leaves of the tree, and the remaining vertices are the internal nodes of the tree. The degree of a vertex is its number of neighbors; in a tree with more than one node, the leaves are the vertices of degree one. An unrooted binary tree is a free tree in which all internal nodes have degree exactly three.

In some applications it may make sense to distinguish subtypes of unrooted binary trees: a planar embedding of the tree may be fixed by specifying a cyclic ordering for the edges at each vertex, making it into a plane tree. In computer science, binary trees are often rooted and ordered when they are used as data structures, but in the applications of unrooted binary trees in hierarchical clustering and evolutionary tree reconstruction, unordered trees are more common.[1]

Additionally, one may distinguish between trees in which all vertices have distinct labels, trees in which the leaves only are labeled, and trees in which the nodes are not labeled. In an unrooted binary tree with n leaves, there will be n − 2 internal nodes, so the labels may be taken from the set of integers from 1 to 2n − 1 when all nodes are to be labeled, or from the set of integers from 1 to n when only the leaves are to be labeled.[1]

Related structures

Rooted binary trees

An unrooted binary tree T may be transformed into a full rooted binary tree (that is, a rooted tree in which each non-leaf node has exactly two children) by choosing a root edge e of T, placing a new root node in the middle of e, and directing every edge of the resulting subdivided tree away from the root node. Conversely, any full rooted binary tree may be transformed into an unrooted binary tree by removing the root node, replacing the path between its two children by a single undirected edge, and suppressing the orientation of the remaining edges in the graph. For this reason, there are exactly 2n −3 times as many full rooted binary trees with n leaves as there are unrooted binary trees with n leaves.[1]

Hierarchical clustering

A hierarchical clustering of a collection of objects may be formalized as a maximal family of sets of the objects in which no two sets cross. That is, for every two sets S and T in the family, either S and T are disjoint or one is a subset of the other, and no more sets can be added to the family while preserving this property. If T is an unrooted binary tree, it defines a hierarchical clustering of its leaves: for each edge (u,v) in T there is a cluster consisting of the leaves that are closer to u than to v, and these sets together with the empty set and the set of all leaves form a maximal non-crossing family. Conversely, from any maximal non-crossing family of sets over a set of n elements, one can form a unique unrooted binary tree that has a node for each triple (A,B,C) of disjoint sets in the family that together cover all of the elements.[2]

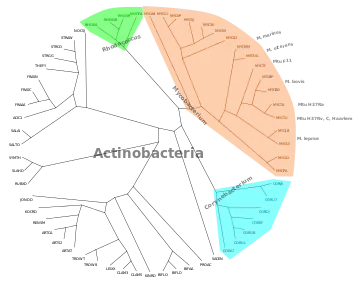

Evolutionary trees

According to simple forms of the theory of evolution, the history of life can be summarized as a phylogenetic tree in which each node describes a species, the leaves represent the species that exist today, and the edges represent ancestor-descendant relationships between species. This tree has a natural orientation from ancestors to descendants, and a root at the common ancestor of the species, so it is a rooted tree. However, some methods of reconstructing binary trees can reconstruct only the nodes and the edges of this tree, but not their orientations.

For instance, cladistic methods such as maximum parsimony use as data a set of binary attributes describing features of the species. These methods seek a tree with the given species as leaves in which the internal nodes are also labeled with features, and attempt to minimize the number of times some feature is present at only one of the two endpoints of an edge in the tree. Ideally, each feature should only have one edge for which this is the case. Changing the root of a tree does not change this number of edge differences, so methods based on parsimony are not capable of determining the location of the tree root and will produce an unrooted tree, often an unrooted binary tree.[3]

Unrooted binary trees also are produced by methods for inferring evolutionary trees based on quartet data specifying, for each four leaf species, the unrooted binary tree describing the evolution of those four species, and by methods that use quartet distance to measure the distance between trees.[4]

Branch-decomposition

Unrooted binary trees are also used to define branch-decompositions of graphs, by forming an unrooted binary tree whose leaves represent the edges of the given graph. That is, a branch-decomposition may be viewed as a hierarchical clustering of the edges of the graph. Branch-decompositions and an associated numerical quantity, branch-width, are closely related to treewidth and form the basis for efficient dynamic programming algorithms on graphs.[5]

Enumeration

Because of their applications in hierarchical clustering, the most natural graph enumeration problem on unrooted binary trees is to count the number of trees with n labeled leaves and unlabeled internal nodes. An unrooted binary tree on n labeled leaves can be formed by connecting the nth leaf to a new node in the middle of any of the edges of an unrooted binary tree on n − 1 labeled leaves. There are 2n − 5 edges at which the nth node can be attached; therefore, the number of trees on n leaves is larger than the number of trees on n − 1 leaves by a factor of 2n − 5. Thus, the number of trees on n labeled leaves is the double factorial

The numbers of trees on 2, 3, 4, 5, ... labeled leaves are

Fundamental Equalities

The leaf-to-leaf path-length on a fixed Unrooted Binary Tree (UBT) T encodes the number of edges belonging to the unique path in T connecting a given leaf to another leaf. For example, by referring to the UBT shown in the image on the right, the path-length between the leaves 1 and 2 is equal to 2 whereas the path-length between the leaves 1 and 3 is equal to 3. The path-length sequence from a given leaf on a fixed UBT T encodes the lengths of the paths from the given leaf to all the remaining ones. For example, by referring to the UBT shown in the image on the right, the path-length sequence from the leaf 1 is . The set of path-length sequences associated to the leaves of T is usually referred to as the path-length sequence collection of T [7] .

Daniele Catanzaro, Raffaele Pesenti and Laurence Wolsey showed[7] that the path-length sequence collection encoding a given UBT with n leaves must satisfy specific equalities, namely

- for all

- for all

- for all

- for all (which is an adaptation of the Kraft–McMillan inequality)

- , also referred to as the phylogenetic manifold.[7]

These equalities are proved to be necessary and independent for a path-length collection to encode an UBT with n leaves.[7] It is currently unknown whether they are also sufficient.

Alternative names

Unrooted binary trees have also been called free binary trees,[8] cubic trees,[9] ternary trees[5] and unrooted ternary trees,.[10] However, the "free binary tree" name has also been applied to unrooted trees that may have degree-two nodes[11] and to rooted binary trees with unordered children,[12] and the "ternary tree" name is more frequently used to mean a rooted tree with three children per node.

Notes

- 1 2 3 Furnas (1984).

- ↑ See e.g. Eppstein (2009) for the same correspondence between clusterings and trees, but using rooted binary trees instead of unrooted trees and therefore including an arbitrary choice of the root node.

- ↑ Hendy & Penny (1989).

- ↑ St. John et al. (2003).

- 1 2 Robertson & Seymour (1991).

- ↑ Balding, Bishop & Cannings (2007).

- 1 2 3 4 Catanzaro D, Pesenti R, Wolsey L (2020). "On the Balanced Minimum Evolution Polytope". Discrete Optimization. 36: 100570. doi:10.1016/j.disopt.2020.100570. S2CID 213389485.

- ↑ Czumaj & Gibbons (1996).

- ↑ Exoo (1996).

- ↑ Cilibrasi & Vitanyi (2006).

- ↑ Harary, Palmer & Robinson (1992).

- ↑ Przytycka & Larmore (1994).

References

- Balding, D. J.; Bishop, Martin J.; Cannings, Christopher (2007), Handbook of Statistical Genetics, vol. 1 (3rd ed.), Wiley-Interscience, p. 502, ISBN 978-0-470-05830-5.

- Cilibrasi, Rudi; Vitanyi, Paul M.B. (2006). "A new quartet tree heuristic for hierarchical clustering". arXiv:cs/0606048..

- Czumaj, Artur; Gibbons, Alan (1996), "Guthrie's problem: new equivalences and rapid reductions", Theoretical Computer Science, 154 (1): 3–22, doi:10.1016/0304-3975(95)00126-3.

- Eppstein, David (2009), "Squarepants in a tree: Sum of subtree clustering and hyperbolic pants decomposition", ACM Transactions on Algorithms, 5 (3): 1–24, arXiv:cs.CG/0604034, doi:10.1145/1541885.1541890, S2CID 2434.

- Exoo, Geoffrey (1996), "A simple method for constructing small cubic graphs of girths 14, 15, and 16" (PDF), Electronic Journal of Combinatorics, 3 (1): R30, doi:10.37236/1254.

- Furnas, George W. (1984), "The generation of random, binary unordered trees", Journal of Classification, 1 (1): 187–233, doi:10.1007/BF01890123, S2CID 121121529.

- Harary, Frank; Palmer, E.M.; Robinson, R.W. (1992), "Counting free binary trees admitting a given height" (PDF), Journal of Combinatorics, Information, and System Sciences, 17: 175–181.

- Hendy, Michael D.; Penny, David (1989), "A framework for the quantitative study of evolutionary trees", Systematic Biology, 38 (4): 297–309, doi:10.2307/2992396, JSTOR 2992396

- Przytycka, Teresa M.; Larmore, Lawrence L. (1994), "The optimal alphabetic tree problem revisited", Proc. 21st International Colloquium on Automata, Languages and Programming (ICALP '94), Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol. 820, Springer-Verlag, pp. 251–262, doi:10.1007/3-540-58201-0_73.

- Robertson, Neil; Seymour, Paul D. (1991), "Graph minors. X. Obstructions to tree-decomposition", Journal of Combinatorial Theory, 52 (2): 153–190, doi:10.1016/0095-8956(91)90061-N.

- St. John, Katherine; Warnow, Tandy; Moret, Bernard M. E.; Vawterd, Lisa (2003), "Performance study of phylogenetic methods: (unweighted) quartet methods and neighbor-joining" (PDF), Journal of Algorithms, 48 (1): 173–193, doi:10.1016/S0196-6774(03)00049-X, S2CID 5550338.