_1912.jpg.webp) Alabama off New York City in 1912 | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Alabama |

| Namesake | State of Alabama |

| Builder | William Cramp & Sons, Philadelphia |

| Yard number | 290 |

| Laid down | 1 December 1896 |

| Launched | 18 May 1898 |

| Commissioned | 16 October 1900 |

| Decommissioned | 7 May 1920 |

| Stricken | Transferred to War Department, 15 September 1921 |

| Fate |

|

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type | Illinois-class battleship |

| Displacement | |

| Length | 374 ft (114 m) loa |

| Beam | 72 ft 3 in (22.02 m) |

| Draft | 23 ft 6 in (7.16 m) |

| Installed power |

|

| Propulsion |

|

| Speed | 16 knots (30 km/h; 18 mph) |

| Crew | 536 |

| Armament |

|

| Armor |

|

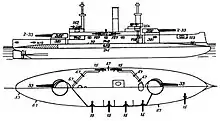

USS Alabama (BB-8) was an Illinois-class pre-dreadnought battleship built for the United States Navy. She was the second ship of her class, and the second to carry her name. Her keel was laid down in December 1896 at the William Cramp & Sons shipyard, and she was launched in May 1898. She was commissioned into the fleet in October 1900. The ship was armed with a main battery of four 13-inch (330 mm) guns and she had a top speed of 16 knots (30 km/h; 18 mph).

Alabama spent the first seven years of her career in the North Atlantic Fleet conducting peacetime training. In 1904, she made a visit to Europe and toured the Mediterranean. She took part in the cruise of the Great White Fleet until damage to her machinery forced her to leave the cruise in San Francisco. She instead completed a shorter circumnavigation in company with the battleship Maine. The ship received an extensive modernization from 1909 to 1912, after which she was used as a training ship in the Atlantic Reserve Fleet. She continued in this role during World War I. After the war, Alabama was stricken from the naval register and allocated to bombing tests that were conducted in September 1921. She was sunk in the tests by US Army Air Service bombers and later sold for scrap in March 1924.

Description

Design work on the Illinois class of pre-dreadnought battleships began in 1896, at which time the United States Navy had few modern battleships in service. Initial debate over whether to build a new low-freeboard design like the Indiana-class battleships in service or a higher-freeboard vessel like Iowa (then under construction) led to a decision to adopt the latter type. The mixed secondary armament of 6 and 8 in (152 and 203 mm) guns of previous classes was standardized to just 6-inch weapons to save weight and simplify ammunition supplies. Another major change was the introduction of modern, balanced turrets with sloped faces instead of the older "Monitor"-style turrets of earlier American battleships.[1]

Alabama was 374 feet (114 m) long overall and had a beam of 72 ft 3 in (22.02 m) and a draft of 23 ft 6 in (7.16 m). She displaced 11,565 long tons (11,751 t) as designed and up to 12,250 long tons (12,450 t) at full load. The ship was powered by two-shaft triple-expansion steam engines rated at 16,000 indicated horsepower (12,000 kW), driving two screw propellers. Steam was provided by eight coal-fired fire-tube boilers, which were ducted into a pair of funnels placed side by side. The propulsion system generated a top speed of 16 knots (30 km/h; 18 mph). As built, she was fitted with heavy military masts, but these were replaced by cage masts in 1909. She had a crew of 536 officers and enlisted men, which increased to 690–713.[2]

The ship was armed with a main battery of four 13 in (330 mm)/35 caliber guns[lower-alpha 1] in two twin-gun turrets on the centerline, one forward and aft. The secondary battery consisted of fourteen 6 in (152 mm)/40 caliber Mark IV guns, which were placed in casemates in the hull. For close-range defense against torpedo boats, she carried sixteen 6-pounder guns mounted in casemates along the side of the hull and six 1-pounder guns. As was standard for capital ships of the period, Alabama carried four 18 in (457 mm) torpedo tubes in deck mounted launchers.[2]

Alabama's main armored belt was 16.5 in (419 mm) thick over the magazines and the propulsion machinery spaces and 4 in (102 mm) elsewhere. The main battery gun turrets had 14-inch (356 mm) thick faces, and the supporting barbettes had 15 in (381 mm) of armor plating on their exposed sides. Armor that was 6 in thick protected the secondary battery. The conning tower had 10 in (254 mm) thick sides.[2]

Service history

Construction – 1911

_1904.jpg.webp)

Alabama was laid down at the William Cramp & Sons shipyard in Philadelphia on 2 December 1896 and was launched on 18 May 1898. She was commissioned on 16 October 1900, the first member of her class to enter service.[2] The ship's first commander was Captain Willard H. Brownson. Alabama was assigned to the North Atlantic Squadron, though she remained at Philadelphia until 13 December, when she made a visit to New York, where she remained through January 1901. On the 27th, Alabama steamed south for the Gulf of Mexico, where she joined the rest of the North Atlantic Squadron for training exercises off Pensacola, Florida.[3] In August 1901, while the North Atlantic Squadron conducted target practice off of Nantucket Island, Alabama experienced an outbreak of mumps and was placed in quarantine, unable to participate.[4]

For the next six years, she followed a pattern of fleet training in the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean during the winter, followed by repairs and then operations off the east coast of the United States from the middle of the year onward. The only interruption came in 1904, when she, the battleships Kearsarge, Maine, and Iowa, and the protected cruisers Olympia, Baltimore, and Cleveland made a visit to southern Europe. During the trip, they stopped in Lisbon, Portugal, before touring the Mediterranean until mid-August. They then recrossed the Atlantic, stopping in the Azores while en route, and arrived in Newport, Rhode Island on 29 August. Toward the end of September, Alabama went into dry dock at the League Island Navy Yard for repairs, which were completed by early December.[3] On 31 July 1906, the ship was involved in a collision with her sister Illinois.[5]

Alabama's next significant action was the cruise of the Great White Fleet around the world, which started with a naval review for President Theodore Roosevelt in Hampton Roads.[3] The cruise of the Great White Fleet was conceived as a way to demonstrate American military power, particularly to Japan. Tensions had begun to rise between the United States and Japan after the latter's victory in the Russo-Japanese War in 1905, particularly over racist opposition to Japanese immigration to the United States. The press in both countries began to call for war, and Roosevelt hoped to use the demonstration of naval might to deter Japanese aggression.[6]

On 17 December, the fleet steamed out of Hampton Roads and cruised south to the Caribbean and then to South America, making stops in Port of Spain, Rio de Janeiro, Punta Arenas, and Valparaíso, among other cities. After arriving in Mexico in March 1908, the fleet spent three weeks conducting gunnery practice.[7] The fleet then resumed its voyage up the Pacific coast of the Americas, stopping in San Francisco, where Alabama was detached from the rest of the fleet. The ship could not keep up with the fleet due to a cracked cylinder head, which necessitated repairs at the Mare Island Navy Yard. The battleship Maine also left the fleet, as her boilers had proved to be badly inefficient, requiring excessive amounts of coal.[8]

On 8 June, Alabama and Maine began their crossing of the Pacific independently, via Honolulu, Hawaii, Guam, and Manila in the Philippines. They then cruised south to Singapore in August and crossed the Indian Ocean, stopping in Colombo, Ceylon, and Aden on the Arabian peninsula on the way. The ships then steamed through the Mediterranean, stopping only in Naples, Italy, before calling at Gibraltar and then proceeding across the Atlantic in early October. They stopped in the Azores before arriving off the east coast of the United States on 19 October; the two ships then parted company, with Alabama steaming to New York, while Maine went to Portsmouth, New Hampshire. Both ships arrived the following day. Following her arrival, Alabama was reduced to reserve status on 3 November. She remained in New York, and on 17 August 1909, she was decommissioned for a major overhaul that lasted until early 1912.[3]

1912–1919

Alabama returned to service on 17 April 1912 in the Atlantic Reserve Fleet, under Commander Charles F. Preston. The ships of the Atlantic Reserve Fleet—which included eight other battleships and three cruisers—were kept in service with reduced crews that could be fleshed out with naval militiamen and volunteers in the event of an emergency. There were enough officers and men in the Atlantic Reserve Fleet to fully man two or three ships, which allowed them to take them to sea in rotating groups to ensure that the ships were in good condition. On 25 July, Alabama was temporarily placed in full commission for service with the Atlantic Fleet during the summer training exercises, before returning to reserve status on 10 September. In mid-1913, the Navy began to use the Atlantic Reserve Fleet to train naval militia units. Alabama operated off the east coast of the United States and made two training cruises to Bermuda that summer to train men from the naval militias of several states. These operations ended on 2 September, and on 31 October she was again laid up.[3]

The ship remained largely inactive in Philadelphia for the next three years. On 22 January 1917, she became a receiving ship for naval recruits. Alabama was transferred to the southern Chesapeake to begin training recruits in the middle of March. Shortly thereafter, on 6 April, the United States declared war on Germany. Two days later, Alabama became the flagship of the 1st Division, Atlantic Fleet, and for the rest of the war she continued her training mission of the east coast of the United States. During this period, she made one cruise to the Gulf of Mexico from late June to early July 1918. On 11 November, Germany signed the Armistice that ended the fighting in Europe; Alabama continued training naval recruits, though at a reduced level of intensity. She took part in fleet maneuvers in February and March 1919 in the West Indies before returning to Philadelphia in April for repairs. A summer training cruise for midshipmen from the US Naval Academy followed; Alabama departed Philadelphia on 28 May bound for Annapolis, where she arrived the next day. After taking on a contingent of 184 midshipmen, she steamed out of Annapolis on 9 June. The cruise went to the West Indies and passed through the Panama Canal and back. By mid-July, the ship was cruising off the coast of New England. She returned south in August for maneuvers, and at the end of the month she returned the midshipmen to Annapolis before docking in Philadelphia.[3]

Bombing tests

_-_NH_924.jpg.webp)

Alabama was decommissioned for the final time on 7 May 1920, having spent the previous nine months inactive at Philadelphia. The ship was transferred to the War Department for use as a target ship on 15 September 1921, and she was stricken from the naval register. She was allocated to bombing tests conducted by the US Army Air Service on 27 September 1921, under the supervision of General Billy Mitchell. In addition to Alabama, the old battleships New Jersey and Virginia were to be sunk in the tests.[3][9] The first phase of the testing began on 23 September, and included tests with chemical bombs, including tear gas and white phosphorus, to demonstrate how such weapons could be used to disable command and control systems and kill exposed personnel. That night, another test with 300 lb (136 kg) demolition bombs took place, the purpose of which was to determine whether flares could sufficiently illuminate a target for precise bombing.[10] The second phase took place the next morning, and it was a much larger operation. The 1st Provisional Air Brigade took part in the tests, which were to simulate a combat scenario. A group of eight Royal Aircraft Factory S.E.5s, armed with 25 lb (11 kg) bombs attacked first; their bombs and machine gun fire were intended to simulate clearing the decks of anti-aircraft gunners in preparation for the heavy bombers. Four Martin NBS-1 bombers attacked next, with 300 lb (136 kg) bombs at an altitude of 1500 ft (457 m). Two of the bombs hit the deck toward the bow. Three more NBS-1s followed with 1100 lb (499 kg) armor-piercing bombs, though none of these hit.[11]

On 25 September 1921, the last round of tests took place. Seven more NBS-1s attacked the ship; three carried 1,100 lb (499 kg) bombs, while the other four carried one 2,000 lb (910 kg) bomb each. One of the 2,000 lb (907 kg) bombs landed close to the ship on the port side; the mining effect caused considerable damage,[lower-alpha 2] and Alabama began listing to port. The bombers scored two more near-misses with the 2,000 lb (907 kg) bombs, followed by a direct hit and two near misses with the 1,100 lb (499 kg) bombs. The last bomb, a 2,000 lb (907 kg) weapon, struck the ship at her stern. The blast broke her anchor chains, and the battered ship began to drift toward the wrecks of San Marcos and Indiana, the latter having been sunk in bombing tests earlier that year.[12] The ship remained afloat for another two days before finally sinking in shallow water on 27 September 1921.[3] Mitchell attempted to use the sinking as evidence of the predominance of the bomber in his efforts to secure an independent air force, though the Navy pointed out that the ship was stationary, undefended, unmanned, and was not protected with the latest "all or nothing" armor scheme.[12] The sunken wreck was sold for scrap on 19 March 1924.[3]

Footnotes

Notes

- ↑ /35 refers to the length of the gun in terms of calibers. A /35 gun is 35 times long as it is in bore diameter.

- ↑ Bombs that explode underwater are identical in effect to naval mines; the damage to a ship inflicted derives from the relative incompressibility of water, which transmits the force of the blast directly to the hull.[12]

Citations

References

- "Alabama II (Battleship No. 8)". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Naval History & Heritage Command. 9 November 2004. Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- Albertson, Mark (2007). U.S.S. Connecticut: Constitution State Battleship. Mustang: Tate Publishing. ISBN 978-1-59886-739-8.

- Campbell, N. J. M. (1979). "United States of America". In Chesneau, Roger & Kolesnik, Eugene M. (eds.). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1860–1905. Greenwich: Conway Maritime Press. pp. 114–169. ISBN 978-0-85177-133-5.

- Friedman, Norman (1985). U.S. Battleships: An Illustrated Design History. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-715-9.

- Hendrix, Henry (2009). Theodore Roosevelt's Naval Diplomacy: The U.S. Navy and the Birth of the American Century. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-61251-831-2.

- "Mumps on the Alabama". The Boston Globe. 11 August 1901. p. 3 – via Newspapers.com.

- Silverstone, Paul H. (2013). The New Navy, 1883–1922. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-97871-2.

- Wildenberg, Thomas (2014). Billy Mitchell's War with the Navy: The Army Air Corps and the Challenge to Seapower. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-61251-332-4.

Further reading

- Alden, John D. (1989). American Steel Navy: A Photographic History of the U.S. Navy from the Introduction of the Steel Hull in 1883 to the Cruise of the Great White Fleet. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-248-2.

- Reilly, John C.; Scheina, Robert L. (1980). American Battleships 1886–1923: Predreadnought Design and Construction. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-524-7.

External links

![]() Media related to USS Alabama (BB-8) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to USS Alabama (BB-8) at Wikimedia Commons

- Photo gallery of Alabama at NavSource Naval History