42°30′N 45°30′E / 42.500°N 45.500°E

Tusheti

თუშეთი | |

|---|---|

Keselo | |

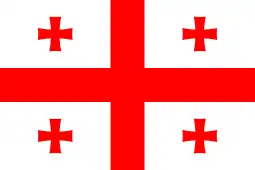

Map highlighting the historical region of Tusheti in Georgia | |

| Country | |

| Mkhare | Kakheti |

| Capital | Omalo |

| Area | |

| • Total | 969 km2 (374 sq mi) |

Tusheti (Georgian: თუშეთი, romanized: tusheti; Bats: Баца, romanized: Batsa)[1] is a historic region in northeast Georgia. A mountainous area, it is home to the Tusheti National Park

Geography

Located on the northern slopes of the Greater Caucasus Mountains, Tusheti is bordered by the Russian republics of Chechnya and Dagestan to the north and east, respectively; and by the Georgian historic provinces Kakheti and Pshav-Khevsureti to the south and west, respectively.[2] The population of the area is mainly ethnic Georgians called Tushs or Tushetians (Georgian: tushebi).

Historically, Tusheti comprised four mountain communities: the Tsova (living in the Tsova Gorge), the Gometsari (living along the banks of the Tushetis Alazani River), the Pirikiti (living along the banks of the Pirikitis Alazani River), and the Chaghma (living close to the confluence of the two rivers). Administratively speaking, Tusheti is now part of the raioni of Akhmeta, itself part of Georgia's eastern region of Kakheti. The largest village in Tusheti is Omalo.

History

The area is thought to have long been inhabited by the Tush, a subgroup of Georgians, which themselves divide into two groups- the Chaghma-Tush (Georgian name, used for Tush who speak the local Georgian dialect) and Tsova-Tush (Nakh-speaking Tush, better known as Bats or Batsbi). There are three major theories on the origins of the Bats (with various variations).

Ants Viires notes that there are theories involving the Bats being descended from Old Georgian tribes who adopted a Nakh language. According to this theory, the Batsbi are held to have originated from Georgian pagan tribes who fled the Christianization being implemented by the Georgian monarchy. A couple of these tribes are thought to have adopted a Nakh language as a result of contact with Nakh peoples.

Another theory is that the Bats are the remnant of a larger Nakh-speaking people. Jaimoukha speculates that they may be descended from the Kakh, a historical people living in Kakheti and Tusheti (who apparently called themselves Kabatsa).[3] However, the belief that the Kakh were originally Nakh is not widely held. The Georgian name for the Bats, the Tsova-Tush, may also (or instead) be linked to the Tsov, a historical Nakh people claimed by the Georgian historian Melikishvilli to have ruled over the Kingdom of Sophene in Urartu (called Tsobena in Georgian) who were apparently forcefully moved to the region around Erebuni, a region linked to Nakh peoples by place names and various historiography.[4][5][6] However, theories linking the Bats to Transcaucasian peoples are not universally accepted (see below).

The third theory has it that the Batsbi crossed the Greater Caucasus range from Ingusheti in the seventeenth century and eventually settled in Tusheti,[7][8] and that they are therefore a tribe of Ingush origin which was Christianized and "Georgianized" over the centuries.

King Levan of Kakheti (1520–1574) apparently granted the Bats official ownership of the lands in the Alvani Valley in exchange for their military service. Bats-speaking inhabitants of Tusheti are known to the local Georgians as the Tsova-Tushs, they are typically bilingual using both Georgian and their own Bats languages. Nowadays, Bats is spoken only in a village Zemo Alvani. Anthropological studies on the Tsova-Tush found them to be somewhere in between the Chechen-origin Kists and the Chaghma-Tush of the region, but significantly closer to the Chaghma-Tush.[9]

The Bats have considered themselves Georgian by nation for a long period of time, and have been speaking Georgian for a while as well.[10] They are Georgian Orthodox Christians.

Pagan Georgians from Pkhovi took refuge in the uninhabited mountains during their rebellion against Christianization implemented by the Iberian king Mirian III in the 330s.

Regarding the relationship between the Nakh (Tsova) and Georgian (Chaghma) Tushians, the "Red Book", states the following:

For centuries there have been two communities next to each other in Tusheti, one speaking the Nakh language, the other Old Georgian. The general name for them is tush, according to their language either Tsova- or Chagma-Tushian. They formed one single material and intellectual unit with Old Georgian elements prevailing.

The descendants of the Old Georgian pagan tribes, whose ancestors had fled from Christianity to Tusheti, are regarded as Tushians. In the mountains some of the fugitives splintered off from other Old Georgian tribes. They were in close contact with the Nakh tribes which resulted in a new linguistic unit.[9]

After the collapse of the unified Georgian monarchy, Tusheti came under the rule of Kakhetian kings in the fifteenth century.

Many Tush families began to move southwards from Tusheti during the first half of the nineteenth century and settled in the low-lying fields of Alvan at the western end of Kakheti.

.jpg.webp)

(Alvan had already belonged to the Tush as a wintering-ground for their flocks for centuries; it was bequeathed to them in the seventeenth century in recognition of their valuable assistance in defeating a Safavid army at the Battle of Bakhtrioni in 1659: Like a rushing stream did the Toushines make their way into the fortress, while the first rays of the rising sun were falling upon the grim old fortifications. The Tartars, half asleep, ran out into a field, but in vain for now they were met by the Pchaves and Khevsoures, who had ventured out from the gorge of Pankisse. The Tartars, surrounded on all sides, were exterminated to the last.[11])

The first to move were the Bats people following the destruction of one of their most important villages by a landslide in c.1830 and an outbreak of the plague.[12] The Tush of the Chaghma, Pirikiti and Gometsari communities followed later. Many of these families practiced a semi-nomadic way of life, the men spending the summer with the flocks of sheep high up in the mountains between April and October, and wintering their flocks in Kakheti.

During the German invasion of the Soviet Union, a minor anti-Soviet revolt took place in the area in 1942-1943, seemingly linked to the similar but more large-scale events in the neighbouring Ingushetia.

Culture

Traditionally, the Tushs are sheep herders. Tushetian Guda cheese and high quality wool was famous and was exported to Europe and Russia. Even today sheep and cattle breeding is the leading branch of the economy of highland Tusheti. The local shepherds spend the summer months in the highland areas of Tusheti but live in the lowland villages of Zemo Alvani and Kvemo Alvani in wintertime.[13] Their customs and traditions are similar to those of other eastern Georgian mountaineers (see Khevsureti).

One of the most ecologically unspoiled regions in the Caucasus, Tusheti is a popular mountain trekking venue.

Pork is considered taboo and bringing a bad luck in Tusheti.[14] Farmers will not raise pigs and travelers are usually advised to not bring any pork into the region. Locals will however eat pork themselves when not in Tusheti. But, some families will also shun pork even when they are in the valley outside the region.[14]

Historical population figures

Figures from the Russian imperial census of 1873 given in Dr. Gustav Radde's Die Chews'uren und ihr Land — ein monographischer Versuch untersucht im Sommer 1876 (published by Cassel in 1878) divide the villages of Tusheti into eight communities:[15]

- the Parsma community: 7 villages, 133 households, consisting of 290 men and 260 women, totalling 550 souls

- the Dartlo community: 6 villages, 143 households, consisting of 251 men and 275 women, totalling 526 souls

- the Omalo community: 7 villages, 143 households, consisting of 354 men and 362 women, totalling 716 souls

- the Natsikhvári community: 8 villages, 116 households, consisting of 282 men and 293 women, totalling 575 souls

- the Djvar-Boseli community: 10 villages, 116 households, consisting of 270 men and 295 women, totalling 565 souls

- the Indurta community: 1 village, 191 households, consisting of 413 men and 396 women, totalling 809 souls

- the Sagirta community: 3 villages, 153 households, consisting of 372 men and 345 women, totalling 717 souls

- the Iliúrta community: 8 villages, 136 households, consisting of 316 men and 329 women, totalling 645 souls

1873 TOTAL: 50 villages, 1,131 households, consisting of 2,548 men and 2,555 women, in all 5,103 souls.

Note: The Indurta and Sagirta communities were home to the Bats people.

See also

External links

- Tusheti National Park - official website

- Peter Nasmyth (2006), Walking in the Caucasus - Georgia: A Complete Guide to the Birds, Flora and Fauna of Europe's, page 121-140, ISBN 1-84511-206-7

- The Bats people

- Photos of Tusheti

References

- ↑ Старчевскій 1891, p. 158.

- ↑ "Georgia". www.gotocaucasus.com. Retrieved 2017-07-28.

- ↑ Jaimoukha, Amjad. The Chechens: A Handbook. Routledge Curzon: Oxon, 2005. Page 29

- ↑ Джавахишвили И. А. Введение в историю грузинского народа. кн.1, Тбилиси, 1950, page.47-49

- ↑ Ахмадов, Шарпудин Бачуевич (2002). Чечня и Ингушетия в XVIII - начале XIX века. Elista: "Джангар", АПП. p. 52.

- ↑ Гаджиева В. Г. Сочинение И. Гербера Описание стран и народов между Астраханью и рекою Курой находящихся, М, 1979, page.55.

- ↑ NICHOLS, Johanna, "The Origin of the Chechen and Ingush: A Study in Alpine Linguistic and Ethnic Geography", Anthropological Linguistics, Vol. 46, No. 2, 2004.

- ↑ 15 and 20(c) in ALLEN, W.E.D. (Ed.), Russian Embassies to the Georgian Kings – 1589–1605, The Hakluyt Society, Second Series No. CXXXVIII, Cambridge University Press, 1970

- 1 2 The Red Book of Peoples of the Russian Empire; Bats section. Available online: http://www.eki.ee/books/redbook/bats.shtml

- ↑ Johanna Nichols, ibid.

- ↑ GOULBAT, A., "The Tale of Zesva", in Caucasian Legends, translated from the Russian of A. Goulbat by Sergei de Wesselitsky-Bojidarovitch, New York: Hinds, Noble and Eldredge, 1904

- ↑ TOPCHISHVILI, Prof. Roland, The Tsova-Tushs (the Batsbs), article published with funding from the University of Frankfurt's ECLING project

- ↑ Mühlfried, Florian (2014). Being a State and States of Being in Highland Georgia. New York: Berghahn. ISBN 978-1-78238-296-6.

- 1 2 Gogua, Giorgi (27 May 2021). "A rare look at a perilous journey in the Caucasus Mountains". National Geographic. Archived from the original on May 27, 2021. Retrieved 12 November 2022.

- ↑ For detailed tables, go to this page on Batsav.com

Bibliography

- Старчевскій, А. В. (1891). Кавказскій Толмачъ [Caucasian Translator] (in Russian). СПб: Типографія И. Н. Скороходова. pp. 1–690.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link)