Thomas Thomson MD FRS FLS FRSE (12 April 1773 – 2 August 1852) was a Scottish chemist and mineralogist whose writings contributed to the early spread of Dalton's atomic theory. His scientific accomplishments include the invention of the saccharometer[1] and he gave silicon its current name. He served as president of the Philosophical Society of Glasgow.

Thomson was the father of the botanist Thomas Thomson, and the uncle and father-in-law of the Medical Officer of Health Robert Thomson.

Life and work

Thomas Thomson was born in Crieff in Perthshire, on 12 April 1773 the son of Elizabeth Ewan and John Thomson.

He was educated at Crieff Parish School and Stirling Burgh School. He then studied for a general degree at the University of St Andrews to study in classics, mathematics, and natural philosophy from 1787 to 1790. He had a five year break then entered University of Edinburgh to study medicine in 1795, gaining his doctorate (MD) in 1799. During this latter period he was inspired by his tutor, Professor Joseph Black, to take up the study of chemistry.

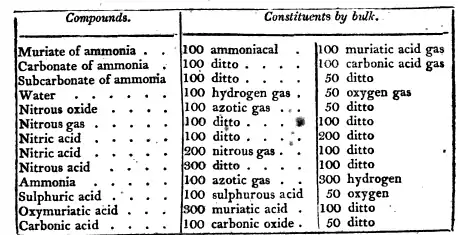

In 1796, Thomson succeeded his brother, James, as assistant editor of the Supplement to the Third Edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica (1801), contributing the articles Chemistry, Mineralogy, and Vegetable, animal and dyeing substances. The Mineralogy article contained the first use of letters as chemical symbols.[2] In 1802, Thomson used these articles as the basis of his book System of Chemistry. His book Elements of Chemistry, published in 1810, displayed how volumes of different gasses react in a way that is supported by the atomic theory.

In 1802 he began teaching Chemistry in Edinburgh. In 1805 he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. His proposers were Robert Jameson, William Wright, and Thomas Charles Hope.[3]

Thomson dabbled in publishing, acted as a consultant to the Scottish excise board, invented the instrument known as Allan's saccharometer, and opposed the geological theories of James Hutton, founding the Wernerian Natural History Society of Edinburgh as a platform in 1808. In March 1811, he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society[4] and in 1815 was elected a corresponding member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences. In 1813 he founded Annals of Philosophy a leader in its field of commercial scientific periodicals.[5]

In 1817, he gave silicon its present name, rejecting the suggested "silicium" because he felt the element had no metallic characteristics, and that it chemically bore a close resemblance to boron and carbon.[6]

In 1817, Thomson became lecturer in and subsequently Regius Professor of Chemistry at the University of Glasgow, retiring in 1841. In 1820, he identified a new zeolite mineral, named thomsonite in his honour.

He lived his final years at 8 Brandon Place in Glasgow.[7] He died at Kilmun in Argyllshire in 1852, aged 79. There is a memorial for him at the Glasgow Necropolis.[8]

Family

In 1816, he married Agnes Colquhoun.

He was uncle and father-in-law to Robert Dundas Thomson.

Honours

- Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh (1805)

- Fellow of the Royal Society, (1811)

Artistic Recognition

He was portrayed by John Graham Gilbert.[9]

Selected writings

- System of Chemistry (1802)

- The Elements of Chemistry (1810)

- History of the Royal Society, from its institution to the end of the eighteenth century (1812)

- An Attempt to Establish the First Principles of Chemistry by Experiment (1825)

- History of Chemistry (1830)

- A System of Chemistry of Inorganic Bodies (1831)

- Chemistry of Animal Bodies (1843)

- Outlines of Mineralogy and Geology (1836)

- Chemistry (article in 7th edition of Encyclopedia Britannia) (1842)

From 1813 to 1822 he was Editor of the Annals of Philosophy.

In culture

In June 2011, Russian artist Alexander Taratynov installed a life-size statue of French architect Thomas de Thomon (1760–1813) in Saint Petersburg. The statue is part of The Architects, a bronze sculptural group depicting the great architects of Russian Empire as commissioned by Gazprom and installed in Alexander Park. In 2018 associate of Shchusev Museum of Architecture Kirill Posternak discovered a mistake. Taratynov admitted he used a picture he found on Wikipedia to base the statue on, and that it was actually an image of the Scottish chemist Thomas Thomson – he blamed Wikipedia for the error but also himself for not checking with a historian to verify it was accurate.[10][11]

Notes

- ↑ Biographical Index of Former Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh 1783–2002 (PDF). The Royal Society of Edinburgh. July 2006. ISBN 0-902-198-84-X. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 14 December 2018.

- ↑ "chemical symbol". Britannica. Retrieved 27 August 2023.

- ↑ Biographical Index of Former Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh 1783–2002 (PDF). The Royal Society of Edinburgh. July 2006. ISBN 0-902-198-84-X. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 14 December 2018.

- ↑ "Library and Archive Catalogue". Royal Society. Retrieved 25 October 2010.

- ↑ Morrell, Jack. "Thomson, Thomas". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/27325. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ Thomas Thomson, A System of Chemistry in Four Volumes, 5th ed. (London, England: Baldwin, Cradock, and Joy, 1817), vol. 1. From page 252: "The base of silica has been usually considered as a metal, and called silicium. But as there is not the smallest evidence for its metallic nature, and as it bears a close resemblance to boron and carbon, it is better to class it along with these bodies, and to give it the name of silicon."

- ↑ Glasgow Post Office Directory 1852

- ↑ Biographical Index of Former Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh 1783–2002 (PDF). The Royal Society of Edinburgh. July 2006. ISBN 0-902-198-84-X. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 14 December 2018.

- ↑ Illustrated Catalogue of the Exhibition of Portraits in the New Galleries of Art in Corporation Buildings

- ↑ Jack Aitchison (20 August 2018). "Wikipedia gaffe sees statue to Glasgow professor erected in RUSSIA". Daily Record. Retrieved 19 August 2018.

- ↑ Ilya Kazakov (16 August 2018). "Как Алексей Миллер подарил Петербургу вместо русского зодчего шотландского химика из Википедии" [As Alexey Miller presented to St. Petersburg instead of Russian architect Scottish chemist from Wikipedia]. Fontanka (in Russian). Archived from the original on 20 August 2018. Retrieved 19 August 2018.

The architect acknowledged the error and dumped the blame on Wikipedia, from which he downloaded the photo.

References

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Thomson, Thomas". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 26 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Further reading

- "Biographical notice of the late Thomas Thomson". Glasgow Medical Journal. 5: 69–80, 121–153. 1857.

- Crum, W. (1855). "Sketch of the life and labours of Dr Thomas Thomson". Proceedings of the Philosophical Society of Glasgow. 3: 250–264.

- Thomson, R.D. (1852–1853). "Memoir of the late Dr Thomas Thomson". Edinburgh New Philosophical Journal. 54: 86–98.

- Foundations of the atomic theory: comprising papers and extracts by John Dalton, William Hyde Wollaston, M. D., and Thomas Thomson, M. D. (1802–1808). Edinburgh: The Alembic Club. 1911.

External links

- . Dictionary of National Biography. 1885–1900.

- "Thomas Thomson". Archived from the original on 12 October 2008. Retrieved 8 September 2008.

- "Significant Scots". Retrieved 8 September 2008.

- Works by Thomas Thomson at Project Gutenberg

- Works by Thomas Thomson at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)