Thomas Fairchild | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 1667 |

| Died | 10 October 1729 |

| Nationality | British |

| Occupation | gardener |

Thomas Fairchild (? 1667 – 10 October 1729) was an English gardener, "the leading nurseryman of his day", working in London. He corresponded with Carl Linnæus, and helped by experiments to establish the existence of sex in plants, then still denied by most botanists.[1] In 1716-17 he was the first person to scientifically produce an artificial hybrid, Dianthus Caryophyllus barbatus, known as "Fairchild's Mule", a cross between a Sweet William (Dianthus barbatus) and a Carnation (Dianthus caryophyllus).[2] He did this by taking pollen from the Sweet William with a feather, and brushing it onto the stigma of the Carnation pink. The cross was made in summer 1716, the new plant appearing the next spring.

Fairchild was somewhat disturbed by his success, as like others at the time, he regarded all plant species as created by God at the Creation, and feared the consequences of disturbing this natural order. When asked to show his dried plant to the Royal Society in 1720, he fudged the story of its creation, claiming it was an accident.[3]

He introduced Pavia rubra or red buckeye, Cornus florida, an American flowering dogwood, and other plants.[4] He imported some plants from the Dutch growers, but was an early participant in the wave of introductions from the eastern seaboard of British America. Eventually he "could boast that more than twenty species blossomed in his garden each December", then regarded as remarkable for England.[5]

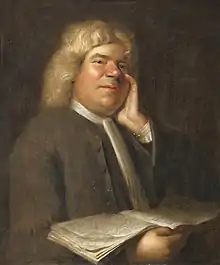

As a leading member of the community of scienticially-minded gardeners that was forming in London, he wrote The City Gardener (1722), contributed to A Catalogue of Trees and Shrubs both Exotic and Domestic which are propagated for Sale in the Gardens near London, and may have written the anonymous A Treatise on the Manner of Fallowing Ground, Raising of Grass Seeds, and Training Lint and Hemp. He also read a paper to the Royal Society.[4] He was sufficiently well known that his portrait by an unknown artist has been owned by what is now the Department of Plant Sciences, University of Oxford since the 18th century.[6]

Life

Fairchild established himself about 1690 as a nurseryman and florist at Hoxton, Shoreditch, London,, where his nursery was only half an acre,[7] but close to the City of London. Richard Bradley[8] mentions the variety of his fruits; Richard Pulteney classed him with Thomas Knowlton, Gordon, and Miller, as one of the leading gardeners of his time.

Fairchild died on 10 October 1729. He had taken up the freedom of the Clothworkers' Company in 1704, and in his will he is described as citizen and clothworker. In accordance with his direction he was buried in a church yard belonging to the parish of St. Leonard, Shoreditch; on his monument he was said to have died in his sixty-third year. He left the bulk of his property to his nephew, John Bacon of Hoxton, who was a member of the Society of Gardeners, and died on 20 February 1737, aged 25.[4] He also bequeathed £25 for an annual sermon on "the wonderfull works of God in the Creation", which is still delivered, now at St Giles, Cripplegate, attended by the Worshipful Company of Gardeners.[9]

Works

In 1722 he published the small book The City Gardener, devoted to a description of the trees, plants, shrubs, and flowers which would thrive best in London. Pear trees still bore excellent fruit about Barbican, Aldersgate, and Bishopsgate, that in 'Leicester Fields' there was a vine producing good grapes every year, and that figs and mulberries throve very well in the city. The highest whitethorn in England, Fairchild wrote, was growing in an alley leading from Whitecross Street towards Bunhill Fields.[4]

In 1724 Fairchild added to his reputation by a paper read before the Royal Society and afterwards printed in Philosophical Transactions (xxxiii. 127) on 'Some new Experiments relating to the different and sometimes contrary Motion of the Sap in Plants and Trees.' Besides these publications and letters which appeared in Bradley's works, George William Johnson, in his History of English Gardening (1829), ascribed to him A Treatise on the Manner of Fallowing Ground, Raising of Grass Seeds, and Training Lint and Hemp, which was printed anonymously.[4]

About 1725, a society of gardeners residing in London was established, and Fairchild joined it. Meeting every month at Newhall's coffee-house in Chelsea or some similar place, they showed to each other plants of their own growing, which were examined and compared, the names and descriptions being afterwards entered in a register. After a time they decided to make known the results of their labours, and a volume was produced called A Catalogue of Trees and Shrubs both Exotic and Domestic which are propagated for Sale in the Gardens near London. It was illustrated by Jacob Van Huysum. The 'Catalogue' has been attributed to Philip Miller, who was at one time secretary of the society; but was indexed under Fairchild's name at the British Museum.[4]

Legacy

Apart from the annual "Fairchild Sermon" (see above), Fairchild's Garden remains as a public park near Columbia Road Market in Hoxton. Fairchild is honoured in the name of the Thomas Fairchild Community School, Shoreditch.

Notes

- ↑ Wulf, 6 (quoted)

- ↑ The Gentle Author (2 July 2011). "Thomas Fairchild, Gardener of Hoxton". Spitalfields Life. Retrieved 16 November 2015.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ↑ Wulf, 6-7, 14-15

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Norman 1901.

- ↑ Wulf, 10, quoted

- ↑ Art Uk, "Thomas Fairchild (c.1667–1729), unknown artist"

- ↑ Wulf, 8

- ↑ Philosophical Account of the Works of Nature, 1721.

- ↑ Wulf, 16

References

- Wulf, Andrea, The Brother Gardeners: A Generation of Gentlemen Naturalists and the Birth of an Obsession, 2008, William Heinemann (US: Vintage Books), ISBN 9780434016129

- Norman, Philip (1901). . In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography (1st supplement). London: Smith, Elder & Co.

Further reading

- Leapman, Michael (2001). The Ingenious Mr. Fairchild: The Forgotten Father of the Flower Garden. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0312276683.