Theca lutein cyst is a type of bilateral functional ovarian cyst filled with clear, straw-colored fluid. These cysts result from exaggerated physiological stimulation (hyperreactio luteinalis) due to elevated levels of beta-human chorionic gonadotropin (beta-hCG) or hypersensitivity to beta-hCG.[1][2] On ultrasound and MRI, theca lutein cysts appear in multiples on ovaries that are enlarged.[3]

Theca lutein cysts are associated with gestational trophoblastic disease (molar pregnancy), choriocarcinomas, and multiple gestations.[4][5] In some cases, these cysts may also be associated with diabetes mellitus and alloimmunisation to Rh-D. They have rarely been associated with chronic kidney disease and hyperthyroidism.[6]

Usually, these cysts spontaneously resolve after the molar pregnancy is terminated. Rarely, when the theca lutein cysts are stimulated by hormones called gonadotropins, massive ascites can result. In most cases, however, abdominal symptoms are minimal and restricted to peritoneal irritation from cyst hemorrhage.[7] Due to the enlargement of the ovaries, there is an increased risk for torsion.[3] Surgical intervention may be required to remove ruptured or infarcted tissue.[7]

Etiology

Main causes

Theca lutein cysts commonly form due to an elevated level of chorionic gonadotropin, a luteinizing hormone otherwise known as beta human chorionic gonadotropin (beta-hCG). Theca lutein cysts occur almost exclusively in pregnancy and have an increased incidence in pregnancies complicated by gestational trophoblastic disease.[8] But additionally, theca lutein cysts may develop in conditions such as placentomegaly that may accompany diabetes, anti-D alloimmunization, mutifetal gestation, and individuals undergoing fertility treatment including chorionic gonadotropin or clomiphene therapy. Theca lutein cysts are also often notably seen in patients with choriocarcinoma or hydatidiform mole.[7] Rarely these type of cysts are present in normal pregnancy. In the event they do occur in otherwise uncomplicated pregnancies they are most likely associated with elevated levels of beta-hCG.[9]

Secondary health conditions

There are some cases of chronic kidney disease (CKD) being a secondary cause of the formation of theca lutein cysts. Although not common, some case studies have shown that people with CKD have reduced clearance of human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) .[10][11] As a result, theca lutein cysts may form since there is in an increase of hCG levels in the body.

Additionally, it is reported that 10% of people with hyperreactio luteinalis can develop hyperthyroidism.[12] Although the exact mechanism is still unclear, it is suspected that hCG and thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) are closely related.[13] As a result, hCG can weakly bind to TSH receptors in the thyroid gland causing production of thyroid hormones T3 and T4.[13] Since hyperreactio luteinalis causes increased levels of hCG, hCG can thus cause overproduction of T3 and T4. Most people do not experience symptoms and to not require antithyroid treatment.[12] Overall, 0.2% of pregnant people develop clinical hyperthyroidism requiring treatment.[14]

Signs and symptoms

Characteristics

Theca lutein cysts are an uncommon type of follicular cysts that reflect a benign ovarian lesion of a physiological exaggeration of follicle stimulation often termed as hyperreactio lutealis. Theca lutein cysts are lined by theca cells that may or may not be luteinized or have granulosa cells. They are usually bilateral and are filled with clear, straw-colored fluid.[7] Overall theca lutein cysts can be characterized by the luteniziation and hypertrophy of the theca interna layer. The resulting bilateral cystic ovaries are variably enlarged that have multiple smooth-walled cysts formation and ranging in size with a diameter from 1 to 4 cm.[15]

Symptoms

Symptoms are usually asymptomatic and minimal, but hemorrhage of the cysts can cause acute abdominal pain. Additionally, a sense of pelvic heaviness or aching may be described.[7]

Maternal virilization may also occur. Signs of maternal virilization include deepening of the voice, facial hirsutism and scalp hair loss seen during the onset of pregnancy (usually towards the end of the first trimester) followed by regression several months post-partum.[16] Maternal virilization can be seen in up to 30 percent of people with this condition, however, virilization of the fetus has only rarely been reported and if so is dependent on the timing of hyperandrogenism.[17] Overall, maternal findings including temporal balding, hirsutism, and clitoromegaly are associated with massively elevated levels of androstenedione and testosterone.[9] Additionally, continued signs and symptoms of pregnancy, especially hyperemesis and breast paresthesias, are also reported in cases of histologically proven theca lutein cysts.[7]

An occurrence of a ruptured cysts may result in intraperitoneal bleeding. In this case, symptoms may mimic the signs of a hemorrhagic corpus luteum cyst.[7]

Diagnosis

Physical examination

Theca lutein cysts are detected and diagnosed during a pelvic examination followed by a thorough evaluation. The evaluation includes a collection of the person's age, family history, and previous histories of ovarian or breast cancers. A full physical examination is performed to check for tenderness, peritoneal signs, and a frozen pelvis.[7]

Imaging

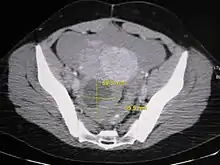

Further work up involves imaging, such as a pelvic ultrasound or CT scan.[7] Theca lutein cysts with diameters over 6 cm in size can be seen through these imaging modalities.[18] Benign ovarian cysts and complex cysts that are potentially malignant are distinguishable via ultrasounds.[19] Labs are also collected to evaluate leukocytes and tumor markers, such as beta-hCG and cancer antigen 125 (CA125).[20]

During pregnancy, ultrasonography is the first-line method for evaluating ovarian cysts. Both transabdominal and transvaginal route of ultrasonography are used with either two-dimensional or three-dimensional modalities.[3] Two-dimensional is more common, but three-dimensional can offer more results.[3] Doppler ultrasonography can also be used and is helpful at analyzing the characteristics of the cyst.[3] It can identify the presence of color flow within a septum as well as the presence of a solid component of the mass.[3] Ultrasonography is an effective tool for observing the progression or regression of the cyst.[3] Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the second-line method used when ultrasonography cannot detect the cyst.[3] Cysts that are too large to be accurately analyzed by ultrasonography are typically when MRI would be used.[3] The advantages of MRI are its larger field of view and multiplanar capabilities.[21] In addition, pathologies such as infarctions and placental invasive disorders can be seen more clearly.[3] MRI is especially beneficial in gestational age and obese people.[3] MRI is also beneficial at preventing the exposure of ionizing radiation to the fetus during pregnancy.[22] Both ultrasonography and MRI show enlarged ovaries with multiple theca lutein cysts.[3]

Risks

Risk factors

Oral contraceptives containing only progestin can increase the occurrence of follicular cysts. The use of levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG-IUS) or progestin implants are also associated with the occurrence of follicular cysts.[20]

People who are of pre- and postmenopausal age with breast cancer and are being treated with tamoxifen are at increased risk for the development of benign ovarian cysts. However, many of these cysts are functional and can resolve with time.[20] Tamoxifen treatment can be continued unless the cyst is found to be malignant.[20]

People with hyperandrogenism, which can occur in polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS), are at risk for developing hyperreactio luteinalis.[3]

Smoking can also cause an increased risk for functional cysts.[20]

Treatments

Theca lutein cysts usually spontaneously resolve on their own after the source of hormonal stimulation is removed such as the removal of the molar pregnancy, removal of the choriocarcinoma, stopping fertility therapy or after delivery.[7][20] It may take months for the cysts to resolve on their own.[7] Treatment for theca lutein cysts is very conservative due to their benign nature and ability to disappear after the removal of hormonal stimulation.[17] Individual patient characteristics must be taken into consideration when deciding whether or not to treat the cyst. These patient factors include: (1) size of cyst and whether or not it is benign or malignant, (2) patient symptoms, (3) patient age, and (4) impact of cyst on the pregnancy.[23] Benign cysts less than 6 cm are more likely to spontaneously resolve over time.

Surgical treatments may be needed for serious complications due to theca lutein cysts. Surgery is considered when the cyst is considered malignant or when signs of torsion and hemorrhage are present.[7][23] Removal of the ovaries may also be performed if large areas of tissue continue to infarct despite resolving the torsion.[24]

Surgery due to ovarian torsion

Ovarian cysts such as theca lutein cysts can cause ovarian torsion. Torsion occurs when the cysts enlarge the ovaries, causing an imbalance resulting in the twisting of the fallopian tubes.[25] As a result, blood flow to the ovaries is restricted which can cause infarction of the tissue. This requires prompt surgical treatment.[25] Detorsion surgery is done laparoscopically, often trying to keep the ovaries functional.[25] Laparoscopic surgery is minimally invasive procedure where only a small incision is made and a small camera is inserted at the site of procedure. Laparoscopic surgery is safe to do during the first half of pregnancy, but risk of uterus and fetus injury increases after 20 weeks of pregnancy.[23] Laparotomy is considered if the cyst is malignant and too large to remove laparoscopically.[26] A laparotomy is preferred during the third trimester of pregnancy.[23] This procedure is more invasive than a laparoscopic surgery and involves a larger incision.

Surgery due to hemorrhage

Theca lutein cysts have the potential to rupture and hemorrhage resulting in acute abdominal pain as well as intraperitoneal bleeding.[7][24] Laparoscopic surgery is performed to control bleeding and remove unwanted blood clots and fluid.[27] The cyst is then removed surgically. A laparotomy may need to be performed if the cyst is large or more complicated.[26]

Cyst aspiration

In some cases, the cyst can be reduced of its volume through aspiration. This procedure aims to drain the fluid from the cyst, as a result decreasing the size of the cyst preventing risk of torsion or as a method of detorsion. This method of treatment is considered when there are reasons to not treat conservatively or if there are high risks associated with surgery.[23] This treatment is done with the guidance of radiology and is done for symptomatically large cysts.[23]

Other considerations

Misdiagnosis

Despite classification of a benign condition, hyperreactio lutealis can potentially mimic a malignancy in pregnancy leading to a misdiagnosis amongst physicians. The fear of missing a cancer diagnosis often leads to often unnecessary surgical intervention. As a result these interventions may lead to impaired future fertility. Not much literature evidence is fully discussed and still needs to go under further investigation. Despite current knowledge, treatments for conditions still remain the same.[17]

As previously mentioned, an occurrence of a ruptured cysts that result in intraperitoneal bleeding share symptoms may mimic signs and symptoms of hemorrhagic corpus luteum cyst.[7]

Effects on fetus

Despite its notable presentation, ovarian enlargement and increased androgen presence, hyperreacto lutenilais is a self-limiting condition with resolution at postpartum. As a result, the condition presents itself without much after-effect on both mother and fetus[17] Fetal virilization is rare, and more dependent on the timing of increased androgen presence. Therefore most of the effects are present to the mother through maternal viralization.[17]

Most associated adverse pregnancy outcomes are due to an abnormally high observed beta-hCG levels during gestation. As a result, the subset of pregnant people in these abnormal values should be considered for enhanced surveillance. Discussion on vaginal delivery is preferred in addition to potential breastfeeding strategies to be introduced while maternal androgen levels fall in order to sustain breastfeeding and lactation for this condition.[17]

Post-complications

Some possible post-complications that have been associated with abnormally raised levels of hCG can be seen in the potential development of pre-eclampsia,[28][29] HELLP syndrome,[30] eclampsia[31] and hypothyroidism.[13] In most cases, most case reports discuss the prevalence of preeclampsia and preterm contractions and delivery[32][28] in association with high hCG levels. It is hypothesized that these elevated levels are possibly contribute to incomplete placental invasion and inadequate angiogenesis.[28]

References

- ↑ Kaňová N, Bičíková M (2011). "Hyperandrogenic states in pregnancy". Physiological Research. 60 (2): 243–252. doi:10.33549/physiolres.932078. PMID 21114372.

- ↑ Rukundo J, Magriples U, Ntasumbumuyange D, Small M, Rulisa S, Bazzett-Matabele L (2017). "EP25.13: Theca lutein cysts in the setting of primary hypothyroidism". Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology. 50: 378. doi:10.1002/uog.18732.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Yacobozzi M, Nguyen D, Rakita D (February 2012). "Adnexal masses in pregnancy". Seminars in Ultrasound, CT, and MR. Multimodality Imaging of the Pregnant Patient. 33 (1): 55–64. doi:10.1053/j.sult.2011.10.004. PMID 22264903.

- ↑ Lauren N, DeCherney AH, Pernoll ML (2003). Current obstetric & gynecologic diagnosis & treatment. New York: Lange Medical Books/McGraw-Hill. p. 708. ISBN 0-8385-1401-4.

- ↑ William's Obstetrics (24th ed.). McGraw Hill. 2014. p. 50. ISBN 978-0-07-179893-8.

- ↑ Coccia ME, Pasquini L, Comparetto C, Scarselli G (February 2003). et al. "Hyperreactio luteinalis in a woman with high-risk factors. A case report". The Journal of Reproductive Medicine. 48 (2): 127–129. PMID 12621799.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Lavie O (2019). "Benign Disorders of the Ovaries & Oviducts". In DeCherney AH, Nathan L, Laufer N, Roman AS (eds.). CURRENT Diagnosis & Treatment: Obstetrics & Gynecology (12th ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Education.

- ↑ Elami-Suzin M, Freeman MD, Porat N, Rojansky N, Laufer N, Ben-Meir A (October 2013). "Mifepristone followed by misoprostol or oxytocin for second-trimester abortion: a randomized controlled trial". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 122 (4): 815–820. doi:10.1097/aog.0b013e3182a2dcb7. PMID 24084539. S2CID 39473570.

- 1 2 Casey BM, Dashe JS, Spong CY, McIntire DD, Leveno KJ, Cunningham GF (May 2007). "Perinatal significance of isolated maternal hypothyroxinemia identified in the first half of pregnancy". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 109 (5): 1129–1135. doi:10.1097/01.aog.0000262054.03531.24. PMID 17470594. S2CID 9486153.

- ↑ Chen EM, Breiman RS, Sollitto RA, Coakley FV (December 2007). "Pregnancy in chronic renal failure: a novel cause of theca lutein cysts at MRI". Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging. 26 (6): 1663–1665. doi:10.1002/jmri.21168. PMID 18059008. S2CID 22160271.

- ↑ al-Ramahi M, Leader A (February 1999). "Hyperreactio luteinalis associated with chronic renal failure". Human Reproduction. 14 (2): 416–418. doi:10.1093/humrep/14.2.416. PMID 10099989.

- 1 2 Aghajanian P, Rimel BJ (2019). "Gestational Trophoblastic Diseases". In DeCherney AH, Nathan L, Laufer N, Roman AS (eds.). CURRENT Diagnosis & Treatment: Obstetrics & Gynecology (12th ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Education.

- 1 2 3 Braunstein G (October 2009). "Thyroid function in pregnancy". Clinical Thyroidology for the Public. American Thyroid Association. 2 (6): 5–6.

- ↑ Fitzgerald PA (2022). Papadakis MA, McPhee SJ, Rabow MW, McQuaid KR (eds.). Hyperthyroidism (Thyrotoxicosis). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Education.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ↑ Schorge J, Schaffer J, Halvorson L, Hoffman B, Bradshaw K, Cunningham F (2010-07-08). "Williams Gynecology". Journal of Midwifery & Women's Health. 55 (4). doi:10.1016/j.jmwh.2010.05.004. ISSN 1526-9523.

- ↑ "Maternal virilization in pregnancy (Concept Id: C4024735) - MedGen - NCBI". www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Malinowski AK, Sen J, Sermer M (August 2015). "Hyperreactio Luteinalis: Maternal and Fetal Effects". Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada. 37 (8): 715–723. doi:10.1016/s1701-2163(15)30176-6. PMID 26474228.

- ↑ Lima LL, Parente RC, Maestá I, Amim Junior J, de Rezende Filho JF, Montenegro CA, Braga A (2016). "Clinical and radiological correlations in patients with gestational trophoblastic disease". Radiologia Brasileira. 49 (4): 241–250. doi:10.1590/0100-3984.2015.0073. PMC 5073391. PMID 27777478.

- ↑ Montes de Oca MK, Dotters-Katz SK, Kuller JA, Previs RA (July 2021). "Adnexal Masses in Pregnancy". Obstetrical & Gynecological Survey. 76 (7): 437–450. doi:10.1097/OGX.0000000000000909. PMID 34324696. S2CID 236324402.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Hoffman BL, Schorge JO, Halvorson LM, Hamid CA, Corton MM, Schaffer JI (2020). "Benign Adnexal Mass". Williams Gynecology (4 ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Education.

- ↑ Dekan S, Linduska N, Kasprian G, Prayer D (May 2012). "MRI of the placenta - a short review". Wiener Medizinische Wochenschrift. 162 (9–10): 225–228. doi:10.1007/s10354-012-0073-4. PMID 22717878. S2CID 19768549.

- ↑ Oto A, Ernst R, Jesse MK, Saade G (2008-07-01). "Magnetic resonance imaging of cystic adnexal lesions during pregnancy". Current Problems in Diagnostic Radiology. 37 (4): 139–144. doi:10.1067/j.cpradiol.2007.08.002. PMID 18502322.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Bhagat N, Gajjar K (2022). "Management of ovarian cysts during pregnancy". Obstetrics, Gynaecology & Reproductive Medicine. 32 (9): 205–210. doi:10.1016/j.ogrm.2022.06.002. ISSN 1751-7214. S2CID 250326018.

- 1 2 Cunningham FG, Leveno KJ, Dashe JS, Hoffman BL, Spong CY, Casey BM (2022). "Gestational Trophoblastic Disease". Williams Obstetrics (26th ed.). New York, NY: McGraw Hill.

- 1 2 3 Guile SL, Mathai JK (2022). "Ovarian Torsion". StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. PMID 32809510.

- 1 2 "Ovarian cyst - Treatment". United Kingdom National Health Service. 2018.

- ↑ "Management of Ruptured Ovarian Cyst". Johns Hopkins Medicine. 2021.

- 1 2 3 Atis A, Cifci F, Aydin Y, Ozdemir G, Goker N (July 2010). "Hyperreactio luteinalis with preeclampsia". Journal of Emergencies, Trauma, and Shock. 3 (3): 298. doi:10.4103/0974-2700.66545. PMC 2938501. PMID 20930978.

- ↑ Masuyama H, Tateishi Y, Matsuda M, Hiramatrsu Y (July 2009). "Hyperreactio luteinalis with both markedly elevated human chorionic gonadotropin levels and an imbalance of angiogenic factors subsequently developed severe early-onset preeclampsia". Fertility and Sterility. 92 (1): 393.e1–393.e3. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.04.002. PMID 19446290.

- ↑ Grgic O, Radakovic B, Barisic D (November 2008). "Hyperreactio luteinalis could be a risk factor for development of HELLP syndrome: case report" (PDF). Fertility and Sterility. 90 (5): 2008.e13–2008.e16. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.06.053. PMID 18829007.

- ↑ Gatongi DK, Madhvi G, Tydeman G, Hasan A (July 2006). "A case of hyperreactio luteinalis presenting with eclampsia". Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 26 (5): 465–467. doi:10.1080/01443610600759244. PMID 16846881. S2CID 32235924.

- ↑ Lynn KN, Steinkeler JA, Wilkins-Haug LE, Benson CB (July 2013). "Hyperreactio luteinalis (enlarged ovaries) during the second and third trimesters of pregnancy: common clinical associations". Journal of Ultrasound in Medicine. 32 (7): 1285–1289. doi:10.7863/ultra.32.7.1285. PMID 23804351. S2CID 20652763.