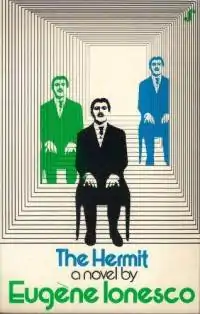

The Hermit (French title Le Solitaire), published in 1973, is the only novel written by the Romanian-French absurdist playwright Eugène Ionesco.

Summary

The Hermit follows an unnamed middle-aged Frenchman—a solitary, ineffectual clerk—who inherits a great deal of money after the death of his American uncle. He responds to this sudden wealth by quitting the job he has been working at for 15 years, and moving to a very nice apartment in the suburbs, where he bathes and shaves, reads the newspaper, eats lunch, dinner, drinks too much, thinks about death, and then attempts to sleep. He speaks to a psychiatrist, who reassures him that a fear of death is very common. He angrily responds by saying that the fear may be common, but it is very real. He points out:

Despair has been domesticated; people have turned it into literature, into works of art. That doesn't help me. It's part of culture, part of culture. So much the better for you if culture has succeeded in exorcising man's drama, his tragedy.[1]

He has a brief affair with a waitress, but it doesn't ease his anxiety. She leaves him, and he, the unnamed Frenchman, can't remember her name. When violence breaks out near his home, he joins the revolutionaries in the street—and imagines it is a demonstration of his own inner catastrophe, in which unexpected fortune has only led to loneliness, despair, and madness.

Characters

- The hermit, an office clerk, who is not named

- Jacques Dupont, a friend he works with

- Ex-Girlfriends, Lucienne, Jeanine, and Juliette

Interpretation

Edmund White, reviewing The Hermit in The New York Times in 1974 says that in this novel Ionesco elaborates "with great skill" a theme that has occurred in some of his plays—a fear of death. White says that the fear "is not a fashionable intellectual posture, but rather an abiding visceral pain." White illustrates this with a passage from the novel:

And then all of a sudden, unexpectedly as it always is when it leaps upon me, suddenly the idea that I'm going to die. I shouldn't be afraid of death, since I don't know what death is, and besides, haven't I said that I ought to give in and not fight it? To no avail. I jump out of bed, frightened out of my wits, I turn on the lights, run from one end of the room to the other, dash into the living room, turn on the lights there. When lie down I can't lie still; the same when I sit or stand. So I move, I move, to and fro throughout the house; I light and I run.

White suggests that "It is death that makes all human activities, not just bourgeois manners, absurd; in the light of mortality every motive looks mad", and that Ionesco has created a little fool, who inherited a lot of money, and who then attempts to solve problems of humanity, such as "alienation, the nature of the infinite, existential dread, determinism and so on."[1]

References

- 1 2 White, Edmund (October 27, 1974). "Eugene Ionesco: In the light of mortality every motive looks mad". The New York Times.