| The Greatest Story Ever Told | |

|---|---|

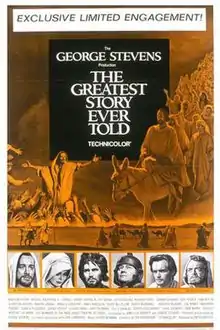

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | George Stevens |

| Screenplay by | George Stevens James Lee Barrett |

| Based on | The Greatest Story Ever Told by Fulton Oursler Henry Denker Bible |

| Produced by | George Stevens |

| Starring | Max von Sydow José Ferrer Charlton Heston Dorothy McGuire |

| Cinematography | Loyal Griggs William C. Mellor |

| Edited by | Harold F. Kress Argyle Nelson Jr. Frank O'Neil |

| Music by | Alfred Newman |

Production company | George Stevens Productions |

| Distributed by | United Artists |

Release date |

|

Running time | 199 minutes (see below) |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $20 million[1] |

| Box office | $15.5 million[2] |

The Greatest Story Ever Told is a 1965 American epic religious film about the retelling of the Biblical account about Jesus of Nazareth, from the Nativity through to the Ascension. Produced and directed by George Stevens, with an ensemble cast, it features the final film performances of Claude Rains and Joseph Schildkraut.

The Greatest Story Ever Told originated as a half-hour radio series in 1947, inspired by the four canonical Gospels. The series was later adapted into a 1949 novel by Fulton Oursler. In 1954, Twentieth Century Fox acquired the film rights to Oursler's novel, but development stalled for several years. In November 1958, Stevens became involved with the project, in which he agreed to write and direct. However, in September 1961, Fox withdrew from the project because of financial uncertainty concerning its presumptive cost and its thematic similarities with King of Kings (1961), another religious biopic of Jesus.

A few months later, Stevens moved the project to United Artists. Stevens decided not to film the project in the Middle East, but instead in the Southwestern United States, for which principal photography began on October 29, 1962. Filming fell behind schedule due to Stevens' tedious shooting techniques, in which David Lean and Jean Negulesco were brought in to film other sequences. The film wrapped on August 1, 1963.

The film premiered at the Warner Cinerama Theatre in New York City on February 15, 1965. It received five Academy Award nominations.

Plot

Part I

Three wise men (Magi) follow a brightly shining star from Asia to Jerusalem in search of the newborn king it portents. They are summoned by King Herod the Great, whose advisers inform him of a Messiah mentioned in various prophecies. When Herod remembers that a prophecy names nearby Bethlehem as the child's birthplace, he sends the Magi there to confirm the child's existence, but secretly sends guards to follow them and to "keep [him] informed." In Bethlehem, the Magi find a married couple, Mary and Joseph, who are laying their newborn son in a manger. Mary states that the child's name is Jesus. As the local shepherds watch, the Magi present gifts of gold, frankincense, and myrrh to the infant. After observing the distant spies' departure, the magi leave, then an angel's voice warns Joseph to "take the child" and "flee."

The spies inform Herod of what has occurred, and he decides to kill the child by ordering the death of every new-born boy in Bethlehem. He dies after being informed that "not one is alive." However, Joseph and Mary have escaped into Egypt with Jesus. Later when a messenger inform the couple and others of Herod's death, they return to their hometown of Nazareth.

A pro-Israel rebellion breaks out in Jerusalem against Herod's son, Herod Antipas, but the conflict is quickly quashed. Herod's kingdom is divided, Judea is placed under a governor, and Herod becomes tetrarch of Galilee and the Jordan River. Both he and the Romans are convinced that the Messiah that the troubled people cry for, is "someone who will never come."

Many years later, a prophet named John the Baptist begins to preach at the Jordan river, baptizing many who come to repent. Now an adult, Jesus appears to John who baptizes him. Jesus then goes into the nearby desert mountains, where he finds a cave in which resides a mysterious hermit, the personification of Satan. The Dark Hermit tempts Jesus three times, but each temptation is overcome by Jesus, who leaves and continues climbing as John's message echoes in his mind.

He returns to the valley, where he tells the Baptist that he is returning to Galilee. Four men, Judas Iscariot and the Galilean fishermen Andrew, Peter, and John, ask to go with him. Jesus welcomes them, promising to make them "fishers of men." He tells them parables and other teachings, which attract the attention of a passing young man named James, who asks to join them the next morning, and Jesus welcomes him. The group nears Jerusalem, and Jesus says that "there will come a time to enter". They rest at Bethany in the home of Lazarus and his sisters Martha and Mary. Lazarus asks Jesus if he can join him, but cannot bring himself to leave all he has. Before he leaves, Jesus promises Lazarus that he will not forget him.

The group soon arrives at Capernaum, where they meet James's brother Matthew, a tax collector whom Jesus soon asks to join them. After consideration, Matthew does so. In the local synagogue, Jesus once again teaches, then miraculously helps a crippled man to walk again. Upon seeing this, many people begin to follow Jesus on his journey and gather to listen to his teachings.

Meanwhile, the Jerusalem priests and Pharisees are troubled by the continuing influence and preaching of John the Baptist, while the governor Pontius Pilate wishes only to maintain peace. Since the Jordan is ruled by Herod, he permits the priests to inform him of what is occurring. When he hears that the Baptist is speaking of a Messiah, Herod sends soldiers to arrest him. Simon the Zealot informs Jesus and his disciples of the Baptist's arrest, and then he is welcomed as one of them.

The fame of Jesus begins to spread across the land and two more men, named Thaddeus and Thomas, join him. In Jerusalem, the priests become suspicious of Jesus and the curing of the cripple, and send a group to Capernaum to investigate, including the Pharisees Nicodemus and Joseph of Arimathea. Herod hears rumours about an army as a result of the multitudes that follow Jesus. He questions John the Baptist about him. Later Herod begins to consider killing the Baptist, with his wife's encouragement. His wife is the ex-wife of Herod's brother, and has been verbally attacked by John for being an adulteress.

Jesus is soon asked to return to Capernaum by another man named James. Crowds gather and celebrate his return, something that is noticed by the Pharisees who are present and the returned Dark Hermit. Jesus then defends a woman caught in the act of adultery, who identifies herself as Mary Magdalene. Among the crowd that gathers as he moves away is a sick woman who is cured when she touches his clothes. As word of these incidents spreads, the number of people who believe that Jesus is the Messiah increases even further.

Herod begins to wonder about Jesus, and the Baptist confirms that Jesus has escaped from the massacre ordered by Herod's father. Herod then decides to finally kill the Baptist by beheading, which occurs after Salome, Herod's stepdaughter by his wife's first marriage, dances for him. When the Baptist is dead, Herod sends soldiers to arrest Jesus.

Jesus teaches a sermon on a mountain to a great crowd. Pilate and the Pharisees hear of many of Jesus's miracles such as turning water into wine, feeding five thousand people, and walking on water. Meanwhile, Jesus asks his disciples who they and others say that he is. They respond with different answers, and Peter says that he believes that Jesus is the Messiah, prompting Jesus to anoint him as "the rock on which [he] will build [his] church."

At Nazareth, the people refuse to believe in Jesus and his miracles and demand to see for themselves by bringing a blind man named Aram and demanding that Jesus make him see. When he does not, the people are disgusted that he dare call himself the Son of God, and briefly try to stone him. Later Jesus reunites with his mother, and greets Mary, Martha as well as their brother Lazarus who is sick. After Andrew and Nathaniel escort Lazarus to his home in Bethany, Jesus heals Aram's sight. As Herod's soldiers draw nearer, Jesus and the others flee. When informed that Lazarus is dying, Jesus does not go immediately to Bethany, but to the Jordan with the group where he prays. Andrew and Nathaniel return, informing them that Lazarus has died, and Jesus travels to Bethany where he brings Lazarus back to life, a miracle that astonishes the citizens of Jerusalem who witness it, but concerns the Pharisees.

Part II

Judas questions why Mary Magdalene is anointing Jesus with expensive oil, and Jesus states she is preparing him for his death. Jesus then dons a new garment, and rides on a donkey into Jerusalem. In the courtyard of the Temple, Jesus is angered by the merchants selling items for sacrifices, and drives them and money changers away. Even though it is Passover, the Pharisees' attempt to arrest Jesus are impeded by the large crowd. In the Temple courtyard, Jesus begins to teach, but leaves after Pilate dispatches soldiers to restore peace and close the gates, and many in the crowd are killed.

While the disciples gather to prepare and partake in an evening meal, Judas leaves to meet with the Pharisees where he promises to hand Jesus over to them on the condition that no harm comes to him. When Judas returns to the meal, Jesus announces to all that one of them will betray him, and says that by morning, Peter will deny three times that he even knows Jesus. He gives a farewell discourse, then shares the bread and wine with the disciples. After that he tells Judas to "do quickly what you have to do," and Judas leaves again.

Later, Jesus goes to Gethsemane to pray while Judas returns to the Pharisees and is paid thirty pieces of silver to lead soldiers to arrest Jesus. When they arrive in Gethsemane, Judas kisses Jesus to indicate that he is the man to be arrested. Knowing that Judas has betrayed him, Jesus orders Peter to "put back [his] sword," and goes quietly with the soldiers. He is put on trial before the Sanhedrin, and Aram appears as one of the questioned witnesses. Many of the members are present, but Nicodemus refuses to take part, and realizes that some (including Joseph of Arimathea) are absent. Meanwhile, the Dark Hermit asks Peter if he knows Jesus. Peter denies it twice and leaves. When Caiaphas asks Jesus if he is the Christ, Jesus's reply causes the members to condemn him.

The Pharisees and Caiaphas bring Jesus to the tired Pilate, who after questioning Jesus, and briefly speaking with his wife, can find no guilt in Jesus. Since Galilee is under Herod's authority, Jesus is sent to Herod, though he and his soldiers merely ridicule him and send him back to Pilate. As Jesus is escorted back to Pilate, the Hermit continues to observe, and Peter once again denies Jesus, as a remorseful Judas looks on.

In the morning, Pilate presents Jesus before the assembled crowd, and the Hermit cries out several times for Jesus to be crucified. Pilate offers compromises, suggesting that Jesus merely be scourged, and for the release of a prisoner of the crowd's choice. The crowd chooses the alleged murderer Barabbas instead. Pilate asks Jesus if he has anything to say, but Jesus merely states that his kingdom is "not of this world," something that the Hermit and others claim is a challenge to the authority of Rome and the Roman emperor. With no other choice, Pilate reluctantly orders Jesus to be crucified.

Jesus then carries his cross through Jerusalem while the crowd looks on. When he collapses, a woman wipes his face, and he reassures the pious women. As Jesus falters, Simon of Cyrene, a man from the crowd, helped Jesus to carry the cross. At Golgotha, Jesus is stripped and nailed to the cross, which is then raised between those of two other men. At the same time this is happening, Judas tosses his silver into the Temple, then throws himself into the fire of the nearby altar.

From the cross, Jesus intercedes for his executioners, asking God to forgive them. He then asks John to care for his mother. One of the thieves on the other crosses, asks Jesus to save him, while the other accepts his punishment and asks for Jesus to remember him, a promise that Jesus gives to him. Darkness begins to cover the sky, and from the cross, Jesus asks why God has forsaken him. He is offered a drink from a wine soaked sponge, and dies as the storm erupts. A centurion states that he was the "Son of God."

Peter mourns as Jesus is being laid to rest in the tomb of Joseph of Arimathea. The Pharisees ask for Pilate to place guards around the tomb and seal it, to prevent a possible theft of the corpse that could potentially fulfil a prophecy of His resurrection. Pilate agrees, but on the morning of the third day the guards soon discover that the tomb is open and empty. Meanwhile, though Thomas's faith has weakened, Mary Magdalene, along with Peter and others, recall the prophecy and run to see the empty tomb, where an Angel tells Mary that he is risen. Word of the miraculous event quickly spreads throughout Jerusalem, bewildering the Pharisees. Caiaphas claims that "the whole thing will be forgotten in a week," though an elder scribe doubts it.

Later, while he was with his disciples, Mary Magdalene, Nicodemus, Joseph of Arimathea, and others, Jesus ascends to heaven, leaving them with his final commands as clouds engulf him. He then states that he will always be with them, "even unto the end of the world," and his image fades into the clouds, and to a painting of him on the church wall as Handel's "Hallelujah Chorus" plays.

Cast

- Max von Sydow as Jesus

- Dorothy McGuire as the Virgin Mary

- Charlton Heston as John the Baptist

- Claude Rains as Herod the Great

- José Ferrer as Herod Antipas

- Telly Savalas as Pontius Pilate

- Martin Landau as Caiaphas

- David McCallum as Judas Iscariot

- Gary Raymond as Peter

- Donald Pleasence as "The Dark Hermit"

- Michael Anderson Jr. as James the Less

- Roddy McDowall as Matthew

- Joanna Dunham as Mary Magdalene

- Joseph Schildkraut as Nicodemus

- Ed Wynn as "Old Aram"

- Sidney Poitier as Simon of Cyrene

Smaller credited roles (some only a few seconds) were played by Michael Ansara, Carroll Baker, Ina Balin, Robert Blake, Pat Boone, Victor Buono, John Considine, Richard Conte, John Crawford, Cyril Delevanti, Jamie Farr, David Hedison, Van Heflin, Russell Johnson, Angela Lansbury, Mark Lenard, Robert Loggia, John Lupton, Janet Margolin, Sal Mineo, Nehemiah Persoff, Sidney Poitier, Marian Seldes, David Sheiner, Abraham Sofaer, Paul Stewart, Michael Tolan, John Wayne, and Shelley Winters. Richard Bakalyan and Marc Cavell, in uncredited roles, played the thieves crucified with Jesus.

Production

Development

The Greatest Story Ever Told originated as a U.S. radio series in 1947, half-hour episodes inspired by the four canonical Gospels, written by Henry Denker. The series was adapted into a 1949 novel by Fulton Oursler, a senior editor at Reader's Digest. In May 1954, Darryl F. Zanuck, the chairman of 20th Century Fox, acquired the film rights to Oursler's novel for a down payment of $110,000 plus a percentage of the gross.[3] Denker wrote a draft of the script, but Fox never brought it to pre-production.[4] When Zanuck left the studio in 1956, the project was forgotten.[4] In September 1958, Philip Dunne briefly became involved with the project after signing on as a producer.[5]

In November 1958, while George Stevens was filming The Diary of Anne Frank (1959) at 20th Century Fox, he became aware that the studio had owned the rights to the Oursler property. Stevens then founded a company, "The Greatest Story Productions", to film the novel.[6] The studio set the initial production budget of $10 million, twice their previous biggest. That same month, another religious biopic titled King of Kings (1961) was in development helmed by producer Samuel Bronston.[7] Spyros Skouras, the new chairman of 20th Century Fox, had attempted to purchase the project from Bronston and Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, which had agreed to distribute the film, but was unsuccessful. In June 1960, 20th Century Fox resigned from the Motion Picture Association of America, partly due to the similarly themed films.[8]

In June 1960, Denker sued Fox to reclaim the film rights and for $2.5 million of damages, claiming the studio had failed to release the film before the end of 1959. When Denker and Oursler's estate had sold the rights to Fox, Denker had placed a clause in the contract dictating the agreement.[4][9] In September 1961, 20th Century Fox announced it had "indefinitely postponed" from the project. Skouras declined to explain the reasons for canceling the project, but the decision was made after the studio had posted a $13 million loss the year before.[10] Variety also reported that in the wake of the yet-to-be released King of Kings (1961), starring Jeffrey Hunter as Jesus, several studio board members had expressed concern at the production costs, with more than $1 million spent on script preparation and no established filming date. The studio agreed to reimburse the film rights to Stevens, whereby the studio will recoup the costs after the film earned $5 million in profits.[11] That same month, four American film studios—including Magna Theatre Corporation—and two in Europe made offers to finance the film.[12] By November 1961, Stevens had moved the project to United Artists.[13]

Writing

The screenplay took two years to write. Before writing the screenplay, Stevens reviewed 36 different translations of the New Testament and compiled an extensive reference book with various clippings of scripture.[14] Stevens and David Brown, a Fox executive, considered numerous screenwriters, including Ray Bradbury, Reginald Rose, William Saroyan, Joel Sayre, and Ivan Moffat.[15] Stevens then met with Moffat at the Brown Derby, where Stevens told him his vision for the film would be reverent and universal.[16] Stevens collaborated with him and then with James Lee Barrett. It was the only time Stevens received screenplay credit for a film he directed.

By July 1960, Carl Sandburg had been hired for completion work on the screenplay.[17] Sandburg remained with the project for the next thirteen months, before returning to his residence in Flat Rock, North Carolina. In September 1961, Sandburg told Variety that he would further consult on the project "until George Stevens tells me to stop".[18] Among the contributions Sandburg made was a brief conversation between Judas Iscariot and Mary Magdalene discussing the anointing of Jesus. He received screen credit for "creative association".[19] Sandburg also had a uncredited appearance as a Roman citizen glaring at Pilate when he relents to the crowd to have Jesus crucified..

Financial excesses began to grow during pre-production. Stevens commissioned French artist André Girard to prepare 352 oil paintings of Biblical scenes to use as storyboards. Stevens traveled to the Vatican to see Pope John XXIII for advice.[14]

Casting

For the role of Jesus, Stevens had wanted an actor unknown to international audiences, free of secular and unseemly associations in the mind of the public.[20] In February 1961, Stevens cast Swedish actor Max von Sydow as Jesus. Von Sydow had never appeared in an English-language film and was best known for his performances in Ingmar Bergman's dramatic films.[21] Von Sydow stated, "I thought with horror of Cecil B. DeMille and such things as Samson and Delilah and The Ten Commandments. But when I saw the script, I decided that the role of Jesus is absolutely not a religious cliché."[22] It was also reported that Elizabeth Taylor was to portray Mary Magdalene, while Marlon Brando and Spencer Tracy were discussed to portray Judas Iscariot and Pontius Pilate respectively.[22]

The Greatest Story Ever Told features an ensemble of well-known actors, many in brief, even cameo, appearances. Some critics would later complain that the large cast distracted from the solemnity, notably in the appearance of John Wayne as the Roman centurion who commands the execution detail, and who comments on the Crucifixion, in his well-known voice, by stating: "Truly this man was the Son of God."[23] "It is impossible for those watching the film to avoid the merry game of 'Spot the Star', and the road to Calvary in particular comes to resemble the Hollywood Boulevard 'Walk of Fame'."[24]

Filming

In late April 1960, Stevens, his son George Jr., and researcher Tony Van Renterghem spent six weeks scouting potential locations for filming in Europe and the Middle East.[25] However, in 1965, Stevens told The New York Times: "Unfortunately some of the landscapes around Jerusalem were exciting, but many had been worn down through the years by erosion and man, invaders and wars, to places of less spectacular aspects."[26] Stevens then decided to film in the United States, explaining: "I wanted to get an effect of grandeur as a background to Christ, and none of the Holy Land areas shape up with the excitement of the American southwest. ... I know that Colorado is not the Jordan, nor is Southern Utah Palestine. But our intention is to romanticize the area, and it can be done better here."[27]

Principal photography began on October 29, 1962, at the Crossing of the Fathers along the Colorado River. The first sequence shot was the baptism of Jesus.[28] The Pyramid Lake in Nevada represented the Sea of Galilee, and Lake Moab in Utah was used to film the Sermon on the Mount. The Death Valley in California was filmed for Jesus's 40-day journey into the wilderness.[29] Sections of the film were also shot at Lake Powell, Canyonlands and Dead Horse Point in Utah.[30]

Filming was initially scheduled to last 20 weeks.[31] However, filming fell behind schedule due to Stevens ordering more than 30 different camera setups and filming multiple takes of several scenes.[32] Charlton Heston, who was portraying John the Baptist, explained, "Stevens would do two or three [takes], but he would devise more different angles from which to cover than you'd think possible. You'd finish a day's work on a scene confident that there was no other possible coverage, yet find yourself there a day or two longer while George explored further ideas."[33] Meanwhile, interior studio filming was shot at the Desilu Culver Studios for nine weeks from June 6 to July 31, 1963.[31] There, forty-seven sets were constructed to represent Jerusalem.[34] In June 1963, cinematographer William C. Mellor died of a heart attack during production; Loyal Griggs, who won an Academy Award for his cinematography on Stevens's 1953 Western classic Shane, was brought in to replace him.[32]

By the summer of 1963, Stevens had met with Arthur B. Krim, the chairman of United Artists, and agreed to allow other directors to direct several sequences so the film would be finished.[1] Fred Zinnemann contacted David Lean, asking if he would consider directing second unit for two sequences. Lean accepted the offer, to which Stevens suggested he direct the Nativity scenes. Lean declined but he decided to direct the scenes with Herod the Great. Lean cast Claude Rains as Herod the Great.[35][36] Jean Negulesco instead filmed sequences in the Jerusalem streets and the Nativity scenes.[37]

Filming ended on August 1, 1963, where Stevens had shot over six million feet of Ultra Panavision 70 film. The final production budget had spent nearly $20 million (equivalent to $191 million in 2022) plus additional editing and promotion charges, making it the most expensive film shot in the United States.[1]

Music

Alfred Newman, who had previously scored The Diary of Anne Frank (1959), composed the musical score, with the assistance of Ken Darby, his longtime collaborator and choral director. The protracted scoring process proved to be an unhappy one. Stevens, under pressure from his financers, made extensive late-stage changes to the edited footage. These edits altered the musical continuity and called for significant rewriting and reorchestration. Other composers, including Fred Steiner and Hugo Friedhofer, were called in to assist.[38]

The post-release editing of the film further disrupted the musical composition. The twin climaxes of Newman's score were his elaborate choral finales to Act 1 (the raising of Lazarus) and Act 2 (the Resurrection of Jesus). Stevens eventually substituted the Hallelujah Chorus from George Frideric Handel's Messiah for both sequences[39]—a choice that was widely ridiculed by critics. The entire experience was recalled by David Raksin as "the saddest story ever told".[40]

Release

The Greatest Story Ever Told premiered February 15, 1965, 18 months after filming wrapped, at the Warner Cinerama Theatre in New York City. It opened two days later at the Cinerama Dome in Los Angeles and then in Miami Beach.[41] The film opened in Philadelphia and Detroit on March 9, 1965, and an edited version opened March 10, 1965 at the Uptown Theater in Washington, D.C.[42] It also opened March 10 in Chicago, Cincinnati and Pittsburgh and in Boston on March 11.[42] A shorter version was released in February 1967 for its general release in Chicago.

The version that premiered in New York had a running time of 221 to 225 minutes (excluding a 10-minute intermission) per reviews from The New York Times and Variety.[43][42] The original running time was 4 hr 20 min (260 min).[44][45]

Twenty-eight minutes were cut for the release of the film in Washington D.C. to tighten the film without deleting any scenes and these cuts were later made to the other prints.[42] The film was edited further with a running time of 137 to 141 minutes for its general release in the United States.[46] This shortened version removed Jesus's 40-day journey into the wilderness, featuring Donald Pleasence as well as appearances by John Wayne and Shelley Winters.[46]

Marketing

The marketing campaign included exhibits created for churches and Sunday schools, department stores, primary schools, and secondary schools. The Smithsonian Institution put together a traveling exhibition of props, costumes, and photographs that toured museums around the country. Promotional items made available to groups identified for market segmentation included school study guides, children's books, and a reprint of the original novel by Oursler. Previews of the film were shown to leading industrialists, psychologists, government officials, religious leaders, and officials from the Boy and Girl Scout organizations.[47]

The film was advertised on its first run as being shown in Cinerama. While it was shown on an ultra-curved screen, it was with one projector. True Cinerama required three projectors running simultaneously. A dozen other films were presented this way in the 1960s.

Home media

In 1993, the film was released on LaserDisc.[48] The film was released on DVD in 2001, which featured a 3 hr 19 min (199 min) version along with a documentary called He Walks With Beauty (2011), which details the film's tumultuous production history.[49]

Reception

Critical reaction

Bosley Crowther of The New York Times described the film as the "world's most conglomerate Biblical picture" with "scenes in which the grandeur of nature is brilliantly used to suggest the surge of the human spirit in waves of exaltation and awe." However, he felt the scenes of Jesus preaching to the multitude were too repetitive and "[t]he most distracting nonsense is the pop-up of familiar faces in so-called cameo roles, jarring the illusion."[50] Robert J. Landry of Variety called the film "a big, powerful moving picture demonstrating vast cinematic resource". He also praised von Sydow's performance, writing he "is a tower of strength and sensitivity". However, he felt Stevens was "not particularly original in his approach to the galaxy of talent, some 60 roles," noting several prominent actors were underused in their cameo appearances.[43] James Powers of The Hollywood Reporter stated: "George Stevens has created a novel, reverent and important film with his view of this crucial event in the history of mankind."[51]

Time magazine wrote: "Stevens has outdone himself by producing an austere Christian epic that offers few excitements of any kind ... Greatest Story is a lot less vulgar [than Cecil B. DeMille's Biblical films], though audiences are apt to be intimidated by its pretentious solemnity, which amounts to 3 hours and 41 minutes' worth of impeccable boredom. As for vigorous ideas, there are none that would seem new to a beginners' class in Bible study."[52] Brendan Gill wrote in The New Yorker: "If the subject matter weren't sacred in the original, we would be responding to the picture in the most charitable way possible by laughing at it from start to finish; this Christian mercy being denied us, we can only sit and sullenly marvel at the energy for which, for more than four hours, the note of serene vulgarity is triumphantly sustained.[53] Shana Alexander, reviewing for Life magazine, stated: "The scale of The Greatest Story Ever Told was so stupendous, the pace was so stupefying that I felt not uplifted but sandbagged."[54] John Simon wrote: "God is unlucky in The Greatest Story Ever Told. His only begotten son turns out to be a bore."[44]

In an interview for The New York Times, Stevens stated, "I have tremendous satisfaction that the job has been done – to its completion – the way I wanted it done; the way I know it should have been done. It belongs to the audiences now ... and I prefer to let them judge."[26] On Rotten Tomatoes, the film has an approval rating of 42% based on 24 reviews, with an average rating of 4.8/10.[55]

Box office

Three weeks after opening at the Warner Cinerama, the film had earned nearly $250,000 in advance ticket sales. Based on the ticket sales and advanced reserve-seating ticket sales before Easter, Eugene Picker, United Artists vice president, told Variety that the film "was way ahead of any other previous UA hard-tickets being used up for each group and window sales."[56] By January 1968, the film had grossed $6.3 million in domestic rentals from the United States and Canada,[57] which was far less than the $35–38 million needed to break even.[58] Steven D. Greydanus, a film critic for the National Catholic Register, believed the film's inability to connect with audiences discouraged future productions of biblical epics for decades.[59][60]

Awards

Though it received a poor reception from some critics, The Greatest Story Ever Told was nominated for five Academy Awards:[61]

| Award | Date of ceremony | Category | Recipient | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Academy Awards[62] | April 18, 1966 | Best Art Direction – Set Decoration, Color | Art Direction: Richard Day, William J. Creber, and David S. Hall (posthumous nomination) Set Decoration: Ray Moyer, Fred M. MacLean, and Norman Rockett |

Nominated |

| Best Cinematography, Color | William C. Mellor (posthumous nomination) and Loyal Griggs | |||

| Best Costume Design, Color | Marjorie Best and Vittorio Nino Novarese | |||

| Best Music, Score – Substantially Original | Alfred Newman | |||

| Best Effects, Special Visual Effects | J. McMillan Johnson | |||

The film is recognized by American Film Institute in these lists:

- 2005: AFI's 100 Years of Film Scores – Nominated[63]

- 2006: AFI's 100 Years...100 Cheers – Nominated[64]

- 2008: AFI's 10 Top 10:

- Nominated Epic Film[65]

See also

- List of American films of 1965

- List of Easter films

- Cultural depictions of Jesus

- King of Kings – an earlier film about the life of Jesus, released in 1961 directed by Nicholas Ray with Jeffrey Hunter

References

- 1 2 3 Moss 2004, p. 285.

- ↑ "The Greatest Story Ever Told (1965)". The Numbers. Retrieved January 22, 2013.

- ↑ Schallert, Edwin (May 3, 1954). "Zanuck Sets $2,000,000 Biblical Deal; Kelly in 'Thief'; Murphy Steps". Los Angeles Times. Part III, p. 9. Retrieved February 4, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 3 "Denker, Original Author, Feared Crisis Now Facing 'Greatest Story'; Inside Stuff on Oursler Angle". Variety. June 29, 1960. p. 4. Retrieved February 13, 2021 – via Internet Archive.

- ↑ Pryor, Thomas M. (September 26, 1958). "Sam Jaffe Back as Moviemaker". The New York Times. Retrieved February 9, 2023.

- ↑ Pryor, Thomas M. (November 19, 1958). "Stevens To Film the Story of Christ". The New York Times. p. 45. Retrieved February 4, 2023.

- ↑ "Three Epics Based on Christ". Variety. November 26, 1958. p. 20. Retrieved May 27, 2019 – via Internet Archive.

- ↑ Weiler, A. H. (June 14, 1960). "Fox Quits Film Producers Unit; Charges Use of Similar Themes". The New York Times. p. 43. Retrieved February 4, 2023.

- ↑ "Film Rights to 'Greatest Story' Hits Legal Snag". Variety. September 13, 1961. pp. 9, 24. Retrieved February 4, 2023 – via Internet Archive.

- ↑ Archer, Eugene (September 1, 1961). "Film About Jesus Postponed by Fox". The New York Times. Retrieved February 4, 2023.

- ↑ "Stevens Will Prod. 'Greatest Story' By Jan. 1; Recoups Film Rights from Fox". Variety. September 6, 1961. pp. 3, 13. Retrieved February 4, 2023 – via Internet Archive.

- ↑ Scheuer, Philip K. (September 6, 1961). "Stevens Will Take Over Christ Story". Los Angeles Times. Part IV, p. 9. Retrieved February 9, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Schumach, Murry (November 7, 1961). "U.A. To Sponsor Film By Stevens". The New York Times. p. 38. Retrieved February 4, 2023.

- 1 2 Medved & Medved 1984, p. 135.

- ↑ Moss 2004, pp. 277–278.

- ↑ Moss 2004, p. 271.

- ↑ "Carl Sandburg on 20th's 'Greatest'". Variety. July 6, 1960. p. 24. Retrieved February 6, 2021 – via Internet Archive.

- ↑ "Sandburg Back to N.C, But Continues on 'Story'". Variety. September 20, 1961. p. 15. Retrieved February 8, 2021 – via Internet Archive.

- ↑ Moss 2004, p. 279.

- ↑ Medved & Medved 1984, p. 138.

- ↑ "Swedish Actor Gets Bible Role". Los Angeles Times. February 20, 1961. Part III, p. 6. Retrieved February 9, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 "Hollywood: No Cliché". Time. March 3, 1961. p. 70. Retrieved February 9, 2023.

- ↑ "The Greatest Story Ever Told". Turner Classic Movies.

- ↑ Medved & Medved 1984, p. 137.

- ↑ Scheuer, Philip K. (April 22, 1960). "Compassion Ideal to Guide Stevens". Los Angeles Times. Part II, p. 9. Retrieved February 9, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 Stang, JoAnne (February 14, 1965). "'The Greatest Story' in One Man's View". The New York Times. p. X7. Retrieved February 4, 2023.

- ↑ Medved & Medved 1984, pp. 136–137.

- ↑ "Stevens Rolls His 'Greatest Story'". Variety. October 31, 1962. p. 17. Retrieved February 8, 2023 – via Internet Archive.

- ↑ Land, Barbara; Myrick Land (1995). A short history of Reno. Reno, Nevada: University of Nevada Press. p. 67. ISBN 978-0-87417-262-1.

- ↑ D'Arc, James V. (2010). When Hollywood Came to Town: A History of Moviemaking in Utah (1st ed.). Layton, Utah: Gibbs Smith. ISBN 978-1-423-60587-4.

- 1 2 Hall 2002, p. 172.

- 1 2 Medved & Medved 1984, p. 140.

- ↑ Heston 1979, p. 166.

- ↑ Trombley, William (October 19, 1963). "The Greatest Story Ever Told". The Saturday Evening Post. p. 40.

- ↑ Brownlow 1996, pp. 493–495.

- ↑ Skal, David J. (2008). Claude Rains: An Actor's Voice. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-8131-2432-2.

- ↑ Capua 2017, p. 120.

- ↑ Darby 1992, p. 198.

- ↑ Darby 1992, p. 216.

- ↑ Darby 1992, p. 156.

- ↑ Balio 2009, p. 136.

- 1 2 3 4 "Trimming All 'Greatest Story' Prints 28 Mins". Daily Variety. March 10, 1965. p. 1.

- 1 2 Landry, Robert J. (February 17, 1965). "Film Reviews: The Greatest Story Ever Told". Variety. p. 6 – via Internet Archive.

- 1 2 Michalczyk, John J. (22 February 2004). "Jesus Christ, cinema star". Boston.com.

- ↑ John Walker, ed. (1993). Halliwell's Film Guide 9th edition. Harper Collins. p. 502. ISBN 0-00-255349-X.

- 1 2 Byro. (June 14, 1967). "The Greatest Story Ever Told". Variety. p. 7.

- ↑ Maresco, Peter A. (2004). "Mel Gibson's The Passion of the Christ: Market Segmentation, Mass Marketing and Promotion, and the Internet". Journal of Religion and Popular Culture. 8 (1): 2. doi:10.3138/jrpc.8.1.002. S2CID 25346049.

- ↑ Nichols, Peter M. (April 15, 1993). "Home Video". The New York Times. p. C20. Retrieved February 8, 2023.

- ↑ "DVD Verdict Review – The Greatest Story Ever Told". DVD Verdict. Archived from the original on 2008-10-24.

- ↑ Crowther, Bosley (February 16, 1965). "Screen: 'The Greatest Story Ever Told'". The New York Times. p. 40. Retrieved December 30, 2020.

- ↑ Moss 2004, p. 287.

- ↑ "Cinema: Calendar Christ". Time. February 26, 1965. p. 96. Retrieved February 4, 2023.

- ↑ Gill, Brendan (February 13, 1965). "The Current Cinema". The New Yorker. p. 88.

- ↑ Alexander, Shana (February 26, 1965). "Christ Never Tried to Please Everyone". Life. p. 25. Retrieved February 4, 2022 – via Google Books.

- ↑ "The Greatest Story Ever Told". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved February 4, 2023.

- ↑ "'Greatest Story' Crashing Through With Big Advances, Strong Run". Variety. March 17, 1965. p. 2. Retrieved February 8, 2023 – via Internet Archive.

- ↑ Frederick, Robert B. (January 3, 1968). "'Wind' May Sail Back Against 'Music'". Variety. p. 25.

- ↑ "'Greatest Story's' Slow Payoff". Variety. March 23, 1966. p. 21. Retrieved February 8, 2023 – via Internet Archive.

- ↑ Greydanus, Steven D. "The Greatest Story Ever Told (1965)". Decent Films.

- ↑ Hall 2002, p. 181.

- ↑ "NY Times: The Greatest Story Ever Told". Movies & TV Dept. The New York Times. 2012. Archived from the original on 2012-10-18. Retrieved 2008-12-26.

- ↑ "The 38th Academy Awards (1966) Nominees and Winners". oscars.org. Retrieved 2016-08-04.

- ↑ "AFI's 100 Years of Film Scores Nominees" (PDF). Retrieved 2016-08-14.

- ↑ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Cheers Nominees" (PDF). Retrieved 2016-08-14.

- ↑ "AFI's 10 Top 10 Nominees" (PDF). Archived from the original on 2011-07-16. Retrieved 2016-08-19.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

Bibliography

- Balio, Tino (2009). United Artists, Volume 2, 1951–1978: The Company That Changed the Film Industry. University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 978-0-299-23013-5.

- Brownlow, Kevin (1996). David Lean: A Biography. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-312-14578-1.

- Capua, Michelangelo (2017). Jean Negulesco: The Life and the Films. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. ISBN 978-1-476-66653-2.

- Darby, Ken (1992). Hollywood Holyland: The Filming and Scoring of The Greatest Story Ever Told. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-810-82509-3.

- Hall, Sheldon (2002). "Selling Religion: How to Market a Biblical Epic". Film History. 14 (2): 170–185. doi:10.2979/FIL.2002.14.2.170. JSTOR 3815620.

- Heston, Charlton (1979). The Actor's Life: Journals, 1956–1976. Pocket Books. ISBN 978-0-671-83016-8.

- Heston, Charlton (1995). In the Arena. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-684-80394-1.

- Medved, Harry; Medved, Michael (1984). The Hollywood Hall of Shame. Perigee Books. ISBN 0-399-50714-0.

- Moss, Marilyn Ann (2004). Giant: George Stevens, a Life on Film. University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 978-0-299-20433-4.

- Stevens, Jr., George (2022). My Place in the Sun: Life in the Golden Age of Hollywood and Washington. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-813-19541-4.