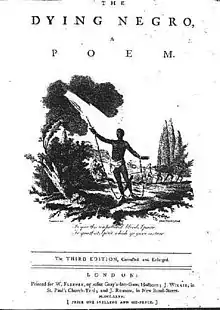

The Dying Negro: A Poetical Epistle was a 1773 abolitionist poem published in England, by John Bicknell and Thomas Day. It has been called "the first significant piece of verse propaganda directed explicitly against the English slave systems".[1] It was quoted in The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano of 1789.[2]

Details of publication

The first draft of this pioneering work of abolitionist literature was written by Bicknell. Published versions were edited by Day, from 1773.[1] The first edition was anonymous; in all there were six editions.[3]

The work was dedicated to Jean-Jacques Rousseau.[4] A substantial introduction by Day to the second edition (1774), and reproduced in later editions, attacked West Indian slaveowners, and drew a parallel with ancient Sparta.[5][6] In the fifth edition of 1793, the names of both authors appeared.[7]

Background

The poem arose from a report in the Morning Chronicle and London Advertiser of 28 May 1773. It concerned a black servant of a Captain Ordington, who had intended to marry a white woman, being taken on board the Captain's vessel on the River Thames, and shooting himself.[8] The 1772 English legal decision in Somerset v Stewart had been widely interpreted as a ruling abolishing slavery in England, and the implication of what had occurred to the servant was a reaction to an illegal deportation. Day expanded Bicknell's draft, added footnote material on Africa, and played up the "nobleness" of the African depicted in the story.[9]

Influence

The poem ends on a note suggesting future African vengeance. It was influential on later abolitionist writers.[10] It has been suggested that The Negro Revenged, an illustration by Henry Fuseli to the poems of William Cowper, may also have been influenced by The Dying Negro.[11]

Notes

- 1 2 Marcus Wood (2003). The Poetry of Slavery: An Anglo-American Anthology, 1764–1865. Oxford University Press. p. 36. ISBN 978-0-19-818709-7.

- ↑ William L. Andrews; Henry Louis Gates (15 January 2000). Slave Narratives: Library of America #114. Library of America. p. 115. ISBN 978-1-59853-212-8.

- ↑ Erickson, Lee (2002). "'Unboastful Bard': Originally Anonymous English Romantic Poetry Book Publication, 1770-1835". New Literary History. 33 (2): 247–278. doi:10.1353/nlh.2002.0013. JSTOR 20057723. S2CID 161192445.

- ↑ McCann, Andrew (1996). "Conjugal Love and the Enlightenment Subject: The Colonial Context of Non-Identity in Maria Edgeworth's 'Belinda'". Novel: A Forum on Fiction. 30 (1): 56–77. doi:10.2307/1345847. JSTOR 1345847.

- ↑ Samuel Johnson in Context. Cambridge University Press. January 2012. p. 356. ISBN 978-0-521-19010-7.

- ↑ Edith Hall; Richard Alston; Justine McConnell (7 July 2011). Ancient Slavery and Abolition: From Hobbes to Hollywood. OUP Oxford. p. 131. ISBN 978-0-19-957467-4.

- ↑ Jack P. Greene (29 March 2013). Evaluating Empire and Confronting Colonialism in Eighteenth-Century Britain. Cambridge University Press. p. 187 note 79. ISBN 978-1-107-03055-8.

- ↑ Vincent Carretta (2011). Phillis Wheatley: Biography of a Genius in Bondage. University of Georgia Press. p. 129. ISBN 978-0-8203-3338-0.

- ↑ Rodgers, Nini (2000). "Two Quakers and a Utilitarian: The Reaction of Three Irish Women Writers to the Problem of Slavery 1789-1807". Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy. Section C: Archaeology, Celtic Studies, History, Linguistics, Literature. 100C (4): 137–157. JSTOR 25516261.

- ↑ James G. Basker (2002). Amazing Grace: An Anthology of Poems about Slavery, 1660–1810. Yale University Press. p. 203. ISBN 978-0-300-09172-4.

- ↑ Jean Vercoutter; Hugh Honour (1989). The Image of the Black in Western Art. Office du livre. p. 93.