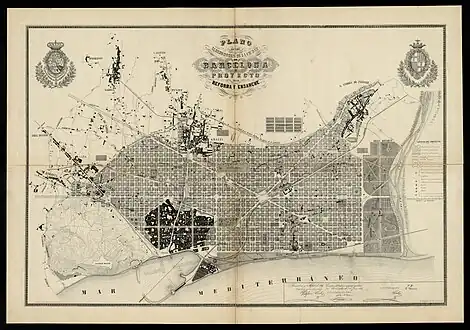

The Cerdà Plan was a plan to reform and expand the city of Barcelona created in 1860 that followed the criteria of the Hippodamus plan, with a grid structure, open and egalitarian. It was created by the civil engineer Ildefons Cerdà and its approval was followed by a strong controversy for having been imposed by the government of the Kingdom of Spain against the plan of Antonio Rovira y Trías who had won a competition of the Barcelona City Council.

The widening contemplated in the plan unfolded over an immense area that was free of buildings as it was considered a strategic military zone. It proposed a continuous grid of blocks of 113.3 meters from the Besós to Montjuic, with streets of 20, 30, and 60 meters with a maximum building height of 16 meters. The novelty in the application of the Hippodamus plan was that the blocks had 45º chamfers to allow better visibility.[1]

The development of the plan lasted almost a century. Throughout this time, the plan has been transformed and many of its guidelines were not applied. The original Cerdá plan was modified as a result of the interests of the land owners and speculation.

Historical background

Barcelona in the 19th century. Unhealthy and oppressed

Throughout the 18th century and the first part of the 19th century, the health and social situation of Barcelona's population had become suffocating. The medieval wall that had enabled the city to resist seven sieges between 1641 and 1714 now represented a brake on urban expansion. Population growth raised the population from 115,000 in 1802 to 140,000 in 1821 and reached 187,000 in 1850. The 6 km of walls surrounded an area of just over 2 km2, although 40% of the space was occupied by 7 barracks, 11 hospitals, 40 convents, and 27 churches.[2]

Sanitary conditions worsened as a result of the density and lack of sanitary infrastructures such as sewage systems or running water. Burials in cemeteries in front of churches were sources of infections, groundwater contamination , and epidemics. Despite the decision made by Bishop Pablo de Sichar[3] in 1819 to hold burials in the Pueblo Nuevo cemetery, its operation was not consolidated until the middle of the 19th century.[4] From that moment on, and forced by military ordinances, cemetery spaces began to be recovered at the doors of churches such as San Justo, San Pedro de las Puellas or the Fossar de les Moreres.[5]

In these circumstances, life expectancy was 36 years for the rich and 23 for the poor and day laborers.[2] Barcelona, like Catalonia, had been hit by the plague in the 15th and 16th centuries, and suffered several epidemics throughout the 19th century:

- 1821: yellow fever with 8,821 deaths (see: Cholera pandemics in Spain).

- 1834: cholera with 3,344 deaths.

- 1854: cholera with 6,419.

- 1865: cholera with 3,765.[6]

The military consideration of Barcelona as a stronghold with the Citadel next to it conditioned urban life. Not only were the problems of the citizens within the walls ignored, but the timid movements to expand outside the walls were repressed with the demolition of the buildings because they "prevented the defense of the city" as occurred in 1813,[7] since the area up to the distance of a cannon shot, which corresponded approximately to the "jardinets de Gràcia", was considered non-aedificanda (unbuilt area).[8]

The voices against it came not only from the citizens but also from the Barcelona City Council itself, which, through the "Junta de Ornato" (Beautification Board) and in harmony with Captain General Baron de Meer, in 1838 requested a modification of the wall between the door of the Studies (the Rambla) and the bastion of Jonqueres (Urquinaona square) to achieve a small extension.[6]

Down with the walls

In 1841 the Barcelona City Council announced a competition to promote the development of the city. On September 11, 1841, the prize was awarded to Dr. Pedro Felipe Monlau, doctor and hygienist, author of the work Abajo las murallas, Memoria acerca de las ventajas que reportaría a Barcelona y especialmente a su industria de la demolición de las murallas que circuyen la ciudad (Report on the advantages that the demolition of the walls surrounding the city would bring to Barcelona and especially to its industry), in which an expansion from the Llobregat River to the Besós is demanded.

The wide diffusion of the project and the popular impulse provoked confrontations such as the one on October 26, 1842, in which the Demolition Board demolished part of the Citadel, which caused General Espartero to bombard Barcelona from the castle of Montjuic on December 3, and ordered its reconstruction with an expense of 12 million reales at the expense of the city.[9]

In 1844, Jaime Balmes joined, from the pages of La Sociedad, the protests contradicting the theories of military strategic value defended by General Narváez.

More than ten years passed until the Barcelona City Council approved a project prepared by its secretary Manuel Durán y Bas, which was sent to the Madrid government on May 23, 1853, with the unanimous signature of the consistory with its mayor, Josep Beltran i Ros at the head. The report received the support of the Catalan deputies and especially Pascual Madoz, deputy for Lérida and a key person in the demolition of the walls. Madoz became civil governor of Barcelona for barely seventy-five days when he became Minister of Finance of the progressive government, from where he urged the disentailment and promulgated a royal order that would put an end to the confrontations between the City Council and the Ministry of War.[9] The order to demolish the walls of August 9, 1854, specified that the sea wall, Montjuic Castle, and the Citadel were to be maintained.[10]

The expansion project

The need for an expansion

The need to grow outside the walls was obvious, but we must also bear in mind the speculative effect that the urbanization of 1,100 hectares of land would have. With the competition opened by the city council in December 1840 and won by Monlau's "Abajo las Murallas" project, the period of transformation of the city began. In 1844 Miquel Garriga i Roca offered himself to the Barcelona City Council as municipal architect for the planning of the expansion, with a proposal focused on ornamental beautification operations. In 1846 Antonio Rovira y Trías published in the Boletín Enciclopédico de Nobles Artes a proposal for the formation of a geometric plan of Barcelona.[11]

The preparation of the Expansion Project

In 1853, a year before the demolition of the walls, the city council began to prepare for the next stage by creating the Commission of the Corporations of Barcelona. It later became the Commission of the Eixample; it included representatives of the industry, the architects Josep Vila Francisco Daniel Molina, Josep Oriol Mestres, José Fontseré Doménech, Joan Soler i Mestres, and representatives of the press: Jaume Badia, Antonio Brusi y Ferrer, Tomás Barraquer and Antonio Gayolá.[12]

In 1855, the Ministry of Public Works commissioned Cerdá to draw up the topographical plan of the Llano de Barcelona, which was the extensive area between Barcelona and Gracia and from Sants to San Andrés de Palomar that had not been urbanized for military reasons. Cerdá was a person very sensitive to the hygienist currents, he applied his knowledge to develop, on his own, a Monograph of the working class (1856), a complete and deep statistical analysis of the living conditions within the city walls based on social, and economic, and nutritional aspects. The diagnosis was clear: the city was not suitable for "the new civilization, characterized by the application of steam energy in industry and the improvement of mobility[13] and communication" (the optical telegraph was the other relevant invention).[14]

Aware of this deficiency, Cerdá began without any commission to structure his thinking, systematically exposed many years later (1867) in his great work: Teoría General de la Urbanización (General Theory of Urbanization). One of the most important features of Cerdá's proposal, what makes him stand out in the history of urban planning, is the search for coherence to account for the contradictory requirements of a complex agglomeration. He overcomes partial visions (utopian, cultural, monumental, rationalist city...) and goes in search of an integral city.[15]

The year 1859 was a crucial year for the expansion. On February 2, Cerdá received an order from the central government to verify the study for the expansion within twelve months. The city council reacted immediately by calling on April 15 a public competition on plans for the widening with a deadline of July 31, although it was postponed to August 15. Meanwhile, Cerdá wasted no time, finished his project, and showed it -to gain support in Madrid- to Madoz, Laureano Figuerola, and the general director of Public Works, the Marquis of Corvera. But June 9, 1859, is the date on which the central government finally approved the widening plan designed by Cerdá using a royal order. From that moment on, there were technical, political, and economic disputes between the central and municipal governments. Concerning the municipal competition, thirteen projects were presented, the unanimous winner was Antonio Rovira y Trías on October 10, 1859. Following a royal order of December 17, all of them plus that of Cerdá were exposed indicating the deserved qualification, the City Council refraining from evaluating that of Cerdá.

The issue was finally resolved on July 8, 1860, when the Ministry ordered the execution of the Cerdá Plan.[16]

Municipal contest

The projects submitted to the Barcelona City Council competition to design an expansion for the city focused, in most cases, its solution in the "road from Barcelona to Gracia" that for some time was being consolidated urbanistically as Passeig de Gracia and that conditioned the possible solutions. These plans, unlike the one proposed by Cerdá, occupied a smaller area and were intended to accommodate fewer people, which is logical if we think that they obeyed the objectives of the bourgeoisie to reinforce social segregation. Thus, the winning plan of the widening competition, presented by Rovira i Trias, corresponds to the slogan that headed it: "The layout of a city is more the work of time than of the architect"; and Rovira himself stated that the proletarians could not live in what "will have to be properly called the city of Barcelona".[17]

The projects were submitted under pseudonyms and the plaques of the non-awarded projects were destroyed, so part of the documentation has been lost.[18]

Major Projects

- Soler y Gloria Project: Francisco Soler Gloria's project, which won the first runner-up prize, proposed a grid development based on two axes: one following a line towards France parallel to the sea and the other towards Madrid along the old Sarriá road. The two converged in the walled city. He proposed an industrial district on the other side of the Montjuïc mountain, a precursor idea of today's Zona Franca. The connection of the old city with Gracia was proposed by making a new avenue starting from the current Plaza de la Universidad. His motto was: "E".

- Daniel Molina Project: No documentation of this project is preserved, except for the proposed solution for the Plaza de Cataluña. His motto was: "Hygiene, comfort, and beauty".

- Josep Fontserè Project: José Fontseré was a young architect, son of the municipal architect José Fontseré Doménech, and won the third runner-up prize with a project that enhanced the centrality of Passeig de Gràcia and linked the neighboring centers with a set of diagonals that respected their original plots. His motto was: "Do not destroy to build, but conserve to rectify and build to enlarge".

- Garriga i Roca Project: The municipal architect Miquel Garriga i Roca presented six projects. The best qualified responded to a grid solution that linked the city with Gracia, leaving only sketched lines that would have to continue developing the future plot. His motto was: "One more sacrifice to contribute to the Eixample of Barcelona".

- Other projects: The project of Josep Massanès and that of José María Planas proposed a mere extension while maintaining the wall around the new space. The latter had a similarity with the project presented by the "owners of the Paseo de Gracia" since both projects were based on a mere extension on both sides of the Paseo de Gracia. Two other simpler projects were that of Tomás Bertrán Soler, who proposed a new neighborhood in place of the Citadel, converting the Passeig de Sant Joan into an axis similar to the Rambla; and a very elementary one attributed to Francisco Soler Mestres, who died three days before the reading of the prizes.[19]

The Antoni Rovira project

According to the municipal council, the winning project was a proposal by Antoni Rovira based on a circular mesh that enveloped the walled city and grew radially, harmoniously integrating the surrounding villages. It was presented with the slogan: "Le tracé d'une ville est oeuvre du temps, plutôt que d'architecte".[20] The phrase is originally from Léonce Reynaud, an architectural reference of Rovira. It was structured in three areas where the different sectors of the population were combined with social activities with a logic of neighborhoods and hierarchy of space and public services. Based on a proposal to replace the wall, a mesh of rectangular blocks with a central courtyard and a height of 19 meters was deployed. A few main streets were the junction between blocks of the hippodamus structure to readjust the square profile to the semicircle that surrounded the city. Rovira proposes his solution with a clear center located in the Plaza de Cataluña, while Cerdá moved the centrality to the Plaza de la Glorias. The plan provided a solution for the Plaza de Cataluña, which was not foreseen in the Cerdá plan.[19]

Rovira's plot responds to a contemporary and residential expansion model like the "ring" of Vienna or the Haussmann project in Paris. This model was more aligned with the future capitalist "Großstadt" that would claim the Renaixença and the Lliga.[21]

The Cerdá Plan

After the unappealable approval of the central government, on September 4, 1860, Queen Isabella II laid the first stone of the Ensanche in the current Plaza de Cataluña. The growth of the city outside the walls was not rapid due to the lack of infrastructure and the distance from the city center.

In the 1870s there was remarkable progress as investors saw a great business opportunity. The return of the Indianos with the end of the colonies brought important capital that had to be invested and found in the widening of its best destination. The so-called gold rush began. But the great interest ended up being detrimental to the initial plan, and the construction fever contributed to the progressive reduction of green spaces and facilities. Finally, the four sides of the blocks were built.

The Exposición Universal (Universal Exposition) of 1888 meant a new impulse that allowed the renovation of some areas and the creation of public services. But it would be the great development of the late 19th century with the Modernism supported by the bourgeoisie that invested in buildings for rent, which would grow the Eixample in such a way that in 1897 Barcelona integrated the municipalities of Sants, Las Corts, San Gervasio de Cassolas, Gracia, San Andrés de Palomar, and San Martín de Provensals.[22]

The new language of Cerdá

The plan provided the primary classification of the territory: the "roads" and the "inter-road" spaces. The former constitute the public space for mobility, meeting, support for service networks (water, sanitation, gas...), trees (more than 100,000 street trees), lighting, and street furniture. The "intervías" (island, block, or square) are the spaces of private life, where multi-family buildings are gathered in two rows around an inner courtyard through which all dwellings (without exception) receive sunshine, natural light, ventilation, and joie de vivre, as demanded by the hygienist movements.

Cerdá defended the balance between urban values and rural advantages. "Ruralize that which is urban, urbanize that which is rural" is the message launched at the beginning of his General Theory of Urbanization.

In other words, its purpose was to give priority to "content" (people) over "container" (stones or gardens). The shape, such an obsessive theme in most plans, is but an instrument, albeit of the utmost importance, but often too decisive and sometimes overbearing. Cerdá's magic consists of conceiving the city from the home. The intimacy of the home is considered an absolute priority and, in a time of large families (three generations), to make possible the freedom of all members could be considered utopian.

Cerdá believes that the ideal dwelling is the isolated, the rural. However, the enormous advantages of the city force to compact, the essence of the urban fact, and to design a house that allows it to fit in a multi-family building in height, and enjoy, thanks to careful distribution, double ventilation from the street, and the inner courtyard of the "block". The presence of the sun is assured in all cases.[14]

Structure of the Cerdá Plan

In the plan proposed by Cerdá for the city, the optimism and unlimited foresight of growth, the programmed absence of a privileged center, and its mathematical, geometric character and scientific vision stand out.[15] Obsessed by the hygienist aspects that he had studied in depth and having wide freedom to configure the city since the plain of Barcelona had almost no construction, his structure takes maximum advantage of the direction of the winds to facilitate oxygenation and cleaning of the atmosphere.[23] Along the same line, he assigned a key role to the parks and interior gardens of the blocks, although later speculation greatly altered this plan. He fixed the location of trees in the streets (1 every 8 meters) and chose the shade plane tree to populate the city after analyzing which species would be the most suitable for living in the city.

In addition to the hygienic aspects, Cerdá was concerned about mobility. He defined an unusual width of streets, partly to escape from the inhuman density that the city lived, but also thinking of a motorized future with its own spaces separated from those of social coexistence that reserved them for the interior areas.[24]

He incorporated the layout of railway lines that had influenced his vision of the future when he visited France, although he is aware that these have to go underground, and he was concerned that each neighborhood should have an area dedicated to public buildings.[15] In this sense, he includes the advances within his progressive ideology when he stated:[23]

...when railways have become generalized, all European nations will be one city, and all families, only one, and their forms of government will be the same. Cerdà, 1851

The most outstanding formal solution of the project was the incorporation of the block; its crucial and singular form concerning other European cities is marked by its square structure of 113.33 meters with 45º chamfers.[15]

The geometry of the expansion (Ensanche)

Cerdá's hippodamus grid provided for streets 20, 30, and 60 meters wide. The blocks had construction on only two of the four sides, giving a density of 800,000 people. With the original design, the expansion would have been fully occupied by 1900,[25] although both Cerdá himself and, later, some speculative actions substantially densified it.

Cerdà proposed the "Ensanche ilimitado" (unlimited expansion) a regular and unperturbed grid along the entire urban layout. Unlike other proposals that broke its repetitive rhythm to put green spaces or services, Cerdà's proposal encompasses them internally and allowed to set a continuous repetition in the plan with the ability to alter it when appropriate.[19]

The egalitarian principle that Cerdà wanted to imprint in his urban planning justifies this homogeneity in search of equality, not only between social classes, but also for the convenience of the traffic of people and vehicles, since whether one circulates along a road as if it is done by its transversals, the crossings between them are at the same distance, and in the absence of some roads more comfortable than others, the value of habitats will tend to be equalized.[1]

The engineer's vision was of growth and modernity; his genius allowed him to anticipate future urban traffic conflicts 30 years before the invention of the automobile.[23]

Regarding the orientation, the roads run parallel to the sea, some of them, and perpendicular, others, so that the orientation of the vertices of the squares coincide with the cardinal points and therefore all sides have direct sunlight throughout the day, denoting once again the importance that the designer attaches to the solar phenomenon.

Cerdá deployed the layout on the spine of the Gran Vía. He works with modules of 10 x 10 "blocks" (which Cerdá considered a district) and which correspond to the main crossroads (Plaza de la Glorias Catalanas; Plaza Tetuán; Plaza Universidad), with a wider street every 5 (Calle Marina; Vía Layetana that would cross the old city 50 years later; Calle Urgell). With these proportions, as well as the resulting "block" size, Cerdá managed to place one of the wide streets leading down from the mountain to the sea on each side of the old city (Urgell and Sant Joan) with 15 blocks in between.

The streets are generally 20 meters wide, of which at present the central 10 meters are destined for the roadway and 5 meters on each side for sidewalks. The width of the streets, as in the Parisian model of Haussmann, is associated with a military vision to suppress internal uprisings. We recall that Cerdá had experienced firsthand the workers' revolts of 1855. The praise that the plan received from his contemporaries was to consider the rectilinear format as advantageous for artillery fire.

Exceptions to regularity

The Ensanche ilimitado (unlimited expansion) of the city showed little sensitivity to the integration of the urban fabric of the peripheral villages. The links with these nuclei were not foreseen, except for San Andrés de Palomar, bordered by Meridiana Avenue, and the canals of human tradition were ignored. In 1907 the City Council approved the Jaussely Plan, a plan of links to solve these deficiencies. Some of the criteria included in this plan and the maintenance of the use of some roads during the development of the Cerdá plan have prevented their disappearance. Pere IV Street (the old road to France), Mistral Avenue (the old road to Sants and linking with Carmen Street in the walled city), Roma Avenue (old road to Las Corts) or Gracia crossroads (the old Roman road), are some examples.[26]

Special mention deserves the design of Paseo de Gracia and Rambla de Cataluña, where to respect the old road of Gracia and the natural slope of the waters, hence the name Rambla, Cerdá traced only two consecutive roads of special width where in reality attending to the layout of 113, In addition, the Paseo de Gracia, to respect the old layout, is not exactly parallel in the rest of the streets, which means that the existing blocks between the two aforementioned roads, although they have an orthogonal design with chamfers, present irregularities that give them the shape of trapezoids.

To all this, we must add the presence of some of special characters that do not follow the grid layout but cross it diagonally, such as the Diagonal Avenue itself, the Meridiana Avenue, the Parallel, and others that were designed respecting the existence of ancient communication routes with neighboring towns.

Geometry of blocks

The dimensions of the blocks are given by the aforementioned distances between the longitudinal axes of the streets and the same width of these roads, so that by establishing a standard width of 20 meters, the blocks are formed by quadrilaterals of 113.3 meters, their vertices truncated in the form of a chamfer of 15 meters, which gives a block area of 1.24 hectares, contrary to popular belief that they have an exact area of 1 hectare. The figure of 113.3 meters has had various justifications. Manuel de Solà-Morales considers that the 5 blocks between the old bastion of Tallers (now Plaça Universitat) and that of Jonqueres (now Plaça Urquinaona) are the ones that mark the factor from which the rest is built.[27]

Cerdà justified the chamfering of the vertexes of the blocks from the point of view of the visibility that this gives to road traffic and in a vision of the future in which he was not more mistaken than in the term used to define the vehicle, he spoke of the private locomotives that one day would circulate through the streets and the need to create a wider space at each intersection to favor the stopping of these locomotives.

The first generalization of the use of the chamfer or ochava was given throughout Argentina as a result of the decree of the Minister of Government and later President Bernardino Rivadavia "Edificios y calles de las ciudades y pueblos" ("Buildings and streets of cities and towns") of December 14, 1821. Almost 4 decades later it became generalized for the first time in Spain thanks to Ildefonso Cerdá, who had studied the case of Buenos Aires and its chamfers for the writing of his work "Teoría de la construcción de las ciudades, vol. 1" (Theory of the construction of cities, vol. 1). Barcelona, 1859[28] and replicates it in his planimetric design for Barcelona (1856), known as The Cerdá Plan, where the chamfers are as long as the conventional streets are wide (20 meters), to allow vehicles to turn without sharp turns, as they go from having to turn at right angles to obtuse ones. In addition, it allowed better visibility of adjacent roads, and had the added advantage of relieving traffic at intersections by giving them an additional surface area. The chamfer was copied by other Spanish urban extensions, becoming widespread in the Iberian Peninsula.

The design of some wider tracks, without disturbing the regular 113.3 m grid, makes it possible to adequately reduce the dimensions of the blocks affected by the widening of the tracks, as is the case of Gran Vía de las Cortes Catalanas, under which the metro and train circulate, Aragón Street, where for many years the railroad ran in the open air until it was finally buried, Urgell Street and others.

Within the space of each block, Cerdá conceived two basic forms to locate the buildings, one presented two parallel blocks located on opposite sides, leaving inside a large rectangular space for the garden and the other presented two blocks joined in an "L" shape located on two adjacent sides of the block, leaving in the rest a large square space also for the garden.

The succession of blocks of the first type resulted in a large longitudinal garden that crossed the streets and the grouping of 4 blocks of the second type, conveniently arranged, forming a large built square crossed by two perpendicular streets and with its four gardens united in one.

The non-acceptance of the Cerdá plan

Already before its approval, it was opposed by municipalists more for what it represented (the imposition from Madrid) than for its content. The Barcelona elites acted against the plan in the same way they were acting against the growing popular protests. The anti-authoritarian, anti-hierarchical, egalitarian[29] and rationalist character of the plan clashed directly with the vision of the bourgeoisie who preferred to have Paris or Washington as a reference for a new city with a more particularist architecture. The figure of Cerdá also generated antipathy among architects who could not forgive him for the confrontation that had involved assigning urban planning responsibility to an engineer. Cerdá suffered a personal smear campaign full of legends and lies. It was of no use that he was from a Catalan family originating in the 15th century, nor that he had proclaimed the Catalan federal republic from the balcony of the Generalitat de Catalunya, for it to be spread that he was "not Catalan". Domènech i Montaner claimed that the width of the streets would produce drafts that would prevent a comfortable life. To cope with this, he distributed the pavilions of his Hospital de San Pablo in the opposite direction to the alignment of the street.[30]

In 1905, 50 years after the approval of the plan, Prat de la Riba expressed his deep indignation "against the governments that imposed on us the monotonous and shameful grid" instead of the system he dreamed of a city radiated from the old historical capital.[29]

Evolution of the Cerdá Plan

The structure of the blocks

The opposition to Cerdá and his Plan by the people of Barcelona facilitated the emergence of speculative activities and arguments that tried to get more built space. The first of them was that if the streets were 20 meters wide, it could well increase the depth of the buildings to the same extent, the central area of the blocks was subsequently occupied with low buildings, destined in most cases to workshops and small family industries, thus disappearing most of the central gardens, so that as a last resort to increase the built land, the two sides already built were joined with buildings that joined them, completely closing the blocks.

Evolution of the building´s height. The "ski lifts"

It seemed that at this point the speculative process ended, but a new argument appeared: if the streets were 20 meters wide, there should be no inconvenience for the buildings to have a height of 20 m instead of the projected 16 m, since the increase in height, with the sun at 45º, illuminates any building in its entirety without any neighboring building casting a shadow; this argument, together with the construction of lower ceilings, resulted in a gain of two stories in height.

Finally, taking into account the previous theory, if an additional floor is built on top of the current building, but with the façade set back towards the interior of the building by the same amount as the height of this floor, it would increase the built space without the shadow of the building affecting the neighboring buildings if the sun is at 45º; thus the attic floor was born, and by the same theory the attic floor was built, with the façade set back again by the same amount as the height of this new floor.

See also

References

- 1 2 Permanyer, Lluís (15 June 2023), L'Eixample, 150 anys d'Història. (in Spanish), Viena Edicions i Ajuntament de Barcelona, ISBN 978-84-9850-131-5, retrieved 26 June 2023

- 1 2 Permanyer, Lluís (15 June 2023), L'Eixample, 150 anys d'Història (in Spanish), Viena Edicions i Ajuntament de Barcelona, ISBN 978-84-9850-131-5, retrieved 26 June 2023

- ↑ The cemetery of Pueblo Nuevo had been built by Bishop Climent in 1719, although it was unsuccessful due to its remoteness from the city and was finally destroyed during the French War. It was after its reconstruction, in 1819, when it began to function with a progressive normality.

- ↑ Revista Icària (2008). "Pueblo Nuevo Historical Archives". Pueblo Nuevo Historical Archives (in Spanish). 13: 13–18.

- ↑ Huertas Claveria, Josep Maria i Fabre, Jaume (15 June 2023), Burgesa i revolucionària: la Barcelona del segle XX. (in Spanish), Flor del Vent, retrieved 26 June 2023

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - 1 2 Permanyer, Lluís (15 June 2023), L'Eixample, 150 anys d'Història. (in Spanish), Viena Edicions i Ajuntament de Barcelona, ISBN 978-84-9850-131-5, retrieved 27 June 2023

- ↑ Garcia Espuche, Albert. Una ciudad estancada». Espacio y Sociedad en la Barcelona preindustrial (in Spanish).

- ↑ "L'Eixample, 150 anys d'Història.", Viena Edicions i Ajuntament de Barcelona (in Spanish), 15 June 2023, retrieved 27 June 2023

- 1 2 "Arxiu Històric | de Barcelona". ajuntament.barcelona.cat. Retrieved 27 June 2023.

- ↑ "L'Eixample, 150 anys d'Història", Barcelona: Viena Edicions i Ajuntament de Barcelona (in Spanish), 15 June 2023, retrieved 27 June 2023

- ↑ Babiano i Sànchez, Eloi (15 June 2023), "Antoni Rovira i Trias, Arquitecte de Barcelona", Barcelona: Viena Edicions i Ajuntament de Barcelona (in Spanish), retrieved 27 June 2023

- ↑ Babiano i Sànchez, Eloi (15 June 2023), Antoni Rovira i Trias, Arquitecte de Barcelona (in Spanish), Viena Edicions i Ajuntament de Barcelona, ISBN 978-84-9850-071-4, retrieved 27 June 2023

- ↑ Babiano i Sànchez, Eloi (3 September 2021), Antoni Rovira i Trias, Arquitecte de Barcelona. (in Spanish), Viena Edicions i Ajuntament de Barcelona, ISBN 978-84-9850-071-4, retrieved 27 June 2023

- 1 2 "Cerdá" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 October 2009. Retrieved 27 June 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 Montaner, Josep Maria (1978). Ildefonso Cerda and Modern Barcelona (in Spanish) (3 ed.). Revista Catalonia Cultura. pp. 44–45.

- ↑ Babiano i Sànchez, Elio (15 June 2023), "Antoni Rovira i Trias, Arquitecte de Barcelona.", Viena Edicions i Ajuntament de Barcelona (in Spanish), retrieved 27 June 2023

- ↑ Torrent, Joaquim (2007). Ildefons Cerdà, un gran visionario y precursor (in Spanish). NacioDigital.cat.

- ↑ Cerdà, Oficina Coordinació Any. "El web de l'Any Cerdà". www.anycerda.org (in Catalan). Retrieved 28 June 2023.

- 1 2 3 Babiano i Sànchez, Eloi (15 June 2023), Antoni Rovira i Trias, Arquitecte de Barcelona (in Spanish), Ajuntament de Barcelona, ISBN 978-84-9850-071-4, retrieved 28 June 2023

- ↑ The layout of a city is the work of time rather than of the architect.

- ↑ Babiano i Sànchez, Eloi (16 January 2022), Antoni Rovira i Trias, Arquitecte de Barcelona (in Spanish), Viena Edicions i Ajuntament de Barcelona, ISBN 978-84-9850-071-4, retrieved 28 June 2023

- ↑ Cerdà, Oficina Coordinació Any. "El web de l'Any Cerdà". www.anycerda.org (in Catalan). Retrieved 28 June 2023.

- 1 2 3 Navarro, Nuria (2009). El inventor de Barcelona. 150 años del Eixample (in Spanish). Periódico-Quadern.

- ↑ Bohigas, Oriol (1958). "En el centenario de Cerdà". Cuadernos de Arquitectura (in Spanish): 7–13.

- ↑ Bohigas, Oriol (15 June 2023), "Barcelona entre el pla Cerdà i el barraquisme", Cuadernos de arquitectura (in Spanish), p. 34, retrieved 28 June 2023

- ↑ Bohigas, Oriol (15 June 2023), "Barcelona entre el pla Cerdà i el barraquisme", Cuadernos de arquitectura (in Spanish), retrieved 29 June 2023

- ↑ Solà-Morales, Manuel. Cerdá Year Opening Speech.

- ↑ Busquets, Joanl (2009). Barcelona Metropolis. The reason in the city: the Cerdá Plan (PDF) (in Spanish). Revista de información y pensamiento urbano.

- 1 2 Cirici-Pellicer, Alexandre (1959). Significación del Plan Cerdá (in Spanish). Cuadernos de arquitectura.

- ↑ Permanyer, Lluís (2009). El fracasado monumento a Cerdá (in Spanish). La Vanguardia.

Bibliography

- Permanyer, Lluís (2008). L'Eixample, 150 anys d'Història. Barcelona: Viena Edicions i Ajuntament de Barcelona.

- Babiano i Sànchez, Eloi (2007). Antoni Rovira i Trias, Arquitecte de Barcelona. Barcelona: Viena Edicions i Ajuntament de Barcelona.

- Huertas Claveria, Josep Maria i Fabre, Jaume (2000). Burgesa i revolucionària: la Barcelona del segle XX. Barcelona: Flor del Vent.

- Bohigas,Oriol (1963). Barcelona entre el pla Cerdà i el barraquisme. Barcelona: Edicions 62.

- Santa-Maria, Glòria (2009). Decidir la ciutat futura. Barcelona 1859. Barcelona: Ayuntamiento de Barcelona