The Texas Folklore Society is a non-profit organization formed on December 29, 1909, in Dallas, Texas.[1] According to John Avery Lomax, the first print collection included "public songs and ballads; superstitions, signs and omens, cures and peculiar customs; legends; dialects; games, plays and dances; fiddles and proverbs."[1] Their mission statement is "The Texas Folklore Society collects, preserves, and shares the practices and customs of the people of Texas and the Southwest."[2]

Academics John Avery Lomax and Dr. Leonidas Warren Payne, Jr. served as its first officers, with the latter becoming the organization's first president and the former becoming the first secretary.[1] The following individuals were secretaries: Judd Mortimer Lewis, Edward Rotan, and Lillie T. Shaver. The treasurer was Miss Ethel Hibbs.[1] The counselors were Theo G. Lemmon, Joseph B. Dibrell, and C.C. Garret.[1]

History

Following the initial membership, by 1944, several other charters emerged at institutions including the University of California, University of Texas, and Rice Institute.[1] The Society's annual meetings have been held regularly since 1911, except for interruptions caused by the two world wars.[1] Since 1923, the Society's publications became edited by the Secretary-Editor, J. Franke Dobie, who also attends its day-to-day business.[1] Also, within that year, the organization has published or sponsored at least one volume per year.[1] The group had headquarters in Austin, Texas, until 1971.[1] Once Francis Edward Abernethy became the Secretary-Editor, the Texas Folklore Society moved its offices to the campus of Stephen F. Austin State University in Nacogdoches.[1]

Membership

Membership is open to all people interested in folklore. Editor J. Franke Dobie stated, "This is the only organization that you join and attend because you want to. You expect no professional advancements from it; you have no political axe to grind. You are not pressured to become a member or read a paper. You belong because you want to. That is the very nature of the Society, one thing that distinguishes it from any other".[3]

Current member benefits include folklore books selected for distribution and a 20% discount on purchases of most books from Texas A&M University Press. Members may also share folklore through presentations and meetings, present papers at the annual meeting, submit folklore papers for publication in the annual volume, present papers, participate in webinars, and hear new audio recordings of papers.

Prominent members

The Texas Folklore society has enjoyed the membership of a variety of cultures and backgrounds.[4] The first African-American member of Texas Folklore Society was J. Mason Brewer who published several works in the folklore and poetry genre including The Word on the Brazos (1953), Aunt Dicey Tales (1956), Dog Ghosts and Other Texas Negro Folk Tales (1958), and Worser Days and Better Times (1965).[5] American folklorist and educator Jovita González was also involved in the Texas Folklore Society. With J. Frank Dobie endorsing her election, González became the first Mexican-American and female member to become vice president in 1928, and president for two terms from 1930 to 1932.[6] Other prominent members include: Kenneth Davis, also a fellow with the West Texas Historical Association; B W Aston, a former member of the Hardin-Simmons University faculty in Abilene; and Paul Patterson, the western author, and mentor of novelist Elmer Kelton.

Publications

I Was Here When the Woods Were Burnt

"I Was Here When the Woods Were Burnt" is the first publication of the Texas Folklore Society.[7] This account appears in a 1946 TFS sheet and the 1925 reprint of Happy Hunting Ground.[8] Happy Hunting Ground is a "collection of popular folklore from Central and South America, including Mexican ballads, primitive art, cowboy dances, reptile myths, superstitions, Indian pictographs, and other folktales."[9] The piece was originally a speech given during the twenty-fifth anniversary of the organization in April 20, 1934 by then President Leonidas Warren Payne.[10] This piece's presentation at the Founders' Day dinner in the Union Building at the University of Texas marked the perseverance and accomplishments of the Society.[10] In the speech, Payne narrates the inception of the Texas Folklore Society, which began as a conversation between himself and John Avery Lomax in 1909, after a Thanksgiving collegiate football game.[11] Interestingly, he uses racially charged language to detail the brilliance of their plan by comparing themselves to African-American children. In reference he states, "I think the case is somewhat similar to that of the two little darkies sitting snuggled up to each other... One said to the other, 'Who's sweet?' and the other replied, 'Bofe uv us!'.[11] Thus, they regarded themselves as elite, white, and intelligent subjects--thus, these became the very individuals they sought after to join the Society. Afterwards, they determined academia to be the necessary elite space to gather folklorist whom document Texas culture they proceeded to draft a charter for the organization.[11] All in all, the speech's symbolism placed Payne at the origin of the Society, thus firmly founding its prosperity.[12] This speech reflects the lack of diversity in membership, as many proceeding publications depicted racial stereotypes. Yet, in response to these claims, editor J. Franke Dobie stated, "It is none of the editors business".[12] Despite TFS writers becoming the "most educated and sophisticated people of their time and culture"[12] they knowingly distributed accounts that justified the racial hierarchy.

Indian Pictographs Near Lange's Mill, Gillespie County, Texas

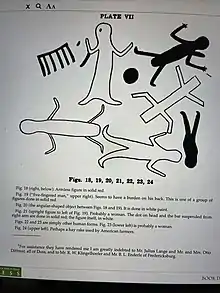

Amanda Julia Estill (1882–1965) was a white Texas-American teacher who served as a member and eventually became the president of TFS in 1923.[13][14] Estill was one of the first members to publish information regarding Native American culture in Gillespie County.[14] In this piece, as published in the 1925 collection history entitled, Happy, Hunting Ground, she recounts the combative history between Native American Comanches and neighboring whites with Gillespie County.[8] In doing so, she historicizes the pioneering efforts of Julius Lange, a German Mill owner. Estill collects his stories describing bouts with "savage Indians" who would "capture or kill... pretty pioneer maidens with long flowing hair".[8] While Estill highlights several instances in which Native peoples appear to attack several white families, she also discusses Native American weaponry and writings in grave detail. For example, she mentions how indigenous subjects would dip arrows in the poison from venomous snakes to ensure the fatality of their victims when pierced.[8] Within the concluding pages, Estill includes several reiterations of what she calls Native American "scribe".[8] As depicted in figure one, nearly all of her characterizations represent Native Americans harming white subjects. Estill's writings serve to distribute racial stereotypes amongst broad audiences by solely depicting the perspective of while settler colonials, a negative attribute often seen in the folklore genre.[15]

A Biscuit For Your Shoe; A Memoir Of County Line, A Texas Freedom Colony

Beatrice Upshaw is an African-American Texas Folklore Society member, whose other careers include being a performer, therapist, and Bible study instructor.[16] In 2020, Beatrice Upshaw published this account historicizing the African American community located in the Texas Freedom Colony, Upshaw, located near Nacogdoches.[17] In doing so, she utilizes this memoir to record her family's culture, beliefs, historic games, and more.[18] Upshaw notes how race played an important factor in how she was raised and socialized. She remembers playing within the bounds of the segregated 'Black Jack Cemetery,' where black individuals were not allowed to become buried on the premises.[17] Even within her childhood, Upshaw fully recognized racial boundaries and the Southern customs. Throughout her narrative, she depicts how these attributes shaped the culture and identity of the black Upshaw community. This narrative represents the shift in perspectives that are currently marks the folklore genre. While it took a century to fully include black authors in TFS, the African American authors are still marked by respectability politics and occasionally engage in the stereotyping of urban versus rural African-Americans. While discussing the Upshaw community, Upshaw states the following, "There were no evils then, not in our corner of the universe...Far and away from us was the worry of drive-by shootings, drug busts, robberies, and murders...We were innocent, naive, country folks who largely made up the backbone of the nation—then."[19] While African-Americans have made strides in diversifying TFS, they still have limitations. Alas, often folklorists are not connected to the peoples that they seek to study. However, new authors blaze trails for folklore writers to become not just cultural advocates but activists.[20]

Other works

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Abernethy, Francis Edward; Satterwhite, Carolyn Fiedler (1992). Texas Folklore Society: 1909-1943. University of North Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-929398-42-6.

- ↑ "Mission". Texas Folklore Society.

- ↑ "Why Join". Texas Folklore Society. Retrieved 2021-04-27.

- ↑ http://www.texasfolkloresociety.org/inc/files/editor/files/Presidents.pdf

- ↑ Brewer, John Mason (2016). J. Mason Brewer, Folklorist and Scholar: His Early Texas Writings. Stephen F. Austin State University Press. ISBN 978-1-62288-134-5.

- ↑ "Jovita González", Wikipedia, 2021-03-20, retrieved 2021-04-27

- ↑ Project Muse (2019). "Happy Hunting Ground". Project Muse.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Happy Hunting Ground | University of North Texas Press ~ J. Frank Dobie, ed. | Preview". flexpub.com. Retrieved 2021-04-27.

- ↑ "The Portal to Texas History". The Portal to Texas History. Retrieved 2021-05-10.

- 1 2 Abernethy, Francis Edward; Satterwhite, Carolyn Fiedler (1992). Texas Folklore Society: 1909-1943. University of North Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-929398-42-6.

- 1 2 3 Abernethy, Francis Edward; Satterwhite, Carolyn Fiedler (1992). Texas Folklore Society: 1909-1943. University of North Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-929398-42-6.

- 1 2 3 Abernethy, Francis Edward; Satterwhite, Carolyn Fiedler (1992). Texas Folklore Society: 1909-1943. University of North Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-929398-42-6.

- ↑ "Amanda Julia Estill (1882-1965) - Find A Grave..." www.findagrave.com. Retrieved 2021-05-10.

- 1 2 "TSHA | Estill, Amanda Julia". www.tshaonline.org. Retrieved 2021-05-10.

- ↑ Jordan, Rosan A., and F. A. De Caro. “Women and the Study of Folklore.” Signs, vol. 11, no. 3, 1986, pp. 500–518. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3174007. Accessed 27 Apr. 2021.

- ↑ Newsroom, TSU. "Tarleton, Texas Folklore Society announce book release". Stephenville Empire-Tribune. Retrieved 2021-05-10.

- 1 2 Upshaw, Beatrice; Orton, Richard (2020-11-13). A Biscuit for Your Shoe: A Memoir of County Line, a Texas Freedom Colony. University of North Texas Press. ISBN 978-1-57441-821-7.

- 1 2 3 4 "Publications Of The Texas Folklore Society". Texas Folklore Society. Retrieved 2021-04-27.

- ↑ "Upshaw Book Signing in East Texas". Texas Folklore Society. Retrieved 2021-05-10.

- ↑ Zeitlin, Steven J. “I'm a Folklorist and You're Not: Expansive versus Delimited Strategies in the Practice of Folklore.” The Journal of American Folklore, vol. 113, no. 447, 2000, pp. 3–19. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/541263. Accessed 27 Apr. 2021.