A terrella (Latin for "little earth") is a small magnetised model ball representing the Earth, that is thought to have been invented by the English physician William Gilbert while investigating magnetism, and further developed 300 years later by the Norwegian scientist and explorer Kristian Birkeland, while investigating the aurora.

Terrellas have been used until the late 20th century to attempt to simulate the Earth's magnetosphere, but have now been replaced by computer simulations.

William Gilbert's terrella

William Gilbert, the royal physician to Queen Elizabeth I, devoted much of his time, energy and resources to the study of the Earth's magnetism. It had been known for centuries that a freely suspended compass needle pointed north. Earlier investigators (including Christopher Columbus) found that direction deviated somewhat from true north, and Robert Norman showed the force on the needle was not horizontal but slanted into the Earth.

William Gilbert's explanation was that the Earth itself was a giant magnet, and he demonstrated this by creating a scale model of the magnetic Earth, a "terrella", a sphere formed out of a lodestone. Passing a small compass over the terrella, Gilbert demonstrated that a horizontal compass would point towards the magnetic pole, while a dip needle, balanced on a horizontal axis perpendicular to the magnetic one, indicated the proper "magnetic inclination" between the magnetic force and the horizontal direction. Gilbert later reported his findings in De Magnete, Magneticisque Corporibus, et de Magno Magnete Tellure, published in 1600.

Kristian Birkeland's terrella

Kristian Birkeland was a Norwegian physicist who, around 1895, tried to explain why the lights of the polar aurora appeared only in regions centered at the magnetic poles.

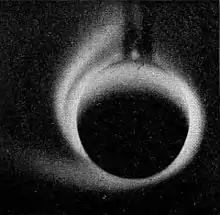

He simulated the effect by directing cathode rays (later identified as electrons) at a terrella in a vacuum tank, and found they indeed produced a glow in regions around the poles of the terrella. Because of residual gas in the chamber, the glow also outlined the path of the particles. Neither he nor his associate Carl Størmer (who calculated such paths) could understand why the actual aurora avoided the area directly above the poles themselves. Birkeland believed the electrons came from the Sun, since large auroral outbursts were associated with sunspot activity.

Birkeland constructed several terrellas. One large terrella experiment was reconstructed in Tromsø, Norway.[2]

Other terrellas

The German Baron Carl Reichenbach (1788–1869) also experimented with a terrella. He used an electromagnet, placed within a large hollow iron sphere, and this was examined in the darkroom under varying degrees of electrification.

Brunberg and Dattner in Sweden, around 1950, used a terrella to simulate trajectories of particles in the Earth's field. Podgorny in the Soviet Union, around 1972, built terrellas at which a flow of plasma was directed, simulating the solar wind. Hafiz-Ur Rahman at the University of California, Riverside conducted more realistic experiments around 1990. All such experiments are difficult to interpret, and are never able to scale all the parameters needed to properly simulate the Earth's magnetosphere, which is why such experiments have now been completely replaced by computer simulations.

Recently the terrella experiments have been further developed by a team of physicists at the Institute of Planetology and Astrophysics in Grenoble, France to create the "planeterrella" which uses two magnetised spheres which can be manipulated to recreate several different auroral phenomena.[3]

Notes

- ↑ Section 2, Chapter VI, page 678

References

- 1 2 Birkeland, Kristian (1908–1913). The Norwegian Aurora Polaris Expedition 1902-1903. New York and Christiania (now Oslo): H. Aschehoug & Co. out-of-print, full text online

- ↑ Terje Brundtland. "The Birkeland Terrella". Sphæra (7). Retrieved 24 May 2012.

- ↑ "Planeteterrella - English".