| "Summer in the City" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

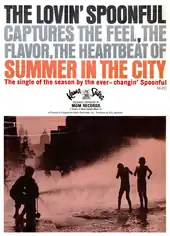

U.S. picture sleeve | ||||

| Single by the Lovin' Spoonful | ||||

| B-side | "Butchie's Tune" | |||

| Released | July 4, 1966 | |||

| Recorded | March 1966 | |||

| Studio | Columbia 7th Avenue, New York City | |||

| Genre | ||||

| Length | 2:39 | |||

| Label | Kama Sutra | |||

| Songwriter(s) | John Sebastian, Mark Sebastian, Steve Boone | |||

| Producer(s) | Erik Jacobsen | |||

| The Lovin' Spoonful singles chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Licensed audio | ||||

| "Summer in the City" on YouTube | ||||

"Summer in the City" is a song by the American folk-rock band the Lovin' Spoonful. Written by John Sebastian, Mark Sebastian and Steve Boone, the song was released as a non-album single in July 1966 and was included on the album Hums of the Lovin' Spoonful later that year. The single was the Lovin' Spoonful's fifth to break the top ten in the United States and their only to reach number one. A departure from the band's lighter sound, the recording features a harder rock style. The lyrics differ from most songs about the summer by lamenting the heat, contrasting the unpleasant warmth and noise of the daytime with the relief offered by the cool night, which allows for the nightlife to begin.

John Sebastian reworked the lyrics and melody of "Summer in the City" from a song written by his teenage brother Mark. Boone contributed the song's bridge while in the studio. The Lovin' Spoonful recorded "Summer in the City" in two sessions at Columbia Records' 7th Avenue Studio in New York in March 1966. Erik Jacobsen produced the sessions with assistance from engineer Roy Halee, while Artie Schroeck performed as a session musician on a Wurlitzer electric piano. The recording is an early instance in pop music of added sound effects, made up of car horns and a pneumatic drill to mimic city noises.

"Summer in the City" has since received praise from several music critics and musicologists for its changing major-minor keys and its inventive use of sound effects. The song has been covered by several artists, including Quincy Jones, whose 1973 version won the Grammy Award for Best Instrumental Arrangement and has since been sampled by numerous hip hop artists.

Background and composition

The Lovin' Spoonful completed their first two albums, Do You Believe in Magic and Daydream, over a period of six months. In need of new material for their next LP, John Sebastian, the band's principal songwriter, recalled a song composed and informally taped by his teenage brother, Mark,[6] titled "It's a Different World".[7][note 1] Written when Mark was 14,[8] it featured a bossa nova-like sound and rudimentary lyrics,[7] written in the style of soul singer Sam Cooke.[9]

[My brother] Mark really was the beginning of the song. Hot town, summer in the city ... but at night it's a different world. "Hey, hold on, what's that?" I said.[8]

– John Sebastian, 2018

John expanded on Mark's original composition,[7] reworking the melody and "[replacing] Mark's laconic verses with more vital, upbeat ones."[10] John was pleased with Mark's original line, "But at night it's a different world", determining that the verse before that point needed to build up tension toward an eventual release:[11] "I was going for the scary, minor chord, hit-the-road-Jack chord sequence that doesn't warn you of what's coming in the chorus."[9] He later compared his resulting first verse to the tension established in Modest Mussorgsky's Night on Bald Mountain, which he knew from the 1940 film Fantasia.[11] He incorporated into the verse a riff session player Artie Schroeck had played between takes during their sessions for the What's Up, Tiger Lily? soundtrack.[7] While recording the song, the band determined that a bridge or middle eight was needed to complement John's "tense" and "free-swinging" parts, prompting bassist Steve Boone to suggest a "jazzy figure", a "piano interlude" which he later said "sounded a little bit like [American pianist] George Gershwin".[12]

Lyrics and music

While most songs about summer romanticize warm weather, the lyrics of "Summer in the City" lament the heat of the daytime.[13] The combined unpleasantness of the daytime heat and noise are directly contrasted with the relief offered by nighttime, whose cooler temperatures allow for city nightlife to begin, consisting in dancing and finding dates. Sadness returns again when the singer complains that the days in the city cannot be like the nights.[3]

The song opens with two descending notes (a flattened or minor sixth followed by a perfect fifth degree of a minor scale) played three times.[14] This intro is played in octaves by the lead guitar, bass and electric piano. On the fourth beat of each bar, a snare and bass drum smash.[15] While the two note descent establishes the song in a minor mode, the verse suggests a Dorian mode. The vocal of the verse is entirely minor-pentatonic. John's arpeggiation on the major V (heard at "[5] all around, [7] people lookin' [2] half dead", as noted by Everett) confirms the mode is minor before immediately shifting back to major when his voice is joined in harmony (heard at "hotter than a matchhead").[14]

In contrast to the verse, the next section, which Everett writes "ought to be called the bridge", is a major mode, suggestive of the "different world" of the night described in the lyrics.[14] It repeats IV–♭VII four times before breaking with the ii–V–ii–V chord progression[14] suggested by Boone.[12] The bridge further functions to emphasize the dorian quality of the next verse. The song alternates between verse and bridge again before a second break transitions to an instrumental coda, finishing the song on the major mode.[14]

Recording

The Lovin' Spoonful recorded "Summer in the City" in March 1966 at Columbia Records' 7th Avenue Studio in New York City.[16][17] Erik Jacobsen produced the song with assistance from engineer Roy Halee.[16] The band completed the song across two sessions;[18] during the first, they recorded the instrumental track in four steps, beginning with drums, an organ, electric piano and rhythm guitar.[19] John struggled to play the Wurlitzer electric piano part, leading arranger Artie Schroeck to step in as a session musician.[20][note 2] Boone overdubbed his bass while John played autoharp, with a guitar added on another layer.[22] The last instrumental overdub included added extra percussion;[19] Halee placed a microphone inside a garbage can,[23] which Yanovsky then struck the side of with a drumstick.[19] Halee described the resultant sound as "a gigantic explosion".[23]

I went in for the overdubs and mixing. [My brother] John [Sebastian] really gifted me with certain rights. He let me decide on the background vocal harmony – Joe Butler changed what he was singing per my suggestions, which really chuffed me. Just to sit there and hear my song, much changed, become this thing ... It was crazy how it sounded. It was gigantic.[16]

– Mark Sebastian, 2021

Too tired to continue recording during the initial session, John instead sang his lead vocal the next night.[19] Yanovsky and Joe Butler contributed backing vocals.[16] After hearing the initial playback, Yanovsky complained that the song's percussion was not loud enough, expressing to Halee: "I want the drums to sound like garbage cans being thrown down a steel staircase."[24] To increase the amount of reverb on the track,[23] Halee placed a microphone on the eighth floor of a metal staircase and a large speaker on the ground floor.[19][23] Halee later duplicated the effect with the same staircase when recording Simon & Garfunkel's 1969 single "The Boxer".[19][note 3] The song originally closed with a loud crash caused by a kicked Fender Reverb. Displeased with this ending, Jacobsen removed it and instead inserted a copy of the last verse and chorus for an instrumental fade out.[16]

During the sessions, the band suggested to Jacobsen that they add "city" noises to the track, such as the sound of traffic or a construction crew.[11][25] During a separate session, a radio soundman brought in an assembly of taped sound effects.[11] The group listened to the effects on a portable reel-to-reel recorder before deciding on the sound of car horns and a pneumatic drill.[19] The effects were among the first on a pop song to employ an overlapping crossfade, an effect that had typically only been used on comedy albums.[26] Mixing for "Summer in the City" concluded after the Lovin' Spoonful returned from Europe in May 1966.[27]

Release and commercial performance

Kama Sutra Records released "Summer in the City" as a single on July 4, 1966.[7][16] In the U.S. and several other countries, Boone's country song "Butchie's Tune" was used as the B-side, while in other countries, "Fishin' Blues" was used.[28] The single's release corresponded with a record heat wave in New York City[8] – peaking in June and July at 102 °F (39 °C) and 90 °F (32 °C) in August – and came shortly after a similar heat wave experienced by Britain in the end of June.[29] An advertisement promoting the single was published in the July 2 issue of Billboard magazine, promising it would "capture the feel ... of Summer in the City".[30] Author Jon Savage compares the ad's imagery, which depicts three silhouetted black boys playing with a fire hydrant, to that of a riot in Chicago's West Side which began on July 12 after police stopped young blacks from using a fire hydrant to cool off.[31]

"Summer in the City" was the Lovin' Spoonful's fifth single,[29] and one of six released between December 1965 and December 1966 that reached the top ten in the US.[32] The release rose quickly;[29] Billboard classified it as a breakout single across the U.S. on July 16,[33] and it jumped from number 21 to number seven on the Billboard Hot 100 on July 30.[29] On August 13,[29] it overtook the Troggs' "Wild Thing"[34] to become the Lovin' Spoonful's only number one.[32] It held the position for three weeks, becoming what author Jon Savage terms the "American song of the summer",[29] before losing the top spot to Donovan's "Sunshine Superman".[34] In addition to reaching number one on Cash Box[35] and Record World's Top 100 charts,[36] it was number one in Canada.[37] "Summer in the City" was later sequenced as the closing track on the album Hums of the Lovin' Spoonful,[38] released in November 1966.[39]

Kama Sutra issued "Summer in the City" in the U.K. on July 8, 1966,[40] instead backed with "Bald Headed Lena".[41] Following the success of the band's single "Daydream", which reached number two in the country in May 1966,[42] expectations were similarly high for "Summer in the City".[43] Coincident with the single's release, the band announced plans for a second tour of Britain, to be held in October,[40] but the tour was delayed after the single failed to enter the top five.[43] It peaked at number eight on the U.K.'s Record Retailer Chart.[42]

"Summer in the City" has a harder sound than the Lovin' Spoonful's previous output.[3][44] Boone later expressed pleasure that the song departed from the band's softer image,[19] helping to quickly change the attitudes of those who asked him when they were going to make "a real rock song".[16] While the band's next single, "Rain on the Roof", reached number ten on the Billboard Hot 100,[45] both Butler and Boone felt it was a mistake to release the song as the follow-up to "Summer in the City".[46] John contended the band ought to avoid releasing consecutive singles that sounded too similar.[47] However, Boone worried the return to a softer sound would alienate the band's new fans.[16][47] He later remarked: "I wonder how many people heard 'Rain on the Roof' on their radios in the early fall of 1966 and said, 'Oh, they're back to the wimpy shit,' and disregarded us all over again."[47] After 1966, the band did not achieve the same level of success;[10] Yanovsky and Boone were arrested in California in May 1966 for marijuana possession, and Yanovsky and John left the band in 1967 and 1968, respectively.[16][note 4]

Critical reception

Contemporary reviews

Among contemporary reviews, Cash Box magazine predicted a "sure-fire blockbuster", describing the song's "repeating hard-driving riff" as "contagious".[48] Record World's review panel selected the song as one of their three "single picks of the week", describing it as "[w]ild, experimental, hypnotic, terrific, positive in approach and a powerhouse release".[49] In the UK, Melody Maker's reviewer wrote that the song displayed the musical diversity of the Lovin' Spoonful, given its divergence in style from their earlier 1966 single, "Daydream", and predicted its inclusion on Hums of the Lovin' Spoonful would boost album sales in both the U.S. and the U.K.[50]

In Billboard, Johnny Borders, the program director of KLIF in Dallas, reported that while the radio station's early summer rotation had been based around oldies due to the poor quality of new music, the release of "Summer in the City" improved the situation.[51] David Dachs' 1968 book, Inside Pop, discusses the song in the context of the Lovin' Spoonful's diverse styles, while also writing its lyrics display "a hip and jazzy swing".[52]

Retrospective assessments

In a retrospective assessment, author Ian MacDonald categorizes "Summer in the City" as a "cutting-edge pop [record]"[53] and one of many "futuristic singles" to appear in 1966, such as the Beach Boys' "Good Vibrations", the Byrds' "Eight Miles High" and the Four Tops' "Reach Out I'll Be There", among others.[54] He describes it as representative of a time period when recorded songs began to employ sounds and effects difficult or impossible to recreate during a live performance; when the Lovin' Spoonful played the song in concert, John was unable to both sing and play the piano part simultaneously, requiring Butler to perform the lead vocal.[53]

Musicologist Charlie Gillett describes the song as one of the band's "evocative 'atmosphere' songs", serving as an alternative to their softer love songs through its "surprising power and intensity".[55] Richie Unterberger similarly writes that it proved the band's ability to extend beyond "sunshine and light",[56] praising its major-minor shifts and describing the sound effects as "particularly inventive" while "mercifully" not being overdone.[3] Musician Chris Stamey describes the song as a "fantastic, cinematic record" and highlights the same features as Unterberger, particularly the major-minor changes which help emphasize the two different musical moods.[57] In The New Rolling Stone Album Guide, Paul Evans also commends the sound effects and key signature changes, writing the latter retains both "a sense of wonder and deliberate naiveté".[58]

In the judgment of author Paul Simpson, "Summer in the City" is the song for which the Lovin' Spoonful are best known,[59] and author Robert Santelli describes it as the band's "most potent" song, its "forceful, aggressive" format more representative of rock than the band's traditional folk rock style.[60] Authors Keith and Kent Zimmerman call it "a twentieth-century pop classic", comparing it to Gershwin's An American in Paris and Richard Rodgers' Slaughter on Tenth Avenue.[61] Author Arnold Shaw describes the use of effects as skillful and anticipatory of those heard on the Beatles' 1967 album, Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band,[62] while author James E. Perone describes them as an example of audio vérité, concluding the song remains "one of the most iconic songs of summer of the sound-recording era in the United States."[10] In 2014, Billboard ranked the song at number 29 in a list of the top 30 summer songs,[10] and in 2011, Rolling Stone placed it at number 401 on the magazine's list of the 500 Greatest Songs of All Time.[63]

Appearance in media and other versions

"Summer in the City" served as the main theme of German filmmaker Wim Wenders' first feature film, Summer in the City (1971). In opposition to the song's theme of the hot summer, it plays over a scene where the main character walks through a cold and snowy day.[3] The song has remained relevant into the 21st century,[16] being regularly featured in television shows, movies and advertisements.[34]

"Summer in the City" has since been covered by numerous artists, including Styx, Joe Cocker and Isaac Hayes.[8][64] Blues guitarist B. B. King covered the song on his 1972 album, Guess Who, a version critic Robert Christgau describes as "clumsy",[65] and which Bill Dahl of AllMusic suggests indicates King's lack of new material.[66] The American indie band Eels recorded a cover that appeared on the deluxe edition of their 2013 album, Wonderful, Glorious, later described by Boone as "spooky and cool dirge-like".[34]

Quincy Jones recorded the song's most successful cover,[67] released on his October 1973 album You've Got It Bad Girl.[68] Valerie Simpson sings lead on the cover, supported by Eddie Louis on organ and Dave Grusin on electric piano.[68] Author Bob Leszczak describes the smooth jazz version as almost unrecognizable when compared to the original,[67] and Andy Kellman of AllMusic writes that Jones transforms the "frantic, bug-eyed energy" of the original into a "magnetically lazy drift".[68] The cover reached 102 on Billboard's Bubbling Under Hot 100 chart[67] and won Jones the Grammy Award for Best Instrumental Arrangement at the 16th Annual Grammy Awards.[69] Jones' version has been sampled by numerous hip hop artists,[16][34] including on the Pharcyde's 1992 song "Passin' Me By",[70] which incorporates the organ intro.[71]

Charts and certifications

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Personnel

According to Sam Richards of UNCUT magazine,[16] except where noted:

The Lovin' Spoonful

- John Sebastian – lead vocal, acoustic guitar, autoharp,[15] keyboards

- Steve Boone – bass, keyboards

- Joe Butler – backing vocals, drums

- Zal Yanovsky – backing vocals, lead guitar,[15] percussion[19]

Additional musician and production

- Artie Schroeck – Wurlitzer electric piano[21][note 2]

- Erik Jacobsen – producer

- Roy Halee – engineer

- Unidentified soundman – sound effects

Notes

- ↑ Some sources state Mark's song was a poem, while Steve Boone describes this as "misinformation".[7]

- 1 2 Everett instead writes the electric piano was a Hohner Pianet played by Mark.[15] In the band's recollections, Boone states the electric piano was a Wurlitzer and was played by someone he did not know.[11] John recalled struggling to play the part, at which point Schroeck stepped in to play it instead.[11][21] John further specified it was a Wurlitzer and not a Hohner Pianet.[21]

- ↑ John instead recalled in 2021 that Halee used the effect on Simon & Garfunkel's 1970 single "Bridge over Troubled Water".[16]

- ↑ During his solo career, John reached number one in 1976 with "Welcome Back", the theme song of the television show Welcome Back, Kotter.[10]

References

Citations

- ↑ MacDonald 2007, p. 202n3; Turner 2016, p. 293; Perone 2018, pp. 115, 119; Zimmerman & Zimmerman 2004, p. 119.

- ↑ Santelli 1985, p. 177.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Unterberger, Richie. "Summer in the City – The Lovin' Spoonful". AllMusic. Archived from the original on August 11, 2021. Retrieved February 16, 2022.

- ↑ Unterberger 2002, p. 212.

- ↑ Matijas-Mecca 2020, p. 112.

- ↑ Richards 2021, pp. 92–93.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Boone & Moss 2014, p. 141.

- 1 2 3 4 Besonen, Julie (August 9, 2018). "How 'Summer in the City' Became the Soundtrack for Every City Summer". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 1, 2021.

- 1 2 Applebome, Peter (August 6, 2006). "In the Summer, in the City, the Heat Changes a Tune". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 9, 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Perone 2018, p. 119.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Richards 2021, p. 93.

- 1 2 Boone & Moss 2014, p. 142.

- ↑ Boone & Moss 2014, pp. 141–142.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Everett 2009, p. 293.

- 1 2 3 4 Everett 2009, p. 87.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Richards 2021, p. 94.

- ↑ Diken 2003, p. 2.

- ↑ Diken 2003, p. 5.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Boone & Moss 2014, p. 143.

- ↑ Richards 2021, p. 94; Lenhoff & Robertson 2019, p. 127.

- 1 2 3 Lenhoff & Robertson 2019, p. 127.

- ↑ Boone & Moss 2014, p. 143: bass and autoharp overdubbed second, guitar third; Richards 2021, p. 94: Boone on bass; Everett 2009, p. 87: John on autoharp.

- 1 2 3 4 Diken 2003, p. 6.

- ↑ Richards 2021, pp. 93–94.

- ↑ Boone & Moss 2014, pp. 142–143.

- ↑ Everett 2009, pp. 357–358.

- ↑ Boone & Moss 2014, p. 122.

- ↑ Propes 1974, p. 174: b/w "Butchie's Tune" or "Fishin' Blues"; Boone & Moss 2014, pp. 107–108: Boone's country song.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Savage 2015, p. 283.

- ↑ Savage 2015, p. 286.

- ↑ Savage 2015, pp. 277, 285–286.

- 1 2 Rodriguez 2012, p. 75.

- ↑ Billboard Review Panel (July 16, 1966). "Album Reviews" (PDF). Billboard. p. 48.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Boone & Moss 2014, p. 144.

- 1 2 "Cash Box Top 100 – Week of August 20, 1966" (PDF). Cash Box. August 20, 1966. p. 4.

- 1 2 "Record World 100 Top Pops – Week of August 20, 1966" (PDF). Record World. August 20, 1966. p. 19.

- 1 2 "RPM 100 (August 22, 1966)". Library and Archives Canada. 17 July 2013. Retrieved February 16, 2022.

- ↑ Ruhlmann, William. "Hums of the Lovin' Spoonful – The Lovin' Spoonful". AllMusic. Archived from the original on August 11, 2021. Retrieved February 16, 2022.

- ↑ Zimmerman & Zimmerman 2004, p. 113.

- 1 2 Anon. (July 2, 1966). "Lovin' Spoonful sign for October tour". Melody Maker. p. 5.

- ↑ Fiske, Charles (July 16, 1966). "Fiske's Discs: You Can't Afford to Ignore This One". Evening Chronicle. p. 3 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 3 "Summer in the City". Official Charts Company. Retrieved August 30, 2020.

- 1 2 Williams 2002, p. 69.

- ↑ Savage 2015, p. 284.

- 1 2 "The Lovin' Spoonful Chart History (Hot 100)". Billboard. Archived from the original on May 21, 2022. Retrieved February 16, 2021.

- ↑ Boone & Moss 2014, pp. 148–149.

- 1 2 3 Boone & Moss 2014, p. 149.

- ↑ Cash Box Review Panel (July 16, 1966). "Cash Box Record Reviews" (PDF). Cash Box. p. 36.

- ↑ Record World Review Panel (July 9, 1966). "Single Picks of the Week" (PDF). Record World. p. 1.

- ↑ Melody Maker Review Panel (January 28, 1967). "New Records: Pop". Melody Maker. p. 13.

- ↑ Hall, Claude (July 23, 1966). "Stations Cooling Oldies for Summer" (PDF). Billboard. pp. 1, 33, 60.

- ↑ Dachs 1968, p. 41.

- 1 2 MacDonald 2007, p. 202n3.

- ↑ MacDonald 2007, p. 214n1.

- ↑ Gillett 2011, chap. 12.

- ↑ Unterberger 2002, pp. 212–213.

- ↑ Stamey 2018, pp. 13–14.

- ↑ Evans 2004, pp. 498–499.

- ↑ Simpson 2003, p. 39.

- ↑ Santelli 1985, pp. 176–177.

- ↑ Zimmerman & Zimmerman 2004, p. 119.

- ↑ Shaw 1969, p. 92.

- ↑ The Editors of Rolling Stone (April 7, 2011). "500 Greatest Songs of All Time". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on January 29, 2022.

- ↑ Leszczak 2014, p. 207.

- ↑ Christgau 1981, p. 209.

- ↑ Dahl, Bill. "B.B. King – Guess Who". AllMusic. Archived from the original on July 23, 2021. Retrieved February 27, 2022.

- 1 2 3 Leszczak 2014, pp. 206–207.

- 1 2 3 Kellman, Andy. "Quincy Jones – You've Got It Bad Girl". AllMusic. Archived from the original on December 27, 2021. Retrieved February 18, 2022.

- ↑ Jones 2001, pp. 373, 376.

- ↑ Williams 2015, p. 210.

- ↑ Barker 2017, chap. 4.

- ↑ "Go-Set Australian Charts – October 12, 1966". poparchives.com.au. Retrieved February 16, 2022.

- ↑ "The Lovin' Spoonful – Summer in the City". ultratop.be. Retrieved February 16, 2022.

- ↑ "The Lovin' Spoonful – Summer in the City". ultratop.be. Retrieved February 16, 2022.

- ↑ Nyman 2005, p. 199.

- ↑ "Toutes les Chansons N° 1 des Années 70" (in French). InfoDisc. 1966-06-18. Retrieved December 22, 2019.

- ↑ "Nederlandse Top 40 – The Lovin' Spoonful" (in Dutch). Dutch Top 40.

- ↑ "The Lovin' Spoonful – Summer in the City" (in Dutch). Single Top 100.

- ↑ "NZ Listener chart summary". Flavourofnz.co.nz. Archived from the original on May 10, 2021. Retrieved September 26, 2019.

- ↑ "Topp 20 Single 1966-35". VG-lista (in Norwegian). Retrieved 28 February 2022.

- ↑ Hallberg 1993, p. 260.

- ↑ Hallberg & Henningsson 1998, p. 225.

- ↑ "Chart Topper Top 50". Disc. August 20, 1966. p. 3.

- ↑ "Melody Maker Pop 50". Melody Maker. August 27, 1966. p. 2.

- ↑ "NME Top 30". New Musical Express. August 10, 1966. p. 5.

- ↑ "The Lovin' Spoonful – Summer in the City". Offizielle Deutsche Charts. Retrieved February 16, 2022.

- ↑ "Jaaroverzichten 1966". Ultratop. Archived from the original on 1 December 2020. Retrieved 6 April 2022.

- ↑ "Top 100-Jaaroverzicht van 1966". Dutch Top 40. Archived from the original on 24 January 2021. Retrieved 6 April 2022.

- ↑ "Top Records of 1966" (PDF). Billboard. December 24, 1966. p. 34. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 9, 2022.

- ↑ "Top 100 Chart Hits of 1966" (PDF). Cash Box. December 24, 1966. pp. 29–30. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 17, 2022.

- ↑ "British single certifications – Lovin' Spoonful – Summer in the City". British Phonographic Industry. Retrieved June 18, 2021.

- ↑ "American single certifications – Lovin' Spoonful – Summer in the City". Recording Industry Association of America. Retrieved June 18, 2021.

Bibliography

- Barker, Andrew (2017). The Pharcyde's Bizarre Ride II the Pharcyde. 33⅓ series. New York City: Bloomsbury Publishing USA. ISBN 978-1-5013-2129-0.

- Boone, Steve; Moss, Tony (2014). Hotter Than a Match Head: My Life on the Run with The Lovin' Spoonful. Toronto: ECW Press. ISBN 978-1-77041-193-7.

- Christgau, Robert (1981). Christgau's Record Guide: Rock Albums of the Seventies. New Haven, Connecticut: Ticknor & Fields. ISBN 0-89919-026-X.

- Dachs, David (1968). Inside Pop: America's Top Ten Groups. New York City: Scholastic Book Services. OCLC 2198803.

- Diken, Dennis (2003). Hums of the Lovin' Spoonful (Liner notes). The Lovin' Spoonful. Kama Sutra Records. 74465 99732 2.

- Evans, Paul (2004). "The Lovin' Spoonful". In Brackett, Nathan; Hoard, Christian (eds.). The New Rolling Stone Album Guide. New York City: Simon & Schuster. pp. 498–499. ISBN 978-0-7432-0169-8.

- Everett, Walter (2009). The Foundations of Rock: From "Blue Suede Shoes" to "Suite: Judy Blue Eyes". Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-531024-5.

- Gillett, Charlie (2011). The Sound of the City: The Rise of Rock and Roll. London: Souvenir Press. ISBN 978-0-285-64024-5.

- Hallberg, Eric (1993). Eric Hallberg presenterar Kvällstoppen i P3: Sveriges Radios topplista över veckans 20 mest sålda skivor. Drift Musik. ISBN 9163021404.

- Hallberg, Eric; Henningsson, Ulf (1998). Eric Hallberg, Ulf Henningsson presenterar Tio i topp med de utslagna på försök: 1961–74. Premium Publishing. ISBN 919727125X.

- Jones, Quincy (2001). Q: The Autobiography of Quincy Jones. New York City: Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-48896-9.

- Lenhoff, Alan S.; Robertson, David E. (2019). Classic Keys: Keyboard Sounds That Launched Rock Music. Denton, Texas: University of North Texas Press. ISBN 978-1-57441-786-9.

- Leszczak, Bob (2014). Who Did It First?: Great Rock and Roll Cover Songs and Their Original Artists. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-4422-3322-5.

- MacDonald, Ian (2007). Revolution in the Head: The Beatles' Records and the Sixties (Third ed.). Chicago Review Press. ISBN 978-1-55652-733-3.

- Matijas-Mecca, Christian (2020). Listen to Psychedelic Rock! Exploring a Musical Genre. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-4408-6198-7.

- Nyman, Jake (2005). Suomi soi 4: Suuri suomalainen listakirja (in Finnish) (1st ed.). Helsinki: Tammi. ISBN 951-31-2503-3.

- Perone, James E. (2018). Listen to Pop! Exploring a Musical Genre. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-4408-6377-6.

- Propes, Steve (1974). Golden Oldies: A Guide to 60's Record Collecting. Radnor, Pennsylvania: Chilton Book Company. ISBN 978-0-8019-6062-8.

- Richards, Sam (September 2021). Bonner, Michael (ed.). "The Making of ... Summer in the City by The Lovin' Spoonful". UNCUT. No. 292. pp. 92–94.

- Rodriguez, Robert (2012). Revolver: How the Beatles Re-Imagined Rock 'n' Roll. Montclair, New Jersey: Backbeat Books. ISBN 978-1-61713-009-0.

- Santelli, Robert (1985). Sixties Rock: A Listener's Guide. Chicago: Contemporary Books. ISBN 978-0-8092-5439-2.

- Savage, Jon (2015). 1966: The Year the Decade Exploded. London: Faber & Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-27762-9.

- Shaw, Arnold (1969). Rock Revolution: What's Happening to Today's Music. London: Crowell-Collier Publishing Company. ISBN 0-02-782400-4.

- Simpson, Paul (2003). The Rough Guide to Cult Pop. London: Rough Guides. ISBN 978-1-84353-229-3.

- Stamey, Chris (2018). A Spy in the House of Loud: New York Songs and Stories. Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-1-4773-1624-5.

- Turner, Steve (2016). Beatles '66: The Revolutionary Year. New York City: Ecco. ISBN 978-0-06-247558-9.

- Unterberger, Richie (2002). Turn! Turn! Turn!: The '60s Folk-Rock Revolution. San Francisco, California: Backbeat Books. ISBN 0-87930-703-X.

- Williams, Paul, ed. (2002). The Crawdaddy! Book: Writings (and Images) from the Magazine of Rock. Milwaukee, Wisconsin: Hal Leonard Corporation. ISBN 0-634-02958-4 – via Google Books.

- Williams, Justin A. (2015). "Intertextuality, sampling, and copyright". In Williams, Justin A. (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Hip-Hop. Cambridge University Press. pp. 206–220. ISBN 978-1-107-03746-5.

- Zimmerman, Keith; Zimmerman, Kent (2004). Sing My Way Home: Voices of the New American Roots Rock. San Francisco, California: Backbeat Books. ISBN 978-0-87930-790-5.

External links

- "'Summer in the City' b/w 'Butchie's Tune'" at Discogs (list of releases)

- "'Summer in the City' b/w 'Fishin' Blues'" at Discogs (list of releases)