Stalinist repressions in Azerbaijan were repressions carried out in the Azerbaijan SSR from the late 1920s to the early 1950s that affected not only the top leaders of Azerbaijan, but also the clergy, intellectuals, wealthy peasants, and the entire population of Azerbaijan. Repressions included shooting, arresting, sending to labor camps, and deporting the population to other regions of the USSR. People suspected of counter-revolutionary activity, espionage, anti-Soviet propaganda, or obstructing the nationalization of their property were persecuted.

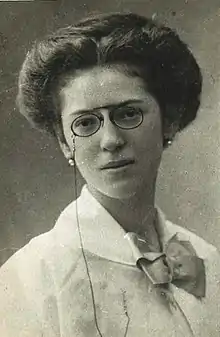

Repression reached its peak during the Great Purge, which was carried out by the NKVD under the direction of higher authorities. This period coincided with the leadership of Mir Jafar Baghirov, who ruled Azerbaijan for 20 years. In Soviet literature, his name is often mentioned in connection with the mass repressions that occurred in the 1930s, as he was typically the main initiator of the repressions that took place in the republic in 1937–1938. However, literature written during and after Perestroika has not yet clearly reflected the extent of Baghirov's responsibility for these events.[1] Swedish political scientist Svante Cornell referred to him as the "Azerbaijan's Stalin",[2] while Russian philosopher and historian Dmitry Furmanov called him the "Azerbaijani Beria".[3]

Events before repressions

The origins of repression can be traced back to the period when Stalin rose to power and began ruling the country alone. The complex party environment and the political, social, and economic difficulties that occurred in the first half of the 20th century led to people being accused of Trotskyism, nationalism, maliciousness, espionage, and other charges. The official ideological basis for Stalin's repressions was the concept of "strengthening the inter-class struggle in connection with the end of the construction of socialism," which was formulated by Stalin at the plenum of the Central Committee of the CPSU held in July 1928.

However, there are differing perspectives regarding the causes of the Great Purge. For instance, party veteran Nemtsova, a survivor of Stalin's camps, expressed her views in a 1988 interview with Ogoniok magazine. She was convinced that the repressions of 1937-1938 were orchestrated by White Guards and gendarmes who had infiltrated the NKVD in Moscow and Leningrad.[4]

Stalin's rise to power

From its creation, the Bolshevik wing of the Russian Social-Democrats was embroiled in an almost continuous internal struggle. However, the reason for the Bolsheviks' fierce struggle during the revolution and their superiority in the civil war was their internal solidarity and unification in a rigidly centralized organization around a charismatic leader like Lenin. In contrast to the Esers, who had split into factions by the end of 1917, and the Mensheviks, who were divided into factions that almost rivaled each other until the revolution, the Bolsheviks were able to maintain their unity despite several disagreements.

At the end of the civil war, the political landscape changed dramatically. The party became the only legal political organization in the territories of the RSFSR, TSFSR, Ukrainian SSR, and Belorussian SSR, which united in 1922 to form the Soviet Union. Members of former parties began to join the party's ranks, with a quarter of the representatives at the 20th Congress coming from other parties, mainly Mensheviks. After Lenin's death, the Lenin Call led to a massive increase in party membership, including those who did not share Bolshevik ideas but joined for career advancement.

.jpg.webp)

Lenin's illness intensified the struggle between factions within the Communist Party. At the top echelons, there was a ruthless struggle for succession. Within the Politburo, Joseph Stalin, Grigory Zinoviev, and Lev Kamenev formed a "troika" against Leon Trotsky. After Trotsky's defeat, Stalin turned against his former allies in the troika. In 1926, Trotsky, who rejected Stalin's theory of socialism's victory in one country, joined forces with Grigory Zinoviev and Lev Kamenev to form a united opposition. In 1927, several events occurred that led to the beginning of Stalin's repressions. In May, England broke off diplomatic relations with the Soviet Union, and on June 7, Soviet ambassador Pyotr Voykov was assassinated by a monarchist in Warsaw. As there were still a small number of monarchists and white guards in the opposition camp, they were the first to face repression. The killing of Voykov led to the complete destruction of monarchist and white guard cells throughout the USSR. England's "threat of war" prompted further action against intra-party rivals and dissidents. That summer, the NKVD arrested monarchists, white guards, landowners, merchants, priests, and churchmen in the main grain-growing regions. This allowed Stalin to break Bukharin's group's resistance and pass a decision to remove Lev Trotsky and Grigory Zinoviev from the Central Committee as "spies of the united opposition".[5]

As a result of the internal party struggle, Stalin managed to suppress his opponents. Lev Trotsky, a prominent figure of the revolution and the author of Trotskyism (a trend of Marxism), was expelled from the country in 1929. Grigory Zinoviev was also exiled, but after expressing regret for his actions, he was allowed to return to the party. However, in 1932, he was arrested and exiled to Kazakhstan. Various historians believe that Stalin came to power alone between 1926 and 1929. In 1929, Stalin declared it "the year of the great turn" with collectivization, industrialization, and cultural revolution as the state's strategic goals.

Situation in Azerbaijan

Before the revolution, two Muslim social-democratic parties were formed in Azerbaijan: Hummet, which would later split into Bolshevik and Menshevik wings, and the Adalat party, founded by southern Azerbaijani immigrants. Competing with them were the liberal Musavat and the Islamist Ittihad party. The differences between members of the Musavat and Hummet parties were more related to their origins and social status than their worldviews. Almost all members of Hummet were peasants, impoverished gentlemen, oil workers, or Iranian immigrants. They were united by the education they received in Russian-Tatar schools and religious schools, and the party's membership grew through acquaintances, relatives, and relationships of dependence.[6] During the civil war, members of Hummet's Bolshevik wing passed through Astrakhan, while the Menshevik wing operated illegally in Baku. Members of this wing were also represented in the Musavat-dominated Azerbaijan parliament.

In 1920, Hummet, Adalat, and the Baku committee of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) united under the name of the Azerbaijan Communist Party. According to Olga Shatunovskaya's testimony, there was a struggle between two groups: nationalist communists led by Nariman Narimanov and internationalists fighting against previous traditions.[7] The leaders of Musavat's right wing emigrated to foreign countries, while members of its left wing were allowed to exist.[8] Despite the disintegration of the Musavat party and some members taking an oath of loyalty to the new government, Musavatism's ideas did not disappear. Some Musavat members held important positions in Baku city councils and educational institutions.[9] Even though Ittihad announced its dissolution, it remained influential for a long time.

Initially, the Revolutionary Committee of the Azerbaijan SSR and the Council of People's Commissars of Azerbaijan SSR were dominated by Muslims, who were referred to as nationally oriented communists. Despite Muslims having a majority in the Central Committee and the Presidium, Russian and Armenian communists had significant influence in the Central Committee in the early 1920s. According to German historian Baberowski, Moscow's influence arose through Grigory Kaminsky and Alexander Yegorov, and later through Sergei Kirov, who headed the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Azerbaijan for 7 years (1921–1926).[10] However, Russian historian A. Kirillina does not accept Sergey Kirov as Moscow's "vicegerent" because Nariman Narimanov was the main leader in the republic at that time. The Baku Presidium could not implement its decisions without the consent of the Transcaucasian State Committee and the Caucasus Bureau, which played a coordinating role between the Moscow Central Committee and the Azerbaijan party organization. The Baku city committee of the party was dominated by Russians and Armenians, while Muslim communists were mainly represented in district party committees and state offices.[10] From the first half of the 1920s, Stalin began to worry about the mood among the main figures (elites) of national parties. In his letter to Lenin in 1922, he noted:

During the four years of civil war, we were forced to show Moscow's liberality in national affairs due to our intervention in the republics. Without our own will, we succeeded in cultivating real, systematic social-libertarians who demanded comprehensive freedom and regarded the interventions of the Central Committee of the Russian Communist Party as lies and hypocrisy by Moscow.[11]

Localization of the apparatuses began during Nariman Narimanov's period, who did it without the support of the Moscow party apparatus. However, to prevent future threats from nationally oriented communists, Moscow started nationalization and indigenization in the second half of 1923.[12] Along with Mirsaid Sultan-Galiev, Turar Ryskulov, Filipp Makharadze, Budu Mdivani, Nariman Narimanov was also one of the prominent representatives of nationally oriented communists. However, in 1923 he fell into disrepute and his supporters were persecuted. According to Yusif Gasimov's memoirs, in the second half of the 1920s, a struggle for leadership in Azerbaijan began between two groups. On one side were Ruhulla Akhundov, Habib Jabiyev, Huseyn Rahmanov, Muzaffar Narimanov, and G. Farajzade. On the other side were Gazanfar Musabekov, Sultan Majid Afandiyev, M. Garayev and Yusif Gasimov.[13]

After the assassination of Sergei Kirov, from 1926 to 1929, the first secretary of the Communist Party of Azerbaijan was entrusted to a secretariat consisting of Aliheydar Garayev, Huseynbala Agaverdiyev (from 1927 his position was held by Yusif Gasimov), and Levon Mirzoyan.[14] After being informed about the arbitrariness and nepotism of the party leadership in Azerbaijan, Stalin began to purge the party leadership in 1929. Aliheydar Garayev, Levon Mirzoyan, Yusif Gasimov, and others were fired from their posts. From September 1929 to February 1930, there was no leadership in Azerbaijan. After eliminating the leading officials in Baku, Stalin supported Levon Mirzoyan and Aliheydar Garayev and started changing the secretaries of the district committees. As a result of the mixing of Azerbaijani party leaders, a mixed network of personal connections was destroyed. Internal party intrigues and quarrels continued during the period of Nikolai Gikalo and Vladimir Polonsky, the leaders of Azerbaijan's next party organizations. As a result, in 1933, Stalin appointed Mir Jafar Baghirov to lead Azerbaijan instead of Polonsky.[15]

Political repressions between 1930–1936

On December 1, 1934, Sergei Kirov, the head of the Leningrad Regional Committee of the CPSU, was shot and killed by Leonid Nikolayev, an unemployed man, in the Smolny Palace in Leningrad. Stalin used this murder as a pretext to eliminate the opposition leaders of the 1920s and 1930s. He accused Grigory Zinoviev and Lev Kamenev of being behind the assassination and ordered the investigation of the "Zinoviev trail" despite the objections from the NKVD.[16]

In the first few months following Kirov's murder, the repressive campaign in Azerbaijan had not yet reached serious proportions.[17] However, some measures had been taken. At the proposal of the Central Committee of the Azerbaijan SSR, the Politburo decided to deport 87 golchomags, who were considered incorrigible anti-Soviet elements and former heads of large capitalist enterprises. The families of golchomags who had fled to other regions of the union were also deported, along with the confiscation of their property from the territory of the Azerbaijan SSR, to prison camps.[17]

In the spring of 1936, a group of former Trotskyists working in the field of humanitarian sciences were arrested in Baku.[18] Subsequently, the "nationalists" were also arrested. Among them was Ahmad Trinich, a publicist of Albanian origin who had hostile relations with Mir Jafar Baghirov. He was the first to be arrested.[19] In April of that year, during a meeting of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Azerbaijan SSR, Baghirov presented a letter, either found or fabricated, that contained Trinich's request for protection from the Musavat parliament in 1918. As a result, Trinich was expelled from the party and arrested. During the investigation, he committed suicide by swallowing a button.[19] However, the first major wave of arrests in Azerbaijan occurred in the autumn and primarily targeted dissidents within the Bolshevik party, members of neo-Bolshevik parties, and those suspected of disloyalty to Stalin's rule.[20]

In November, the NKVD arrested dozens of prominent communists, accusing them of Trotskyism, dissension, and espionage.[21] Among those arrested was Bagirov's personal secretary, Nikishov, who was accused of being a "Musavat agent" and "terrorist". Several other notable individuals were also expelled from the party and arrested, including Balabey Hasanbayov, the rector of Azerbaijan State University; Ibrahim Eminbeyli, the director of Azernashr; well-known ethnologists and professors Alexander Bukshpan and Nikolayev; Orbelyan, a member of the Supreme Court; and Veli Khuluflu, the chairman of the League of Militant Atheists.[22] At the end of the year, Baghirov wrote to Stalin, stating that:

Some officials in Azerbaijan have raised doubts among us. These include Ruhulla Akhundov, the chairman of the art affairs committee; Museyib Shahbazov, the commissioner of public education of Azerbaijan; and Ayyub Khanbudagov, the deputy chairman of Azerittifaq. Based on a statement by the counter-revolutionary Trotskyist Mikhail Okudjava regarding Ruhulla Akhundov, we have instructed the NKVD to conduct an investigation. During a personal meeting with comrade Sarkisov, it was determined that Eyyub Khanbudagov is indeed an active Trotskyite. Comrade Sarkisov also provided a reference letter to this effect.[23]

During this period, rebel groups emerged among villagers, such as those in the Ali-Bayramli district.[20] The entire male population of Ali Bayramli was accused of preparing for a counter-revolutionary coup and subsequently subjected to repression.[24]

In December, district leaders were subjected to repression. The entire party leadership in Nakhchivan was arrested by NKVD, and Mehdi Mehdiyev, the first secretary of the party regional committee of Nakhchivan, was charged with "relations with the enemy and criminal elements" and subsequently executed.[22] The secretaries of Ali Bayramli, Goychay, Gazakh, Gasim Ismayilov, Gonaqkend, Lankaran, Norashen, Samukh, Surakhani, and Shamkhor regions also faced repression.[22]

In early 1937, a group of party leaders and Soviet workers were prosecuted for political crimes. Among those arrested was Ruhulla Akhundov, the former secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Azerbaijan and the Transcaucasian State Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union.[20]

Great Purge in Azerbaijan

Initiation of mass purges

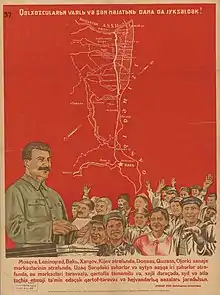

At the Congress of the Central Committee of the CPSU, held in Moscow from February 23 to March 3, 1937, Stalin reiterated his doctrine of "sharpening the class struggle on the road to building socialism." He also delivered a speech titled "On the deficiencies in the work of the Party and the elimination of Trotskyists and hypocrites." Following this, mass repressions began. Mir Jafar Baghirov also participated in this plenum.

Upon returning to Baku on March 19, Baghirov convened the VI Congress of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Azerbaijan and informed the representatives about the Moscow Congress. In his speech, Baghirov highlighted the issues of ignorance and illiteracy in the country and attributed them to the activities of counter-revolutionaries and Trotskyists. He concluded his speech with a threat to destroy the entire party leadership.[25] At the congress, individuals such as Asgar Farajzade, the chairman of the State Planning Committee, Mammad Juvarlinski, Mukhtar Hajiyev, M. Mammadov, A. Peterson, Mehdi Mehdiyev, H. Huseynov, L. Rasulov, Gurevich, B. Pirverdiyev, and candidates for membership of the Central Committee M. Naibov, K. Bagirbeyov, and L. Mesheryakov were removed.[26] Of all the members expelled from the Central Committee, only M. Naibov was also expelled from the party.[27]

On March 21, during a meeting of the ACP Baku committee, Baghirov spoke about the responsibilities of leaders towards their subordinates. In his speech, he said:

A leader is responsible for their employees. If a leader surrounds themselves with unproductive, corrupt, or villainous individuals and fails to recognize this, then they are not a true leader or Bolshevik, but rather a 'hat' or perhaps even an enemy. Have the managers of our oil industry discovered much damage?[28]

While addressing the hall, Baghirov mentioned the People's Commissar of Agriculture, Heydar Vazirov, and said, "Do you think that Vazirov will change his ways from tomorrow and remove the corrupt individuals around him? Not at all". Later, Bagirov addressed the People's Commisar of Public Education, Museyib Shahbazov, and the Chairman of the Azerbaijan SSR Council of Ministers, Sultan Majid Efendiyev, before finally saying the following:

To those who ask where shamelessness can be found, let me say that it can be found in districts, offices, schools, workshops, drilling offices, collective farms, tractor units, machine tractor stations, higher education institutions, theaters, cinemas, police departments, opposition offices, and even first party meetings. It can be found everywhere, in places where the enemy has penetrated or is trying to penetrate. Indeed, shortcomings and mistakes have been discovered there and it is necessary to fight to the death with our cruel enemies for the sake of our party and our socialist homeland. This is what we are talking about. Because we are a border republic and because of the multi-ethnicity of Azerbaijan, we must examine every suspicious person as an enemy of the party, a traitor, a spy.[29]

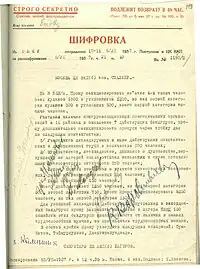

On July 2, 1937, the Politburo of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine adopted Decision No. P51/94 "on anti-Soviet elements". The instructions, written by Stalin himself, prove that the events that took place were his own initiative:[30]

_%E2%84%96_%D0%9F5194.jpg.webp)

To the Central Committee secretaries of provincial and district committees and communist parties of the republics:

It has been observed that former golchomags and criminals, who were exiled to the northern and Siberian regions of the country, returned to their regions after their liberation and became the main instigators of anti-Soviet and subversive crimes in the regions' collective farms, state farms, transport, and other areas of industry.

The Central Committee of the CPSU (b) suggests that the secretaries of all provincial and district committees, as well as the representatives of the NKVD of all provincial and district committees and republics, should immediately arrest the criminals who return to their native regions and those who show the most hostile attitude. Their cases should be submitted to the triads in an administrative manner, and they should be shot. Those who are in a hostile position but show less activity should be re-marked and exiled to other regions under the instructions of the NKVD.

The CPSU (b) proposes that within five days, members of the troika, as well as the number of persons to be shot and deported, should be presented to the Central Committee.

On July 3, the Politburo of the Central Committee of the CPSU (b) sent telegrams to the secretaries of the Central committee of all provincial and district committees and republican communist parties. On July 9, Mir Jafar Baghirov sent an encrypted telegram to Moscow asking about the number of people who should be subjected to repression and what measures should be taken against them. In the telegram, it was requested to deport the family members of persons who were members of certain criminal groups and to entrust the cases of other groups of the population to the NKVD troika. Baghirov suggested approving Yuvelian Sumbatov, Teymur Guliyev, and Jahangir Akhundzade as members of the troika team in Azerbaijan.[31] The next day, the Politburo of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine (b) issued a resolution regarding the determination of the troika's staff and the number limit of persons who would be subject to repression. The part of the resolution related to Azerbaijan was:

The troika members of Azerbaijan SSR, Yuvelian Sumbatov, Teymur Guliyev, and Jahangir Akhundzade, was approved. The planned shooting of 500 criminals and golchomags and the deportation of 1,300 golchomags and 1,700 criminals were approved. Cases of counter-revolutionary organizations were allowed to be tried by the troika, imposing the deportation of 750 people, the deportation of 150 families of members of criminal groups to NKVD camps, and the execution of 500 people.[20]

On July 14, the Politburo of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine made a decision about the "border line of the Eastern republics." The decision provided for the establishment of border lines in some republics to strengthen the protection of the state border with Iran and Afghanistan. All regions of Nakhchivan ASSR in Azerbaijan, and Astara, Astrakhan Bazar, Bilasuvar, Jabrayil, Zangilan, Zuvand, Garadonlu, Garyagin, Lankaran and Masalli districts were included in this line. The NKVD was entrusted with the expulsion of "unreliable elements" from all these regions. A special regime of residence and movement was established in the border zones, and foreign citizens could only settle here with the permission of the USSR government. The People's Commissariat of Foreign Affairs of the USSR was instructed to inform about the cancellation of the convention signed between Iran and the USSR on "simplified border crossing for residents of border regions."[32]

The decision of the Politburo of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine on July 2 was implemented according to the order of the Central Committee of the Republic of Uzbekistan No.00447 issued on July 30 about the "operation of repression of criminals and other anti-Soviet elements of former golchomags". This order was confirmed by the Politburo of the Central Committee of the CPSU the next day. Those who would be subject to repression under the order included:

- Former golchomags who served their sentences and returned or escaped from prisons, labor camps, as well as golchomags who hid from the policy of abolishing golchomags as a class and engaged in anti-Soviet activities.

- Former golchomags and socially dangerous elements who are members of rebel, fascist, terrorist, criminal groups.

- Members of anti-Soviet parties (Esers, Georgian Mensheviks, Mussavatists, Ittihadists and Dashnaks), remigrants, those hiding from repressions, those who escaped from the place of their arrest and engaged in active anti-Soviet activities.

- Members of Cossack and White Guard organizations.

- Anti-Soviet elements, convicts, criminals, white guards, active sectarians, churchmen, and others, including less active former golchomahs kept in prisons, camps, labor camps, and colonies.

- Felons and criminals who are in prison, but whose personal cases have not yet been tried by the court.

- Criminals held in detention and labor camps and engaged in criminal activities there.

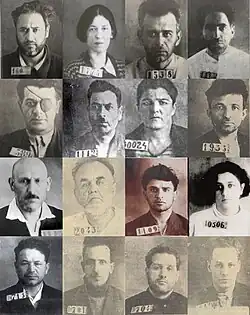

In the autumn of 1938, repressions in Azerbaijan reached their peak with the creation of the troika. People of all nationalities were subjected to these repressions.[20] In 1937, 57 factory and production enterprise directors, 95 engineers, 207 Soviet and trade union workers, and 8 professors were arrested. That same year, the troika sentenced 2,792 people to be shot and 4,425 to long-term imprisonment for political crimes.[20] Azerbaijanis, as well as Russians, Armenians, Jews, and other nationalities, were among those subjected to repression.[24] As a result, hundreds of employees of the Azerbaijan Caspian Shipping Company, mainly consisting of Russians, Jewish Armenians, and a few Azerbaijanis, were accused of counter-revolutionary activities and brought to trial.[33]

In 1955, Adil Babayev, the prosecutor of the Azerbaijan SSR, described that period in a report presented to Imam Mustafayev, the first secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Azerbaijan:

According to NKVD information, all sections of Azerbaijan's population were involved in counter-revolutionary activities and joined various counter-revolutionary organizations. Old underground party workers were declared enemies of the Soviet Union, party leaders and Soviet workers easily attracted each other to different counter-revolutionary organizations, Armenians became mussavatists, Russian workers fought for the establishment of bourgeois-nationalist power in Azerbaijan, and old professors were labeled as fighters of terrorist groups. The lack of political and cultural knowledge among some NKVD employees led to ridiculous accusations against those arrested, such as causing damage due to the production of low-quality mukhamor paper, breaking a cart wheel due to damage, separating Azerbaijan from the TSFSR and becoming an allied republic, and finally separating Azerbaijan State University from the state.[33]

Terror activity

Military purges

Since 1936, members of the Workers and Peasants Red Army have been arrested. On June 11, 1937, Marshal Mikhail Tukhachevsky and seven others (Iona Yakir, Ieronim Uborevich, Roberts Eidemanis, Boris Feldman, August Kork, Vitaly Primakov, Vitovt Putna) were brought before a secret trial with the participation of the Supreme Court of the USSR. All the accused were allegedly members of an anti-Soviet Trotskyist military organization and were in contact with Lev Trotsky, his son Lev Sedov, Georgy Pyatakov, Leonid Serebryakov (who had been convicted in January 1937), Nikolai Bukharin and Alexei Rykov (who had been imprisoned by that time), and the German General Staff. The goal of the organization was to seize power in the event of the USSR's defeat against Germany and Poland.

The accusation of participation in "military-fascist collaboration" launched against the leadership of the Red Army did not spare the allied republics. On July 16, 1937, Mir Jafar Baghirov reported the exposure of a counter-revolutionary organization that included Gambay Vazirov, commander of the 77th Azerbaijani mountain-shooting division, and D. A. Aliyev, head of the division's political department. They were also members of a nationalist organization.[34] Division commander Gambay Vazirov was arrested by the NKVD on July 29, accused of attempting a military coup, and subsequently executed.[35][36] Azerbaijani division brigade commander Jamshid Nakhchivanski, Hasan Rahmanov, and brigade commissar Jabbar Aliyev were also subjected to repression.[37][38] On August 7, Colonel A. Abbasov, who was temporarily appointed as the division commander, and A.Dadashov, the military commissar of the division, reported to Nikolay Kuibyshev, the commander of the Transcaucasian Military District, about the dismissal of several commanders.[35] In the following days, A. Dadashov reported the dismissal of several individuals. However, in his August 11 telegram, he reported the arrest of A. Abbasov:

Abbasov, who was temporarily acting as division commander, has been arrested. Per your order, I have appointed Zyuvanov to temporarily act as commander and Tumanya to act as divisional chief of staff.[35]

Colonel A. Abbasov was accused of counter-revolutionary activity. In April 1938, a special session of the NKVD sentenced him to 8 years in a correctional labor camp. However, in September 1941, Military Collegium of the Supreme Court convicted him under Articles 58-2, 58-8, 58-10, and 58-11 of the RSFSR Penal Code and issued a death sentence based on these articles.[35] Telegrams regarding arrests in the 77th Division continued to arrive until autumn of 1937.[39] That year, 110 military personnel were arrested in Azerbaijan.[20][40]

The presence of repressions in the Red Army frightened commanders and political workers, leading to new denunciations and arrests. Repressed commanders were replaced by young personnel who lacked the specialization and experience to command large military formations. The extraordinary transfer of command management staff resulted in constant changes and increases in duties, negatively affecting the military field. Those in office often avoided responsibility, viewing their positions as temporary. As a result, the combat readiness of the Red Army, including the Caucasian national divisions, weakened during 1937–1938. In November 1937, the military training of the Transcaucasian military district was deemed unsatisfactory by the Military Council. Kuibyshev, commander of the Transcaucasia Military District, attributed this to repressions. The Azerbaijan division was commanded by a major with no experience.[41]

On March 7, 1938, the Council of People's Commissars decided to re-form and directly subordinate the national military units, formations, and military schools of the Workers and Peasants Red Army to the center. According to Rizvan Zeynalov, ruling the country with the system of administrative emirates during the Stalin's rule was a wrong decision. As a result, the armed forces were weakened during the German attack on the USSR.[42]

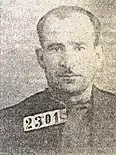

Repressions against republic leaders and party members

According to German historian Jörg Baberowski, Azerbaijan was virtually ungovernable from the beginning of the summer of 1937 to the autumn of 1938.[29] In 1937, 22 people's commissars, 49 regional committee secretaries, and 29 regional executive committee chairmen were arrested.[20] 18 people's commissars and all district committee secretaries died.[43] Along with the people's commissars of agriculture, education, and justice, their deputies and almost all their employees were repressed.[43]

The arrest of several party and state officials was due to petitions (denunciations) written against them. Ivan Menyaylov, the head of the Caspian Shipping Company who received the death sentence, mentioned the names of 138 people he was involved in harmful activity with. Among them were Huseyn Rahmanov, brother of Hasan Rahmanov, who was the former head of the political department of the Caspian Sea Shipping Company, the first secretary of the Nakhchivan Provincial Committee, and chairman of the Council of People's Commissars of the Azerbaijan SSR.[44] According to Eldar Ismayilov, Baghirov appealed to Stalin regarding the dismissal of Hasan Rahmanov and the inadmissibility of his brother remaining in the country's leadership.[45] On September 26, 1937, Stalin sent a coded telegram to the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Azerbaijan:

To the Baghirov, Baku, Azerbaijan CP Central Committe The CPSU Central Committe confirms the arrest of Huseyn Rahmanov and Hasan Rahmanov. We ask you to carefully clean the Nakhchivan defiled by Hasan Rahmanov. Please note that the Nakhchivan is the most dangerous point in the entire Transcaucasia. It is necessary to appoint a verified real Bolshevik administration there. Yusif Gasimov will be directed to you.[46]

The leadership of Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast (NKAO) was also subjected to repression.[33] Kotanjian, the arrested secretary of Mardakert district party committee, mentioned Pogosov, the first secretary of the NKAO, as one of those who attracted him to the nationalist Armenian organization. In October 1937, at the plenum of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Azerbaijan SSR, Pogosov was dismissed from the Central Committee ranks and tried together with other Armenian party members.[47]

Four out of five people's judges in Azerbaijan were arrested, leaving almost the entire prosecutor's office without personnel.[43] In the spring of 1937, almost all judges and prosecutors of the Kirovabad district were arrested after Mustafayev, the first secretary of the Kirovabad party organization, stated that the judicial and prosecutorial authorities were not decisive enough in fighting against criminal elements in kolkhozs.[48] According to Baberowski, Baghirov's witch hunt brought the party-economic apparatus in Azerbaijan to the verge of self-destruction and into a terrible vortex.[49]

Repressions created ideal conditions for Baghirov to kill his political opponents, and he took advantage of these conditions. According to information available in May and June 1937, some Azerbaijani communists, including the commissar of public education Mammad Juvarlinski and Hamid Sultanov, tried to complain to Moscow about Mir Jafar Baghirov. These attempts ended tragically for them.[50] Mammad Juvarlinski worked as the first secretary of the Nukha (Sheki) Committee of Azerbaijan Communist Party (AZCP) and Commissar for education of the Azerbaijan SSR. He was also a member of the central committee of AZCP. In 1937, Baghirov, speaking from the party group at the Congress of Soviets of the Azerbaijan SSR, called Juvarlinski a nationalist, who amended the Constitution of the Azerbaijan SSR. On March 17, Politburo, and on the 19th, the plenum, at the suggestion of Mir Jafar Baghirov, dismissed Juvarlinski from the office of the Central Committee, and on the 29th, they removed him from the party ranks. Juvarlinski went to Moscow to complain, but Baghirov got ahead of him and arrested him. He was shot on October 13, 1937.[51]

Chingiz Ildyrym was also subjected to repression. Previously, he played a key role in the April invasion as the head of the Azerbaijani Navy. During the Great Purge, Chingiz Yıldırım, who was serving as a factory director in Krivoy Rog, was arrested under the pretext of being a "son of bey". He was brought to Baku, tortured, and then sent to Moscow where he was executed.[52][53] After him, Ayyub Khanbudagov, the former chairman of the Cheka of Azerbaijan, was arrested for his nationalist speeches in 1924.[52] On July 23, 1937, at a special meeting of the NKVD, Khanbudagov was sentenced to 5 years in prison. However, on October 12, 1937, the mobile session of the Military Collegium changed his sentence to death.[54] According to the decision of the Supreme Court of the USSR on December 26, 1957, Khanbudagov was acquitted. Hamid Sultanov testified against him.[55] In November 1937, the troika sentenced Sumbat Fatalizade to 8 years in a labor camp, where he died.[56][57]

In 1938, Mikhail Rayev-Kaminsky, who was the People's Commissar of Internal Affairs of the Azerbaijan SSR and a member of the Azerbaijan NKVD troika, was arrested while he was in Baghirov's room.[58] According to the testimony of investigator Pavel Khentov, he admitted to participating in the beating of the arrested individuals.[20] He was executed in 1939 and was never acquitted.[59] To avoid arrest, some communists either feigned insanity or committed suicide. For example, Gulbis, who was the head of Azneft, threw himself under a train in the summer of 1937 after learning that he would soon be arrested at the Baku railway station.[43]

The repressions left the Communist Party of Azerbaijan without a middle class and decimated most of its party leadership.[60] All members of Hummet, except for Mir Bashir Gasimov and Yusif Gasimov, were victims of repression, and those whose names were mentioned were arrested.[43] The "old guard" of the communist elite was decimated.[61] Dadash Bunyadzade,[62] Sultan Majid Afandiyev,[63] Hamid Sultanov and his wife Ayna Sultanova,[64] Teymur Aliyev[65] Ruhulla Akhundov,[43] Huseyn Rahmanov, Chingiz Ildyrym, Mirza Davud Huseynov,[66] Mustafa Quliyev,[67] Aliheydar Garayev, Gazanfar Musabekov[68] and Isay Dovletov were also subjected to repression.[69]

Although the membership of the Communist Party of the Azerbaijan SSR (ACP) fluctuated throughout its history, the number of party members decreased during the Great Purge. This decrease was not only due to executions and arrests, but also due to expulsions from the party ranks and other reasons. On January 1, 1937, before the Great Purge, the total number of members and candidates of the Azerbaijan Communist Party was 47,194. However, by January 1, 1938, this number had decreased to 45,331. After the conference of the party's Baku Committee held in May 1937, 36 members and 4 candidates of the Baku City Committee were arrested by the NKVD in 1938. Decreases were also observed between congresses of party. At the 13th Congress, held on July 3–9, 1937, there were 34,211 members and 12,906 candidates (a total of 47,117 people). A year later, at the 14th Congress held on July 7–14, 1938, the number of members had decreased to 32,135 and the number of candidates to 12,494 (44,629 people in total). However, after the Great Purge, the number of ACP members suddenly started to increase. At the 15th Congress on February 25 – March 1, 1939, the number of party members had already reached 56,548.

Shamakhi case

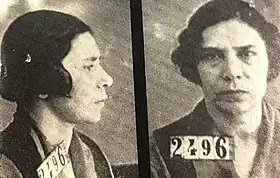

The hearings on the Shamakhi case began on October 27, 1937, and lasted until November 2. Hamid Sultanov was the main accused in this trial.[70] He was an Azerbaijani revolutionary and a member of the Central Committee of the Hummet organization. He also served as the People's Commissar of Internal Affairs of the Nakhchivan ASSR. His wife, Ayna Sultanova, was one of the first revolutionary women of Azerbaijan and served as the People's Commissar of Justice. Ayna Sultanova's brother, Gazanfar Musabekov, worked in the administration of the republic and served as the Chairman of the Council of People's Commissars of the TSFSR.

Along with Hamid Sultanov, there were 13 people on the dock, including Khalfa Huseynov, the First Secretary of the Shamakhi District Communist Party; Israfil Ibrahimov, the former Chairman of the Shamakhi Executive Committee; Aram Avalov, the Second Secretary of the Shamakhi District Communist Party; Ahmad Amirov, the district prosecutor; Alisahib Mammadov, the Director of the Shamakhi State Wine Farm; Georgi Yurkhanov, the head of the district land department; Aghalar Kalanterov, the chief veterinarian of the district; Mammad Mirza Heybaliyev, the head of the road department; Mirali Tanriverdiyev, the head of kolkhoz; Siraj Jabiyev, the warehouseman of kolkhoz; Ali Sadigov, the secretary of the party committee of kolkhoz; Babali Bakirov, the chairman of the village council; and Mammad Huseynov, a village resident.[70]

Hamid Sultanov admitted that he, along with Ruhulla Akhundov, Sultan Majid Afandiyev, Gazanfar Musabekov, Ganbay Vazirov, Dadash Bunyadzade, G. Safarov, and Ayyub Khanbudagov, was a member of the "counter-revolutionary nationalist center". The purpose of the center was to overthrow the Soviet government and separate the Azerbaijan SSR from the USSR in order to restore capitalist property. The center was making preparations for terrorist acts against party leaders and the government, damaging the national economy, and engaging in espionage. Akhundov was appointed as the head of this center, and the leaders of the Shamakhi district were responsible for carrying out its work. The other accused individuals gave similar statements. [70]

The court sentenced nine people to death, including Hamid Sultanov, Khalfa Huseynov, Israfil Ibrahimov, Ahmed Amirov, Aram Avalov, Georgy Yurkhanov, Alisahib Mammadov, Aghalar Kalantarov, and Mammad Huseynov.[71] The others were sentenced to deportation to labor camps for 8–20 years.[71][72] None of Hamid Sultanov's comrades-in-arms survived.[52]

Aliheydar Garayev case

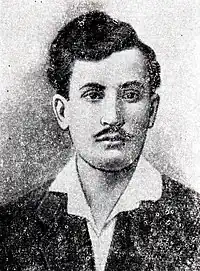

Aliheydar Garayev was a famous figure in the regime and the party. He had been a member of the Menshevik and Bolshevik factions of "Hummat", the Menshevik Parliament of Georgia, and the Musavat Parliament. He later served as the Commissar of Justice and Labor, and then of Naval Affairs. He was also a member of the Provisional Revolutionary Committee of the Azerbaijan SSR. He held leading positions in the Azerbaijan Communist Party,[73] the South Caucasus, and the Soviet Union until the late 1920s. He also worked as the night shift director of the History Department at the Institute of Red Professors, and as the head of the Eastern Department of the Comintern.

As the secretary of the republic's Central Committee in 1928–1929, he tried to stop Baghirov's anti-party actions and brought them up to the ACP Central Committee's advisory board and the Transcaucasian State Committee. Mir Jafar Baghirov, in turn, wrote complaints about Aliheydar Garayev and sent copies to Beria.[74]

In 1936, Baghirov asked Yezhov to prosecute Garayev, citing negative reviews of Garayev's book "From the Near Past", published in 1926 in the "Party Worker of Transcaucasia" journal. Baghirov also claimed that Garayev had hidden his Menshevik affiliation. The Communist Party's collegium discussed this issue on February 3, 1937, but found the accusation false and the concealment unfounded.[74]

However, a few months later, Garayev and his wife were arrested in Moscow and taken to Baku at the request of the Azerbaijan SSR NKVD.[74] He faced various charges, from hiding his Menshevik past to leading a counter-revolutionary nationalist group. Garayev was also accused of initiating the secession of the Azerbaijan SSR from the USSR, harming the state and Baghirov, and planning sabotage and terrorism.[74] Garayev implicated Mamia Orakhelashvili, Ruhulla Akhundov and others, but later withdrew his statements and called them false in court. On April 21, 1938, he was executed by firing squad.[74][75]

The repressions were a tragedy for the Garayev family. Garayev's wife, Khavar Shabanova-Garayeva, was acquitted and released only in 1954. His brother Alovsat Garayev escaped to the Far East and wrote his memoirs before he died. He wrote in "Bakinsky Rabochi" newspaper:

Of the 11 members of the Garayev family (mother, father, seven brothers and two sisters), only two brothers survived, the rest were killed, died or became disabled. Their remains were scattered over the large country, but we managed to gather them and bury them in Baku. Next to my parents' graves, there is a symbolic grave for my brother Aliheydar. In that grave, not his remains, but the sacred soil from our great-grandfather's grave, was buried.[76]

Nazim Garayev, son of Alihaydar Garayev, was also among those who were stigmatized as being the son of a traitor.[77]

Repressions in economic system

.jpg.webp)

In 1938, Baghirov ordered the arrest of several officials of the Azerbaijan SSR such as Manaf Khalilov,[78] the first deputy of the Council of People's Commissars; Ibrahim Asadullayev,[79] the people's commissar of internal trade; Abulfat Mammadov,[80] the people's commissar of agriculture; Iskander Aliyev,[81] the people's commissar of light industry; Yefim Rodionov,[82] an official of the people's commissariat; and Lyuborski-Novikov,[83] a staff member of the Council of People's Commissars. Baghirov's accomplices falsely accused them of being the leaders of a "Reserve Rightwing Trotskyite Center of the Counterrevolutionary Nationalist Organization" (RRTCCNO). They tortured and coerced these people into making false statements against many other innocent people.[84] All the prisoners, except for Lyuborsky-Novikov, were deputies of the 1st convocation of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR (chamber of nations). In 1939, after the investigation had subsided, they retracted their earlier statements made under torture.[85] As a result, several investigations were carried out on this case, and in 1941, they were all sentenced to long prison terms for allegedly damaging enterprises with counter-revolutionary intentions. Khalilov, Asadullayev and Rodionov died in the prison camps. In April 1955, all those involved in this case were acquitted. Iskander Aliyev came back to Baku in 1956 after spending 18 years in prison and exile in Kazakhstan. He testified against Baghirov and his accomplices as one of the main prosecution witnesses in the trial held in April.[85] The case and names of leaders of RRTCCNO were mentioned in the verdict issued by the court against Baghirov and his accomplices.

Repression of intellectuals

From 1920 to 1930, Baku served as the cultural center for all Turkic peoples.[86] Many intellectuals from Tatarstan, Uzbekistan, Crimea, and Turkey lived and worked there. It can be said that almost most of them were killed as a result of these repressions.[86] According to American historian Tadeusz Swietochowski, intellectuals were the primary victims of repression, with 29,000 being sentenced to death. As he noted, "intellectuals with a sense of historical mission and social power had lost their existence".[60]

Poets and writers

In 1937–1938, Azerbaijani literature suffered the most from repression in Transcaucasia. Among those subjected to repression, writers who had established themselves before the revolution predominated. However, a group of writers who had formed during the Soviet period were also subjected to repression.[87]

On May 17, the "Communist" and "Bakinski Rabochi" newspapers published articles against poets Ahmad Javad and Huseyn Javid, as well as writers associated with Mussavatists, Pan-Turks, and nationalists.[88] On the night of June 4, 1937, Ahmet Javad, Mikayil Mushfig, Huseyn Javid, Haji Karim Sanili,[89] and Atababa Musakhanli were arrested.[90]

Articles against poets and writers were published in newspapers such as "Adabiyyat", "Genc Isci", "Yeni Yol", and magazines such as "Hucum" and "Inqilab ve medeniyyet". On June 20, 1937, the "Communist" newspaper, Sunday No.141 (5069), published a commissioned article entitled "The remains of the enemy in literature should be exposed to the end":

For many years, M. Mushfiq has openly or secretly opposed our socialist structure and continued his subversive activities. All remnants of the enemies of the people in literature should be exposed to the end, and those rabid Trotskyists who harbor misguided hatred and enmity against our great socialist structure should be eliminated

In the June 9, 1937, edition of the "Adabiyyat" newspaper, No.25 (110), Jafar Khandan wrote in his article titled "Let's Clean Up Our Ranks":

The hypocritical policies of Javid, Javad, Mushfiq, Sanil, and others, who are enemies of the people, force us to be even more vigilant and ruthless in our fight against such hidden enemies.

The article titled "There is No Place for Enemies in Our Ranks" written by Agahuseyn Rasulzade, states:

People such as Huseyn Javid, Mikayil Mushfiq, Simurgh, and Gantamir have promoted counter-revolutionary nationalism in their works through various veils and phrases.

The author of the article titled "Must Be Ruthless" published in the "Adabiyyat" on June 9, 1937, wrote:

The facts show that we have done very little to clear our front of enemies and enemy influences. Counter-revolutionaries such as Javid, Javad, and their disobedient student Mushfiq, who have been hiding under the guise of "Reconstruction" for a long time, have deceived us and lived on the literary front with false and deceitful promises. They have caused great damage to the work of socialism. These counter-revolutionaries have always tried to spread the poison of counter-revolutionary conformity in the literary environment through their actions and non-original "works".

In January 1940, an arrest warrant was issued for writer Yusif Vazirov, also known as Chamanzaminli, based on statements from several individuals who had been subjected to repression. Back in 1937, Vazirov was expelled from the Azerbaijan Writers Union and dismissed from all his positions for his novel "Students". As a result, Vazirov was forced to move to Konye-Urgench, where he taught at the Institute of Teachers. In 1940, Vazirov was arrested and brought to Baku. He was sentenced to 8 years in a correctional labor camp for participating in a counter-revolutionary Musavatist-nationalist organization and for carrying out pan-Turkic and Trotskyist propaganda.[91] He died on January 3, 1943, in the Unzhlag camp at the Sukhobezvodnoye station.[92][93]

Taghi Shahbazi Simurg, a writer and former rector of ASU, was arrested in July 1937. He was accused of being a "member of a counter-revolutionary nationalist organization." On January 2, 1938, Shahbazi was sentenced to the highest punishment and executed on the same day.[94][95]

At that time, almost half of the members of the Azerbaijan Writers Union were subjected to repression. Among them were Sultan Majid Ganiyev, Omar Faig Nemanzadeh, Mammad Kazim Alakbarli, Said Huseyn, Amin Abid, and others.

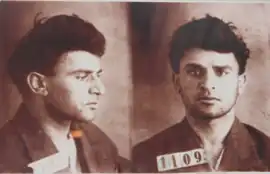

Mikayil Mushfig case

Mikayil Mushfig was also among those subjected to repressions.[96] On 27 May 1937, a report by the NKVD, written by captain Chinman, stated that "Mikayil Mushfig is currently in contact with the Musavat youth organization and does not hesitate to slander the party and the government."[97] Additionally, the report alleged that Mushfig sought to incite discontent among the people with inflammatory statements such as "Azerbaijan does not have its own freedom; it lives in a Russian colony." The written confessions of the arrested defendants were also considered. According to the investigator's report, a warrant, number 508, was issued in Mikayil Mushfig's name on June 3. He was subsequently arrested at his home on Friday, June 4.[98]

Mikayil Mushfig was arrested and his house was searched by employees of the State Security Department: Mustafayev, Petrunin and Shevchenko, the chairman of the Central Executive Committee. During the search, they confiscated 14 books published in Turkey, 5 books from other publishers, 4 different Turkish magazines, 6 Iranian publications, 14 photographs, passport, military identity card, manuscripts, and other items. The manuscripts included Mirza Abdulgadir Vusagi's poetry divan, opera librettos, verse tales, hundreds of Mushfig's poems, the manuscript of a verse drama he was working on for the Turkish-drama theater, letters, and Dilbar Akhundzade's (his wife) notebook named "Dilbarnama". The confiscated items were burned on October 13, 1937.[99]

According to his recollections, he wholeheartedly accepted the existing structure. As per the memoirs of Azerbaijani writers, his work "Stalin" was considered "the most powerful poem written about Stalin in his time".[100] His first investigation took place on June 5, 1937. Sergeant G. B. Platonov, the operational commissioner of the IV division of the 4th department, conducted the investigation. The investigation report noted:

On June 5, 1937, I, Sergeant G.B.Platonov, the operational commissioner of the IV division of the 4th department, conducted an investigation on the defendant Ismayilzade Mikayil Mushfig Gadir oglu. He was born in 1908 and resides at 108 Nizhno Priyutskaya Street. His nationality is Azerbaijani and he holds a passport valid for five years, JAA N543214. He works as an editor and translator at the Azerbaijan State Publishing House and is a member of the Union of Soviet Writers of Azerbaijan. His father was a teacher who passed away in 1914. Before and after the revolution, he was a student and a servant starting from 1927. Active family members include his wife, Dilbar Akhundzade, who is 23 years old and a student at the Azerbaijan Medical Institute, and his brother Mirza, who is 32 years old and works as an accountant. He is highly educated and politically neutral. He has not been involved in any investigation or prosecution before or after the revolution. Since 1929, he has received two prizes in the republican literature competition. He attended the student meeting of the Red Army.[99]

During the interrogation, he was questioned about his alleged membership in a counter-revolutionary organization and his supposed counter-revolutionary nationalist stance. But he denied these allegations.[99]

He was tortured while in prison. Initially, his fingernails and toenails were removed. He was then confined in a special chamber with a well, where he was kept for two days in water with rats in a hoop. After two nights, they scattered broken glass on the floor of his solitary cell and forced him to walk barefoot. Despite the torture and confrontations with others, he did not betray anyone.[99]

During the investigation, Mushfiq was coerced into stating that his school teacher had been influenced by the counter-revolution and that he had been friends with nationalist writers.[101] He was sentenced and executed on January 5, 1938.[102][103]

Ahmad Javad case

Ahmet Javad, a poet, translator, member of AWU, and professor, is known for writing the lyrics of the Azerbaijani national anthem. After the establishment of the Soviet government, he served as the head of the Department of Public Education in Guba from 1920 to 1922. He was a teacher, associate professor, and head of the department of Azerbaijani and Russian languages at the Azerbaijan State Agricultural University in Ganja from 1930 to 1933. He worked as an editor in the translation department of the Azerbaijan State Publishing House in 1934 and headed the documentary film department at "Azerbaijanfilm" from 1935 to 1936. However, articles and denunciations written against him during these years led to his arrest on multiple occasions.

At one point, he was a member of the Musavat party. In 1923, he was arrested on charges of secret activity against the state and having a special role in the abduction of Mirzabala Mammadzadeh abroad. Later that same year, he was released under declaration. In 1925, a group of his colleagues labeled his poem "Göy-göl" as counter-revolutionary, leading to his imprisonment.[104][105]

In this poem, he was accused of talking about celestial bodies such as star and moon, and conveying a message to the Musavatists. The translation of the poem was sent to Moscow, and after that Baku was informed that no violation was found in the poem. Consequently, local administration officials were compelled to release him from prison.

In 1928, his poems were featured in "Istiqlal Majmuesi", a publication by Musavatists in Turkey. Some of Ahmet Javad's colleagues, who were seeking a pretext for his arrest, exploited this opportunity. They relentlessly criticized him in the press for his poems published in "Istiglal Jammuasi". In response, Javad addressed the accusations in an article titled "I strongly protest", which was published in the October 31, 1929, issue of the "Communist" newspaper: "Just as I am unaware of this book, which was published by an organization with which I have no affiliation following the April revolution, I am equally uninformed about which parts of my work were included in it." Javad was subjected to insults in both signed and unsigned articles and poems published in newspapers. He faced opposition at various times, with articles such as "We Must Expose Until the End" (Abdulla Faruq), "There is No Place for Enemies in Our Ranks" (Agahuseyn Rasulzade), "Let's Clean Our Ranks!" (Jafar Khandan), "Cleaning Must Begin!" (Mammed Said Ordubadi), "Must Be Ruthless!" (Mir Jalal), "About Our Mistakes" (Samad Vurgun), and "Where Alertness Fades" (Seyfulla Shamilov) being written against him.[106]

In March 1937, despite being awarded first prize for his translation of Shota Rustaveli's "The Knight in the Panther's Skin", he was arrested on June 4. His initial interrogation was conducted by Agasalim Atakishiyev, the head of the IV Department of the KGB, on June 5, 1937. Javad was questioned about his alleged counter-revolutionary activities, his affiliations, his membership in the illegal party known as Musavat, his authorship of anti-government poems, and his involvement in nationalist activities. Ahmet Javad, in his defense, acknowledged that he was a member of Musavat and had engaged in the propagation of counter-revolutionary nationalism. However, he claimed to have abandoned these activities following his arrest in 1923. During his third interrogation on September 20, 1937, Javad officially confirmed his participation in the Balkan War. The NKVD investigator, curious about Javad's connections with Iran and Turkey, asked, "Have you been abroad? If so, when and where?" In response to this question, he said:[107][108]

Yes, I traveled to Turkey in 1912 to volunteer for the Turkish army during the Turkish-Balkan war. I obtained a Persian passport from a Greek individual in Batumi who was involved in some form of passport trade. I was accompanied by I.Akhundzade, Ali, and I. Alizade, all of whom intended to join the Turkish army. We were all accepted into a volunteer group and participated in military operations against the Bulgarians. I returned to Russia in autumn of 1913.

On September 25, 1937, the indictment was prepared by the head of the 4th department of the NKVD SSD of the Azerbaijan SSR, Sinman and Klementich. Approved by Sumbatov, it justified the need to prosecute Ahmed Javad as follows:[109][110]

Ahmad Javad Akhundzadeh has been a Musavatist cadre since 1918. Despite the overthrow of the Musavat government, Akhundzade maintained his counter-revolutionary stance. Not only was he elected a member of the secret Musavat party, but he also became extremely close to its central leadership. In 1922–23, Akhundzade was elected a member of the illegal Baku committee of Musavat. When arrested by the Cheka in 1923, Akhundzade concealed his membership in the Musavat party and his counter-revolutionary activities from the investigation. After his release from prison, he claimed to have distanced himself from that party, but for several years he propagated counter-revolutionary Musavat ideas in his works. From 1920 to 1923, he was a member of the first secret committee of the Musavat Central Committee, leading to his arrest in 1923 and subsequent release with a declaration. Despite this, he did not abandon his Musavatist positions and continued his secret work for Musavatism, propagating its spirit to young Azerbaijani poets who gathered around him. Ahmet Javad slandered the party and government leaders of the republic and their counter-revolutionary position on national policy. He participated in the work of the counter-revolutionary bourgeois nationalist organization, joined an existing rebel provocation-terrorist-sabotage nationalist organization in Azerbaijan, committed acts of terrorism against Soviet government leaders, spied for capitalist countries, aimed to overthrow the Soviet government and separate Azerbaijan from the USSR.

Thus, the Mobile Session of the Military Collegium of the Supreme Court of the Soviet Union charged him under Articles 69, 70, and 73 of the Criminal Code of Azerbaijan SSR.[108][109] The proceedings commenced on October 11. The court was presided over by Matulevich, with Zaryanov and Zhigur serving as members. The military jurist Kostyushko and the chief assistant of the USSR prosecutor, Rovsky (Rozovsky), were also in attendance.[109] The protocol states: "The defendant fully acknowledged his guilt, corroborated the statements made during the preliminary investigation, and indicated that he had no additional information to contribute to the court investigation".[108] However, there were no defenders such as lawyers or witnesses, present at the trial.[109] The verdict was read on October 12, 1937, based on the charges brought against him. The trial, which commenced on October 12, lasted a mere 15 minutes. He was executed that night.[107][108][109][110][111][112] On same night, another writer Buyukaga Talybli was also executed alongside Ahmet Javad.

The special issue of the "Sarhad" newspaper (Baku, 1999, No. 1) describes his execution as follows: "On the night of October 12–13, a total of 46 people were executed. Among those people was Ahmad Javad, whose name is 14th on the list."[108]

There are varying accounts regarding the his death in different sources. For instance, Mahammad Amin Rasulzade, in his work "Contemporary Azerbaijani Literature", postulated that Ahmad Javad died in Siberia, just like Huseyn Javad. This Siberian theory was also supported by the emigrant researcher Huseyn Baykara. However, the poet's eldest son, Niyazi Akhundzade, offered a different perspective on his father's demise:[108]

In 1956, during the trial of Mir Jafar Baghirov, an employee of the prosecutor's office named Shevtsov, who had arrived from Moscow, inquired of CSS General A. Atakishiyev about the "service" he had provided in the trial of Ahmad Javad. Atakishiyev responded that he could not recall the events. Following this, Shevtsov said: "He died from torture."

In addition, Akhundzade also said:[107]

Government officials told us that my father was sent into exile without the right to correspond because he was a political prisoner. But don't say they killed my father in Baku, in the basement of the NKVD, by beating him to death. We found out about this much later.

However, official documents reveal that Ahmad Javad was arrested on June 4, 1937, and was executed in Baku on the night of October 12–13 that same year, without being deported to any other location.[113]

Huseyn Musayev, who knows Ahmet Javad from their time together in Guba where Javad worked as a teacher, was among those who vouched for the his acquittal in 1956. Other guarantors included notable figures such as director Alexander Tuganov, economist Husyu Mamayev, and actor Agahuseyn Javadov.[108]

In 1955, a meeting presided over by Justice Colonel Senin, a representative of the Military Collegium of the Supreme Court, resulted in the adoption of special decision No. 4P-014316 in relation to the criminal case of Ahmed Javad. This decision led to the suspension of the criminal case. The decision revealed that the criminal case had been falsified and it was clear from the case files that the he did not die under torture, but was executed following a court decision. Consequently, Ahmed Javad was posthumously acquitted in 1955.[107][112]

His wife Shukriya Khanim was exiled to Kazakhstan for 8 years because she was a "family member of a traitor."[114]

Huseyn Javid case

Huseyn Javid achieved recognition as the foremost exponent of modern Azerbaijani Romanticism during the initial decade of his career.[115] Russian historians such as Ashnin, Alpatov and Nasilov believe that Huseyn Javid was the most influential among the writers imprisoned at that time.[116] In the 1920s, newspapers described him with phrases such as "the most famous and well-known poet of Caucasus" and "Azerbaijan's most influential poet".[117] He was arrested on charges such as "maintaining counter-revolutionary connections", "engaging in friendly discussions with several Musavatists", and "gathering young poets with nationalist leanings around him and nurturing them in the spirit of Musavatism".[90] He asserted his innocence, yet the first and second sessions of the tribunal were unable to reach a verdict on his case, resulting in his continued imprisonment.[118] In the spring of 1938, with the appointment of new leadership for the NKVD of Azerbaijan, Huseyn Javid was convicted under Articles 72 and 73 of the Criminal Code of the Azerbaijan SSR.[118]

The case they sent to the Special counsel in Moscow was not examined, and it was subsequently returned to Baku. Upon re-examination of the case in Baku, Article 68 (espionage) was added to the charges.[118] According to the final indictment, it was established that he had resided in Turkey for an extended period, and later in Germany. As per the NKVD's information, he was implicated in espionage activities.[119] On June 9, 1939, he was sentenced to eight years in a correctional labor camp. Notably, the charge did not include an espionage clause. Huseyn Javid passed away in 1941. Rehabilitation efforts revealed that he died in the Tayshetsky District of the Irkutsk Oblast.[119][120]

Scientists

Repressions in the USSR Academy of Sciences' Azerbaijani branch

Repressions in the USSR Academy of Sciences' Azerbaijani branch and the university began in December 1936, starting with the arrest of Ruhulla Akhundov.[121] By January 1937, several Azerbaijani scientists, including Hanafi Zeynalli, Vali Khuluflu, and Bekir Chobanzade, had been arrested.[122] Bekir Chobanzade was arrested at a sanatorium in Kislovodsk and transported to Baku in a special convoy.[58] On the night of March 18, the historian Gaziz Gubaydullin was also taken into custody. Following his arrest, Mir Jafar Bagirov published a critical article about him in the "Bakinski Rabochi" and "Communist" newspapers.[122] During the plenum of the Central Committee of the Azerbaijan SSR on March 19–20, Mir Jafar Baghirov addressed the nationalist work led by Ruhulla Akhundov on the cultural front. He declared that professors Bekir Chobanzade and Gaziz Gubaidullin were the leading representatives of Pan-Turkism in Azerbaijan.[123] Khalid Said Khojayev was arrested on the night of June 4.[124]

Critic and literary critic Hanafi Zeynalli was a close friend of Ruhulla Akhundov.[125] Prior to his arrest, he served as a researcher and secretary at the Institute of Language and Literature of the USSR Academy of Sciences' Azerbaijani branch.[126] Turkologist Veli Khuluflu, who was Ruhulla Akhundov's deputy and also headed the history department at the Azerbaijan branch of the USSR Academy of Sciences, was another key figure.[127] Orientalist Bekir Chobanzade was originally a Crimean Tatar.[128] In the 1920s he served as a member of the Crimean Central Executive Committee and was one of the leaders of the Crimean Tatar party, "National Faction".[128] In 1925, he relocated to Baku and, until early 1937, held the position of professor at Baku State University and worked for the Azerbaijan branch of the USSR Academy of Sciences.[128] Professor Gaziz Gubaidullin, the first Tatar historian, is renowned for his fundamental studies on the history of Turkic peoples.[129][130] Khalid Said Khojayev, an Uzbek Turkologist, worked as a researcher in the history department of the Azerbaijan branch of the USSR Academy of Sciences.[131][132]

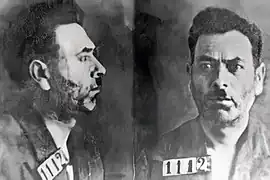

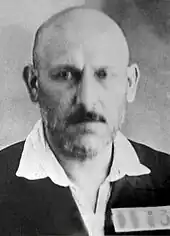

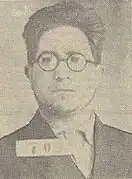

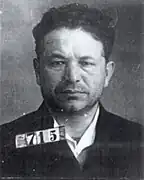

Hanafi Zeynalli

Hanafi Zeynalli

(1896–1937) Vali Khuluflu

Vali Khuluflu

(1894–1937) Bakir Chobanzade

Bakir Chobanzade

(1893–1937) Gaziz Gubaydullin

Gaziz Gubaydullin

(1887–1937).jpg.webp) Khalid Said Khojayev

Khalid Said Khojayev

(1893–1937).jpg.webp) Aleksandr Bukshpan

Aleksandr Bukshpan

(1898–1937).jpg.webp) Bala bey Hasanbeyov

Bala bey Hasanbeyov

(1899–1937) Alirza Atayev

Alirza Atayev

(1898–1962) Zinnet Zakirov

Zinnet Zakirov

(1904–1938)

During the investigation, Bekir Chobanzade testified about the existence of a pan-Turkic "All-Union United Center", which was reportedly established in 1934.[133] The center was headed by Turar Ryskulov, the Deputy Chairman of the Council of People's Commissars of the RSFSR. Other members included Sanjar Asfendiyarov, a professor and former director of the Moscow Institute of Oriental Studies; Aliyev, the Chairman of the Karachay-Cherkessia Province Executive Committee; Dagestan intellectual A. Takho-Godi; Gaziz Gubaidullin; and Bekir Chobanzade himself. Chobanzade admitted that he did not personally know most of the individuals he named, but he had met some of them years ago.[134] In July, he testified about leading Turkologist academician Aleksandr Samoylovich, who was subsequently arrested. This testimony contributed to the formation of a court case concerning a large "all-union, counter-revolutionary, rebel, pan-Turk" organization.[133]

Gaziz Gubaidullin is alleged to be "one of the main ideologists of pan-Turkism in the USSR".[135] He was accused of "committing harmful acts at production sites in Azerbaijan" and espionage, purportedly for Turkish, Japanese, and German intelligence.[135] Bekir Chobanzade was charged under articles 60, 63, 70, and 73 of the Criminal Code of the Azerbaijan SSR.[136] Although Khalid Said Khojayev was not named among the leaders of the organization, he was accused of being a member of the organization and simultaneously an "old Turkish intelligence officer".[124]

The troika that arrived in Baku consisted of military corps lawyer Ivan Osipovich Matulevich (chairman), military brigade lawyer Zyryanov, and Zhiguradan, along with the secretary, first-rank military lawyer Kostyushka.[137] They were accompanied by the chairman of the USSR prosecutor's office, military corps lawyer R.S. Rozovsky.[137] Bekir Chobanzade, Gaziz Gubaydullin, Hanafi Zeynalli, Huseynali Bilandarli,[138] Tikhomirov[139] (rector of the Institute of Party History and dean of the Faculty of History of ASU), Bukshpan,[140] Khalid Said Khocayev, Abdulaziz Salamzade,[141] and Balabey Hasanbayov[142] attended the court proceedings from October 11–13.[137] Prominent scientists and party leaders such as Mirza Davud Huseynov and Mammad Juvarlinski were sentenced to death. Those sentenced to death during these proceedings were executed on October 13, 1937, the last day of the trial.[137]

Other scientists

Literary experts Salman Mumtaz, a writer, and Ali Nazem, a researcher at the Language and Literature Institute of the USSR Academy of Sciences' Azerbaijani branch, were sentenced to 10 years in prison. Salman Mumtaz was executed in Orlovsky prison in 1941.[143] According to some reports, Ali Nazem also died in the same year.[144] However, another source suggests that he was executed in 1941.[145]

Mikayil Rafili, an Azerbaijani poet and historian, was accused of "promoting counter-revolutionary Pan-Turkist ideas in literature, opposing Azerbaijani national creativity, and supporting Western trends" and expelled from the Union of Writers.[146] Rafili was also accused of being a member of the "All-Union United Center" established in 1934. However, he was later released in 1939.[146][147]

In late 1937, Alasgar Alakbarov, the first Azerbaijani ethnographic archaeologist[148] and the founder of the science of archaeology and ethnography in Azerbaijan,[149] was arrested.[150] He served as the head of the archaeology department of the Azerbaijan State Research Institute and the head of the History of Material Culture Department at the Institute of History, Archaeology, and Ethnography of USSR Academy of Sciences' Azerbaijani branch.[150] Ivan Meshchaninov once wrote about Alakbarov, stating that he was "unquestionably one of the best connoisseurs of country".[151] Alasgar Alakbarov passed away in prison in 1938.[150][152]

Gulam Bagirov, linguist and deputy director for scientific affairs of the Institute of Language and Literature of the USSR Academy of Sciences' Azerbaijani branch, was also arrested. He was sentenced to eight years in a correctional labor camp.[153] Agamir Mammadov, a scientific employee of the USSR Academy of Sciences' Azerbaijani branch and the director of the Azerbaijan State University-based library, was accused of "counter-revolutionary activity, pan-Turkism, and Trotskyism" and executed in 1938.[150][153][154]

Idris Hasanov, a candidate of philological sciences and linguist, also subjected repression. He served as a professor at the Azerbaijan Pedagogical Institute and USSR Academy of Sciences' Azerbaijani branch.[155] In the autumn of 1937, Hasanov assumed the role of director of the Institute of History, Language, and Literature of the USSR Academy of Sciences' Azerbaijani branch.[156]

Idris Hasanov's arrest was prompted by statements made by Bekir Chobanzade, Veli Khuluflu, and Abdulla Sharifov, the head of the department at the Azerbaijan Pedagogical Institute, as well as a letter written from his workplace. In response to an inquiry about Idris Hasanov sent to the USSR Academy of Sciences' Azerbaijani branch, Aleksey Klimov, the director of the Institute of History, Language and Literature, and Guliyev, the new director of the language department, stated that:

We answer your question about the former deputy director of the Institute, Idris Hasanov, as follows: Idris Hasanov has been doing pan-Turkist propaganda and damaging work in the field of Azerbaijani linguistics for a long time. He began to spread his pan-Turkist propaganda from the very first line of his first work, "Derivation of Nouns without Attributive Suffixes in the Dialect of the Ganja Population", published in 1926. All his thoughts and opinions are a continuation of the pan-Turkic-Musavatist ideas about the Turkish language, which is the successor of the "unified ancient Turkic languages". Hasanov, who is committed to the pan-Turkist idea, said that he intends to apply Ottoman forms to the grammar of the Azerbaijani language. In addition, in the Azerbaijani language, he called Russian and international words barbarism and "foreign" words. Quoting from the text of "Azerbaijani workers' letter to Stalin", Hasanov notes that "Azerbaijani language was almost expelled from Azerbaijani schools". The language cannot be considered a gross distortion. This is counter-revolutionary sedition and slander! While the spelling of the Azerbaijani language was being developed, Hasanov, together with other traitors, tried to fill our language with Arabic, Persian and Ottoman words, thereby promoting the culture of the West and capitalist countries. He also worked from a position of loss in the training of teachers for Azerbaijan State Pedagogical University

On June 2, 1939, Idris Hasanov was sentenced to eight years in a correctional labor camp due to his involvement in an anti-Soviet organization.[159] Despite suffering a heart attack in Kolyma, he managed to survive. Upon completing his sentence on April 3, 1946, he returned to Ganja and resumed his career as a teacher at school. However, according to secret instructions signed by Beria in 1948, survivors like him were re-arrested, sentenced, and exiled permanently. Consequently, on December 21, 1949, he was once again detained as a "dangerous element" based on the charges from 1939 and was exiled for life to the Krasnoyarsk region.[160] On November 3, 1950, he committed suicide by throwing himself into the sea.[161]

Linguist Gulam Bagirov faced a fate similar to that of Idris Hasanov. He served as the head of the language department in USSR Academy of Sciences' Azerbaijani branch from 1933 to 1935, and later became the deputy director for scientific affairs at the Institute of Language and Literature of the same branch. During his tenure as deputy, Artur Zifeld-Simumyagi was the director. Bagirov shared a ward with Bekir Chobanzade when the latter was arrested in Kislovodsk. Upon his return to Azerbaijan, Bagirov was dismissed from the institute and expelled from party ranks. He was arrested on April 4, 1938. During his investigation, he testified that Vali Khuluflu had involved him in counter-revolutionary activities in 1936, although Vali Khuluflu did not implicate him in any statement.[162]

In 1939, Gulam Bagirov was sentenced to eight years in a correctional labor camp but managed to survive in Kolyma. He returned to Azerbaijan in 1947, but was not permitted to live in Baku. Consequently, he was compelled to work as a secretary in the health department of the Lachin region from 1947 to 1948. Similar to Idris Hasanov, he faced renewed accusations based on old charges during the second wave of post-war repression. As a result, he was exiled for life to the Jambyl Province of Kazakhstan in 1949. There, he worked as a teacher of Russian language and literature in local schools. In 1956, he was acquitted and allowed to return to Baku.[163][164]

Artists

On March 17, 1938, Azerbaijani pianist Khadija Gayibova, founder of the Baku Eastern Conservatory was accused of being a member of a counter-revolutionary organization and arrested.[165] Her husband, Rashid Gayibov was arrested alongside him as "enemy of the people".[166] The reason for Khadija Gayibova's arrest was the statements made by Farajzade under torture. During the period of the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic (ADR) and the Soviet government, foreign guests, Turkish officers, and individuals like Dadash Bunyadzade and Köprülüzade would gather for musical evenings at her house. In 1937, these musical nights became politically significant. Additionally, the brother of Gayibova's first husband worked as a secretary in the representative office of the ADR government in Istanbul. Gayibova was sentenced to death and executed in October 1938. She was posthumously acquitted in 1957.[167][168] Sergey Georgiyevich Paniyev, the head of the music department at the Baku Russian Workers' Theater, was among the artists who were repressed. Paniyev was arrested and accused of counter-revolutionary activities due to the anecdotes and jokes he told about Stalin. The investigation report about his arrest noted that Paniyev consistently expressed anti-Soviet and anti-revolutionary ideas. In 1936, he reportedly gave money to a bartender in the dining room of the "New Europe" hotel and said "Go kill Stalin." The report also mentioned that Paniyev's counter-revolutionary actions influenced other actors in the theater. A few days before his arrest, Paniyev was expelled from the Composers Union of Azerbaijan and dismissed from his job in the theater. Consequently, he was sentenced to six years in prison and was only acquitted in 1989.[167][169]

Actors were also subjected to repression. For instance, in 1937, Ulvi Rajab was arrested as "enemy of the people" and executed.[167][170]