| Stalag IX-B | |

|---|---|

| Bad Orb, Hesse | |

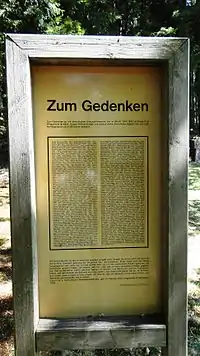

Memorial to Soviet POWs who died at Stalag IX-B | |

Stalag IX-B | |

| Coordinates | 50°12′36″N 9°23′52″E / 50.21009°N 9.39789°E |

| Type | Prisoner-of-war camp |

| Site information | |

| Controlled by | |

| Site history | |

| In use | 1939–1945 |

| Battles/wars | World War II |

| Garrison information | |

| Occupants | Allied POW |

Stalag IX-B (also known as Bad Orb-Wegscheide) was a German World War II prisoner-of-war camp located south-east of the town of Bad Orb in Hesse, Germany on the hill known as Wegscheideküppel. The camp originally was part of a military training area set up before World War I by the Prussian Army.

During World War II, more than 25,000 POWs at a time were housed here. An unknown number of those died. A soldiers' cemetery near the camp holds at least 1,430 dead Soviet POWs, who were treated much worse than soldiers of other nations. Stalag IX-B was also the site of a segregation and removal of Jewish-American troops who, once identified, were transferred to the labor camp at Berga, in contravention of international law. After World War II, the camp served to house ethnic Germans displaced from Poland and the Czech Republic. It eventually reverted to the use it had seen in the 1920s, as a summer camp for school children from Frankfurt. The camp, much renovated and rebuilt, still serves that purpose today.

Camp history

Army training camp

The camp was originally established shortly before the start of World War I to house troops of the German/Prussian Army using the nearby military training area. In October 1913, the Army forced the town of Orb to sell a third of the town forest around the Wegscheide: 1,037 hectares in the areas known as Hoher Berg, Stierruhe, Horst and Bieberer Höhe. However, by June 1913 the first troops of XVIII. Army Corps had already made use of the Truppenübungsplatz Orb. A barrack camp housing up to 9,000 soldiers in training was planned. Lettgenbrunn and Villbach (both today part of Jossgrund) were also evacuated in 1913. After the start of World War I, Orb became a Lazarettstadt ("hospital town") for the injured. From January 1915, Russian prisoners were housed in a camp at Villbach and Lettgenbrunn. After the end of the war, the training area was used to house returning soldiers before demobilization. It was disestablished in 1920.[1][2]

Children's camp

In 1921, the area was rented by Kindererholungsstätte Wegscheide GmbH and the barracks were converted to a summer camp for children. From 1926-29 additional buildings were erected, with financial aid from the lottery and from the wealthy von Weinberg family in Frankfurt.[3]

POW camp in World War II

In August 1939, the summer camp was closed and the Wehrmacht impounded the area. In November 1939, it became the POW camp "Stalag IX-B", housing prisoners from at least eight countries: France, the Soviet Union, Italy, Great Britain, Belgium, Serbia, Slovakia and the United States. The inmates were used as forced labourers in agriculture, forestry and in industry at Gelnhausen, Wächtersbach, Hanau, Offenbach and Frankfurt. There are no data on the number of dead. The first figures on the number of inmates date to September 1941, when the Wehrmacht notified the IRC of 18,483 POWs. After December 1941, Soviet prisoners were first mentioned. The number of prisoners peaked in September 1944 at 25,640 (12,537 French, 11 British, 704 Serbs and Slovaks, 8,448 Soviets and 3,941 Italians). At that point there was severe overcrowding. Inmates later said that around Christmas 1941 about 20 Soviets died each day from hunger and exhaustion.[4] From 5 December 1941 to 22 January 1942, 356 Soviet prisoners died, before the authorities stopped issuing certificates of death. Soviet prisoners were not provided any shelter, given less and worse food than other prisoners, and forced to do hard labour such as quarrying.[5]

From early 1945, following the Battle of the Bulge, approximately 4,700 US infantrymen were held at Stalag IX-B.[6]

In January 1945, the commandant ordered all Jewish prisoners to step forward out of the daily line-up. The senior noncommissioned officer at the camp, Master Sergeant Roddie Edmonds, ordered his men to disobey the order, and told the Germans: "We are all Jews here." For his actions, Edmonds was made Righteous Among the Nations, the first American soldier to be so honoured.[7] After being kept standing for several hours 130 came forward. However, the commandant had been requested to provide 350 for the transport.[8] Thus known "troublemakers" among the prisoners, including PFC J.C.F. "Hans" Kasten, the elected camp leader, were then selected, including anyone who "looked Jewish." On February 8 the group was taken by train to the Berga concentration camp.[9]

An estimated 1,430 Soviet prisoners died here by spring 1942. The dead were buried in mass graves and later moved to the current graveyard around a kilometer from the camp. Today, this site is a memorial to the Soviet dead. A sign lists the names of those 356 dead who are known by name. After the war some of the dead - most of those members of the western Allies' armed forces - were taken home or moved to other memorial sites. Between March 1941 and February 1945, only ten deaths were recorded among the soldiers of the western Allies: 6 Americans, 3 Frenchmen and one Italian.[10]

On 2 April 1945 an American task force broke through the German lines, and drove north over 60 km (37 mi) through enemy held territory to Bad Orb, and liberated Stalag IX-B.[11][12] The camp was liberated by a task force comprising the 2nd Battalion, 114th Regiment, U.S. 44th Infantry Division, reinforced with Stuart tanks and armored cars from the 106th Cavalry Group and M-10 tank destroyers of 776th Tank Destroyer Battalion.

Post-WWII use

In 1945, German POWs and suspected Nazis were held in the camp's more substantial buildings. From the winter of 1945/46 to 1955 the camp was used to house refugees and displaced Germans from what is today Poland and the Czech Republic. At times, these numbered 2,800-3,000. Some of those who died are buried in the Heimatvertriebenenfriedhof nearby. In 1940, the city of Frankfurt had purchased property in the valley of Bad Orb to replace the camp on the Wegescheide. In the summer of 1949, the first children arrived for summer camp at the old location on the hill. In 1952, the area was returned by the town of Bad Orb and in 1955 the final refugees departed.[13]

In 1969, the camp reverted completely to its pre-war role as a vacation camp for school children (mainly from Frankfurt). It currently operates under the name Schullandheim Wegscheide.[14] It is not open to the general public.

The POW graveyard was initially set up with simple wooden crosses by former inmates. In 1955-7, when the graveyard was redesigned, the first sign saying Hier ruhen 1430 sowjetische Soldaten, die von den Faschisten ermordet wurden ("here lie 1430 Soviet soldiers, murdered by the fascists") was removed due to complaints by locals. It was replaced with the sign still there today with the bland inscription: Hier ruhen 1430 sowjetische Soldaten, die in schwerer Zeit fern der Heimat starben ("here lie 1430 Soviet soldiers who died far from home in hard times").[15]

See also

References

- ↑ Peter Georg Bremer (June 2001). Orb-Chronik. BoD – Books on Demand. pp. 41–42. ISBN 978-3-8311-2230-1.

- ↑ Sign posted at Schullandheim Wegscheide, see talk page

- ↑ Hirschmann, Hans (June 2007). "Frankfurter Schulen 1933-1945 Orte der Ausgrenzung" (PDF). Freundeskreis der Auschwitzer Newsletter (in German). 27 (1): 18–28. Retrieved 20 May 2012.

- ↑ Sign posted at Schullandheim Wegscheide, see talk page

- ↑ Sign posted at the memorial, see talk page

- ↑ Uhl, John (2012). "Berga - Soldiers of Another War : Prisoners of War Camps". PBS. Retrieved 20 May 2012.

- ↑ "'We are all Jews': World War II soldier honored for saving lives in POW camp". CNN. Retrieved 11 June 2018.

- ↑ Bard, Mitchell G. (1996). Forgotten Victims: The Abandonment of Americans in Hitler's Camps. Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press. ISBN 0-8133-3064-5. Retrieved 20 May 2012.

- ↑ Kasten, J.C.F. "Hans" (2012). "Personal Narrative: Johann Carl Friedrich Kasten IV". Library of Congress : Veterans History Project. Retrieved 20 May 2012.

- ↑ Sign posted at the memorial, see talk page

- ↑ "Stalag IX Liberation". 2016-03-03. Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2020-09-18.

- ↑ "US Mission to Rescue 6,000 POWs 1945". YouTube. Archived from the original on 2021-12-21.

- ↑ Sign posted at Schullandheim Wegscheide, see talk page

- ↑ "Schullandheim Wegscheide". schullandheim-wegscheide.de (in German). Retrieved 17 August 2015.

- ↑ Sign posted at the memorial, see talk page

External links

- The Lost Soldiers of Stalag IX-B The New York Times Magazine (subscription required)