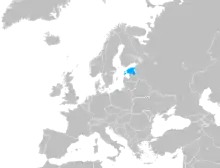

Squatting in Estonia is the occupation of unused land or derelict buildings without the permission of the owner. It is a tactic used by different groups including former factory workers, homeless people, artists and anarchists.

History

On the periphery of Tallinn, the capital of Estonia, workers at the Dvigatel factory were given land in the 1980s to build summer houses. After the factory shut down, the land was forgotten about by the authorities and people started lived there. Some were original residents, some were homeless squatters. In 2017, the nearby airport purchased the land parcels in order to expand and started to evict the site although a few residents had bought their land and pledged to not sell up.[1] In the 1990s, the wooden houses surrounding Tallinn Baltic Station were the domain of squatters.[2]

The Contemporary Art Museum of Estonia was founded as a squat in part of a decommissioned central heating plant in the north of Tallinn. It then legalized in 2009.[3]

Anna Haava

In Tartu, a self-managed social centre was set up at Anna Haava 7a in 2011.[4] The long derelict building was adjacent to the former home of Jaan Tõnisson, who was prime minister in the 1920s, and had previously housed his son. The anarchist squatters repaired the building and set up a free shop and an infoshop.[5] The city council ordered the occupants to leave but they claimed to have permission from Tõnisson's granddaughter to use the house and therefore the city was unable to evict them without the owner's request.[6] The building was then sold and the squatters made an agreement with the new owner to leave by the end of May 2015, as part of which they could stay in the neighbouring house until autumn.[7][8] As of 2020, the building had been redeveloped into eight apartments.[9] In Tallinn after several failed attempts to set up a squatted social centre, anarchists decided to rent a space instead and called it Ülase12.[10]

References

- ↑ Haas, Annika (2017). "Plane Watchers: Evicted in Estonia". Lens Culture. Retrieved 29 March 2021.

- ↑ "What is driving urban gentrification?". The Economist. 16 September 2013. Retrieved 29 March 2021.

- ↑ McLaughlin, Laurel. "Conversation with Marten Esko, Contemporary Art Museum of Estonia (EKKM)". iisforinstitute.icaphila.org. I is for Institute — ICA Philadelphia. Retrieved 29 March 2021.

- ↑ Olmaru, Jaan (28 December 2014). "Pärijad müüvad Jaan Tõnissoni maju". Tartu Postimees (in Estonian). Retrieved 29 March 2021.

- ↑ Teder, Merike (26 December 2013). "Mari-Liis Leis: Anna Haava 7a hõivatud maja lugu". Arvamus (in Estonian). Retrieved 29 March 2021.

- ↑ Olmaru, Jaan (8 April 2013). "Tartu majahõivajad keelduvad välja kolimast". Tartu Postimees (in Estonian). Retrieved 29 March 2021.

- ↑ Olmaru, Jaan (9 June 2015). "Hõivajad kolisid teise Tõnissoni majja". Tartu Postimees (in Estonian). Retrieved 29 March 2021.

- ↑ Olmaru, Jaan (12 May 2015). "Pärijad müüsid Tõnissoni majad maha". Tartu Postimees (in Estonian). Retrieved 29 March 2021.

- ↑ Hanson, Raimu (5 November 2020). "GALERII ⟩ Jaan Tõnissoni kodu võtab vastu külalisi". Tartu Postimees. Retrieved 29 March 2021.

- ↑ Medium, Giz (27 February 2018). "Ülase12: The DIY Punk & Community Space in Tallinn". Retrieved 29 March 2021.