Slavicisms or Slavisms are words and expressions (lexical, grammatical, phonetic, etc.) borrowed or derived from Slavic languages.

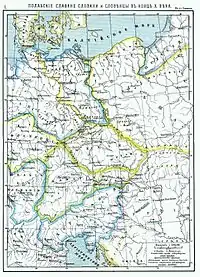

Distribution

Southern languages

Most languages of the former Soviet Union and of some neighbouring countries (for example, Mongolian) are significantly influenced by Russian, especially in vocabulary. The Romanian, Albanian, and Hungarian languages show the influence of the neighboring Slavic nations, especially in vocabulary pertaining to urban life, agriculture, and crafts and trade—the major cultural innovations at times of limited long-range cultural contact. In each one of these languages, Slavic lexical borrowings represent at least 15% of the total vocabulary. However, Romanian has much lower influence from Slavic than Albanian or Hungarian. This is potentially because Slavic tribes crossed and partially settled the territories inhabited by ancient Illyrians and Vlachs on their way to the Balkans.

Germanic languages

Max Vasmer, a specialist in Slavic etymology, has claimed that there were no Slavic loans into Proto-Germanic. However, there are isolated Slavic loans (mostly recent) into other Germanic languages. For example, the word for "border" (in modern German Grenze, Dutch grens) was borrowed from the Common Slavic granica. There are, however, many German placenames of West Slavic origin in Eastern Germany, notably Pommern, Schwerin, Rostock, Lübeck, Berlin, Leipzig and Dresden. English derives quark (a kind of cheese and subatomic particle) from the German Quark, which in turn is derived from the Slavic tvarog, which means "curd". Many German surnames, particularly in Eastern Germany and Austria, are Slavic in origin.

The Scandinavian languages include words such as torv/torg (market place) from Old Russian tъrgъ (trŭgŭ) or Polish targ,[1] humle (hops),[2] reje/reke/räka (shrimp, prawn),[3] and, via Middle Low German, tolk (interpreter) from Old Slavic tlŭkŭ,[4] and pram/pråm (barge) from West Slavonic pramŭ.[5]

Uralic Languages

There are a number of borrowed Slavic words in the Finnic languages, possibly as early as Proto-Finnic.[6] Many loanwords have acquired a Finnicized form, making it difficult to say whether such a word is natively Finnic or Slavic.[7]

To date, a huge number of Slavicisms are found in the Hungarian language (Finno-Ugric in origin). This is due to the fact that the Hungarian language was largely formed on the basis of the Slavic substratum of the former Principality of Pannonia.

Others

The Czech word robot is now found in most languages worldwide, and the word pistol, probably also from Czech,[8] is found in many European languages.

A well-known Slavic word in almost all European languages is vodka, a borrowing from Russian водка (vodka) – which itself was borrowed from Polish wódka (lit. "little water"), from common Slavic voda ("water", cognate to the English word) with the diminutive ending "-ka".[9][10] Owing to the medieval fur trade with Northern Russia, Pan-European loans from Russian include such familiar words as sable.[11] The English word "vampire" was borrowed (perhaps via French vampire) from German Vampir, in turn derived from Serbo-Croatian vampir, continuing Proto-Slavic *ǫpyrь,[12][13] although Polish scholar K. Stachowski has argued that the origin of the word is early Slavic *vąpěrь, going back to Turkic oobyr.[14] Several European languages, including English, have borrowed the word polje (meaning "large, flat plain") directly from the former Yugoslav languages (i.e. Slovene, Croatian, and Serbian). During the heyday of the USSR in the 20th century, many more Russian words became known worldwide: da, Soviet, sputnik, perestroika, glasnost, kolkhoz, etc. Another borrowing from Russian is samovar (lit. "self-boiling").

Inside the Slavic area

Borrowings from one Slavic language to another are also noted within Slavic languages, for example, medieval polonisms and russicisms in the literary Ukrainian and Belarusian languages.

Following the baptism of Poland the Polish language was influenced by Czech brought by missionaries from the Kingdom of Bohemia.[15]

Czech "wakers" (Czech: buditelé, "evocative") and Slovenian linguists of the late 19th century also turned to the Russian language in order to reslavicize their resurgent languages and clear them of foreign language borrowings. This was mainly due to the imposition of the German language on Slavic-speaking areas, and gave significant results (for example, the word vozduh ("air"), translated into Czech and Slovenian).

See also

- Russianism — borrowing from the Russian language.

- Church Slavicism — a word or phrase borrowed from the Church Slavonic language.

- Bohemism — from the Czech language.

- Polonism — from the Polish language.

- Ukrainism — from the Ukrainian language.

References

- ↑ Hellquist, Elof (1922). "torg". Svensk etymologisk ordbok (in Swedish) – via Project Runeberg.

- ↑ Hellquist, Elof (1922). "humle". Svensk etymologisk ordbok (in Swedish) – via Project Runeberg.

- ↑ Hellquist, Elof (1922). "räka". Svensk etymologisk ordbok (in Swedish) – via Project Runeberg.

- ↑ Hellquist, Elof (1922). "tolk". Svensk etymologisk ordbok (in Swedish) – via Project Runeberg.

- ↑ Hellquist, Elof (1922). "pråm". Svensk etymologisk ordbok (in Swedish) – via Project Runeberg.

- ↑ On the Earliest Slavonic Loanwords in Finnic. Ed. by Juhani Nuorluoto, Helsinki 2006, ISBN 9521028521

- ↑ THE FINNISH-RUSSIAN RELATIONSHIPS: THE INTERPLAY OF ECONOMICS, HISTORY, PSYCHOLOGY AND LANGUAGE Mustajoki Arto, Protassova Ekaterina, 2014

- ↑ Titz, Karel (1922). "Naše řeč – Ohlasy husitského válečnictví v Evropě". Československý Vědecký ústav Vojenský (in Czech): 88. Retrieved 26 January 2019.

- ↑ Harper, Douglas. "vodka". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 18 May 2007.

- ↑ Merriam-Webster's Online Dictionary. Retrieved 28 April 2008

- ↑ Harper, Douglas. "sable". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 18 May 2007.

- ↑ cf.: Deutsches Wörterbuch von Jacob Grimm und Wilhelm Grimm. 16 Bde. [in 32 Teilbänden. Leipzig: S. Hirzel 1854–1960.], s.v. Vampir; Trésor de la Langue Française informatisé; Dauzat, Albert, 1938. Dictionnaire étymologique. Librairie Larousse; Wolfgang Pfeifer, Етymologisches Woerterbuch, 2006, p. 1494; Petar Skok, Etimologijski rjecnk hrvatskoga ili srpskoga jezika, 1971–1974, s.v. Vampir; Tokarev, S.A. et al. 1982. Mify narodov mira. ("Myths of the peoples of the world". A Russian encyclopedia of mythology); Russian Etymological Dictionary by Max Vasmer.

- ↑ Harper, Douglas. "vampire". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 21 September 2007.

- ↑ Stachowski, Kamil. 2005. Wampir na rozdrożach. Etymologia wyrazu upiór – wampir w językach słowiańskich. W: Rocznik Slawistyczny, t. LV, str. 73–92

- ↑ Kuraszkiewicz, Władysław (1972). Gramatyka historyczna języka polskiego (in Polish). Warszawa: Państwowe Zakłady Wydawnictw Szkolnych.

External links

Bibliography

- L. I. Timofeev, S. V. Turaev (1974). Slavicism // Dictionary of literary terms (in Russian). Moscow: «Просвещение».

- A. P. Kvyatkovsky (1966). Slavicisms. Soviet encyclopedia (in Russian). Moscow.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Ulyanov I. S. (2004). Slavicisms in the Russian language (verbs with non-consonantal prefixes) (in Russian). Moscow: Управление технологиями. ISBN 5-902785-01-4.