| Siege of Motya (398 BC) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Second Sicilian War | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

Syracuse Sicilian Greeks | Carthage | ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

Dionysius I Leptines | Himilco | ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| 80,000 infantry, 3,000 cavalry, 200 ships, 500 transports | 100,000, 100 triremes | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| Unknown | Unknown | ||||||||

The siege of Motya took place in summer 398 BC in western Sicily. Dionysius, after securing peace with Carthage in 405 BC, had steadily increased his military power and had tightened his grip on Syracuse. He had fortified Syracuse against sieges and had created a large army of mercenaries and a large fleet, in addition to employing the catapult and quinqueremes for the first time in history. In 398 BC, he attacked and sacked the Phoenician city of Motya despite the Carthaginian relief effort led by Himilco. Carthage also lost most of her territorial gains secured in 405 BC after Dionysius declared war on Carthage in 398 BC.

Background

Carthage had stayed away from Sicilian affairs for 70 years after the defeat at Himera in 480 BC. However, Carthage, responding to the appeal for aid of Segesta against Selinus, had sent an expedition to Sicily, resulting in the sacking of Selinus and Himera in 409 BC under the leadership of Hannibal Mago.[1] Responding to Greek raids on her Sicilian domain,[2] Carthage launched an expedition that captured Akragas in 406 BC and Gela and Camarina in 405 BC.[3] The conflict ended in 405 BC when Himilco and Dionysius, leader of the Carthaginian forces and tyrant of Syracuse respectively, concluded a peace treaty.

Peace of 405 BC

Exactly why Himilco agreed to peace is unknown; it is speculated that a plague outbreak in the Punic army may have been the reason. Dionysius, as future events would indicate, merely chose peace as an opportunity to gather strength and renew the war later.

The treaty secured the Carthaginian sphere of influence in western Sicily, and made the Elymians and Sicani part of Carthaginian sphere of influence. The Greek cities of Selinus, Akragas, Gela and Camarina (Greeks were allowed to return to these cities) became tributary to Carthage. Both Syracuse and Carthage pledged to respect the independence of the Sicels, Leontini and the city of Messana.[4]

A tyrant triumphs

Dionysius, who had obtained his power by condemning and executing his fellow Greek generals, faced discontent among the Greeks after he had evacuated both Gela and Camarina after the Battle of Gela in 405 BC. Some Syracusans tried to stage a coup in 405 BC, but Dionysius had managed to defeat the rebels through speedy action and enemy bungling.[5] After the treaty with Carthage was signed, Syracuse was hemmed in by the territories of Camarina and Leontini, the former a vassal of Carthage and the latter hostile to Syracuse, while the Syracusan rebels settled in the city of Aetna.[6]

Between 405 BC and 397 BC, Dionysius increased the might of Syracuse, dealt with attempts to overthrow him, and made Syracuse the best defended city in the whole Greek world. His activities, briefly, were as follows:

- Enhancing Syracusan defenses: Dionysius populated the island of Orytiga (where the old city of Syracuse stood) with loyal mercenaries and close supporters, and built a wall on the isthmus connecting it with the mainland. Two new forts were built, one on the isthmus and one on the far end of the Epipolae Plateau at Euryalos.[7] He incorporated the walls built during the Athenian Expedition into the city for settling the people in Achradina. Finally in 402 BC, Dionysius started building a wall that would enclose the whole Epipolae Plateau, which was completed by 399 BC.[8] Employing tens of thousands of workers working on different sections of the wall, with Dionysius working alongside and offering prizes to the best workers, the wall was speedily completed.[9] Syracuse became the best fortified city of the Greek world, and Dionysius ensured his own security by building a fortress manned by loyal supporters within the city walls.

- Enhancing combat effectiveness: Dionysius continuously increased the size of his army by hiring mercenaries and building new ships. Greek citizen soldiers normally supplied their own arms and armor, but Dionysius hired workmen from Italy, Greece and Africa to supply his soldiers with arms. Over 140,000 sets of arms, helmets and mails were made. By supplying soldiers with standard issue arms and opening recruitment to all social classes, Dionysius managed to increase the size of his army (prior to this, only mercenaries and citizens able to supply their own arms were the backbone of the army). These workmen also constructed catapults and quinqueremes, giving him a battlefield advantage for a while.[10] Dionysius also built 200 new warships, refitted 110 old ones, and also commissioned 160 transports. A secret harbour was created at Laccium covered with screens, which could house 60 triremes.[11]

- Expanding Syracuse's domain: Dionysius broke the peace treaty in 404 BC by attacking the Sicel city of Herbessus.[12] Carthage did nothing, but part of the Syracusan army joined the Syracusan rebels from Aetna, and with help from Messina and Rhegion, managed to besiege Dionysius in Syracuse. Dionysius thought about fleeing the beleaguered city, and only the bungling of the rebels and the help of some Italian mercenaries saved the day for him.[13] Between 403 and 398 BC, Dionysius destroyed the Ionian Greek cities of Catana, which was given to the Campanians, and Naxos, whose Greek citizens he sold into slavery, and gave the city to the Sicels. Lastly, he conquered Leontini, which surrendered without resistance. Dionysius also strengthened his ties with the Italian Greeks by marrying Doris of Locris.[14] His overtures of friendship with Rhegion fell on deaf ears, however. Carthage did nothing to stop these violations of the peace treaty, namely the attacks on the Sicels and the conquest of Leontini.

In 398 BC, Dionysius sent an embassy to Carthage to declare war unless they agreed to give up all the Greek cities under their control. Before the embassy returned from Carthage, Dionysius let loose his mercenaries on Carthaginians living in Syracusan lands, putting them to the sword and plundering their property. Then he set out for Motya with his army, accompanied by 200 warships and 500 transports carrying supplies and war machines.[15]

Siege of Motya: initial steps

As Dionysius and his army marched west along the southern coast of Sicily, Greek cities under Carthaginian control rebelled, killed Carthaginians living in their cities, looted their property, and sent soldiers to join Dionysius. Sicels, Sikans, and the city of Messene also sent contingents, so by the time Dionysius reached Motya, his army had swelled to 80,000 infantry and 3,000 cavalry.[16] Dionysius sent his navy under his brother Leptines to blockade Motya,[17] and himself moved with the army to Eryx, which surrendered to him. Even the city of Threame declared for him, leaving only the cities of Panormus, Solus, Ancyrae, Segesta, and Entella loyal to Carthage in Sicily. Dionysius raided the surrounding areas near the first three, then placed Segesta and Entella under siege. After these cities had repulsed several assaults, Dionysius himself returned to Motya to oversee the progress of the siege.[18] It was assumed that the cities would surrender once Motya was captured.[19]

Fortifications at Motya

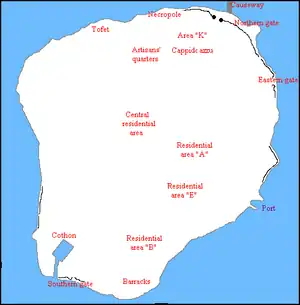

The Phoenician city of Motya was situated on a small island in the middle of a mostly shallow lagoon. It was surrounded by a wall which included at least 20 watch towers, and the walls often rose from the water's edge to a height 8 to 9 metres (26 to 30 ft) and thickness of 6 metres (20 ft). Lack of space had compelled the citizens to construct houses often six floors high, which often towered over the walls. It seemed that Motya had no standing navy,[20] and may have had a Carthaginian garrison stationed in the city. The island was connected to the mainland by a mole 1,500 metres (4,900 ft) long and 10 metres (33 ft) wide on the northern side of the island, with a gate flanked by two towers on the island end. A mixed population of Phoenicians and Greeks lived inside the city. The citizens cut up the mole and prepared for a siege before the Greeks arrived to start the blockade.[21]

Carthage comes calling

Little is known of the activities of Carthage during 405–397 BC except that a plague had swept through Africa, which had been carried by the returning army in 405 BC, weakening Carthage. Himilco was again given the task of responding to the threat. While raising a mercenary army (Carthage did not maintain a standing army) Himilco sent ten triremes to raid Syracuse itself. The raiders entered the Great Harbour of Syracuse and destroyed all the ships they could find. Lacking an army, Himilco was unable to pull off a feat similar to the one Scipio African accomplished at Carthago Nova in 209 BC: attack an almost undefended city while the main army was away and capture it.[22]

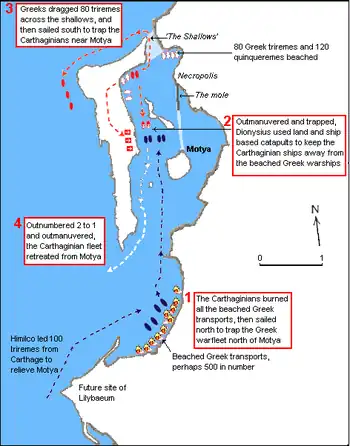

Himilco next manned 100 triremes with picked crews and sailed to Selinus in Sicily, arriving at night. From there, the Punic navy sailed to Motya the following day and fell on the transports beached near Lilybaeum, destroying all that lay at anchor. Then the Carthaginian fleet moved into the area between Motya and the peninsula to the west of the lagoon, trapping the beached Greek fleet on the northern shallows of the lagoon.[18]

Trappers trapped

In 405 BC, the Spartan navy under Lysander had managed to capture the majority of the Athenian navy in the Battle of Aegospotami while it lay at anchor. It is unknown why Himilco chose to go after the transports instead of attacking the beached Greek warships to the north of Motya. The loss of the war fleet would have forced Dionysius to lift the siege, giving Himilco a chance to carry the war to Syracuse.[23]

Himilco, however, had managed to put the Syracusan navy in a similar position the Persians were in at the Battle of Salamis: while the Carthaginian ships had room to maneuver, the Greeks did not, which nullified the numerical superiority and heavier Greek ships (the Greeks had quinqueremes, the Carthaginians did not). Had Dionysius sent ships south to meet the Carthaginians, the depth of the lagoon would mean a small number of his ships would have emerged to the south of Motya to face the entire Carthaginian fleet. Himilco would then have the advantage of numbers and room to maneuver and could destroy the Greek ships in detail.

Dionysius in response launched his ships with a great number of archers and slingers and supported them with his land-based catapults. While these dueled with the archers and slingers on board the Carthaginian triremes, taking a heavy toll and preventing Himilco from reaching the beached ships, Dionysius hatched a scheme. He had his men construct a road of wooden planks on the northern isthmus, on which 80 triremes were then hauled to the open sea to the north of the isthmus. Once properly manned, these ships sailed south along the peninsula. The Carthaginian fleet now facing encirclement, Himilco chose not to fight a two-front battle against superior numbers, and sailed away to Carthage.[24] He had accomplished little except making a sizable dent in Syracusan shipping.

Assault on Motya

Without interference from the Carthaginian fleet, work on the mole progressed smoothly. As Motya herself lacked ships, they could do little until the mole came within range of arrows from their walls. Once the mole was completed, Dionysius set forward his siege towers, which were taller than the walls of Motya and equaled the height of the tallest buildings in the city. A storm of arrows and projectiles from archers and catapults cleared the wall of defenders. Then battering rams were employed against the gates.

The Phoenicians countered by putting men on ship masts and protecting them with breastworks built on the walls. These "crows' nests" were then put beyond the walls, and from these, flax, covered in burning pitch, was dropped on the siege engines, burning them. However, the Greeks learned to douse the flames with firefighting teams, and the engines finally reached the walls despite Carthaginian efforts.[25]

Urban warfare

Forcing holes in the wall itself was only the first step in reducing the city. As the Greek troops advanced, the Phoenicians launched a storm of projectiles (arrows, stones) from the rooftops and houses and took a heavy toll on the attackers. The Greeks next pushed the siege towers next to the houses closest to the walls and sent troops on the roofs using gangways, who forced their way into the houses. A fierce hand-to-hand struggle began, the desperate resistance of the Phoenicians (who expected no mercy from the Greeks) taking a heavy toll on the attackers.

For several days, the grim contest continued within the beleaguered city from dawn to dusk. Unable to gain anything in this slugging contest, Dionysius decided to change tactics. The battle usually started at daybreak and continued until nightfall, when the Greeks withdrew to rest. One day, Dionysius sent a picked group of mercenaries under a Thurian named Archylus at night with ladders to secure vantage points. Under cover of darkness, this commando detachment managed to take hold of the positions before the Phoenicians discovered what was going on.[26] Thus the Greeks gained the advantage, and now the weight of numbers was enough to overcome all resistance. Dionysius had intended to secure as many prisoners as possible for the slave market, but the Greeks vented their frustrations by indiscriminate killing of the population. Dionysius could only save those who sought refuge in the temples.

Aftermath

Dionysius crucified all the Greeks who had fought on the side of Carthage. It is not known if these were mercenaries employed by Carthage or citizens of Motya. Dionysius sacked the city and divided the vast spoils among his troops. He garrisoned the ruins with an army made mostly of Sicels under an officer named Biton, and then marched away to continue the siege of Segesta and Entella. It is not known what he did there, but the cities continued to resist. The majority of the fleet sailed back to Syracuse, while Leptines remained behind with 120 ships at Eryx.

Motya as a city was never rebuilt. Himilco chose to resettle the survivors at Lilybaeum, which would become the main base of Carthage in future. That city would never fall to siege or assault by Greeks or Romans while in Carthaginian possession. Carthage, however, sent an army and fleet to Sicily under Himilco, who had been elected "king" in 397 BC. Himilco chose to sail to Panormus, from where the attack on Syracuse and her allies would take place, which would culminate in the siege of Syracuse.

In fiction

The siege is a major event in the 1965 historical novel The Arrows of Hercules by L. Sprague de Camp.

Bibliography

- Baker, G. P. (1999). Hannibal. Cooper Square Press. ISBN 0-8154-1005-0.

- Warry, John (1993). Warfare in The Classical World. Salamander Books Ltd. ISBN 1-56619-463-6.

- Lancel, Serge (1997). Carthage A History. Blackwell Publishers. ISBN 1-57718-103-4.

- Bath, Tony (1992). Hannibal's Campaigns. Barns & Noble. ISBN 0-88029-817-0.

- Kern, Paul B. (1999). Ancient Siege Warfare. Indiana University Publishers. ISBN 0-253-33546-9.

- Freeman, Edward A. (1892). Sicily Phoenician, Greek & Roman (Third ed.). T. Fisher Unwin.

- Church, Alfred J. (1886). Carthage (4th ed.). T. Fisher Unwin.

- Whitaker Joseph I.S. (1921). Motya, A Phoenician Colony in Sicily. G. Bell & Sons.

References

- ↑ Kern, Paul B., Ancient Siege Warfare, pp. 163–168

- ↑ Freeman, Edward A., Sicily, pp. 144–147

- ↑ Kern, Paul B., Ancient Siege Warfare, pp. 168–172

- ↑ Church, Alfred J., Carthage, pp. 44–45

- ↑ Kern, Paul B., Ancient Siege Warfare, p. 174

- ↑ Freeman, Edward A., Sicily, pp. 153–154

- ↑ Freeman, Edward A., Sicily, p. 158

- ↑ Diod., 15.13.5

- ↑ Kern, Paul B., Ancient Siege Warfare, pp. 174–175

- ↑ Kern, Paul B., Ancient Siege Warfare, p. 177

- ↑ Diod., 14.7.2-3

- ↑ Freeman, Edward A., Sicily, p. 157

- ↑ Freeman, Edward A., Sicily, pp. 158–159

- ↑ Freeman, Edward A., Sicily, pp. 160–163

- ↑ Kern, Paul B., Ancient Siege Warfare, p. 178

- ↑ Whitaker Joseph I.S., Motya, pp. 75–76

- ↑ Diod., 14.48.4

- 1 2 Whitaker, Joseph I.S., Motya, p. 78

- ↑ Diodurus Siculus, XIV.49

- ↑ Whitaker, Joseph I.S., Motya, p. 77

- ↑ Kern, Paul B., Ancient Siege Warfare, p. 180

- ↑ Whitaker, Joseph I.S., Motya, p. 78 note-2

- ↑ Diodurus Siculus, XIV.50

- ↑ Whitaker, Joseph I.S., Motya, p80-84

- ↑ Kern, Paul B., Ancient Siege Warfare, pp. 181–182

- ↑ Kern Paul B., Ancient Siege Warfare, p. 183

External links

- Diodorus Siculus translated by G. Booth (1814) Complete book (scanned by Google)

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Smith, William, ed. (1870). Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Smith, William, ed. (1870). Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology. {{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)