Shubuta, Mississippi | |

|---|---|

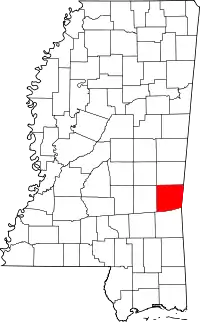

Location of Shubuta, Mississippi | |

Shubuta, Mississippi Location in the United States | |

| Coordinates: 31°51′39″N 88°42′2″W / 31.86083°N 88.70056°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Mississippi |

| County | Clarke |

| Area | |

| • Total | 2.41 sq mi (6.25 km2) |

| • Land | 2.41 sq mi (6.25 km2) |

| • Water | 0.00 sq mi (0.00 km2) |

| Elevation | 203 ft (62 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

| • Total | 406 |

| • Density | 168.26/sq mi (64.97/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-6 (Central (CST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-5 (CDT) |

| ZIP code | 39360 |

| Area code | 601 |

| FIPS code | 28-67520 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0677756 |

Shubuta is a town in Clarke County, Mississippi, United States, which is located on the eastern border of the state. The population was 441 as of the 2010 census,[2] down from 651 at the 2000 census. Developed around an early 19th-century trading post on the Chickasawhay River, it was built near a Choctaw town. Shubuta is a Choctaw word meaning "smokey water".[3]

East of the town is a bridge over the river; it is known as the "Hanging Bridge". It was the site of the 20th-century lynch murders of four young blacks in 1918, two of whom were pregnant women, and two male youths in 1942. National newspapers covered the lynchings, and the NAACP conducted investigations in both cases. No one was prosecuted for the murders. In addition to recognition of historic houses in town, the Shubuta Bridge is listed on the National Register of Historic Places for its significance in state and national history. A total of 10 blacks were lynched in Clarke County from 1877 to 1950.

History

.jpg.webp)

Located along the Chickasawhay River, the small town of Shubuta was incorporated in 1865. It had started in the 1830s as a trading post community, located near the Choctaw village of Yowani. During the period of Indian Removal, under the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek, the Choctaw people ceded most of their lands to the United States. Under the Indian Removal Act, they were given land in exchange in Indian Territory (now Oklahoma), and most of the people were forced to relocate west of the Mississippi River. Their traditional homelands in the Southeast were sold or made available by lotteries to European Americans for settlement.

The first record of the word "Shubuta" appears on Bernard Roman's "Map of 1772", a copy of which appears in Riley's History of Mississippi. The name was spelled as "Chobuta", which means "smoky water" in the Choctaw language. It became a market town for an area developed for cotton plantations, which depended on the labor of enslaved African Americans. Cotton was shipped downriver from Shubata to Mobile, Alabama, and then to other major ports. The town started growing more rapidly in the 1850s after being connected to other communities by the railroad. At one time the largest town between Meridian, Mississippi, and Mobile, Shubuta attracted people from 40 miles (64 km) around to shop at its many mercantile businesses.

The first newspaper in the area was the Mississippi Messenger, established in 1879 by Judge Charles A. Stovall. Six houses within Shubuta are listed on the National Register of Historic Places. These are listed in National Register of Historic Places listings in Clarke County, Mississippi, which provides a map link locating them all.

20th-century lynchings

The county had 10 documented lynchings in the period from 1877 to 1950; most took place in the 20th century.[4]

1918 lynchings

In late December 1918, five weeks after the armistice was signed in the Great War, four black farmworkers were lynched and hanged from a railroad bridge in Shubuta. They were brothers, Major (age 20) and Andrew (age 16) Clark, along with two black sisters, Alma (age 16) and Maggie House (age 20) (their surname was sometimes spelled as "Howze"), allegedly for the murder of Dr. H. L. Johnston, a married white dentist who was living at his father's farm, where the four younger people all worked. Both sisters were pregnant: Maggie was six months pregnant and Alma was due in two weeks.[5] When the NAACP asked for a state investigation, their representative was told by Mississippi Governor Theodore Bilbo to "go to hell".[6]

The NAACP contracted with Robert Church, a white detective from Memphis, Tennessee, to investigate the four lynchings. He learned that Johnston was fatally shot while milking on December 10, 1918. Major Clark had found him and carried him into the house. Johnston was said to have sexually assaulted and impregnated each of the House sisters.[7] After the Clark brothers started working on the farm, Major Clark and Maggie House developed a romantic relationship. Johnston the son had jealously threatened Clark, saying he would kill the young black man unless he ended his relationship with House. Johnston apparently had affairs with white women, too, and his father believed he had been shot by a white man,[7] as did others in town.[5]

The lynching was documented as premeditated and coordinated, as many such events were. It was a year of white on black violence: in 1918 there had been 62 lynchings in the United States since January 1, seven of them in Mississippi.[8] Deputy County Sheriff Crane colluded with the mob to provide access to the victims at the jail, claiming that he had been overpowered by the mob. In addition, men cut off power to the town from the main station, perhaps to support witnesses' later claims of being unable to identify members of the mob.[7]

The four young people were brutally treated. Maggie was smashed in the face with a wrench. All four were thrown from the bridge, but Maggie caught on to the bridge and survived the initial attempt on her life.[5] When she was thrown from the bridge a second time, she again grabbed a railing. The mob hauled her up a third time, and were finally successful in throwing her over and hanging her. When the victims were buried the next day, witnesses reported seeing Alma House's unborn baby moving in the womb.[9]

1942 lynchings

In 1942 during World War II, Ernest Green, a fourteen-year-old black boy, along with Charlie Lang, aged fifteen, were seen speaking to Dorothy Martin, a thirteen-year-old white girl whom they knew from the area. Accounts vary as to what took place. One or more whites who saw the three youths together while driving by reported the incident to Martin's father. Another account said that the incident was "attempted rape" after Dorothy told her parents about it. The boys were arrested by Clarke County Sheriff Lloyd McNeal, and appeared before justice of the peace W.E. Eddins, perhaps in a hearing at his residence, where they allegedly confessed to attempted rape. By October 10 the boys were held in the jail at the county seat of Quitman. On October 12, Quitman Town Marshall G.F. Dabbs handed the boys over to several white men, who took the boys away.[6]

The men took the boys to the Shubuta railroad bridge, where they mutilated them by cutting off their genitals, and hanged the youths from the bridge.[6] The sheriff told the Pittsburgh Courier that the local people respected law and order, but that "Them niggers is gettin’ uppity, you know.”[10] Walter Atkins, a black journalist, asserted in 1942 that the “rickety old span is a symbol of the South as much as magnolia blossoms or mint julep colonels.”[11] Sherriff McNeal was said to have expressed remorse on his deathbed for the murders of Green and Lang.[6] Governor Paul Johnson declared that the lynchings were murders, there was nothing he could do about it, and criticized first lady Eleanor Roosevelt for discussing the matter in the national media.[12]

Because of its own history and connection to the white lynchings of thousands of blacks in the South, the bridge was added to the National List of Historic Places in 1988.[13] As of 2016, the abandoned bridge still stands at the end of East Street but is blocked off from access by a barricade.[11][14]

Voter suppression and Great Migration

At the end of the 19th and early 20th centuries, Mississippi disenfranchised most black voters through passing a new constitution that raised barriers to voter registration. In Shubuta whites had also suppressed black voting by destroying ballots, imposing poll tests such as correctly guessing the number of jellybeans in a jar, and intimidation by the Ku Klux Klan.[11] Following the 1918 lynchings, many black workers left Clarke County, leaving cotton to rot in the fields. The town's population dropped by 21% (See table below) and the county population dropped 17% from 1910 to 1920. (See Demographics, Clarke County, Mississippi)

The first wave of the Great Migration from the rural South continued to the Second World War. In the 1930s, a number of African-American residents from the Shubata area followed Reverend Louis W. Parson to Albany, New York to escape the violence and in a search for industrial jobs and better opportunities.[11] They created a community to the west of the city, building houses along Rapp Road within what was one land parcel purchased by Parson. Now known as the Rapp Road Community Historic District, the area is listed on the NRHP.

Geography

Shubuta is located near the southern border of Clarke County at 31°51′39″N 88°42′2″W / 31.86083°N 88.70056°W (31.860939, -88.700690),[15] on the west side of the Chickasawhay River. U.S. Route 45 bypasses the town on the west, leading north 13 miles (21 km) to Quitman, the county seat, and south 14 miles (23 km) to Waynesboro. Mississippi Highway 145, which leads through the center of Shubuta, follows the old alignment of US 45.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the town has a total area of 1,500 acres (6.2 km2), all land.[2]

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1880 | 754 | — | |

| 1890 | 589 | −21.9% | |

| 1900 | 451 | −23.4% | |

| 1910 | 1,168 | 159.0% | |

| 1920 | 912 | −21.9% | |

| 1930 | 720 | −21.1% | |

| 1940 | 756 | 5.0% | |

| 1950 | 782 | 3.4% | |

| 1960 | 718 | −8.2% | |

| 1970 | 602 | −16.2% | |

| 1980 | 626 | 4.0% | |

| 1990 | 577 | −7.8% | |

| 2000 | 651 | 12.8% | |

| 2010 | 441 | −32.3% | |

| 2020 | 406 | −7.9% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[16] | |||

2020 census

| Race | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| White (NH) | 62 | 15.27% |

| Black or African American (NH) | 338 | 83.25% |

| Mixed/Multi-Racial (NH) | 2 | 0.49% |

| Hispanic or Latino | 4 | 0.99% |

| Total | 406 |

As of the 2020 United States census, there were 406 people, 144 households, and 101 families residing in the town.

2000 census

As of the census[20] of 2000, there were 651 people, 244 households, and 165 families residing in the town. The population density was 271.0 inhabitants per square mile (104.6/km2). There were 270 housing units at an average density of 112.4 per square mile (43.4/km2). The racial makeup of the town was 25.50% White, 73.89% African American, 0.15% from other races, and 0.46% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 1.38% of the population.

There were 244 households, out of which 38.1% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 40.2% were married couples living together, 23.8% had a female householder with no husband present, and 32.0% were non-families. 28.7% of all households were made up of individuals, and 16.0% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.67 and the average family size was 3.35.

In the town, the population was spread out, with 32.3% under the age of 18, 9.8% from 18 to 24, 26.1% from 25 to 44, 19.7% from 45 to 64, and 12.1% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 33 years. For every 100 females, there were 83.4 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 75.7 males.

The median income for a household in the town was $18,438, and the median income for a family was $21,719. Males had a median income of $24,688 versus $17,813 for females. The per capita income for the town was $9,094. About 38.5% of families and 44.8% of the population were below the poverty line, including 59.4% of those under age 18 and 35.9% of those age 65 or over.

Industry

Shubuta was the second home of Hanson Scale Company, a bathroom scale manufacturer. It was later owned by the Sunbeam Corporation. Shubuta is the home of Mississippi Laminators. Producing laminated beams, the company has been in business here since the early 1970s.

Education

Shubuta is served by the Quitman School District.

Notable people

- Robert Staten, former NFL running back[21]

- Annibel Jenkins, Georgia Tech professor

- Tarvarius Moore, NFL Strong Safety

References

- ↑ "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 24, 2022.

- 1 2 "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (G001): Shubuta town, Mississippi". U.S. Census Bureau, American Factfinder. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved October 6, 2014.

- ↑ Primm, Rosalie (August 6, 1981). "Shubuta Clarke County's first Indian Tourist Center". Clarke County Tribune. Retrieved December 18, 2019 – via newspapers.com.

- ↑ Lynching in America, 2nd edition Archived 2018-06-27 at the Wayback Machine, Supplement by County, p. 4

- 1 2 3 "TOO NAUSEATING TO PUBLISH" (PDF). Cayton's Weekly (Seattle, Washington), reprinted from the May Crisis. May 24, 1919. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 18, 2017. Retrieved December 26, 2017., Chronicling America, Library of Congress

- 1 2 3 4 "Ernest Green and Charles Lang". Nuweb9, Northeastern University School of Law. Retrieved December 27, 2017.

- 1 2 3 "Maggie and Alma House, Major and Andrew Clarke". State Sanctioned website. August 6, 2015. Retrieved December 26, 2017.

- ↑ "Lynching an American Pastime", Washington Bee, 04 January 1919; posted at State Sanctioned website; accessed 8 March 2018

- ↑ "Shubuta, Mississippi". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. December 28, 2016. Retrieved December 26, 2017.

- ↑ Mitchell, Jerry (May 1, 2016). ""Hanging Bridge" signing May 2 at Lemuria". Clarion Ledger. Retrieved December 26, 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 Jennifer A. Lemak, Southern Life, Northern City, The History of Albany's Rapp Road Community, Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 2008

- ↑ Bernstein, Victor (November 7, 1942). "Lack Power For Decisive Action". Pittsburgh Courier and PM. ProQuest 202120365.

- ↑ "NATIONAL REGISTER DIGITAL ASSETS". Retrieved December 26, 2017.

- ↑ Ward, Jason Morgan (May 3, 2016). "The Infamous Lynching Site That Still Stands in Mississippi". Time. Retrieved December 26, 2017.

- ↑ "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. February 12, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- ↑ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ↑ "Explore Census Data". data.census.gov. Retrieved May 21, 2022.

- ↑ https://www.census.gov/

- ↑ "About the Hispanic Population and its Origin". www.census.gov. Retrieved May 18, 2022.

- ↑ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ↑ "Robert Staten". ProFootballArchives.com. Retrieved May 17, 2020.

Further reading

- Terrence Finnegan, A Deed So Accursed: Lynching in Mississippi and South Carolina, 1881 – 1940, Charlottesville, Virginia: University of Virginia Press, 2013

- NAACP, Thirty Years of Lynching in the United States, 1898 – 1918, National Association of Colored People, 1919

- NAACP papers, Part 7, Series A, Reels 1 and 2, University of Michigan microfilm collections

- Jason Morgan Ward, "The Infamous Lynching Site That Still Stands in Mississippi", adapted from Hanging Bridge: Racial Violence and America’s Civil Rights Century, 2016, excerpt printed in TIME Magazine, 3 May 2016

- Jason Morgan Ward, Hanging Bridge: Racial Violence and America’s Civil Rights Century, University of Oxford Press, 2016

- Gayle Graham Yates, Life and Death in a Small Southern Town: Memories of Shubuta, Mississippi, Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press, 2004