42°20′N 19°38′E / 42.333°N 19.633°E

| Part of a series on |

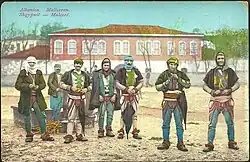

| Albanian tribes |

|---|

|

Shkreli is a historical Albanian tribe and region in the Malësia Madhe region of northern Albania and is majority Catholic. With the expansion of the Ottoman Empire, part of the tribe migrated to Rugova in Western Kosovo beginning around 1700, after which they continued to migrate into the Lower Pešter and Sandžak regions (today in Serbia and Montenegro).

The Shkreli tribe that migrated to Kosovo converted to Islam in the 18th century and maintained the Albanian language as their mother tongue.

Some members of the Shkreli within the Pešter region and in Sandžak (known as Škrijelj/Serbian: Шкријељ) converted to Islam and became Slavophones by the 20th century, which as of today they now self-identify as part of the Bosniak ethnicity, although in the Pešter plateau they partly utilized the Albanian language until the middle of the 20th century.[1] The Shkreli in Albania and Montenegro are predominantly Catholic.

The Shkreli tribe's patron saint is St. Nicholas (Shënkoll).

Name

Various theories have been proposed for the etymology of the name Shkreli. It first appears as a patronymic and village name in 1416 in its present location. It has been spelled as Scirelli, Screlli, Strelli, Scrielli (1703) and Scarglieli (1614) in Latin. An older, unproven historically, etymology links it to Saint Charles (Shën Kërli in Albanian), who is hypothesized to have been the patron saint of an old church in the area.[2] In reality, the name of the region was given to it by the kin community, which apart from Shkreli appears throughout northern Albania in the Middle Ages.[3] Another, more linguistically based approach links the name to shkrelë, a word used in Gheg Albanian for big corn leaves. Corn is one of the few crops that are cultivated extensively in the available arable land of the Shkreli. The people of the region are called Shkrelë. Those in the Sandžak region who have been Slavicized use the surname Škrijelj.

Geography

Shkreli is situated in Malësi e Madhe District, north of the city of Shkodra in the protected area of the Shkreli Regional Nature Park in the valley of Prroni i Thatë (Dry Creek). It forms part of the Shkrel municipal unit. To the north it borders Boga, to the south Lohja and to the west Kastrati. To the east of Shkreli are the slopes of the Northern Mountain Range.

Shkreli comprises four villages Vrith, Bzhetë, Zagorë, Dedaj. These four villages also have additional settlements in Grishaj, Vuç-Kurtaj, Sterkuj, Çekëdedaj, Xhaj, Makaj and Ducaj that are linked to them. A small settlement named Shkrel also exists in the Bushat municipal unit. Outside of Albania, people who trace their origin to Shkreli are found in particular in Ulcinj, Sandžak and the nearby Region in western Kosovo. The Montenegro-Kosovo borderlands are marked by many micro-toponyms like Škrijeljska Hajla and Škrijeljska Reka that are linked to Shkreli.

History

Origins

By oral tradition, the first Shkreli to settle in this region of Albania was Lek Shkreli, who had four sons: Vrith, Ded, Buzhet and Zog/Zag, hence the names of the four main villages of Shkrel: Vrith, Dedaj, Bzheta and Zagora.

Vrith was the oldest of the sons, his family grew largest, and its people are Bajraktar of Shkreli. Deda, Leka’s second son, had three sons: Çek Deda, Pap Deda and Vulet Deda. Buzheta, his third son had three sons as well: Preknici, Duci and Prekduci. Leke’s fourth son, Zogu, only had two sons: Andrea and Jusuf/Joseph (this son said to be islamized).

When the Shkreli tribe arrived in this region of Albania they found a population that was already there and this population was admitted into the tribe; they are called “Anas”:

1. Xhaj in Xhaj

2. Vukaj or Vukelaj in Preknicaj

3. Kolajt in Zagorë

4. Baushi or Kapllajt in Dedaj

5. Luizi in Grykën e Lugjeve

6. Tuçajt who live in Leskovac

Oral traditions and fragmentary stories were collected and interpreted by writers who travelled in the region in the 19th century and early 20th century about the origins of Shkreli.

French consul in Shkodra, Hyacinthe Hecquard in his 1858 Histoire et description de la haute Albanie ou Guégarie notes that Shkreli descend from an old Albanian family in the region of Pejë, whose chief was called Kerli (Carl).[4] Sixty years later, Edith Durham who travelled in the region wrote in High Albania (1908) that she recorded a story in Shkreli that they came from an unknown region of Bosnia. In her 1928 book Some tribal origins, laws, and customs of the Balkans she also notes that this even must have happened around 1600.[5] Carleton S. Coon in his 1944 Mountains of Giants: A Racial and Cultural Study of the North Albanian Mountain Ghegs adopted her hypothesis and further added that the people of Shkreli 'took over a valley whose population was killed and church burned. The name of the church was St. Charles (Albanian: Shën Kerli) which became Shkreli.[6]

Baron Nopcsa, a well-known scholar of the Albanian fis system, noted that the mention of an unknown region of Bosnia could well mean an area of the Sanjak of Novi Pazar or adjacent to it.[7] This region until the late 19th century was administratively part of the Eyalet of Bosnia. Indeed, Albanian pastoral communities from the Plav area used to move their herds in Bosnia during the winter months and then move back in the spring and summer months to their natural grazing lands.[8]

In the decades that followed analysis of recorded historical material, linguistics and comparative anthropology have provided more historically-grounded accounts. A particularly important work in this respect was the publication of the cadaster of Shkodër of 1416-7 in 1942 and the subsequent registry of names of the cadaster in 1945 by Fulvio Cordignano. The full document was translated into Albanian in 1977. It is the first known historical document that mentions Shkreli both as a settlement and as a family name in 1416. The village of Shkreli appears in the cadaster of Shkodra as a small settlement of eight households headed by a Vlash Shkreli.[9]

In 1416, Shkreli appears as a tribe in the process of formation as the village name is also the surname of most of its households, an indication of the kin organization of the settlement.[3] The fact that about half of the households who bore the surname Shkreli lived outside of the settlement points to the fact that Shkreli in 1416 was closer to being a bashkësi (tribe based on kinship relations but with no communal territorial control) than a fis (a kin community that is also identified with a given communal territory).

Ottoman

In 1613, the Ottomans launched a campaign against the rebel tribes of Montenegro. In response, the tribes of the Vasojevići, Kuči, Bjelopavlići, Piperi, Kastrati, Kelmendi, Shkreli and Hoti formed a political and military union known as “The Union of the Mountains” or “The Albanian Mountains” . The leaders swore an oath of besa to resist with all their might any upcoming Ottoman expeditions, thereby protecting their self-government and disallowing the establishment of the authority of the Ottoman Spahis in the northern highlands. Their uprising had a liberating character. With the aim of getting rid of the Ottomans from the Albanian territories[10][11]

Scarglieli was mentioned by Mariano Bolizza in 1614, being part of the Sanjak of Scutari. It was Roman Catholic, had 20 houses, and 43 men at arms commanded by Gjon Poruba.[12] In the late Ottoman period, the tribe of Shkreli consisted of 180 Muslim and 320 Catholic households.[13]

In 1901, in a study conducted by Italian Antonio Baldacci, Shkreli has 4500 Catholic and 750 Muslim citizens.

In years 1916–1918 Franz Seiner observed Shkreli had 415 houses, 2680 individuals: 2300 Catholics and 388 Muslims.

During the Ottoman Empire the Shkreli tribe was in constant warfare with the Empire and enjoyed intermittent autonomy from the Porte. Years at war 1614,1621,1645 (which won them autonomy until 1700), 1803-1817,1834-1840, 1871 war with Turks of Shkodra over mistreatment of local Catholic population of city, Albanian revolts in 1910–1911, etc. Shkreli tribe participated in the League of Prizren 1878-1881 represented by Bajraktar Marash Dashi.

During the Albanian revolt of 1911 on 23 June Albanian tribesmen and other revolutionaries gathered in Montenegro and drafted the Greçë Memorandum demanding Albanian sociopolitical and linguistic rights with four of the signatories being from Shkreli.[14] In later negotiations with the Ottomans, an amnesty was granted to the tribesmen with promises by the government to build one to two primary schools in the nahiye of Shkreli and pay the wages of teachers allocated to them.[14]

Before converting to Islam in the 18th century, most of the Kosovo part of tribe professed Catholicism. The descendants of this tribe in Kosovo have also maintained the Albanian language as their mother tongue. A majority of the Shkreli tribe is Catholic, speaks Albanian and they live in Albania (Shkrel-Shkodër-Lezha-Velipoj) and Montenegro (Ulcinj).[15] The Tribes Patron Saint is St. Nicholas and feast day is celebrated on May 9.

Emigration

| Shkreli dispersal and self-identification | ||

|---|---|---|

| Geographical location | Religion | Language |

| Albania | Roman Catholic (majority), Islam (minority) | Albanian |

| Western Kosovo | Islam | Albanian |

| Pešter, Sandžak, Ulcinj and its surrounding villages (Serbia and Montenegro) | Islam (majority) | Bosnian (majority) Albanian (minority) |

During history parts of the tribe emigrated from Albania to different locations: the Montenegro seaside, to Sandžak and to the Rugova highlands (located in northwestern Kosovo near Pejë). Some of the Rugova Shkrelis moved to the territory of Rožaje and Tutin in 1700, after the Great Serb Migration.[16]

They founded the village named Škrijelje as they continued residing in Sandžak, by appropriating the yat vowel from the Slavic languages, the surname deviated from Shkreli to Škrijelj. Later in the century they populated the Lower Pešter region and the city of Novi Pazar. Shkrelis continued to migrate from Rugova to the territory of Pešter until the 19th century.[17]

The vast majority of Shkreli were assimilated by the Slavic population in the Sandžak region. However, in the villages of Boroshtica, Ugëll, Doli and Gradac at the Upper Peshter plateau, they managed to maintain the original Albanian language until today.

Some of the Shkrelis also migrated to Ulqin and its surrounding villages on the coast and along the Buna river. The Shkrelis of Ulqin are all Albanian and Roman Catholic. Here, they all have the surnames Shkreli, Shkrela, Shkrelja, Skrela, and Skrelja. Those from the Ulqin Shkrelis have always and still maintain close relations with Albania’s Shkrelis and have always intermarried despite living on opposite borders and are still part of the same Bajrak. After the Second World War and especially with the beginning of the Yugoslav Wars, they began migrating to Western Europe, the United States, and Australia.

Most of the Shkrelis that are from Albania proper do not carry Shkreli as a surname. It is only the ones that emigrated from the mountains that carry Shkreli as surnames. Today, people bearing the surname Shkreli (or Škrijelj) live in the following locations:

**

- Montenegro: Bar, Petnjica Municipality (also in the village of Dašča Rijeka, Javorovo and Murovac), Bijelo Polje (also in the village of Ćosoviće), Herceg Novi, Nikšić, Podgorica, Rožaje, Tivat and Ulcinj and surrounding villages.

- Kosovo: Gjakova, Mitrovica, Pejë, and Prishtina.

- Serbia: Belgrade, Novi Pazar (also in the villages of Požega and Rajčinoviće), Sjenica (also in the villages of Bioc, Kamešnica, Međugor and Ugao), Temerin and Tutin (also in the villages of Boroštica, Crnoča, Gradac, Ljeskova, Naboje, Šaronje and Škrijelje).

- Bosnia and Herzegovina: Mostar, Sarajevo and Zenica.

- North Macedonia: Skopje (also in the villages of Batinci, Dračevo, Indžikovo, Ljuboš, Ljubin, Kjojlija, Konjare, Petrovec, Ržaničino), Veles (also in the villages of Crkvino and Gradsko), Prilep (also in the villages of Desovo, Lažani and Žitoše) and Tetovo

- Croatia: Sisak, Split and Zagreb

- Slovenia: Ljubljana

- Turkey: Istanbul, Ankara , Izmit, Izmir , Eskişehir and Sakarya (their surnames are changed into Şenyel, Albayrak, Bayrak, Büyükbayrak, Esen (Šemsović), Sancak, Yener and Yenibayrak).

- Russia: Moscow

- Western Europe: Austria, Belgium, Denmark, England, France, Germany, Italy, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Sweden and Switzerland.

- United States: New York City (especially in the Bronx. Westchester county, Putnam county, Brooklyn), Detroit and its surrounding suburbs.

- Australia

Notable people

- Martin Shkreli - an American businessman, former hedge fund manager, and convicted felon of Albanian origin.

- Lesh Shkreli - a Montenegrin-American former soccer forward of Albanian origin.

- Azem Shkreli - an Albanian writer

See also

References

- ↑ Robert Elsie (30 May 2015). The Tribes of Albania: History, Society and Culture. I.B.Tauris. p. 81. ISBN 978-1-78453-401-1.

- ↑ Topalli, Kolec (2004). Dukuritë fonetike të sistemit bashkëtingëllor të gjuhës shqipe. Shkenca. p. 286. ISBN 9789992793886. Retrieved 17 March 2020.

- 1 2 Pulaha, Selami (1975). "Kontribut për studimin e ngulitjes së katuneve dhe krijimin e fiseve në Shqipe ̈rine ̈ e veriut shekujt XV-XVI' [Contribution to the Study of Village Settlements and the Formation of the Tribes of Northern Albania in the 15th century]". Studime Historike. 12: 122. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- ↑ The Tribes of Albania:History, Society and Culture. Robert Elsie. 24 April 2015. p. 183. ISBN 9780857739322.

- ↑ Durham, Edith (1928). Some tribal origins, laws and customs of the Balkans. p. 28. Retrieved 28 January 2020.

- ↑ Carl Coleman Seltzer; Carleton Stevens Coon; Joseph Franklin Ewing (1950). The mountains of giants: a racial and cultural study of the north Albanian mountain Ghegs. The Museum. p. 45. Retrieved 13 May 2013.

- ↑ The Tribes of Albania:History, Society and Culture. Robert Elsie. 24 April 2015. p. 83. ISBN 9780857739322.

- ↑ Ajeti, Idriz (2017). Studime për gjuhën shqipe [Studies on the Albanian language] (PDF). Academy of Sciences of Kosovo. p. 61. Retrieved 26 February 2020.

- ↑ Zamputi, Injac (1977). Regjistri i kadastrēs dhe i koncesioneve pēr rrethin e Shkodrës 1416-1417. Academy of Sciences of Albania. p. 66. Retrieved 29 January 2020.

- ↑ Kola, Azeta (January 2017). "From serenissima's centralization to the selfregulating kanun: The strengthening of blood ties and the rise of great tribes in northern Albania from 15th to 17th century". Acta Histriae. 25 (2): 349-374 [369]. doi:10.19233/AH.2017.18.

- ↑ Mala, Muhamet (2017). "The Balkans in the anti-Ottoman projects of the European Powers during the 17th Century". Studime Historike (1–02): 276.

- ↑ Early Albania: A Reader of Historical Texts, 11th-17th Centuries. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. 2003. pp. 147–. ISBN 978-3-447-04783-8.

- ↑ Gawrych 2006, p. 31.

- 1 2 Gawrych, George (2006). The Crescent and the Eagle: Ottoman rule, Islam and the Albanians, 1874–1913. London: IB Tauris. pp. 186–187. ISBN 9781845112875.

- ↑ Balkanistica. Vol. 13–14. Slavica Publishers. 2000. p. 41.

- ↑ Mušović, Ejup (1985). Tutin i okolina. Serbian Academy of Science and Arts. p. 27.

- ↑ Glasnik Etnografskog instituta. Vol. 20. Naučno delo. 1980. p. 74.