| Self-Portrait Dedicated to Leon Trotsky | |

|---|---|

| Spanish: Autorretrato dedicado a León Trotsky | |

| |

| Artist | Frida Kahlo |

| Year | 1937 |

| Medium | Oil on masonite[1] |

| Movement | |

| Dimensions | 76.2 cm × 60.96 cm (30.0 in × 24.00 in) |

| Location | National Museum of Women in the Arts, Washington, D.C. |

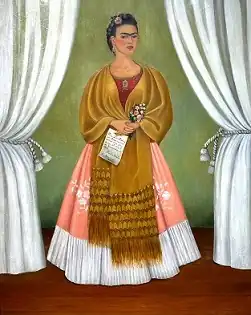

Self-Portrait Dedicated to Leon Trotsky, also known as Between the Curtains, is a 1937 painting by Mexican artist Frida Kahlo, given to Leon Trotsky on his birthday and the 20th anniversary of the October Revolution. Kahlo and her husband, artist Diego Rivera, had convinced government officials to allow Trotsky and his second wife, Natalia Sedova, to live in exile in Mexico. The Russian couple moved into the Blue House (La Casa Azul), where they resided for two years.

Soon after the couples met, Kahlo and Trotsky began showing affection towards each other. A brief affair occurred, but ended by July 1937. A few months later, she presented Trotsky with a self-portrait dedicated to him, which he hung in his study. When Trotsky was assassinated in 1940, Kahlo was heartbroken and planned to destroy the painting. A friend who was visiting at the time, Clare Boothe Luce, convinced her not to do so and acquired the painting herself.

In 1988, Luce donated the painting to Wilhelmina Holladay, co-founder of the National Museum of Women in the Arts in Washington, D.C. Since that time, it has become one of the museum's most popular works. It is also the only Kahlo painting in a Washington, D.C., museum's permanent collection.

Background

Inspiration for the painting

Frida Kahlo (1907–1954) was a Mexican painter whose works, including many self-portraits, made her a symbol of Mexican culture, feminism, and LGBT culture.[2] Many of her surrealist works depict moments in her life, often tragic ones, due to her tumultuous marriage to artist Diego Rivera and her recurring health issues. Around a third of her paintings are self-portraits, which often symbolize her painful experiences. Kahlo's personal life and her artwork were heavily influenced by the Mexicanidad movement, which seeks to revitalize the culture of Mexico's indigenous peoples.[3][4]

On January 9, 1937, Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky and his second wife, Natalia Sedova, arrived in Tampico, Mexico, after living in exile for several years due to Joseph Stalin's success in ousting him from power.[5] Rivera was a Communist who, along with Kahlo, convinced President Lázaro Cárdenas to allow Trotsky into Mexico.[5][6][7] The couple welcomed Trotsky to take up residence in their Blue House (La Casa Azul), located in the Coyoacán neighborhood of Mexico City. Trotsky and Sedova would end up living in the house until April 1939 when Rivera and Trotsky's friendship ended.[5][7]

Kahlo and Rivera's relationship was often fraught. They divorced and then remarried, and each had lovers. Rivera slept with Kahlo's sister for several years and Kahlo had several woman lovers.[4][6] The couple became good friends with Trotsky, although Sedova was not as close since she did not speak English. Trotsky and Kahlo's attraction towards each other occurred shortly after the couples met. He would leave letters to Kahlo inside books she borrowed, and they would meet in a nearby friend's house.[8] Calling Trotsky "The Old Man" (El Viejo), Kahlo was attracted to his resilience in the face of persecution and his revolutionary ideas.[6][9]

By July 1937, their affair ended and Trotsky and Rivera soon reconciled.[5][7] Weeks later, Trotsky wrote to Sedova "She is nothing to me."[8] In October 1937, she gave Trotsky Self-Portrait Dedicated to Leon Trotsky, which was also called Between the Curtains.[5][10] By the following year, thanks in part to André Breton and Jacqueline Lamba's visit to Mexico where they saw Kahlo's work, Kahlo's first major exhibition took place overseas.[5]

Acquistion and display

Wilhelmina Holladay, co-founder along with her husband of the National Museum of Women in the Arts (NMWA) in Washington, D.C., received the painting as a donation from writer and politician Clare Boothe Luce. While visiting Kahlo in Mexico City in 1940, Luce convinced Kahlo not to destroy the painting after she had learned of Trotsky's assassination. Luce was given the painting, and in 1988, gave it to Holladay during a visit to Luce's Watergate apartment.[1][11][12] Since receiving the painting, it has become one of the museum's most famous works.[13] It has been loaned to exhibitions at the Inter-American Development Bank's cultural center, the National Gallery of Australia, and the McMichael Canadian Art Collection. The latter focused on the works of Kahlo, Georgia O'Keeffe, and Emily Carr, representing Mexico, the United States, and Canada, respectively.[14][15]

In 2007, the NMWA presented an exhibition on Kahlo's work. In addition to Self-Portrait Dedicated to Leon Trotsky, there were photographs and private letters available for viewing. Additional activities included learning Mexican dances, viewing the film "The Life and Times of Frida Kahlo", and watching the Maru Montero Dance Company perform.[16] In the early 2020s, the NMWA underwent a $67.5 million renovation.[11] During that time, Self-Portrait Dedicated to Leon Trotsky and ten other paintings were loaned to the National Gallery of Art.[17] The museum reopened in October 2023 with Self-Portrait Dedicated to Leon Trotsky returning as a centerpiece of the NMWA's collection. It is the only Kahlo painting in a Washington, D.C., museum's permanent collection.[11][18]

Description

The oil on masonite painting measures 30 inches tall and 24 inches wide (76.2 cm × 60.96 cm). Kahlo stands poised and confident in the painting. Its setting is inspired by retablos, devotional paintings of religious figures.[3] It depicts Kahlo standing between two white curtains on a stage, holding a letter to Trotsky and a bouquet of flowers.[19] The letter reads "To Leon Trotsky with great affection, I dedicate this painting November 7, 1937. Frida Kahlo. In San Angel. Mexico."(Para Leon Trotsky con todo cariño, dedico esta pintura el dia 7 de Noviembre de 1937. Frida Kahlo. En San Angel. México.)[1][8] The date is not only Trotsky's birthday, but the 20-year anniversary of the October Revolution, November 7, 1917 [O.S. October 25].[8]

Her outfit consists of a dress worn by Zapotec women from the Isthmus of Tehuantepec and was considered to be more subdued compared to other self-portrains. Her top consisted of a huipil, a commonly worn item amongst indigenous women in Mexico and Central America, which is red with green trimming. The huipil also features a bejeweled pendant, though her beige rebozo, similar to a shawl that symbolizes womanhood, covering most of the top. White trimming and white flowers also embroider her coral pink enaguas (petticoat). Kahlo's hairstyle resembles that of women from the Tehuantepec region, being braided and adorned with a pink flower and red ribbon. She is wearing gold earrings and makeup, including bright red lipstick and pink rouge, as well as red fingernail polish. She also has one ring on her right hand.[19]

Analysis

According to Josefina De La Torre from the Fashion Institute of Technology, "her ensemble blends late-30s beauty trends with traditional clothing."[19] Hank Burchard writing in The Washington Post described Kahlo's expression as "solemn bordering on baleful", but also "hard and respectful." Burchard interpreted the painting as a way of Kahlo showing her survival instinct in an art world dominated by men, including her own husband.[14] Sarah Milroy from The Globe and Mail wrote that the painting demonstrates Kahlo's satisfaction with the affair she had with Trotsky, but noting the overall tone is tame compared to her other works.[15]

In 1938, Breton wrote about how deeply moved he was by the painting:[5]

"I have for long admired the self-portrait by Frida Kahlo de Rivera that hangs on a wall of Trotsky's study. She has painted herself dressed in a robe of wings gilded with butterflies, and it is exactly in this guise that she draws aside the mental curtain. We are privileged to be present, as in the most glorious days of German romanticism, at the entry of a young woman endowed with all the gifts of seduction."

Because Kahlo destroyed all other evidence of her and Trotsky's affair, the painting is the only tangible evidence it took place.[7] Author and historian Hayden Herrera believes Kahlo gave the painting as a way of teasing Trotsky, especially by being dressed "fit to kill" along with wearing makeup. Another historian who specializes in Kahlo's life, Robin Richmond, has a different view. He thinks that Kahlo is dressed quite conservatively, and it was a way of her vying for Trotsky's attention. Richmond also thinks she was portraying another version of herself, and that the painting is "quite terrifying" because she was being calculative with its intent.[7]

In her book, Devouring Frida: The Art History and Popular Celebrity of Frida Kahlo, Margaret Lindauer writes these type of opinions are judging the painting by her looks. Richmond also considers Kahlo's infatuation with Trotsky more as a hero figure, rather than as a revolutionary, perhaps because she was too naïve to understand the facets of Trotskyism. Meanwhile, Trotsky is viewed as a towering figure and powerful man. The fact Kahlo added the date of the October Revolution on her painting suggests she was very aware of his political views, and supported them herself.[7]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 "Self-Portrait Dedicated to Leon Trotsky". Google Arts & Culture. Archived from the original on November 11, 2023. Retrieved November 13, 2023.

- ↑ Broude, Norman (2018). The Expanding Discourse: Feminism And Art History. Taylor & Francis. p. 399. ISBN 9780429972461.

- 1 2 "Self-Portrait Dedicated to Leon Trotsky". National Museum of Women in the Arts. Archived from the original on November 1, 2023. Retrieved November 12, 2023.

- 1 2 Walden, Victoria Grace (January 25, 2013). "Art - Sense of self". The Times Educational Supplement (5028): 44. ProQuest 1318728687. Archived from the original on November 14, 2023. Retrieved November 13, 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Kettenmann, Andrea (2003). Frida Kahlo, 1907-1954: Pain and Passion. Taschen. p. 41. ISBN 9783822859834. Archived from the original on 2023-11-14. Retrieved 2023-11-12.

- 1 2 3 "Passion, politics and painting: Seven facts uncovering the real Frida Kahlo". BBC Arts. March 7, 2023. Archived from the original on November 11, 2023. Retrieved November 13, 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Lindauer, Margaret A. (2014). Devouring Frida: The Art History and Popular Celebrity of Frida Kahlo. Wesleyan University Press. pp. 36–39. ISBN 9780819572097. Archived from the original on 2023-11-14. Retrieved 2023-11-12.

- 1 2 3 4 Zamora, Martha (1990). Frida Kahlo: Brush of Anguish. Chronicle Books. pp. 54–56. ISBN 9780811804851. Archived from the original on 2023-11-14. Retrieved 2023-11-13.

- ↑ Tuchman, Phyllis (November 2002). "Frida Kahlo". Smithsonian Magazine. Archived from the original on May 17, 2014. Retrieved January 5, 2024.

- ↑ Souter, Gerry (2019). Frida Kahlo: Beneath the Mirror. Parkstone International. ISBN 9781783104185. Archived from the original on 2023-11-14. Retrieved 2023-11-14.

- 1 2 3 Capps, Kriston (October 16, 2023). "Is a Women's Museum Still Relevant?". The New York Times. pp. C1. Archived from the original on November 13, 2023. Retrieved November 13, 2023.

- ↑ "Kahlo Sightings in Washington". The Washington Post. November 1, 2002. pp. C05. ProQuest 409373617. Archived from the original on November 14, 2023. Retrieved November 13, 2023.

- ↑ Schuman, Michael (March 30, 2008). "Framing Female Artists". St. Petersburg Times. pp. L4. ProQuest 264231838. Archived from the original on November 14, 2023. Retrieved November 13, 2023.

- 1 2 Burchard, Hank (August 26, 1994). "Latin Art Both Spare and Thoughtful". The Washington Post. pp. N55. ProQuest 307795715. Retrieved November 12, 2023.

- 1 2 Milroy, Sarah (June 30, 2001). "Three sisters of modernism". The Globe and Mail. pp. R5. ProQuest 384101252. Retrieved November 12, 2023.

- ↑ "The District". The Washington Post. July 7, 2007. pp. C12. ProQuest 410139050. Archived from the original on November 14, 2023. Retrieved November 13, 2023.

- ↑ "Collection highlights from the National Museum of Women in the Arts". The Washington Post. October 29, 2021. pp. T3. ProQuest 2587506916. Archived from the original on November 14, 2023. Retrieved November 13, 2023.

- ↑ Schuman, Michael (September 24, 2006). "Brush up on women in arts". The News & Observer. pp. 5H. Archived from the original on November 14, 2023. Retrieved November 13, 2023.

- 1 2 3 De La Torre, Josefina (February 1, 2021). "1937—Frida Kahlo, Self-Portrait Dedicated to Leon Trotsky". Fashion History Timeline. Fashion Institute of Technology. Archived from the original on November 11, 2023. Retrieved November 12, 2023.

External links

- Self-Portrait Dedicated to Leon Trotsky, National Museum of Women in the Arts

- Self-portrait Dedicated to Leon Trotsky, 1937, Google Arts & Culture