Sandy Island Beach State Park is a New York State park on the eastern shore of Lake Ontario. Its highlight is a 1,500-foot (460 m) natural sandy beach. The park is near the southern end of a notable 17-mile (27 km) length of sandy shoreline, coastal dunes, and wetlands (the Eastern Lake Ontario Dunes and Wetlands); a 1959 study noted that "The eastern end of Lake Ontario contains not only the finest beaches on the entire lake but also the finest wildlife habitat."[1]

The park's facilities include several lake swimming areas with lifeguards (in season), changing rooms and restrooms, and a concession stand; a parking fee is charged through the summer season. The park averages about 30,000 recorded visits each season.[2]

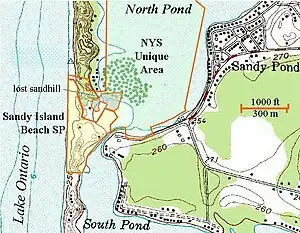

Prior to 2011, the park's area totaled 13 acres (5.3 ha). At that time, the adjacent 120-acre (49 ha) Sandy Island Beach Unique Area was a conservation area administered by the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. The Unique Area incorporated several additional acres of land near the park as well as most of the southern end of North Sandy Pond.[3][4] In 2011, administration and ownership of both the Sandy Island Beach Unique Area and the nearby Sandy Pond Beach Unique Area were transferred to the New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation to be incorporated into Sandy Island Beach State Park.[5][6] As of 2014, the park covers a total of 229 acres (93 ha)[7] in the Town of Richland in Oswego County.

"The hottest spot on the shoreline"

In the 1950s, Sandy Island Beach was opened as a private beach resort by LeGrande and Eva Smith. The resort became very popular. As Jack Major described it, "Overnight, Sandy Pond Beach – renamed Sandy Island Beach – became the place to go".[8] Ed Wyroba recalled that, through the 1960s, "it was the hottest spot on the shoreline. All our parents had gone there."[9] Following LeGrande Smith's death in 1966 and a decline in its popularity, the resort was closed in the early 1970s. The condition of the area deteriorated, which led to public discussions in 1976 of its possible purchase by Oswego County.[10] In 1980, 450 acres (180 ha) of the resort were purchased from the Smiths by Ed Wyroba and Dyke Riggs. They reopened the resort in 1981,[9] and operated it until 1991.[11] In 1999, The Nature Conservancy stepped in to help protect the property. In partnership with Oswego County and the State of New York, the Central & Western New York Chapter of The Nature Conservancy acquired the remaining 133 acres (54 ha) from the Riggs' heirs. The Conservancy then conveyed 13 acres (5.3 ha) on the beachfront to Oswego County for a park; 120 acres (49 ha) were purchased from the Conservancy by New York State for the Unique Area.[4][12] Oswego County operated the beach resort for several years and built a new bathhouse, picnic pavilions, and a boardwalk. In 2005, the County Park was transferred to the New York State Park system, which operates it.[13]

"The dune is moving"

North and south of Sandy Island Beach, the shoreline has high dunes that are up to 50 feet (15 m) higher than the level of Lake Ontario. Despite the fact that the high dunes are essentially pure sand, hardwood trees such as red oak and red maple grow on them.[14][15] The forested high dunes are one of the unusual features of the eastern Lake Ontario coastline. It can take 400 years for a hardwood forest to become established on a freshly formed dune.[16]

One high dune just north of the present boundary of Sandy Island Beach State Park is an example of the rapid changes that are possible in a sandy landscape. Jack Major wrote that "For many years the most popular spot on the beach was an open-faced sandhill that overlooked North Pond."[17] The topographic map from 1958 (see illustration and the annotation "lost sandhill") indicates that this dune was at least 50 feet (15 m) above lake level. In 1981, a "monster" dune was reported by a local newspaper as moving towards Sandy Pond.[18] The sandhill described by Major is much lower than it was in the 1970s; it has become a "low dune".[19]

Stable coastal dunes and sandhills are structures created by dune-building plants such as beachgrass and cottonwood trees. The loss of the high dune appears to have been the result of the destruction of its vegetation that occurred over the years, and in particular during the 1970s. At that time the area around Sandy Island Beach was privately owned, but wasn't staffed, occupied, or maintained.[10] In 1982, Dyke Riggs described the situation, "Bonfires fueled by trees on the beach and dune buggies, trucks and three-wheeled motorcycles careening around destroyed growth that holds the sand."[18]

Since 2000, the dune overlooking Sandy Island Beach was partially rebuilt and replanted with beachgrass by New York State.[19] At the nearby Sandy Pond Beach Unique Area, about 1–2 miles north of Sandy Island Beach, replanting has led to regrowth of low sand dunes.[20] Despite this success, natural regrowth of the full height of high dunes is thought to be unlikely. Robert Davis and Sandra Bonanno have written that "conditions no longer exist for the maintenance of high dunes - at least half of the high dunes at Sandy Pond have been reworked into low dunes since the time of the French traders."[21][22]

References

- ↑ Great Lakes Shoreline Recreation Area Survey (1959). Remaining Shoreline Opportunities in Minnesota, Wisconsin, Illinois, Indiana, Ohio, Michigan, Pennsylvania, New York. U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service.

- ↑ 2008 New York State Statistical Yearbook: 33rd Edition. Rockefeller Institute of Government. 2008. Table O-9. Retrieved January 23, 2010.

- ↑ "Central New York: Region 7". New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Archived from the original on October 19, 2008.

- 1 2 Hill, Mary Jo (May 14, 1999). "Sandy Island Beach plans await sale". The Syracuse Post-Standard. p. B1.

- ↑ "2011 Land Acquisition Report" (PDF). NYS Department of Environmental Conservation. 2011. Retrieved March 23, 2016.

- ↑ "ENB - Region 7 Notices 11/24/2010". NYS Department of Environmental Conservation. November 24, 2010. Archived from the original on April 4, 2015. Retrieved March 23, 2016.

- ↑ "Section O: Environmental Conservation and Recreation, Table O-9". 2014 New York State Statistical Yearbook (PDF). The Nelson A. Rockefeller Institute of Government. 2014. p. 674. Retrieved March 23, 2016.

- ↑ Major, Jack (2008). "Sandy Pond 5: The Rise and Fall". Archived from the original on May 9, 2008. The webpage is part of a larger website that describes one family's experiences at Sandy Pond over 80 years.

- 1 2 Knobel, Andy (August 19, 1981). "Sandy Island Beach awakens from sleep". The Syracuse Post-Standard. p. Accent p. 7.

- 1 2 "County may purchase beach". The Syracuse Post Standard. April 28, 1976. p. 19-N.

- ↑ Hill, Mary Jo (July 31, 1992). "Beach Offers Sun, Sand, and Lots of Trash". The Syracuse Post-Standard. p. B1.

- ↑ Oswego County real estate transaction records for parcel 027.14-01-01.2 (Unique Area) and parcel 027.13-01-01 (State Park). Online versions accessed 2009-01-26.

- ↑ Gibson, Wendy; Jimenez, Catherine (June 24, 2006). "State Parks Commissioner Opens Sandy Island Beach". New York State Office of Parks, Recreation, and Historic Preservation. Archived from the original on December 25, 2010.

- ↑ Bonanno, Sandra E.; White, David G. (September 1993). "Eastern Lake Ontario Sand Dunes: An Overview of their Flora". New York Sea Grant Extension. Archived from the original on June 23, 2010.

- ↑ Bonanno, Sandra E.; Leopold, Donald J.; St. Hillaire, Lucy R. (1998). "Vegetation of a freshwater dune barrier under high and low recreational uses" (PDF). Journal of the Torrey Botanical Society. Torrey Botanical Society. 125 (1): 40–50. doi:10.2307/2997230. JSTOR 2997230.

- ↑ Lichter, John (1998). "Primary succession and forest development on coastal Lake Michigan sand dunes" (PDF). Ecological Monographs. 4 (4): 487–510. doi:10.1890/0012-9615(1998)068[0487:PSAFDO]2.0.CO;2. hdl:2027.42/116367.

- ↑ Major, Jack (2008). "Sandy Pond 2: Head for the Hill". Archived from the original on May 11, 2008.

- 1 2 McGuire, Dan (July 14, 1982). "Monster sand dune moving inland from lake". The Syracuse Post-Standard. p. D1.

- 1 2 Major, Jack (2008). "Sandy Pond 9: Update". Archived from the original on May 15, 2008.

- ↑ Gifford, Aaron (September 21, 2000). "Answer is Blowin' in the Wind: Group's planting effort restores dunes at Sandy Pond". The Syracuse Post Standard. p. B-1.

- ↑ Davis, Robert; Bonanno, Sandra (October 10, 1995). "Sandy Pond Beach Management Plan" (PDF). NYS Dept. of Environmental Conservation and The Nature Conservancy. p. 6. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 27, 2010. Retrieved January 26, 2010.

- ↑ The eastern Lake Ontario high dunes are apparently relics of the era when the lake level was perhaps 30 feet (9.1 m) lower than at present, which is also the era in which the present ponds were river mouths. Presumably, there was much more blowing sand at that time, permitting the dunes to grow fairly tall. The amount of sand that blows annually onto the coastal dunes appears to be insufficient to feed the growth of high dunes.

External links

- "Sandy Island Beach State Park". New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation. Retrieved March 23, 2016.

- "Sandy Island Beach". New York Sea Grant Extension. Retrieved July 23, 2010.