The rosary is one of the most notable features of popular Catholic spirituality.[1] According to Pope John Paul II, rosary devotions are "among the finest and most praiseworthy traditions of Christian contemplation."[2] From its origins in the twelfth century the rosary has been seen as a meditation on the life of Christ, and it is as such that many popes have approved of and encouraged its recitation.

Use of repetitive prayer formulas goes far back in Christian history, and how these passed into the rosary tradition is not clear. It is clear that the 150 beads (Hail Marys) originated from the 150 Psalms prayed from the Hebrew Psalter. The rosary was a way for the ordinary faithful to simulate the meditation of the monks from the hand-printed Psalter. The second half of the Hail Mary, the petition to Mary, appeared for the first time in the catechism of Peter Canisius in 1555 in the Counter-Reformation period, in reaction against Protestant criticism of some Catholic beliefs.[3][4]

Following the establishment of the first rosary confraternities in the fifteenth century, the devotion to the rosary spread rapidly throughout Europe. From the sixteenth century onwards, rosary recitations often involved "picture texts" that assisted meditation. Such imagery continues to be used to assist in rosary meditations.

Origins

There are differing views on the origin of the rosary, with some traditions attributing it to Dominic who integrated it into Dominican devotion, but evidence shows its existence prior to his time, and a gradual development over centuries of practice.[5][6]

| Part of a series on the |

| Rosary of the Catholic Church |

|---|

|

| Overview |

| Prayers and promises |

| Writings |

| People and societies |

|

|

The practice of meditation during the praying of repeated Hail Marys goes back at least to the 1400s in Germany and the Carthusian monk Dominic of Prussia who died in 1461, just as the Dominicans Alanus de Rupe and James Sprenger had started to promote the rosary.

By the 1500s the practice of meditation during the rosary had spread across Europe. Bartolomeo Scalvo's Meditationi del Rosario della Gloriosa Maria Virgine (i.e. Meditations on the Rosary of the Glorious Virgin Mary) printed in 1569 for the rosary confraternity of Milan provided an individual meditation to accompany each bead or prayer.[7]

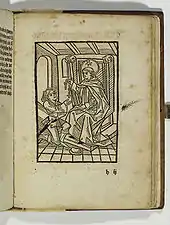

Alanus de Rupe encouraged the rosary to be prayed in front of an image of Christ or the Virgin Mary. This style of meditation later resulted in meditation using narrative images, the first of which was eventually printed by Dinkmut in Ulm, Germany. The use of "image directed rosary meditation" soon gained popularity and at the end of the 16th century the most widely used rosary meditation in Germany was not a written one, but a picture text.[8]

During the 16th century, the use of images as a form of religious instruction and indoctrination via silent preaching (muta predicatio) was promoted by Gabriele Paleotti in his "Discourse on Sacred and Profane Images."[9] As the use of devotional images came to be seen as the "literature of the layman", Paleotti's goal of the transformation of Christian life through the use of sacred images fostered and promoted Marian devotions including the Rosary.[10]

By the 17th century, the 15 wood cut images of the picture rosary had become very popular and rosary books began to use them across Europe. In contrast to written rosary meditations, the picture texts changed little and the same set of images appeared in woodcuts, engravings, and devotional panels for over a hundred and fifty years.[8]

Meditation and contemplation

_-_Walters_3745.jpg.webp)

The word meditation comes from the Latin word meditari which means to concentrate.[12] In 1577 in her book Interior Castle (Mansions 6, Chapter 7), Teresa of Avila, a Doctor of the Church, defined the general approach to Christian meditation as follows:[13]

By meditation I mean prolonged reasoning with the understanding, in this way. We begin by thinking of the favor which God bestowed upon us by giving us His only Son; and we do not stop there but proceed to consider the mysteries of His whole glorious life.

This perspective can be viewed as the basis of most scriptural rosary meditations.[14] Scriptural meditations on the rosary build on the Christian tradition of Lectio Divina (divine reading) as a way of using the Gospel to start a conversation between the soul and Christ.

Christian meditation is differentiated from contemplation which involves a higher level of focus and detachment from the surroundings and environment.[15] The word contemplation (coming from the Latin root templum, i.e. to cut or divide) means to separate oneself from the environment. John of the Cross called contemplation "silent love" and viewed it as an intimate union with God.[16] Contemplation with the rosary is the next step beyond scriptural meditation. This does not mean that the Gospel is ignored during contemplation, but that the focus moves toward the love of God.[17]

In his 2002 encyclical Rosarium Virginis Mariae, Pope John Paul II emphasized that the final goal of Christian life is to be transformed, or "transfigured", into Christ, and the rosary helps believers come closer to Christ by contemplating Christ. He characterized the contemplative aspects of the rosary as follow: "To recite the rosary is nothing other than to contemplate with Mary the face of Christ."[18] And quoting Pope Paul VI he reiterated the importance of contemplation, stating that without contemplation, the rosary is "a body without soul."[19]

The rosary may be prayed anywhere, but as in many other devotions its recitation often involves some sacred space or object, such as an image or statue of the Virgin Mary.[20] Anyone can begin to pray the rosary, but repeated recitations over a period of time result in the acquisition of skills for meditation and contemplation.[21]

Teachings of the saints

In the sixteenth century, Peter Canisius, a Doctor of the Church, who is credited with adding to the Hail Mary the sentence "Holy Mary, Mother of God, pray for us sinners," was an ardent advocate of the rosary and its confraternities.[22] He developed and stressed the importance of the meditative aspects of the rosary and was one of the first among the early Jesuits to teach that the principle virtue of each mystery of the rosary should be applied to daily life.[23]

Louis de Montfort, one of the early proponents of the field of Mariology, was a strong proponent of the rosary. He joined the Third Order of the Dominicans in 1710, soon after being ordained a priest, in order to preach the rosary.[24] His books Secret of the Rosary and True Devotion to Mary influenced the Mariological views of several popes. In Secret of the Rosary he taught how "focus, respect, reverence, and purity of intention" are essential in praying the rosary. He stated that it is not the length of a prayer that matters, but the fervor, purity, and respect with which it is said, e.g. a single meditatively said Hail Mary is worth many that are badly said. In the Secret of the Rosary, he also taught how to fight distractions to achieve the proper mindset for meditating with the rosary.[25]

In the eighteenth century, Alphonsus Liguori, a Doctor of the Church, also emphasized the need for proper devotion when praying the rosary. In The Glories of Mary he wrote that the Virgin Mary would be more pleased with five decades of the rosary said slowly with devotion than with fifteen said in a hurry and with little devotion. He recommended that the rosary should be said kneeling before an image of the Virgin Mary and before each decade to make an act of love to Jesus and Mary and ask them for a particular grace.[26]

Padre Pio was a firm believer in meditation in conjunction with the rosary and said: "Love the Madonna and pray the rosary, for her rosary is the weapon against the evils of the world today. ...The person who meditates and turns his mind to God, who is the mirror of his soul, seeks to know his faults, tries to correct them, moderates his impulses, and puts his conscience in order."[27]

Papal views

In 1569 Pope Pius V, a Dominican himself, officially established the devotion to the rosary in the Catholic Church with the papal bull Consueverunt Romani Pontifices and in 1571 called for all of Europe to pray the rosary for victory at the Battle of Lepanto.[28][29][30]

Pope Leo XIII promulgated ten encyclicals on the rosary and instituted the Catholic custom of daily rosary prayer during the month of October. In 1883 he also created the Feast of Queen of the Holy Rosary.[31] In Laetitiae sanctae Leo XIII wrote that he was "convinced that the rosary, if devoutly used, is of benefit not only to the individual but society at large."[32]

Pope Pius XII emphasized the benefits of rosary meditations in his encyclical Ingruentium Malorum and wrote:

And truly, from the frequent meditation on the Mysteries, the soul little by little and imperceptibly draws and absorbs the virtues they contain, and is wondrously enkindled with a longing for things immortal, and becomes strongly and easily impelled to follow the path which Christ Himself and His Mother have followed.[33]

The popes of the 19th and 20th centuries up to Pope Paul VI stressed the Mariological aspects of the rosary. However, in 1974 in his Apostolic Exhortation Marialis Cultus, Pope Paul VI focused more on its traditional meditative, Christocentric nature and stated: "The rosary is therefore a prayer with a clearly Christological orientation."[34]

| Part of a series on the |

| Mariology of the Catholic Church |

|---|

|

|

|

Pope John Paul II built on the Christocentric theme of Pope Paul VI,[35] stating: "The rosary, though clearly Marian in character, is at heart a Christocentric prayer. In the sobriety of its elements, it has all the depth of the Gospel message in its entirety, of which it can be said to be a compendium."[36]

He further emphasized the contemplative nature of the rosary and stated that: "The rosary belongs among the finest and most praiseworthy traditions of Christian contemplation."[2]

Apparitions

References to the rosary have been part of a number of reported Marian Apparitions spanning two centuries. The reported messages from these apparitions have influenced the spread of rosary devotions worldwide.[37][38]

Bernadette Soubirous stated that in the first apparition of Our Lady of Lourdes in 1858, the Virgin Mary had a rosary with her and that Bernadette prayed the rosary in her presence then and during subsequent apparitions.[39] The Rosary Basilica was built at that site in Lourdes in 1899.

The rosary was prominently featured in the apparitions of Our Lady of Fátima reported by three Portuguese children in 1917. The reported Fatima messages place a strong emphasis on the Rosary and in them the Virgin Mary is identified as The Lady of the Rosary. According to Lucia Santos (one of the three children) in one of the apparitions the Virgin Mary has a rosary in one hand and a Brown scapular in the other hand. Reports of the Fatima apparitions helped spread rosary devotions and a Fatima prayer is now often added to the end of rosary recitations.[40][41] The Basilica of Our Lady of the Rosary, Fatima, was built at that site in 1953 and has fifteen altars, each dedicated to a mystery of the rosary.[42]

In January 1933 an eleven-year-old peasant girl called Mariette Beco reported apparitions of the Virgin Mary in Banneux, Belgium, which became known as the Virgin of the Poor. Mariette reported seeing the Virgin Mary with a rosary in hand. Mariette reported that the apparition repeated three days later after she went outside her house and prayed the rosary.[43] The reports of this apparition, also known as Our Lady of Banneux, were approved by the Holy See in 1949.[44][45][46][47]

In the reported messages of Our Lady of Akita, Agnes Sasagawa stated that in 1973 she was told by the Virgin Mary: "Pray very much the prayers of the rosary. I alone am able still to save you from the calamities which approach." In 1984, the Bishop of Niigata, John Shojiro Ito, authorized the veneration of the Holy Mother of Akita "...while awaiting for the Holy See to publish a definitive judgment on this matter."[48]

Gallery of art and architecture

Antonello da Messina, 15th century

Antonello da Messina, 15th century Guido Reni, c. 1596

Guido Reni, c. 1596 Lorenzo Lotto, 1539

Lorenzo Lotto, 1539 Rosary Madonna (detail) Josef Mersa ca 1905

Rosary Madonna (detail) Josef Mersa ca 1905

Holy Rosary Church, Wysokie Kolo, Poland

Holy Rosary Church, Wysokie Kolo, Poland

Our Lady of the Rosary, Merelbeke, Belgium

Our Lady of the Rosary, Merelbeke, Belgium

See also

Notes

- ↑ McGrath, Alister E., Christian Spirituality: An Introduction, 1995 ISBN 0-631-21281-7 p. 16

- 1 2 Pope John Paul II, Rosarium Virginis Mariae § 5, Vatican

- ↑ Petrus Canisius, CATECHISMI Latini et Germanici, I, ( ed Friedrich Streicher, S P C CATECHISMI Latini et Germanici, I, Roma, Munich, 1933, I, 12

- ↑ Finley, Mitch. The Seeker's Guide to Saints, 2000, ISBN 0-8294-1350-2 p. 73

- ↑ Beebe, Catherine. St. Dominic and the Rosary ISBN 0-89870-518-5

- ↑ Thurston, Herbert, and Andrew Shipman. "The Rosary." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 13. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1912. 7 Oct. 2014

- ↑ Getz, Christine Suzanne. Music in the collective experience in sixteenth-century Milan, p.261, 2006 ISBN 0-7546-5121-5

- 1 2 Winston-Allen 1997, pp. 32–34.

- ↑ Mitchell, Nathan. The Mystery of the Rosary: Marian Devotion and the Reinvention of Catholicism, pp.37-42, 2009 ISBN 0-8147-9591-9

- ↑ Marino, Adrian. The biography of "The idea of literature" from antiquity to the Baroque, p.46, 1996 ISBN 0-7914-2894-X

- ↑ "Devotion (Contemplation)". The Walters Art Museum.

- ↑ Antonisamy, F. An introduction to Christian spirituality, p.76, 2000 ISBN 81-7109-429-5

- ↑ Teresa of Avila, Interior Castle 1979 ISBN 0-8091-2254-5 page 147

- ↑ Walls, Ronald. This Is Your Mother: The Scriptural Roots of the Rosary, p.4, 2003 ISBN 0-85244-403-6

- ↑ Poulain, Augustin. "Contemplation." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 4. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1908. 7 Oct. 2014

- ↑ Provencher, Maureen. Mysteries in My Hands: Young People, Life and the Rosary, p.28, 2005 ISBN 0-88489-832-6

- ↑ Storey, William George. The Complete Rosary: A Guide to Praying the Mysteries, p.59, 2006 ISBN 0-8294-2351-6

- ↑ Rosarium Virginis Mariae, § 3

- ↑ Madore 2004, pp. 18–19.

- ↑ Raitt, Jill. World spirituality, pp.100-101, 1987 ISBN 0-7102-1313-1

- ↑ Griffin, Emilie. Simple Ways to Pray: Spiritual Life in the Catholic Tradition, p.85, 2005 ISBN 0-7425-5084-2

- ↑ Braunsberger, Otto. "Blessed Peter Canisius." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 11. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1911. 7 Oct. 2014

- ↑ Stravinskas, Peter M. J., The Catholic Answer Book of Mary, p.131, 2000 ISBN 0-87973-347-0

- ↑ Burke, Raymond. Mariology: A Guide for Priests, Deacons,seminarians, and Consecrated Persons, p.708, Queenship Publishing, 2008, ISBN 1-57918-355-7

- ↑ de Montfort, Louis. The Secret of the Rosary, "Roses" (i.e. chapters) 41-43, Tan Books & Publisher, 1976. ISBN 978-0-89555-056-9,

- ↑ Liguori, Alphonsus. The Glories of Mary, p.481, Liguori Publications, 2000, ISBN 0-7648-0664-5

- ↑ Kelly, Liz. The Rosary: A Path Into Prayer, pp.79, 86, 2004 ISBN 0-8294-2024-X

- ↑ Scaperlanda, Maria Ruiz. The Seeker's Guide to Mary, p.151, 2002 ISBN 0-8294-1489-4

- ↑ Cizik, Ladis J. "Our Lady and Islam: Heaven's Peace Plan", EWTN

- ↑ Chesterton, Gilbert Keith, Lepanto, Ignatius Press, 2004, ISBN 1-58617-030-9

- ↑ Remigius Baumer, 1988, Marienlexikon, St. Ottilien, pp.41

- ↑ Stravinskas 2000, p. 135.

- ↑ Pope Pius XII. Ingruentium Malorum, Vatican

- ↑ Pope Paul VI, Marialis Cultus § 46

- ↑ Fahlbusch & Bromiley 2005, p. 757.

- ↑ Rosarium Virginis Mariae § 1

- ↑ Shamon, Albert J. M., The Power of the Rosary, p.5, CMJ Publishers, 2003. ISBN 1-891280-10-4

- ↑ Miller, John D., Beads and prayers: the rosary in history and devotion, p.151, 2002 ISBN 0-86012-320-0

- ↑ McEachern, Patricia A., A holy life: the writings of Saint Bernadette of Lourdes, p.205, 2005 ISBN 1-58617-116-X

- ↑ de Marchi, John. The True Story of Fatima, 1952, EWTN

- ↑ Santos, Lucia., 1976, Fatima in Lucia's Own Words, Ravengate Press, 1976, ISBN 0-911218-10-6

- ↑ Hole, Abigail. Portugal, p.277, Charlotte Beech 2005 ISBN 1-74059-682-X

- ↑ Scaperlanda 2002, p. 124.

- ↑ Ball, Ann. Encyclopedia of Catholic Devotions and Practices, p.641, 2003, ISBN 0-87973-910-X

- ↑ van Houtryve, La Vierge des Pauvres, Banneux, 1947

- ↑ Matthew Bunson, The Catholic Almanac, p. 123, 2008, ISBN 978-1-59276-441-9

- ↑ Stravinskas, Peter. Our Sunday Visitor's Catholic Encyclopedia, p.124, 1998, ISBN 0-87973-669-0 page 124

- ↑ "Apparitions of the Blessed Virgin Mary in Akita, Japan to Sr. Agnes Sasagawa

References

- Fahlbusch, Erwin; Bromiley, Geoffrey William (2005). The Encyclopedia of Christianity. Vol. 4. ISBN 0-8028-2416-1.

- Madore, George (2004). The Rosary with John Paul II. Alba House. ISBN 2-89420-545-7.

- Scaperlanda, Maria Ruiz (2002). The Seeker's Guide to Mary. ISBN 0-8294-1489-4.

- Stravinskas, Peter M. J. (2000). The Catholic Answer Book of Mary. ISBN 0-87973-347-0.

- Winston-Allen, Anne (1997). Stories of the rose: the making of the rosary in the Middle Ages. ISBN 0-271-01631-0.

Further reading

External links

- Saint Bonaventure (1473–1475). Psalterium maius Beatae Virginis Mariae (in Latin). Basel: Martin Flack. doi:10.3931/e-rara-18470. Archived from the original on July 23, 2018.

- Saint Bonaventure (1642). Psalterivm B. Mariæ Virginis (with translation in Spanish) (in Latin and Spanish). Munich: Melchor Segen. Archived from the original on July 22, 2018. Retrieved Jul 22, 2018.

- Psalterium dive Virginis Mariae (in Latin). Translated by Petrarca. Anthoine Verard libraire. 1497–1499. p. 101. Retrieved Jul 22, 2018 – via Bibliothèque nationale de France.