Rocamadour

| |

|---|---|

| |

.svg.png.webp) Coat of arms | |

Location of Rocamadour | |

Rocamadour  Rocamadour | |

| Coordinates: 44°48′01″N 1°37′07″E / 44.8003°N 1.6186°E | |

| Country | France |

| Region | Occitania |

| Department | Lot |

| Arrondissement | Gourdon |

| Canton | Gramat |

| Government | |

| • Mayor (2020–2026) | Dominique Lenfant[1] |

| Area 1 | 49.42 km2 (19.08 sq mi) |

| Population | 611 |

| • Density | 12/km2 (32/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+01:00 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+02:00 (CEST) |

| INSEE/Postal code | 46240 /46500 |

| Elevation | 110–364 m (361–1,194 ft) (avg. 279 m or 915 ft) |

| 1 French Land Register data, which excludes lakes, ponds, glaciers > 1 km2 (0.386 sq mi or 247 acres) and river estuaries. | |

Rocamadour (French pronunciation: [ʁɔkamaduʁ]; Rocamador in Occitan) is a commune in the Lot department in southwestern France. It lies in the former province of Quercy.

Rocamadour[3] has attracted visitors for its setting in a gorge above a tributary of the River Dordogne and especially for its historical monuments and its sanctuary of the Blessed Virgin Mary, which for centuries has attracted pilgrims from many countries, among them kings, bishops and nobles.[4]

The town below the complex of monastic buildings and pilgrimage churches, traditionally dependent on the pilgrimage site and now on the tourist trade, lies near the river on the lowest slopes; it gives its name to Rocamadour, a small goat's-milk cheese that was awarded AOC status in 1996.

Geography

Location and access

Rocamadour is located in the Lot department in the far north of the Occitanie region. Close to Périgord and the Dordogne valley, Rocamadour is at the heart of the Parc naturel régional des Causses du Quercy , a regional nature park. Rocamadour is located 36 km NNE of Cahors by road. It is located on the right bank of the Alzou.

Rocamadour can be reached by car from the A20 autoroute, or by train: Gare de Rocamadour-Padirac on the Brive-la-Gaillarde–Toulouse (via Capdenac) railway.

Rocamadour is served by two regional airports that provide easy access to the Dordogne Valley. The Aéroport Brive Vallée de la Dordogne (BVE) is located only a few kilometres from many of the region's star attractions whilst the Aéroport Bergerac Dordogne Périgord (EGC) is situated just 6 km south of Bergerac.

Hamlets

The territory of the commune of Rocamadour includes several hamlets: L'Hospitalet, Les Alix, Blanat, Mas de Douze, Fouysselaze, Magès, La Fage, La Gardelle, Chez Langle, La Vitalie, Mayrinhac-le-Francal.

Toponymy

The ancient forms of Rocamadour are Rocamador from 968, Rupis Amatoris in 1186. According to Dauzat, the toponym comes from the name of a saint, Amator.[5]: 569

According to Gaston Bazalgues, the toponym Rocamadour is a medieval form which originates from Rocamajor. Roca pointed to a rock shelter and major spoke of its importance. This name would have been Christianized from 1166 with the invention of the false hagiotoponym Saint Amadour or Saint Amateur. In 1473, according to the monograph of Edmond Albe, the place was named the castling of Saint Amadour. In 1618, on a map of the diocese of Cahors by Jean Tarde, the name of Roquemadour appeared.[6]: 119

In 1166, the relics of Saint Amadour was discovered: a perfectly preserved body was buried in the heart of the Virgin Mary sanctuary, in front of the entrance to the miraculous chapel. The body of Saint Amadour was taken out of the ground and then exposed to the pilgrims. The body was burned during the Wars of Religion and today only fragments of bone remain, presently on view in the crypt of Saint-Amadour.

The locality L'Hospitalet, overlooking Rocamadour, has a name from espitalet which meant small hospital and has Latin origin hospitalis. This reception centre was founded in 1095 by Dame Hélène de Castelnau.[6]

Sights

Rocamadour was a dependency of the abbey of Tulle to the north in the Bas Limousin. The buildings of Rocamadour (from ròca, cliff and saint Amador) rise in stages up the side of a cliff on the right bank of the Alzou, which runs between rocky walls 120 metres (390 ft) in height.

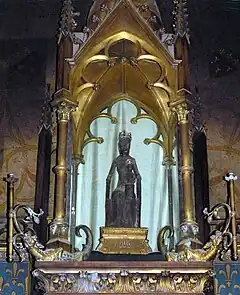

Flights of steps ascend from the lower town to the churches, a group of massive buildings half-way up the cliff. The chief of them is the pilgrimage church of Notre Dame (rebuilt in its present configuration from 1479), containing the cult image at the centre of the site, a wooden Black Madonna reputed to have been carved by Saint Amator (Amadour) himself. The small Benedictine community continued to use the small twelfth-century church of Saint-Michel, above and to the side. Below, the pilgrimage church opens onto a terrace where pilgrims could assemble, called the Plateau of St Michel, where there is a broken sword said to be a fragment of Durandal, once wielded by the hero Roland.

The interior walls of the church of St Sauveur are covered with paintings and inscriptions recalling the pilgrimages of celebrated people. The subterranean church of St Amadour (1166) extends beneath St Sauveur and contains relics of the saint. On the summit of the cliff stands the château built in the Middle Ages to defend the sanctuaries.

History

Prehistory

Rocamadour and its many caves already housed people in the Paleolithic as shown in the cave drawings of the Grotte des Merveilles. The Grotte de Linars cave and its porch served as an underground necropolis and a habitat in the Bronze Age. The vestiges are deposited in the museum at Cabrerets and at the town hall in Rocamadour.

During the Iron Age, the Cadurques people arrived from middle Germany. In the eighth century BC., they colonised the current Lot department, using their iron weapons. The remains of a village, in the Salvate valley near Couzou, were found during work. An oppidum perched on the heights of the Alzou valley, downstream from Tournefeuille, is perhaps linked to the fight of the Gauls against the Roman troops during the Gallic war.[7]

Middle ages

The beginnings and the influence

The three levels of the village of Rocamadour date from the Middle Ages and they reflect the three orders of society: the knights above, linked to religious clerics in the middle and the lay workers down near the river.

Rare documents mention that in 1105 a small chapel was built in a shelter of the cliff at a place called Rupis Amatoris, at the limit of the territories of the Benedictine abbeys of Saint-Martin at Tulle and Saint-Pierre at Marcilhac-sur-Célé.

In 1112, Eble de Turenne, Abbot of Tulle settled in Rocamadour. In 1119, the first donation was made by Eudes, Comte de la Marche. In 1148, a first miracle was announced. The pilgrimage to the Virgin Mary attracted crowds. The statue of the Black Madonna dates from the 12th century. Géraud d'Escorailles (abbot from 1152 to 1188) built the religious buildings, financed by donations from visitors. The works were finished at the end of the 12th century.

Rocamadour already enjoyed European fame as evidenced by the 12th-century book Livre des Miracles[8] written by a monk from the sanctuary and received many pilgrims. In 1159, Henry II of England, husband of Eleanor of Aquitaine, came to Rocamadour to thank the Virgin for her healing.

In 1166, wanting to bury a resident, they discovered an intact body, presented as that of Saint Amadour. Rocamadour had found its saint. At least four stories, more or less tinged with legend, presented Saint Amadour as being close to Jesus.

In 1211, the pontifical legate during the Albigensian Crusade, Arnaud Amalric, came to spend the winter in Rocamadour. In addition, in 1291, Pope Nicholas IV granted three bulls and forty day indulgences for site visitors. The end of the 13th century saw the height of Rocamadour's influence and the completion of the buildings. The castle was protected by three towers, a wide moat and numerous lookouts.[7]

Decline

In 1317, the monks left Rocamadour. The site was then administered by a chapter of canons appointed by the bishop. In the fourteenth century, a cooling climate, famines, epidemics like the Black Death ravaged Europe.

In 1427, reconstruction was started, but without financial or human resources. A huge rock crushed the Notre-Dame chapel which was rebuilt in 1479 by Denys de Bar, Bishop of Tulle.[9]

Subsequently, during the French Wars of Religion, the iconoclastic passage of Protestant mercenaries in 1562 caused the destruction of religious buildings and their relics.[10] The canons describe, in a petition to Pope Pius IV in 1563, the damage caused: “They have, oh pain! all trashed; they burned and looted its statues and paintings, its bells, its ornaments and jewels, all that was necessary for divine worship ... ”. The relics were desecrated and destroyed, including the body of Saint Amadour. According to witnesses, the Protestant Captain Jean Bessonia broke it with the smith's hammer, saying: "I am going to break you, since you did not want to burn". Captains Bessonie and Duras would draw, for the benefit of the Prince of Condé's army, the sum of 20,000 pounds from everything that made up the treasure of Notre-Dame since the 12th century.[11]

The site was again looted during the French Revolution.

Contemporary Rocamadour

Since the early 20th century, Rocamadour has become more of a tourist destination than a pilgrimage center, although pilgrimage continues and remains important. Rocamadour's environs are now marked by several animal parks, including Le Rocher des Aigles and Le Forêt des Singes (a bird of prey park and a monkey park, respectively) and also hosts an annual cheese festival. Outdoor activities and hot air ballooning are popular among visitors. The site's gravity-defying churches and Black Madonna statue remain a spiritual draw for both Catholic pilgrims and for visitors who practice earth-based or New Age religions, being drawn to stories of Rocamadour's "strange energies" and pre-Christian origins.[12]

Gallery

Chapelle de l'Hospitalet in Rocamadour

Chapelle de l'Hospitalet in Rocamadour

Pilgrimage

A legend supposed to explain the origin of this pilgrimage has given rise to controversies between critical and traditional schools, especially in recent times. A vehicle by which the legend was disseminated and pilgrims drawn to the site was The Miracles of Our Lady of Rocamadour, written ca. 1172,[13] an example of the miracula, or books of collected miracles, which had such a wide audience in the Middle Ages.

According to the founding legend, Rocamadour is named after the founder of the ancient sanctuary, Saint Amator, identified with the Biblical Zacheus, the tax collector of Jericho mentioned in Luke 19:1-10, and the husband of St. Veronica, who wiped Jesus' face on the way to Calvary.

Driven out of Palestine by persecution, St. Amadour and St. Veronica embarked in a frail skiff and, guided by an angel, landed on the coast of Aquitaine, where they met Bishop St. Martial, another disciple of Christ who was preaching the Gospel in the south-west of Gaul.

After journeying to Rome, where he witnessed the martyrdoms of St Peter and St Paul, Amadour, having returned to France, on the death of his spouse, withdrew to a wild spot in Quercy where he built a chapel in honour of the Blessed Virgin, near which he died a little later.[14]

This account, like most other similar legends, does not make its first appearance till long after the age in which the chief actors are deemed to have lived. The name of Amadour occurs in no document previous to the compilation of his Acts, which on careful examination and on an application of the rules of the cursus to the text cannot be judged older than the 12th century. It is now well established that Saint Martial, Amadour's contemporary in the legend, lived in the 3rd not the 1st century, and Rome has never included him among the members of the Apostolic College. The mention, therefore, of St Martial in the "Acts of St Amadour" would alone suffice, even if other proof were wanting, to prove them doubtful.

The untrustworthiness of the legend has led some recent authors to suggest that Amadour was an unknown hermit or possibly St. Amator, Bishop of Auxerre, but this is mere hypothesis, without any historical basis. The origin of the sanctuary of Rocamadour, lost in antiquity, is thus set down along with fabulous traditions which cannot bear up to sound criticism. After the religious manifestations of the Middle Ages, Rocamadour, as a result of war and the French Revolution, had become almost deserted. In the mid-nineteenth century, owing to the zeal and activity of the bishops of Cahors, it seems to have revived.[14]

Rocamadour is classed as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO as part of the St James’ Way pilgrimage route.[15]

Cultural references

In her book-length poem, "Solitude," Vita Sackville-West uses Rocamadour in her dedication, as site and setting for inspiration.

The composer Francis Poulenc wrote in 1936 Litanies à la Vierge Noire (Litanies to the Black Virgin) after a pilgrimage to the shrine.

Rocamadour inspired 20th-century Latin American novelists Julio Cortázar and Giannina Brashi who lived in France for some time and wrote in Spanish about immigrants, expatriates, and tourists. In Cortazar's opus "Hopscotch", the sad heroine La Maga has a baby boy named Rocamadour who dies in his sleep. The dead baby Rocamadour is also a character in Giannina Braschi's novel "Yo-Yo Boing!".

Rocamadour is mentioned in Michel Houellebecq book Soumission (2015).

Famous pilgrims

- Eleanor of Aquitaine

- Henry II of England

- Blanche of Castile

- Louis IX of France

- Charles IV of France

- Louis XI of France

- Jacques Cartier. In the St. Lawrence Valley (in present-day Quebec province) in February 1536 the French explorer prayed to the Blessed Virgin under the title of Our Lady of Rocamadour that he would make a pilgrimage to her shrine "if he should obtain the grace to return to France safely."

- Francis Poulenc

- Sœur Emmanuelle

Notes

- ↑ "Répertoire national des élus: les maires". data.gouv.fr, Plateforme ouverte des données publiques françaises (in French). 9 August 2021.

- ↑ "Populations légales 2021". The National Institute of Statistics and Economic Studies. 28 December 2023.

- ↑ The "roc or rocca of Amadour".

- ↑ The modern account is J. Rocacher, Rocamadour et son pèlerinage: étude historique et archéologique, 2 vols. (Toulouse) 1979.

- ↑ Dauzat, Albert; Rostaing, Charles (1989). Dictionnaire étymologique des noms de lieux en France (in French). Paris: Librairie Guénégaud. p. 738. ISBN 2-85023-076-6.

- 1 2 Bazalgues, Gaston (June 2002). À la découverte des noms de lieux du Quercy. Toponymie lotoise (in French). Gourdon. p. 127. ISBN 2-910540-16-2.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - 1 2 Cheveau, Michelle (1998). Rocamadour: Une cité en équilibre (in French). Concots. p. 430. ISBN 2-9510050-6-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Le livre de Notre-Dame de Rocamadour au XIIe siècle (in French). Moine du sanctuaire de Rocamadour. Toulouse: Le Pérégrinateur. 1996. ISBN 2910352048.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)CS1 maint: others (link) - ↑ Cranga, Y. & F. (1997). "L'escargot dans le midi de la France, approche iconographique" (PDF) (in French). Retrieved 22 July 2009.

- ↑ Rosary, Eugène (1864). Les Pèlerinages de France (in French). Mégard et Ce.

- ↑ Montaigu, Henry (8 April 1974). Rocamadour ou la pierre des siècles. Haut lieux de spiritualité. Éditions SOS. pp. 108–9. ISBN 2-7185-0774-8.

- ↑ Weibel, Deana L. (2022). A sacred vertigo : pilgrimage and tourism in Rocamadour, France. Lanham, Maryland. ISBN 978-1-7936-5033-7. OCLC 1285370679.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Marcus Graham Bull, The Miracles of Our Lady of Rocamadour: Analysis and Translation (1999) justifies his dating of 1172 and 1173 (for book III), an uncharacteristically rapid assembly of miracle accounts, which were commonly assembled over decades (p. 27); the collection contains 126 miracles in three books.

- 1 2 Clugnet, Léon. "Rocamadour." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 13. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1912. 27 Apr. 2013

- ↑ "Rocamadour", France Guide, French Government Tourist Office

Relevant literature

- Weibel, Deana L. A Sacred Vertigo: Pilgrimage and Tourism in Rocamadour, France. Rowman & Littlefield, 2022.

External links and references

- Tourist office website

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Rocamadour". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 23 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 425.

- Notre Dame De Rocamadour (French only) https://web.archive.org/web/20150422113455/http://www.notre-dame-de-rocamadour.com/