| Robotron: 2084 | |

|---|---|

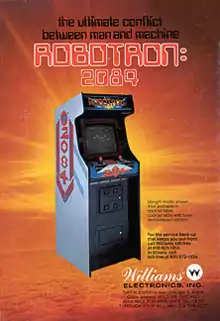

Arcade flyer | |

| Developer(s) | Vid Kidz Shadowsoft (Lynx) |

| Publisher(s) | Williams Electronics Ports Atarisoft Atari, Inc. Atari Corporation |

| Designer(s) | Eugene Jarvis Larry DeMar |

| Programmer(s) | Eugene Jarvis Larry DeMar Ports Judy Bogart (Atari 8-bit)[1] David Brown (7800)[1] Tom Griner (C64)[1] Dave Dies (Lynx)[1] |

| Platform(s) | Arcade, Apple II, Atari 8-bit, Atari 5200, Atari 7800, Atari ST, BBC Micro, Commodore 64, Lynx, IBM PC, VIC-20 |

| Release | 1982: Arcade 1983: Apple II, Atari 8-bit, 5200, C64, IBM PC, VIC-20 1985: BBC Micro 1986: Atari 7800 1987: Atari ST[2] 1991: Lynx[3] |

| Genre(s) | Multidirectional shooter |

| Mode(s) | 1-2 players, alternating turns |

Robotron: 2084 (also referred to as Robotron) is a multidirectional shooter developed by Eugene Jarvis and Larry DeMar of Vid Kidz and released in arcades by Williams Electronics in 1982. The game is set in the year 2084 in a fictional world where robots have turned against humans in a cybernetic revolt. The aim is to defeat endless waves of robots, rescue surviving humans, and earn as many points as possible.

Jarvis and DeMar drew inspiration from Nineteen Eighty-Four, Berzerk and Space Invaders for the design of Robotron: 2084. A two-joystick control scheme was implemented to provide the player with more precise controls, and enemies with different behaviors were added to make the game challenging. Jarvis and DeMar designed the game to instill panic in players by presenting them with conflicting goals and having on-screen projectiles coming from multiple directions.

Robotron: 2084 was critically and commercially successful. Praise among critics focused on the game's intense action and control scheme. Though not the first game with a twin joystick control scheme, Robotron: 2084 is cited as the game that popularized it. It was ported to numerous home systems - most of which are hampered by the lack of two joysticks - and inspired the development of other games such as Smash TV (1990). The game is frequently listed as one of Jarvis's best contributions to the video game industry.

Gameplay

Robotron is a 2D multidirectional shooter game in which the player controls the on-screen protagonist from a top-down perspective. The game is set in the year 2084 in a fictional world where robots ("Robotrons") have taken control of the world and eradicated most of the human race. The main protagonist is called "Robotron Hero" who is a super-powered genetic engineering error (or mutant) and attempts to save the last human family.[4][5][6]

The game uses a two-joystick control scheme; the left joystick controls the on-screen character's movement, while the right controls the direction the character's weapon fires. Both joysticks allow for an input direction in one of eight ways. Each level, referred to as a "wave", is a single screen populated with a large number of various enemy robots and obstacles; types range from invincible giants to robots that continually manufacture other robots that shoot the protagonist. Coming into contact with an enemy, projectile, or obstacle costs the player one life, but extra lives can be earned at certain point totals. Waves also include human family members who can be rescued to score additional points, but certain robots can either kill them or turn them into enemies. Destroying all vulnerable robots allows the player to progress to the next wave; the cycle continues until all lives are lost.[4][5][6]

Development

Robotron: 2084 features monaural sound and raster graphics on a 19-inch CRT monitor.[5] It uses a Motorola 6809 central processing unit that operates at 1MHz.[7] Sounds are generated in software, with the same routines as in other Williams games of the era. The game uses a priority scheme to determine which sounds to play on a single channel.[8] A custom blitter chip generates the on-screen objects and visual effects. It transfers memory faster than the CPU, allowing the game to simultaneously animate a large number of objects.[7][9]

The game was developed in six months by Eugene Jarvis and Larry DeMar, founders of Vid Kidz.[7] Vid Kidz served as a consulting firm that designed games for Williams Electronics (part of WMS Industries), whom Jarvis and DeMar had previously worked for.[10] The game was designed to provide excitement for players; Jarvis described the game as an "athletic experience" derived from a "physical element" in the two-joystick design. Robotron: 2084's gameplay is based on presenting the player with conflicting goals: avoid enemy attacks to survive, defeat enemies to progress, and save the family to earn points.[11] It was first inspired by Stern Electronics' 1980 arcade game Berzerk and the Commodore PET computer game Chase. Berzerk is a shooting game in which a character traverses a maze to shoot robots, and Chase is a text-based game in which players move text characters into others.[7][12]

The initial concept involved a passive main character; the object was to get robots that chased the protagonist to collide with stationary, lethal obstacles.[7][8] The game was deemed too boring compared to other action titles on the market and shooting was added to provide more excitement.[7][13] The shooting elements drew inspiration from 1978 arcade game Space Invaders (1978), which had previously inspired Defender.[14]

The dual-joystick design was developed by Jarvis, and resulted from two experiences in Jarvis's life: an automobile accident and playing Berzerk. Prior to beginning development, Jarvis injured his right hand in an accident—his hand was still in a cast when he returned to work, which prevented him from using a traditional joystick with a button. While in rehabilitation, he thought of Berzerk.[10][12] Though Jarvis enjoyed the game and similar titles, he was dissatisfied with the control scheme; Berzerk used a single joystick to move the on-screen character and a button to fire the weapon, which would shoot the same direction the character was facing.[10][13] Jarvis noticed that if the button was held down, the character would remain stationary and the joystick could be used to fire in any direction.[7][13] This method of play inspired Jarvis to add a second joystick dedicated to aiming the direction projectiles were shot.[13] Jarvis and DeMar created a prototype using a Stargate arcade system board and two Atari 2600 controllers attached to a control panel.[7][10] In retrospect, Jarvis considers the design a contradiction that blends "incredible freedom of movement" with ease of use.[8]

The developers felt a rescue theme similar to Defender—one of their previous games—was needed to complete the game, and added a human family as a method to motivate players to earn a high score.[12][13] The rescue aspect also created a situation where players had to constantly reevaluate their situation to choose the optimal action: run from enemies, shoot enemies, or rescue humans.[8][11] Inspired by George Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four, Jarvis and DeMar worked the concept of an Orwellian world developed into the plot. The two noticed, however, that 1984 was approaching, but the state of the real world did not match that of the book. They decided to set the game further in the future, the year 2084, to provide a more realistic timeframe for their version of "Big Brother". Jarvis, a science fiction fan, based the Robotrons on the idea that computers would eventually become advanced entities that helped humans in everyday life. He believed the robots would eventually realize that humans are the cause of the world's problems and revolt against them.[10]

Jarvis and DeMar playtested the game themselves, and continually tweaked the designs as the project progressed.[8] Though games at the time began to use scrolling to have larger levels, the developers chose a single screen to confine the action.[13] To instill panic in the player, the character was initially placed in the center of the game's action, and had to deal with projectiles coming from multiple directions, as opposed to previous shooting games such as Space Invaders and Galaxian, where the enemies attacked from a single direction. This made for more challenging gameplay, an aspect Jarvis took pride in.[10] Enemies were assigned to stages in different groups to create themes.[7] Early stages were designed to be relatively simple compared to later ones. The level of difficulty was designed to increase quickly so players would struggle to complete later stages. In retrospect, Jarvis attributes his and DeMar's average player skills to the game's balanced design. Though they made the game as difficult as they could, the high end of their skills ended up being a good challenge for expert players.[8] The graphics were given a simple appearance to avoid a cluttered game screen, and object designs were made distinct from each other to avoid confusion. Black was chosen as the background color to help characters stand out and reduce clutter.[13]

Enemy designs

Each enemy was designed to exhibit a unique behavior toward the character; random elements were programmed into the enemies' behaviors to make the game more interesting.[7][8] The first two designed were the simplest: Electrodes and Grunts. Electrodes are stationary objects that are lethal to the in-game characters, and Grunts are simple robots that chase the protagonist by plotting the shortest path to him.[7][13] Grunts were designed to overwhelm the player with large groups.[8] While testing the game with the new control system and the two enemies, Jarvis and DeMar were impressed by the gameplay's excitement and fun. As a result, they began steadily increasing the number of on-screen enemies to over a hundred to see if more enemies would generate more enjoyment.[7][13]

Other enemies were created to add more variety. Large, indestructible Hulks, inspired by an enemy in Berzerk, were added to kill the humans on the stage. Though they cannot be destroyed, the developers decided to have the protagonist's projectiles slow the Hulk's movement as a way to help the player. Levitating Enforcers were added as enemies that could shoot back at the main character; Jarvis and DeMar liked the idea of a floating robot and felt it would be easier to animate. A projectile algorithm was devised for Enforcers to simulate enemy artificial intelligence. The developers felt a simple algorithm of shooting directly at the protagonist would be ineffective because the character's constant motion would always result in a miss. Random elements were added to make the projectile more unpredictable; the Enforcer aims at a random location in a ten-pixel radius around the character, and random acceleration curves the trajectory. To further differentiate Enforcers, Jarvis devised the Spheroid enemy as a robot that continually generated Enforcers, rather than have them already on the screen like other enemies. Brains were conceived as robots that could capture humans and brainwash them into enemies called Progs, and also launch cruise missiles that chase the player in a random zigzag pattern, making them difficult to shoot down. DeMar devised the final enemies as a way to further increase the game's difficulty; Tanks that fire projectiles which bounce around the screen, and Quarks as a tank-producing robot.[13]

In the summer of 2012, Eugene Jarvis wrote a comprehensive evaluation of the Robotron Enemy Dynamics: the game is hard-coded with 40 waves, whereupon the game repeats wave 21 to 40 over and over until the game restarts back to the original wave 1, once the player completes wave 255. In the same year, Larry DeMar provided details on how to trigger the secret copyright message in Robotron.[15]

Ports

Atari, Inc. ported Robotron: 2084 to its own systems (the Atari 8-bit family of home computers, Atari 5200, and Atari 7800), while it released the game for the Apple II, Commodore 64, VIC-20, TI-99/4A, and IBM PC compatibles under its Atarisoft label.[16] Most early conversions did not have a dual joystick and were received less favorably by critics.[13][17][18] Atari Corporation published a Lynx port in 1991.

Reception

Williams sold approximately 19,000 arcade cabinets; mini cabinets and cocktail versions were later produced.[10][12]

In 1995, Flux magazine ranked the arcade version 52nd on their Top 100 Video Games.[19] In 1996, Next Generation listed the arcade and PlayStation versions as number 63 on their "Top 100 Games of All Time", citing the game's relentless peril.[20] In 1999, Next Generation listed Robotron as number 21 on their "Top 50 Games of All Time", commenting that the game was the "most intense interactive entertainment experience ever created".[21] Retro Gamer rated the game number two on their list of "Top 25 Arcade Games", citing its simple and addictive design.[22] In 2008, Guinness World Records listed it as the number eleven arcade game in technical, creative and cultural impact.[23]

Critics lauded Robotron: 2084's gameplay. Authors Rusel DeMaria and Johnny Wilson enjoyed the excitement created by the constant waves of robots and fear of the character dying. They called it one of the more impressive games produced from the 80s and 90s.[24][25] Author John Vince considered the reward system (saving humans) and strategic elements as positive components.[26] ACE magazine's David Upchurch commented that despite the poor graphics and basic design, the gameplay's simplicity was a strong point.[27] DeMaria and Wilson considered the control scheme a highlight which provided the player a tactical advantage.[24] Owen Linzmayer of Creative Computing Video & Arcade Games praised the freedom of movement afforded by the controls.[28] Retro Gamer described it as "one of the greatest control systems of all time".[22] In retrospect, DeMar felt players continued to play the game because the control scheme offered a high level of precision.[29]

The game received praise from industry professionals as well. Midway Games's Tony Dormanesh and Electronic Arts' Stephen Riesenberger called Robotron: 2084 their favorite arcade game.[30] David Thiel, a former Gottlieb audio engineer, referred to the game as the "pinnacle of interactive game design".[31] Jeff Peters from GearWorks Games praised the playing field as "crisp and clear", and described the strategy and dexterity required to play as a challenge to the senses. He summarized the game as "one of the best examples of game play design and execution".[30] Edge magazine ranked the game 81st on their 100 Best Video Games in 2007.[32]

Legacy

Jarvis's contributions to the game's development are often cited among his accolades.[33][34] Vince considered him one of the originators of "high-action" and "reflex-based" arcade games, citing Robotron: 2084's gameplay among other games designed by Jarvis.[26] In 2007, IGN listed Eugene Jarvis as a top game designer whose titles (Defender, Robotron 2084, and Smash TV) have influenced the video game industry.[34] GamesTM referred to the game as the pinnacle of his career.[8] Shane R. Monroe of RetroGaming Radio called Robotron "...the greatest twitch and greed game of all time".[35] The game has also inspired other titles. The 1990 arcade game Smash TV, also designed by Jarvis, features a similar design—two joysticks used to shoot numerous enemies on a single screen—as well as ideas he intended to include in sequels.[13][36] In 1991, Jeff Minter released a shareware game titled Llamatron based on Robotron: 2084's design.[37] Twenty years later, Minter released an upgraded version titled Minotron: 2112 for iOS.[38] In 2017, Soiree Games released Neckbeards: Basement Arena, which is heavily inspired by Robotron.[39] Because of its popularity, the game has been referenced in facets of popular culture: the Beastie Boys' song "The Sounds of Science" on the album Paul's Boutique, Lou Reed's song "Down at the Arcade" on his New Sensations album, and the comic strip Bob the Angry Flower.[4][40][41] Players have also competed to obtain the highest score at the game.[42]

Bill Loguidice and Matt Barton of Gamasutra commented that Robotron's success, along with Defender, illustrated that video game enthusiasts were ready for more difficult games with complex controls.[17] Though not the first to implement it,[Note 1] Robotron: 2084's use of dual joysticks popularized the design among 2D shooting games, and has since been copied by other arcade-style games.[13][22][30][43] The control scheme has appeared in several other titles produced by Midway Games:[Note 2] Inferno, Smash TV, and Total Carnage.[43] Many shooting games on Xbox Live Arcade and PlayStation Network use this dual control design.[44][45][46] The 2003 title Geometry Wars and its sequels also use a similar control scheme.[43][47] The input design was most prominent in arcade games until video games with three-dimensional (3D) graphics became popular in the late 1990s. Jarvis attributes the lack of proliferation in the home market to the absence of hardware that offered two side-by-side joysticks. Most 3D games, however, use the dual joystick scheme to control the movement of a character and a camera. Few console games, like the 2004 title Jet Li: Rise to Honor, use two joysticks for movement and attacking.[17]

From 2012 through 2019, the Church Of Robotron [48] deployed a traveling multimedia installation and performance. Participants played Robotron: 2084 while being assaulted with distracting sensory events including smoke, loud noises, vibrations, and electric shocks. Other elements included live and recorded sermons, religious pamphlets, and street preaching outside of the events. Events were at the Toorcamp[49] hacker camp, PDX Makerfaire 2019, and other venues.

Remakes and sequels

Vid Kidz developed an official sequel, Blaster, in 1983. The game is set in the same universe and takes place in 2085 in a world overrun by Robotrons.[13][50][51] Jarvis planned to develop other sequels, but the video game crash of 1983 halted most video game production for a few years.[13] Williams considered creating a proper sequel in the mid-1980s as well as a film adaptation.[52][53]

Atari Corporation and Williams announced plans to develop an update of Robotron intended for the Atari Jaguar but this project was never released.[54][55] In 1996, the company released a sequel with 3D graphics titled Robotron X for the Sony PlayStation and personal computers.

Robotron: 2084 has been included in several multi-platform compilations: the 1996 Williams Arcade's Greatest Hits, the 2000 Midway's Greatest Arcade Hits, the 2003 Midway Arcade Treasures, and the 2012 Midway Arcade Origins.[56][57][58][59] In 2000, a web-based version of Robotron: 2084, along with nine other classic arcade games, were published on Shockwave.com (a website related to Adobe Shockwave).[60] Four years later, Midway Games also launched a website featuring the Shockwave versions.[61]

In 2004, Midway Games planned to release a plug and play version of Robotron: 2084 as part of a line of TV Games, but this was never released.[62][63] Robotron: 2084 became available for download via Microsoft's Xbox Live Arcade in November 2005. This version included high-definition graphics and two-player cooperative multiplayer with one player controlling the movement and another the shooting. Scores were tracked via an online ranking system.[64] In February 2010, however, Microsoft removed it from the service citing permission issues.[65]

Robotron: 2084 is playable in the Lego Dimensions Midway Arcade level pack.[66]

See also

Notes

- ↑ The two-joystick control scheme was previously used in Taito's Gun Fight (1975) and Space Dungeon (1981) as well as Artic Electronics' Mars (1981).

- ↑ Williams Electronics purchased Midway in 1988, and later transferred its games to the Midway Games subsidiary.

References

- 1 2 3 4 Hague, James. "The Giant List of Classic Game Programmers".

- ↑ "Atari ST Robotron: 2084". Atari Mania.

- ↑ "Atari Lynx - Robotron: 2084". AtariAge.

- 1 2 3 Sellers, John (August 2001). "Robotron: 2084". Arcade Fever: The Fan's Guide to The Golden Age of Video Games. Running Press. pp. 110–111. ISBN 0-7624-0937-1.

- 1 2 3 "Robotron: 2084 Videogame by Williams (1982)". Killer List of Videogames. Retrieved 2009-02-10.

- 1 2 Cook, Brad. "Robotron: 2084 - Overview - allgame". Allgame. Retrieved 2009-02-10.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 James Hague, ed. (1997). "Eugene Jarvis". Halcyon Days: Interviews with Classic Computer and Video Games Programmers. Dadgum Games.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 GamesTM Staff (October 2005). "Robotron: 2084 Behind the Scenes". GamesTM (36): 146–149.

- ↑ Vince, John (2002). Handbook of Computer Animation. Springer Science+Business Media. p. 4. ISBN 1-85233-564-5.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Kent, Steven (2001). "The Fall". Ultimate History of Video Games. Three Rivers Press. pp. 220–222. ISBN 0-7615-3643-4.

- 1 2 Sellers, John (August 2001). "The Creator". Arcade Fever: The Fan's Guide to The Golden Age of Video Games. Running Press. pp. 52–53. ISBN 0-7624-0937-1.

- 1 2 3 4 Digital Eclipse (2003-11-18). Midway Arcade Treasures (PlayStation 2). Midway Games. Level/area: The Inside Story On Robotron 2084.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Grannell, Craig (March 2009). "The Making of Robotron: 2084". Retro Gamer. Imagine Publishing (60): 44–47.

- ↑ Grannell, Craig (July 30, 2008). "Eugene Jarvis on the reality of clones in the games industry". Revert to Saved. Retrieved 19 May 2021.

- ↑ "Larry DeMar shows Robotron secret". YouTube. Archived from the original on 2015-11-26. Retrieved 2015-08-18.

- ↑ "MobyGames Quick Search: Robotron: 2084". MobyGames. Retrieved 2009-03-17.

- 1 2 3 Loguidice, Bill; Matt Barton (2009-08-04). "The History of Robotron: 2084 - Running Away While Defending Humanoids". Gamasutra. Retrieved 2009-10-15.

- ↑ Buchanan, Levi (2008-02-27). "The Atari 5200 Buyer's Guide". IGN. Retrieved 2009-03-19.

- ↑ "Top 100 Video Games". Flux. Harris Publications (4): 30. April 1995.

- ↑ "Top 100 Games of All Time". Next Generation. No. 21. Imagine Media. September 1996. p. 48.

- ↑ "Top 50 Games of All Time". Next Generation. No. 50. Imagine Media. February 1999. p. 78.

- 1 2 3 Retro Gamer Staff (September 2008). "Top 25 Arcade Games". Retro Gamer. Imagine Publishing (54): 68.

- ↑ Craig Glenday, ed. (2008-03-11). "Top 100 Arcade Games: Top 20–6". Guinness World Records Gamer's Edition 2008. Guinness World Records. Guinness. p. 235. ISBN 978-1-904994-21-3.

- 1 2 DeMaria, Rusel; Wilson, Johnny L. (2003). High Score!: The Illustrated History of Electronic Games (2 ed.). McGraw-Hill Professional. p. 86. ISBN 0-07-223172-6.

- ↑ DeMaria, Rusel; Wilson, Johnny L. (2003). High Score!: The Illustrated History of Electronic Games (2 ed.). McGraw-Hill Professional. p. 339. ISBN 0-07-223172-6.

- 1 2 Vince, John (2002). Handbook of Computer Animation. Springer Science+Business Media. pp. 1–2. ISBN 1-85233-564-5.

- ↑ Upchurch, David (February 1992). "Robotron 2084". Advanced Computer Entertainment (53): 77.

- ↑ Linzmayer, Owen (Spring 1983). "Mastering Robotron:2084". Creative Computing Video & Arcade Games. 1 (1): 21.

- ↑ Digital Eclipse (2003-11-18). Midway Arcade Treasures (PlayStation 2). Midway Games. Level/area: Interview Clip 1 – Robotron's Controls.

- 1 2 3 Hong, Quang (2005-08-05). "Question of the Week Responses: Coin-Op Favorites?". Gamasutra. Retrieved 2022-03-25.

- ↑ Kent, Steven (2001). "The Fall". Ultimate History of Video Games. Three Rivers Press. p. 219. ISBN 0-7615-3643-4.

- ↑ EDGE presents: The 100 Best Videogames (2007). United Kingdom: Future Publishing. 16 August 2020. p. 44.

- ↑ Maragos, Nich (2005-02-17). "Eugene Jarvis To Receive IGDA Lifetime Achievement Award". Gamasutra. Retrieved 2009-05-12.

- 1 2 IGN Staff (2007-07-24). "Top 10 Tuesday: Game Designers". IGN. Archived from the original on 2012-02-14. Retrieved 2009-03-16.

- ↑ Passenger Seat Radio, Episode 2008-08-07 3:24

- ↑ Rollings, Andrew; Adams, Ernest (2003). Andrew Rollings and Ernest Adams on Game Design. New Riders. p. 283. ISBN 1-59273-001-9.

- ↑ "Llamasoft – 16 Bit". Llamasoft. Retrieved 2009-03-16.

- ↑ Minter, Jeff (2011-02-24). "I have been a busy ox. Again". Llamasoft. Retrieved 2011-03-04.

- ↑ "Soiree Games". Soiree.info. Retrieved 2019-05-25.

- ↑ Lou Reed (Singer) (April 1984). Album: New Sensations Song: Down at the Arcade. RCA.

- ↑ "Robotron 2083". Bob the Angry Flower. Stephen Notley. 2006-03-10. Retrieved 2009-03-16.

- ↑ "Robotron: 2084 High Score Rankings". Twin Galaxies. Retrieved 2009-07-28.

- 1 2 3 Harris, John (2007-12-06). "Game Design Essentials: 20 Unusual Control Schemes". Gamasutra. Retrieved 2009-05-12.

- ↑ Donahoe, Michael (November 2007). "Online Scene: Robocopied". Electronic Gaming Monthly. No. 221. Ziff Davis. p. 50.

- ↑ Retro Gamer Staff (April 2008). "Retro Rated: Omega Five". Retro Gamer. Imagine Publishing (49): 88.

- ↑ Retro Gamer Staff (October 2008). "Retro Rated: Commando 3". Retro Gamer. Imagine Publishing (55): 89.

- ↑ Gamasutra Staff (2008-12-23). "Gamasutra's Best Of 2008: Top 10 Games Of The Year". Gamasutra. Retrieved 2009-05-12.

- ↑ "CHURCH OF ROBOTRON". Retrieved 2022-12-13.

- ↑ Evenchick, Eric (2012-08-20). "Toorcamp: The Church Of Robotron". Hackaday. Retrieved 2022-12-13.

- ↑ "Blaster Videogame by Williams (1983)". Killer List of Videogames. Retrieved 2009-03-17.

- ↑ Green, Earl. "Blaster - Overview - allgame". Allgame. Retrieved 2009-03-17.

- ↑ Digital Eclipse (2003-11-18). Midway Arcade Treasures (PlayStation 2). Midway Games. Level/area: Joust 2 Interview Clip #2.

- ↑ Digital Eclipse (2003-11-18). Midway Arcade Treasures (PlayStation 2). Midway Games. Level/area: The Inside Story On Joust.

- ↑ Dayes, Albert (October 9, 1994). "Digital Briefs - Industry News - Atari News - Atari & Williams Join Forces". Atari Explorer Online. Vol. 3, no. 12. Subspace Publishers. Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2019-04-03.

- ↑ "ProNews: Williams Makes Jaguar, Ultra 64 Plans". GamePro. No. 66. IDG. January 1995. p. 85. Archived from the original on 2018-07-28. Retrieved 2018-07-28.

- ↑ Weiss, Brett Alan. "Williams Arcade's Greatest Hits - Overview - allgame". Allgame. Archived from the original on 2009-07-01. Retrieved 2009-03-18.

- ↑ All Game Staff. "Midway's Greatest Arcade Hits: Vol. 1 - Overview - allgame". Allgame. Retrieved 2009-03-18.

- ↑ Harris, Craig (2003-08-11). "Midway Arcade Treasures". IGN. Retrieved 2009-02-10.

- ↑ "Midway Arcade Origins Review". Ign.com. 14 November 2012.

- ↑ Parker, Sam (2000-05-05). "Midway Coming Back At You". GameSpot. Archived from the original on 2009-08-27. Retrieved 2009-03-20.

- ↑ Kohler, Chris (2004-09-24). "Midway Arcade Treasures Web site goes live". GameSpot. Archived from the original on 2013-01-02. Retrieved 2009-03-17.

- ↑ Harris, Craig (2004-02-17). "Midway's TV Games". IGN. Retrieved 2009-02-10.

- ↑ Vavasour, Jeff (2009-02-16). "Jeff Vavasour's Video And Computer Game Page". Retrieved 2009-05-01.

- ↑ Gerstmann, Jeff (2005-12-20). "Robotron: 2084 Review". GameSpot. Archived from the original on 2006-11-30. Retrieved 2009-03-16.

- ↑ Sinclair, Brendan (2010-02-17). "Midway XBLA games pulled". GameSpot. Retrieved 2011-02-15.

- ↑ Crecente, Brian (March 24, 2016). "Lego Dimensions delivers a playable video game museum with Midway Arcade". Polygon. Vox Media. Archived from the original on March 24, 2016.

External links

- The arcade version of Robotron: 2084 can be played for free in the browser at the Internet Archive

- Robotron2084 Guidebook

- Robotron: 2084 on Coinop.org

- Time Extend: Robotron 2084 at Edge-Online

- Eurogamer Retrospective: Robotron: 2084

- Robotron: 2084 information on Arcade-History

- Williams hardware/software technical information

- Robotron: 2084 at MobyGames