| Rickettsia rickettsii | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Bacteria |

| Phylum: | Pseudomonadota |

| Class: | Alphaproteobacteria |

| Order: | Rickettsiales |

| Family: | Rickettsiaceae |

| Genus: | Rickettsia |

| Species group: | Spotted fever group |

| Species: | R. rickettsii |

| Binomial name | |

| Rickettsia rickettsii Brumpt, 1922 | |

Rickettsia rickettsii is a Gram-negative, intracellular, coccobacillus bacterium that was first discovered in 1902.[1] R. rickettsii is the causative agent of Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever and is transferred to its host via a tick bite. It is one of the most pathogenic Rickettsia species[2] and affects a large majority of the Western Hemisphere, most commonly the Americas.[3]

Life cycle

The most common hosts for the R. rickettsii bacteria are ticks.[4] Ticks that carry R. rickettsia fall into the family of Ixodidae ticks, also known as "hard-bodied" ticks.[5] Ticks are vectors, reservoirs, and amplifiers of this disease.[4]

There are currently three known tick species that commonly carry R. rickettsii. The American Dog Tick (Dermacentor variabilis), mainly found in the eastern United States, is the most common vector for R. rickettsii. The Rocky Mountain Wood Tick (Dermacentor andersoni), found in the Rocky Mountain States, and the Brown Dog Tick (Rhipicephalus sanguine), found in select areas of the southern United States, are also known vectors of the pathogen.[5][6]

Ticks can contract R. rickettsii by many means. First, an uninfected tick can become infected when feeding on the blood of an infected vertebrate host; such as a rabbit, during the larval or nymph stages, this mode of transmission is called transstadial transmission.[7] Once a tick becomes infected with this pathogen, they are infected for life. Both the American Dog Tick and the Rocky Mountain Wood Tick serve as long-term reservoirs for Rickettsia rickettsii, in which the organism resides in the tick posterior diverticula of the midgut, the small intestine and the ovaries.[7] In addition, an infected male tick can transmit the organism to an uninfected female during mating. Once infected, the female tick can transmit the infection to her offspring, in a process known as transovarian passage.[8]

Transmission in mammals

Due to its confinement in the midgut and small intestine, Rickettsia rickettsii can be transmitted to mammals, including humans.

Transmission can occur in multiple ways. One way to contract the infection is through contact with an infected host's feces. If an infected host's feces come into contact with an open skin barrier, it is possible for the disease to be transmitted. An uninfected host can become infected when eating food that contains the feces of the infected vector.[9] Another way of contraction is by the bite of an infected tick. After getting bitten by an infected tick, R. rickettsiae are transmitted to the bloodstream by tick salivary secretions.[9]

Having multiple modes of transmission ensures the persistence of R. rickettsii in a population. Additionally, having multiple modes of transmission helps the disease adapt better to new environments and prevents it from becoming eradicated. R. rickettsii has evolved a number of strategic mechanisms, or virulence factors, that allow it to invade the host immune system and successfully infect its host.[10]

Genome and phenotypes

R. rickettsii is an obligate intracellular alpha proteobacterium that belongs to the Rickettsiacea family.[11] It has a genome that consists of about 1.27 Mbp with ~1,350 predicted genes,[12] which is smaller compared to most other bacteria. It is maintained in its tick host by transovarial transmission.[11] The multiplication of R. rickettsii is by binary fission inside the cytosol.[13]

There are many strains of R. rickettsii that have been discovered with key characteristics that differentiate them. R. rickettsii Sheila Smith is a virulent strain that causes spotted fever. Other strains of R. rickettsii, such as R. rickettsii Iowa, have a genomic structure consistent with an avirulent phenotype.[14] A key feature allowing for differentiation is the rickettsial outer membrane protein, rOmpA and rOmpB [12] which contributes to the identification of R. rickettsii strains as virulent. The detection of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) are used to differentiable these strains.[12]

Clinical manifestations

Virulence

While humans are hosts for R. rickettsii they do not contribute to rickettsial transmission, rather the pathogen is maintained through its vector, ticks.[10] R. rickettsii invades the endothelial cells that line the blood vessels in the host's body. The pathogen causes changes in the host cell cytoskeleton that induces phagocytosis and R. rickettsii replicates further and infects other cells in the host's body.[16] R. rickettsii's survival in immune system cells increases the pathogen's virulence in mammalian hosts.

Actin-Based Motility (ABM) is a virulence factor that allows for the pathogen to evade the host's immune cells and spread to neighboring cells. It is suggested that the Sca2 gene, which is an actin-polymerizing determinant, is a distinguishing factor for the Rickettsia family, as R. rickettsii mutants with a Sca2 transposon avoided autophagic processes. This leads to an increase in disease manifestation for the host.[10]

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention states that the diagnosis of Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever must be made based on the clinical signs and symptoms of the patient and then later be confirmed using specialized laboratory tests. However, the diagnosis of Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever is often misdiagnosed due to its non-specific onset. The majority of infections from R. rickettsii occur during the warmer months between April and September. Symptoms can take 1–2 days to 2 weeks to present themselves within the host.[17] The diagnosis of RMSF is easier when there is a known history of a tick bite or if the rash is already apparent in the affected individual.[18] If not treated properly, the illness may become serious, leading to hospitalization and possible fatality.[19]

Signs and symptoms

During the initial stages of the disease, the infected person may experience headaches, muscle aches, chills, and high fever. Other early symptoms may include nausea, vomiting, loss of appetite, and conjunctival injection (red eyes). Most people infected by R. rickettsii develop a spotted rash, that begins to appear 2 to 4 days after the individual develops a fever. If left untreated, more severe symptoms may develop; these symptoms may include insomnia, compromised mental ability, coma, and damage to the heart, kidneys, liver, lungs, or additional organs.[20][17]

The classic Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever rash occurs in about 90% of patients and develops 2 to 5 days after the onset of fever. The rash can differ greatly in appearance along the progress of the R. rickettsii infection.[20] It is not itchy and starts out as flat pink macules located on the affected individual's hands, feet, arms, and legs.[18] During the course of the disease, the rash may form petechiae and take on a more darkened reddish purple spotted appearance, signifying severe disease.[21]

Severe infections

Patients with severe infections may require hospitalization. The more severe symptoms occur later in response to of thrombosis (blood clotting) caused by R. rickettsii targeting endothelial cells in vascular tissue.[17][22] They may become hyponatremic, experience elevated liver enzymes, and other more pronounced symptoms. It is not uncommon for severe cases to involve respiratory system, central nervous system, gastrointestinal system, or renal system complications. This disease is worst for elderly patients, males, African Americans, alcoholics, and patients with G6PD deficiency. The mortality rate for RMSF is 3 to 5 percent in treated cases, but 13 to 25 in untreated cases.[18] Deaths usually are caused by heart and kidney failure.[8]

History

Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever (RMSF) first emerged in the Idaho Valley in 1896 after being recognized by Major Marshall H. Wood.[1] At the time of discovery, not much information was known about the disease. It was originally called "Black Measles" due to the infected area turning black during the late stages of the disease.[23] The first clinical description of Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever was reported in Snake River Valley in 1899 by Edward E. Maxey.[24] At the time, 69% of individuals diagnosed with RMSF died.[1]

Howard Ricketts (1871–1910), an associate professor of pathology at the University of Chicago in 1902, was the first to identify and study R. rickettsii.[1] His research entailed interviewing victims of the disease as well as collecting infected animals to study. He was known to inject himself with pathogens to measure their effects. His research provided more information on the organism's vector and route of transmission.[1]

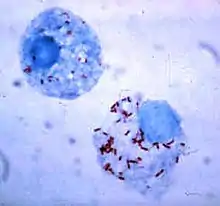

Simeon Burt Wolbach is credited for the first detailed description of the pathogenic agent that causes R. rickettsii in 1919. He described RMSF using the process of Giemsa stain.[1] He recognized the pathogenic agent as an intracellular bacterium that was seen most frequently in endothelial cells.[3]

The once lethal infection has become curable due to the research done in recent years. The fatality rate has dropped to between 5 and 10% since the 1940s.[25] The pathogenic agent, R. rickettsii, has been found on every continent, except Antarctica; however, Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever occurs mostly in North, Central, and South America.[3] This prevalence is due to R. rickettsi thriving in warm, damp environments.[4]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever (RMSF): Background, Etiology and Pathophysiology, Epidemiology". 2023-06-13.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Hackstadt, Ted. "Biology of Rickettsia".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - 1 2 3 Vail, Michael R. Conover, Rosanna M. (2014), "Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever and Other Spotted Fevers", Human Diseases from Wildlife, CRC Press, pp. 252–265, doi:10.1201/b17428-18, ISBN 978-0-429-10009-3, retrieved 2023-10-31

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - 1 2 3 Parola P, Paddock CD, Raoult D (October 2005). "Tick-borne rickettsioses around the world: emerging diseases challenging old concepts". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 18 (4): 719–756. doi:10.1128/CMR.18.4.719-756.2005. PMC 1265907. PMID 16223955.

- 1 2 Parola P, Davoust B, Raoult D (2005-06-01). "Tick- and flea-borne rickettsial emerging zoonoses". Veterinary Research. 36 (3): 469–492. doi:10.1051/vetres:2005004. PMID 15845235.

- ↑ Jay, Riley; Armstrong, Paige (2020-04-01). "Clinical characteristics of Rocky Mountain spotted fever in the United States: A literature review". Journal of Vector Borne Diseases. 57 (2): 114–120. doi:10.4103/0972-9062.310863. PMID 34290155.

- 1 2 Ravindran R, Hembram PK, Kumar GS, Kumar KG, Deepa CK, Varghese A (March 2023). "Transovarial transmission of pathogenic protozoa and rickettsial organisms in ticks". Parasitology Research. 122 (3): 691–704. doi:10.1007/s00436-023-07792-9. PMC 9936132. PMID 36797442.

- 1 2 Tortora GJ, Funke BR, Case CL (2013). Microbiology: An Introduction. United States of America: Pearson Education, Inc. pp. 661–662. ISBN 978-0-321-73360-3.

- 1 2 Kim HK (September 2022). "Rickettsia-Host-Tick Interactions: Knowledge Advances and Gaps". Infection and Immunity. 90 (9): e0062121. doi:10.1128/iai.00621-21. PMC 9476906. PMID 35993770.

- 1 2 3 Pathogenicity and virulence of Rickettsia. Virulence. December 2022;13(1):1752–1771. doi:10.1080/21505594.2022.2132047. PMID 36208040.

- 1 2 Hackstadt T. "Biology of Rickettsia".

- 1 2 3 Clark TR, Noriea NF, Bublitz DC, Ellison DW, Martens C, Lutter EI, Hackstadt T (April 2015). Morrison RP (ed.). "Comparative genome sequencing of Rickettsia rickettsii strains that differ in virulence". Infection and Immunity. 83 (4): 1568–1576. doi:10.1128/IAI.03140-14. PMC 4363411. PMID 25644009.

- ↑ "Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever (RMSF): Background, Etiology and Pathophysiology, Epidemiology". 2023-06-13.

- ↑ Ellison DW, Clark TR, Sturdevant DE, Virtaneva K, Porcella SF, Hackstadt T (February 2008). "Genomic comparison of virulent Rickettsia rickettsii Sheila Smith and avirulent Rickettsia rickettsii Iowa". Infection and Immunity. 76 (2): 542–550. doi:10.1128/IAI.00952-07. PMC 2223442. PMID 18025092.

- ↑ "Ixodes species". Learn About Parasites. Western College of Veterinary Medicine. Retrieved 2023-10-26.

- ↑ Sahni, Abha; Fang, Rong; Sahni, Sanjeev; Walker, David H. (2019-01-24). "Pathogenesis of Rickettsial Diseases: Pathogenic and Immune Mechanisms of an Endotheliotropic Infection". Annual Review of Pathology. 14: 127–152. doi:10.1146/annurev-pathmechdis-012418-012800. ISSN 1553-4006. PMC 6505701. PMID 30148688.

- 1 2 3 "Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever". Red Book. American Academy of Pediatrics. 2018-05-01. pp. 697–700. doi:10.1542/9781610021470-part03-rocky_mountain. ISBN 978-1-61002-147-0. S2CID 232564979. Retrieved 2023-10-21.

- 1 2 3 Palatucci OA, Marangoni BA. "Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever". SpringerReference. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag. Archived from the original on 6 May 2020. Retrieved 2023-10-21.

- ↑ "Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever". www.hopkinsmedicine.org. 2019-11-19. Retrieved 2023-11-03.

- 1 2 CDC (2019-05-07). "Rocky Mountain spotted fever home". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 2023-10-21.

- ↑ CDC (2019-02-19). "Signs and symptoms of RMSF for healthcare providers". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 2023-11-03.

- ↑ Kristof MN, Allen PE, Yutzy LD, Thibodaux B, Paddock CD, Martinez JJ (February 2021). "Significant Growth by Rickettsia Species within Human Macrophage-Like Cells Is a Phenotype Correlated with the Ability to Cause Disease in Mammals". Pathogens. 10 (2): 228. doi:10.3390/pathogens10020228. PMC 7934685. PMID 33669499.

- ↑ "Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever". www.niaid.nih.gov. 2014-07-08. Retrieved 2023-10-31.

- ↑ Xiao, Yongli; Beare, Paul A.; Best, Sonja M.; Morens, David M.; Bloom, Marshall E.; Taubenberger, Jeffery K. (2023-03-22). "Genetic sequencing of a 1944 Rocky Mountain spotted fever vaccine". Scientific Reports. 13 (1): 4687. Bibcode:2023NatSR..13.4687X. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-31894-0. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 10031714. PMID 36949107.

- ↑ CDC (2022-08-15). "Epidemiology and statistics of spotted fever rickettsioses". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 2023-10-31.

Further reading

- Dumbler SJ, Walker DH (2006). "Order II. Rickettsiales Gieszczkiewicz 1939..". In Garrity G, Brenner DJ, Staley JT, Krieg NR, Boone DR, Vos PD, et al. (eds.). Bergey's Manual® of Systematic Bacteriology: Volume Two: The Proteobacteria (Part C). Springer. pp. 96–. ISBN 978-0-387-29298-4.

- Weiss K (1988). "The Role of Rickettsioses in History". In Walker DH (ed.). Biology of Rickettsial Diseases. CRC Press. pp. 2–14. ISBN 978-0-8493-4382-7.

- Weiss E (1988). "History of Rickettsiology". Biology of Rickettsial Diseases. pp. 15–32.

- Wilson BA, Salyers AA, Whitt DD, Winkler ME (2011). Bacterial Pathogenesis: A Molecular Approach (3rd ed.). Amer Society for Microbiology. ISBN 978-1-55581-418-2.

- Todar K (2008–2012). "Rickettsial Diseases, including Typhus and Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever". Todar's Online Textbook of Bacteriology.

External links

- "Rickettsia rickettsii genomes and related information". PATRIC, Bioinformatics Resource Center. NIAID.

- "Rickettsia rickettsii: The Cause of Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever". Multiple Organisms: Organismal Biology. University of Wisconsin-La Crosse. 2007.

- "Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever (RMSF)". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 21 November 2013.