René Gagnon | |

|---|---|

Private René Gagnon, USMC in 1943 | |

| Born | March 7, 1925 Manchester, New Hampshire, U.S. |

| Died | October 12, 1979 (aged 54) Manchester, New Hampshire, U.S. |

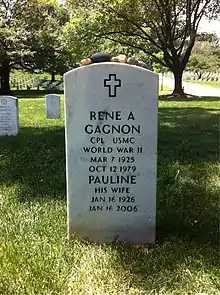

| Buried | Originally on Mount Cavalry Cemetery Currently on Arlington National Cemetery |

| Allegiance | United States |

| Service/ | United States Marine Corps |

| Years of service | 1943–1946 |

| Rank | Corporal |

| Unit | 2nd Battalion 28th Marines 5th Marine Division |

| Battles/wars | World War II |

| Awards | World War II Victory Medal |

René Arthur Gagnon (March 7, 1925 – October 12, 1979) was a United States Marine Corps corporal who participated in the Battle of Iwo Jima during World War II.

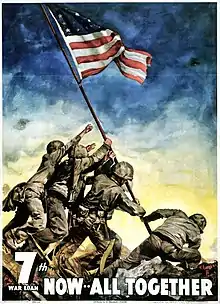

Gagnon was generally known as being one of the Marines who raised the second U.S. flag on Mount Suribachi on February 23, 1945, as depicted in the iconic photograph Raising the Flag on Iwo Jima by photographer Joe Rosenthal. On October 16, 2019, the Marine Corps announced publicly (after an investigation) that Corporal Harold Keller, not Gagnon, was in Rosenthal's photo.[1] Gagnon was one of three men who were originally identified incorrectly as flag-raisers in the photograph (the others being Hank Hansen and John Bradley).[2]

The first flag that had been raised was deemed too small. Later that day, Gagnon, a runner in the 5th Marine Division, was given a larger flag to take up the mountain. A photo of the second flag-raising became famous and was widely reproduced. After the battle, Gagnon and two other men who were identified as surviving second flag-raisers were reassigned to help raise funds for the Seventh War Loan drive.

The Marine Corps War Memorial in Arlington, Virginia, is modeled after Rosenthal's photograph of six Marines raising the second flag on Iwo Jima.

Early years

Gagnon was born March 7, 1925, in Manchester, New Hampshire, the only child of French Canadian immigrants from Disraeli, Quebec, Henri Gagnon and Irène Marcotte. He grew up without a father. His parents separated when he was an infant, though they never divorced. When he was old enough, he worked alongside his mother at a local shoe factory. He also worked as a bicycle messenger boy for the local Western Union.

U.S. Marine Corps

World War II

Gagnon was inducted into the United States Marine Corps Reserve on May 6, 1943.[3] He was sent to the Marine Corps Recruit Depot Parris Island, South Carolina. On July 16, he was promoted to private first class.[3] He was transferred to the Marine Guard Company at Charleston Navy Yard in South Carolina and remained there for eight months. On April 4, 1944, he joined the Military Police Company of the 5th Marine Division at Camp Pendleton, California. On April 8, 1944, he was transferred to the 2nd Battalion, 28th Marine Regiment, 5th Marine Division.[3] In September, the 5th division left Camp Pendleton for further training at Camp Tarawa, Hawaii. The 5th Division trained there to prepare for the assault on Iwo Jima by three Marine divisions of the V Amphibious Corps (code named "Operation Detachment").

Battle of Iwo Jima

On February 19, 1945, Pfc. Gagnon landed on the southeast side of Iwo Jima with E Company, 2nd Battalion, 28th Marines, on "Green Beach 1", which was the closest landing beach to Mount Suribachi on the southern end of the island. On February 23, Pfc. Gagnon who was the battalion runner (messenger) for Easy Company,[4] incorrectly became a part of what was most likely the most celebrated American flag raising in U.S. history.

First flag-raising

On the morning of February 23, Lieutenant Colonel Chandler W. Johnson commander of the Second Battalion, 28th Marines, ordered E Company's commander Captain Dave Severance to send a platoon-sized patrol from his company up Mount Suribachi to lay siege to and occupy the crest. The remainder of Third platoon, other Marines from the battalion, and two Navy corpsmen, formed a 40-man patrol. If they made it to the top, First Lieutenant Harold G. Schrier, E Company's executive officer who was selected by the 28th Marines commander to lead the patrol, was to raise the Second Battalion's flag on top to signal that the mountaintop was secure. On orders from Lt. Col Johnson, First Lieutenant George G. Wells the battalion adjutant handed Lt. Schrier the flag just before the patrol left the base of Mount Suribachi at about 8:30 a.m. Once Lt. Schrier was on top with his men after some occasional sniper fire and a brief firefight at the rim, he and two other Marines attached the flag to a length of Japanese iron water pipe that was found. Lt. Schrier, Platoon Sgt. Ernest Thomas, Sergeant Henry Hansen,[5] and Corporal Charles Lindberg, raised the flag at approximately 10:30 a.m.[6] Seeing the raising of the national colors immediately caused loud cheers from the Marines, sailors, and Coast Guardsmen on the south end beaches of Iwo Jima and from the men on the ships near the beach. Third Platoon corpsman John Bradley pitched in with Private Phil Ward to help make the flagstaff stay vertical. The men at, around, and holding the flagstaff which included Lt. Schrier's radio operator, Private First Class Raymond Jacobs (assigned to patrol from F Company), were photographed several times by Staff Sergeant Lou Lowery, a photographer with Leatherneck magazine who accompanied the patrol up the mountain. Platoon Sgt. Thomas was killed on Iwo Jima on March 3 and Sgt. Hansen was killed on March 1.

Second flag-raising

Approximately two hours after the first flag was raised, Lt. Col. Johnson decided that a larger U.S. flag should replace it so the flag could be more visible on the other side of the mountain where thousands of Marines were fighting to take the island. Sgt. Michael Strank, a rifle squad leader of Second Platoon, E Company, was ordered by Captain Severance to take three of his Marines up to the top of Mount Suribachi and raise a second flag which was obtained from one of the ships docked on shore. Sgt. Strank selected Cpl. Harlon Block, Pfc. Ira Hayes, and Pfc. Franklin Sousley. Capt. Severance also ordered Pfc. Gagnon, E Company's runner, to take radio batteries and the replacement flag up the mountain and return with the battalion's flag.

Once the four Marines and Pfc. Gagnon were on top, a Japanese pipe was found by Pfc. Hayes and Pfc. Sousley and taken near the first flag position where Sgt. Strank and Cpl. Block were preparing the ground where it would be raised from. The replacement flag was attached to the pipe and, as Sgt. Strank and his three Marines were about to raise the flagstaff, he yelled out to two nearby Marines to help them raise the flagstaff. Under Lt. Schrier's orders, Sgt. Strank, Cpl. Block (incorrectly identified as Sgt. Hansen until January 1947), Pfc. Hayes, Pfc. Sousley, Private First Class Harold Schultz,[7] and Private First Class Harold Keller[1] raised the flag as the first flagstaff was lowered by Pfc. Gagnon and three Marines at approximately 1 p.m.[2] Pfc. Schultz and Pfc. Keller were both members of Lt. Schrier's patrol. Afterwards, rocks were added to the bottom of the flagstaff which was then stabilized by three guy-ropes. The second raising was immortalized by the black-and-white photograph of the flag raising by Joe Rosenthal of the Associated Press. Marine photographer Sergeant Bill Genaust also filmed the second flag raising in color.[8] Lt. Col. Johnson was killed on Iwo Jima on March 2 and Sgt. Genaust was killed on March 4. Sgt. Strank and Cpl Block were killed on March 1 and Pfc. Sousley was killed on March 21.

On March 14, 1945, a third American flag was officially raised up a flagpole by two Marines during a ceremony at the V Amphibious Corps command post located on the other side of Mount Suribachi; the second flag on Mount Suribachi was taken down at the same time and delivered to the Second Battalion's headquarters. The battle of Iwo Jima was officially over on March 26 and a service was held at the 5th Marine Division cemetery. On March 27, the 2nd Battalion, 28th Marines and Pfc. Gagnon left Iwo Jima for Hawaii, and both of the U.S. flags that were flown on Mount Suribachi were sent to Marine Headquarters in Washington, D.C.

In 1991, former Marine Lt. George Greeley Wells, who was the Second Battalion, 28th Marines, adjutant in charge of carrying the American flag(s) for the battalion on Iwo Jima, stated in The New York Times that he was ordered by the battalion commander on February 23, 1945, to get a large replacement flag for the one on top of Mount Suribachi, and that he (Wells) ordered Pfc. Gagnon, the battalion's runner for E Company, to get a larger flag from a ship on shore—possibly the USS Duval County (LST-758).[9] Wells stated that this flag was the one taken up Mount Suribachi by Pfc. Gagnon to be given to Lt. Schrier, with a message for Lt. Schrier to raise this flag and return the smaller flag raised earlier on Mount Suribachi back to Gagnon. Wells also stated, that he had handed the original flag to Lt. Schrier that he (Lt. Schrier) took up Mount Suribachi, and when this flag was returned to him (Wells) by Pfc. Gagnon, he secured the flag until it was delivered to Marine Headquarters in Washington, D.C., after the Second Battalion returned to Hawaii from Iwo Jima.[10][11][12][13]

Government war bond tour

In February or March 1945, President Roosevelt ordered that the flag raisers in Joe Rosenthal's photograph be sent immediately after the battle to Washington, D.C., to appear as a public morale factor. Pfc. Gagnon had returned with his unit to Camp Tarawa in Hawaii when he was ordered on April 3 to report to Marine Corps headquarters in Washington, D.C. He arrived on April 7, and was questioned by a lieutenant colonel at the Marine Corps public information office concerning the identities of those in the photograph (Rosenthal did not take names). On April 8, the Marine Corps gave a press release of the names of the six flag raisers in the Rosenthal photo given by Gagnon: Marines Michael Strank (KIA), Henry Hansen (KIA), Franklin Sousley (KIA), Ira Hayes, Navy corpsman John Bradley, and himself. After Gagnon gave the names of the flag raisers, Bradley and Hayes were ordered to report to Marine Corps headquarters; after the war, the Marine Corps determined that Hansen (1947), Bradley (2016), and Gagnon (2019) were not second flag-raisers.[2]

After President Roosevelt unexpectedly died on April 12, Vice President Harry S. Truman was sworn in as president the same day. Bradley was recovering from his wounds from Iwo Jima at Oakland Naval Hospital in Oakland, California, and was transferred to Bethesda Naval Hospital in Bethesda, Maryland, where he was shown Rosenthal's flag-raising photograph and was told he was in it.[14] He arrived in Washington, D.C., on crutches on or about April 19. Hayes arrived from Hawaii on April 19. Both men were questioned separately by the same Marine officer that Gagnon met with concerning the identities of the six flag-raisers in the Rosenthal photograph. Bradley agreed with all six names of the flag raisers in the photo given by Gagnon including his own. Hayes agreed with all the names too including his own except he said the man identified as Sgt. Hansen at the base of the flagstaff in the photo was really Cpl. Harlon Block. The Marine interviewer then told Hayes that a list of the names of the six flag-raisers in the photo were already released publicly and besides Block and Hansen were both killed in action (during the Marine Corps investigation in 1946, the lieutenant colonel denied Hayes ever mentioned Block's name to him).[2] After the interview, it was requested that Pfc. Gagnon, Pfc. Hayes, and Bradley participate in the Seventh War Loan drive. On April 20, Gagnon, Hayes, and Bradley met President Truman at the White House and each showed him their positions in the flag-raising poster that was on display there for the coming bond tour that they would participate in. A press conference was also held that day and Gagnon, Hayes, and Bradley were questioned about the flag-raising. The three were assigned to temporary duty with the Finance Division, U.S. Treasury Department.[3]

On May 9, the bond tour started with a flag-raising ceremony at the nation's capitol by Pfc. Gagnon, Pfc. Hayes, and PhM2c. Bradley, using the same flag that had been raised on Mount Suribachi. The tour began on May 11 in New York City. On May 24, Pfc. Hayes was ordered to report to the 28th Marines in Hawaii.[15] Pfc. Hayes left Washington by plane on May 25 and arrived at Hilo, Hawaii on May 29 and rejoined E Company at Camp Tawara. Pfc. Gagnon and PhM2c. Bradley finished the tour in Washington, D.C., on July 4. The bond tour was held in 33 American cities that raised over $26 billion to help pay for and win the war.[16]

On July 5, Gagnon was ordered to San Diego for further transfer overseas. On July 7, he got married in Baltimore, Maryland, to Pauline Georgette Harnois of Hooksett, New Hampshire.[3] By September, he was deployed overseas with the 80th Replacement Draft. On November 7, he arrived at Tsingtao, China, where he joined E Company, 2nd Battalion, 29th Marines, 6th Marine Division.[3] He later served with the 3rd Battalion, 29th Marines. In March 1946, he had been on duty with the U.S. occupation forces in China for about five months before he boarded a ship at Tsingtao at the end of the month for San Diego. Gagnon arrived in San Diego on April 20. He was promoted to corporal and was honorably discharged at Camp Pendleton, California, on April 27.[3]

Marine Corps War Memorial

The Marine Corps War Memorial in Arlington, Virginia, which was inspired by Rosenthal's photograph of the second flag-raising on Mount Suribachi, was dedicated on November 10, 1954.[17] Gagnon was depicted as the second figure from the bottom of the flagstaff with the 32-foot (9.8 M) bronze figures of the other five flag-raisers depicted on the monument until a Marine Corps investigation determined in October 2019 that he was not a flag raiser;[18] Gagnon had personally posed for the sculptor.

During the dedication, President Dwight D. Eisenhower sat upfront with Vice President Richard Nixon, Secretary of Defense Charles E. Wilson, Deputy Secretary of Defense Robert Anderson, and General Lemuel C. Shepherd, the 20th Commandant of the Marine Corps.[19] Ira Hayes, one of the three surviving flag raisers (the other two were Harold Schultz and Harold Keller) depicted on the monument was also seated upfront with Rene Gagnon, John Bradley (incorrectly identified as a flag raiser until June 2016),[7] Mrs. Martha Strank, Mrs. Ada Belle Block, and Mrs. Goldie Price (mother of Franklin Sousley).[20][7] Those giving remarks at the dedication included Robert Anderson, Chairman of Day; Colonel J.W. Moreau, U.S. Marine Corps (Retired), President, Marine Corps War Memorial Foundation; General Shepherd, who presented the memorial to the American people; Felix de Weldon, sculptor; and Richard Nixon, who gave the dedication address.[21][19] The Memorial was turned over to the National Park Service in 1955. Inscribed on the memorial are the following words:

- In Honor And Memory Of The Men of The United States Marine Corps Who Have Given Their Lives To Their Country Since 10 November 1775

Later years and death

Return to Iwo Jima

On February 19, 1965, while working as an airline sales representative for Delta Air Lines, Gagnon visited Mount Suribachi with his wife and son.[22][23]

René Gagnon, Jr. commented in 2014 that his father René Gagnon, Sr. opened a travel agency and did accounting work, and in his last job, he had worked as head of maintenance at an apartment complex in Manchester, where he suffered a heart attack in the boiler room.[24] According to the book Flags of Our Fathers (2000), in his later years Gagnon only participated in events that were at his wife's urging, events praising the U.S. flag raising on Iwo Jima. She enjoyed the limelight, whereas he, by that time, no longer did.

At the age of 53, he bitterly inventoried his lost "connections" — the jobs promised him by government people when he had been at the height of his fame, jobs that never materialized. "I'm pretty well known in Manchester," he told a reporter. "When someone who doesn't know me is introduced to me, they say 'That was you in The Photograph?' What the hell are you doing working here? If I were you, I'd have a good job and lots of money.'"[25]

Death

Gagnon died on October 12, 1979, at age 54, in Manchester, New Hampshire.[26] He resided in nearby Hooksett, and was survived by wife Pauline Gagnon (1926–2006) and son René Gagnon, Jr. He was buried at Mount Calvary Cemetery in Manchester. At the request of his widow, a government waiver was granted on April 16, 1981, and his remains were re-interred in Section 51, Grave 543 of Arlington National Cemetery on July 7. Inscribed on the back of his Arlington headstone are the words:

For God and his country he raised our flag in battle

And showed a measure of his pride

at a place called Iwo Jima

Where courage never died[27]

Military awards

Gagnon's military awards include the following:

Public honors

- Rene Gagnon monument (1995), Victory Park, Manchester, New Hampshire (has quote by Gagnon: "Do not glorify war. There's nothing glorious about it.")[28]

- Wright Museum of WWII History, Rene Gagnon exhibit, Wolfeboro, New Hampshire.[29][30] which has not been removed yet despite of the revelation that he was not the flag raiser.

Portrayal in films

Gagnon appeared in two films about the Battle of Iwo Jima: To the Shores of Iwo Jima (a government documentary which simply showed the color footage of the U.S. flag raising) and Sands of Iwo Jima (1949). He was also part of a Rose Bowl halftime show.

- Sands of Iwo Jima (1949), Gagnon played himself, raising the flag in the movie with John Bradley and Ira Hayes.

- The Outsider (1961), Gagnon was played by Ray Daley.

- Flags of Our Fathers (2006), Gagnon was played by Jesse Bradford

Second flag-raiser corrections

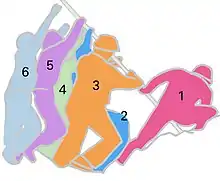

#1, Cpl. Harlon Block (KIA)

#2, Pfc. Harold Keller

#3, Pfc. Franklin Sousley (KIA)

#4, Sgt. Michael Strank (KIA)

#5, Pfc. Harold Schultz

#6, Pfc. Ira Hayes

A Marine Corps investigation of the identities of the six second flag-raisers began in December 1946 and concluded in January 1947 that it was Cpl. Harlon Block (KIA) and not Sgt. Henry Hansen (KIA) at the base of the flagstaff in the Rosenthal photograph, and that no blame was to be placed on anyone in this matter.[2] The identities of the other five second flag-raisers were confirmed.

In 2016, the Marine Corps review board launched another investigation, announcing in June 2016 that former Marine Harold Schultz was in the photograph and former Navy corpsman John Bradley was not.[7] Pfc. Franklin Sousley (KIA), not Harold Schultz, is now in the position initially ascribed to Bradley (fourth from left) in the photograph and Schultz is now in Sousley's former position (second from left) in the photograph.[7][2] The identities of the other five flag-raisers were confirmed. Schultz never publicly mentioned his role as a flag-raiser or that he was in Rosenthal's photograph.[31][32]

In October 2019, a third Marine Corps investigation concluded that former Marine Harold Keller, not Rene Gagnon (fifth from left), was actually depicted in Rosenthal's photo.[1] Gagnon who carried the larger second flag up Mount Suribachi, helped lower the first flagstaff and removed the first flag at the time the second flag was raised.[2] The identities of the other five flag raisers were confirmed. Like Schultz, Keller never publicly mentioned his role in the flag-raising or that he was in Rosenthal's photograph.

See also

- Battle of Iwo Jima

- Battle of Guam (1944)

- Flags of Our Fathers – James Bradley, 2000

- Meliton Kantaria – Soviet flag raiser over the Reichstag in Berlin, 1945

- Mikhail Yegorov – Soviet flag raiser over the Reichstag in Berlin, 1945

- Raising the Flag at Ground Zero

References

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the United States Marine Corps.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the United States Marine Corps.

- 1 2 3 "Warrior in iconic Iwo Jima flag-raising photo was misidentified, Marines Corps acknowledges". NBC News. October 16, 2019.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Robertson, Breanne, ed. (2019). Investigating Iwo: The Flag Raisings in Myth, Memory, and Esprit de Corps (PDF). Quantico, Virginia: Marine Corps History Division. pp. 243, 312. ISBN 978-0-16-095331-6.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Marine Corps University > Research > Marine Corps History Division > People > Who's Who in Marine Corps History > Gagnon - Ingram > Corporal Rene Arthur Gagnon".

- ↑ "Iwo Jima Battle War Was a Hell for Both Sides". www.stripes.com. Retrieved December 21, 2014.

- ↑ http://ruralfloridaliving.blogspot.com/2012/07/famous-floridian-friday-ernest-ivy.html Rural Florida Living. CBS Radio interview by Dan Pryor with flag raiser Ernest "Boots" Thomas on February 25, 1945 aboard the USS Eldorado (AGC-11): "Three of us actually raised the flag"

- ↑ Brown, Rodney (2019). Iwo Jima Monuments, The Untold Story. War Museum. ISBN 978-1-7334294-3-6. Retrieved April 7, 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 USMC Statement on Marine Corps Flag Raisers, Office of U.S. Marine Corps Communication, 23 June 2016

- ↑ You Tube, Smithsonian Channel, 2008 Documentary (Genaust films) "Shooting Iwo Jima" Retrieved April 7, 2020

- ↑ Silverstein, Judy, USCG (story modified 11/17/2014) USCG Veteran Provided Stars and Stripes for U.S. Marines Retrieved January 11, 2015

- ↑ The Man Who Carried the Flag on Iwo Jima, by G. Greeley Wells. New York Times, October 17, 1991, p. A 26

- ↑ Silverstein, PA2 Judy L. "USCG Veteran Provided Stars and Stripes for U.S. Marines". United States Coast Guard. Retrieved May 18, 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ "Tank Landing Ship LST".

- ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on December 19, 2014. Retrieved May 9, 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ Ira Hayes, Pima Marine, by Albert Hemingway, 1988, ISBN 0819171700

- ↑ "The Mighty Seventh War Loan". bucknell.edu. Archived from the original on April 6, 2013. Retrieved June 23, 2016.

- ↑ The Marine Corps War Memorial Archived May 29, 2016, at the Wayback Machine Marine Barracks Washington, D.C.

- ↑ "Warrior in iconic Iwo Jima flag-raising photo was misidentified, Marines Corps acknowledges". NBC News. October 16, 2019. Retrieved March 3, 2020.

- 1 2 Brown, Rodney (2019). Iwo Jima Monuments, The Untold Story. War Museum. ISBN 978-1-7334294-3-6. Retrieved March 17, 2020.

- ↑ "Memorial honoring Marines dedicated". Reading Eagle. Pennsylvania. Associated Press. November 10, 1954. p. 1.

- ↑ "Marine monument seen as symbol of hopes, dreams". Spokane Daily Chronicle. Washington. Associated Press. November 10, 1954. p. 2.

- ↑ Drake, Hal (February 21, 1965). "Flag raiser's return to Iwo Jima: 'It all seems impossible'". Stars and Stripes. Archived from the original on December 22, 2014. Retrieved August 24, 2023.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on December 22, 2014. Retrieved December 21, 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ Duckler, Ray (Concord Monitor, May 25, 2014) Ray Duckler: Son of Marine in iconic photo pay tribute to his father "Ray Duckler: Son of Marine in iconic photo pays tribute to his father | Concord Monitor". Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved January 5, 2015. Retrieved January 3, 2015

- ↑ Bradley, James and Ron Powers. Flags of Our Fathers, 2000. ISBN 0-553-11133-7

- ↑ "Iwo Jima flagraiser dies". Lewiston Morning Tribune. (Idaho). Associated Press. October 13, 1979. p. 2A.

- ↑ Wilson, Scott (2001). Resting places: the burial sites of over 7,000 famous persons. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland. ISBN 978-0786410149.

- ↑ http://newenglandtravels.blogspot.com/2011/02/iwo-jima-memorial-manchester-new.html New England Travels

- ↑ Wright Museum of WWII History

- ↑ Rene Gagnon, he was Canadian http://forums.canadiancontent.net/lounge/51882-rene-gagnon-he-canadian.html

- ↑ https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/marines-confirm-identity-man-misidentified-iconic-iwo-jima-photo-180959542/ Smithsonian Magazine, 2nd Paragraph, "the marine never publicly revealed his role"

- ↑ https://www.azcentral.com/story/news/world/2016/06/23/flag-raiser-marine-iwo-jima-photo/86254440/ "went through life without publicly revealing his role"

External links

- Corporal Rene Arthur Gagnon, USMCR Archived February 21, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, Who's Who in Marine Corps History, United States Marine Corps.

- Rene Gagnon, Famous NH People Archived June 29, 2004, at the Wayback Machine

- The Flag Raisers on Iwojima.com

- Rene A. Gagnon at IMDb