| Raposa Serra do Sol Indigenous Territory | |

|---|---|

| Terra Indígena Raposa Serra do Sol | |

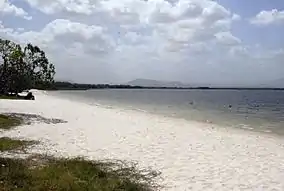

Lake Caracaranã, a sacred place of the Macuxi people located in Raposa/Serra do Sol in an area settled by farmers. Photo: Roosewelt Pinheiro/ABr | |

| |

| Coordinates | 3°50′46″N 59°46′52″W / 3.846°N 59.781°W |

| Area | 1,743,089 ha (6,730.10 sq mi) |

| Designation | Indigenous territory |

| Created | 15 April 2005 |

Terra indígena Raposa/Serra do Sol (Portuguese for Fox/Sun Hills Indigenous Land) is an indigenous territory in Brazil, intended to be home to the Macuxi people. It is located in the northern half of the Brazilian state of Roraima and is the largest in that country and one of the world's largest, with an area of 1,743,089 hectares (4,307,270 acres) and a perimeter of about 1,000 kilometres (620 mi).[1]

Location

The area includes two major natural landscapes: plains occupied by a type of vegetation similar to that of cerrado and steep mountains covered with thick rainforest. The Pacaraima Mountains in the north of the territory separate Brazil from Venezuela and Guyana. The territory contains the 116,748 hectares (288,490 acres) Monte Roraima National Park, created in 1989.[2]

Population

Raposa Serra do Sol indigenous territory is home to about 20,000 people, most of them Macuxi. Other peoples represented there are the Wapixanas, Ingaricós, Taurepangs and Patamonas, as well as non-indigenous farmers. The inhabitants of the reserve vary wildly in language and degree of cultural contact with the mainstream Brazilian culture. The Macuxis have a good degree of contact with the local non-indigenous society, while others are still outside its reach. Most of the indigenous people in the reserve do not speak Portuguese. Most of the contact the indigenous peoples have had with the mainstream society has been through FUNAI researchers, missionaries, military men, gold miners and farmers, who grow rice in the damp plains.

The presence of non-indigenous inhabitants in the reserve is not recent, but has seen a boom recently, since the reserve was proposed, because the Brazilian government usually refunds bona fide settlers for the land they forsake.[3]

History

The creation of Raposa/Serra do Sol has been the subject of sharp controversy ever since it was first proposed in 1993, for a series of reasons including concerns of national security and territorial integrity. After being identified as an Indian homeland by FUNAI, it was mapped during the Fernando Henrique Cardoso administration but was only accepted formally by president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva in 2005.[4] In May 2009 the Brazilian Supreme Court ruled that the reserve should be inhabited only by indigenous people, and an operation began to remove the remaining non-indigenous inhabitants.[5]

Concerns about the reserve started back in the 1970s, when Brazilian indigenist Orlando Villas-Boas gave a now-famous interview in which he said that the creation of Indian reserves close to border areas was a risk to the integrity of the Brazilian territory and that the action of missionaries in Brazil sought to build up national conscience among the most numerous indigenous peoples, like the Macuxi and the Yanomami, with the covert goal of establishing independent or semi-independent national entities and fragmenting the control of the Amazon jungle. The fact that the Raposa/Serra do Sol lies right along the border with Guyana and Venezuela adds to this concern.

Another major source of concern was that, after the creation of the reserve, the state of Roraima—still the least populous and the most scarcely populated Brazilian state—would have more than 54% of its area occupied by Indian reserves or national parks, which was seen by the locals as an obstacle to the state's present economic boom. Most of the rice crops of the Brazilian northern region are from within the limits of Raposa/Serra do Sol and the creation of the reserve would reduce Roraima's GDP severely. Besides large parts of other municipalities, there are an entire town, Uiramutã, and four non-Indian villages inside the territory of the reserve.

Another complicating factor is that part of the indigenous community was against the creation of an indigenous territory, because they have been coexisting with the non-native community since the beginning of the 20th century.[6] In 2006, three missionaries were kidnapped, and freed three days later by rice farmers and the indigenous people who opposed the creation of the reserve.[7]

The Monte Roraima National Park existed only on paper until 2001, when the United Nations provided money to implement and manage parks in Brazil. The indigenous people became concerned when the Brazilian Institute of Environment and Renewable Natural Resources (IBAMA) began to implement the management plan.[8] This included erecting a headquarters building, and potentially removing the indigenous Ingarikó and Macushi people from the park.[9] On 15 April 2005 the area was completely assigned to Fundação Nacional do Índio (FUNAI: National Indian Foundation) through the "dual affectation" legal device create by the federal government with recognition of the Raposa Serra do Sol Indigenous Territory.[2] Under the decree of 15 April 2005 the boundaries of the Raposa Serra do Sol Indigenous Territory were ratified and Monte Roraima National Park was made Union public property with the roles of both maintaining the constitutional rights of the Indians and conserving the environment.[10] In December 2008 the Supreme Federal Court issued a high-profile decision in favour of the continued territorial integrity of Raposa Serra do Sol. Non-indigenous rice farmers had protested their deportation from the TI, arguing that the reserve undermined Brazil's national integrity and the state's economic development, and proposing that it be broken up. The ruling established a legal precedent that affected more than 100 similar cases that were before the Supreme Court at the time, which would give birth to the Milestone thesis. [11][12]

References

- ↑ G1, "Entenda o conflito na terra indígena Raposa Serra do Sol", Globo, São Paulo, archived from the original on 2016-03-03, retrieved 2016-06-08

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - 1 2 Unidade de Conservação ... MMA.

- ↑ "Entenda o conflito na terra indígena Raposa Serra do Sol - globo.com". Archived from the original on 2008-07-06. Retrieved 2008-10-13.

- ↑ O caso da Raposa - Enciclopédia dos Povos Indígenas Archived 2008-09-23 at the Wayback Machine Instituto Socioambiental, acessada em 19 de maio de 2008.

- ↑ Brazil clears Indian reservation Archived 2009-05-03 at the Wayback Machine, BBC News, 2 May 2009

- ↑ "RR – Terra Indígena Raposa Serra do Sol". Eco Amazonia (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 10 April 2021. Retrieved 10 April 2021.

- ↑ "Missionários da Consolata já foram libertados". Agência ECCLESIA (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 10 April 2021. Retrieved 10 April 2021.

- ↑ Hillstrom & Hillstrom 2004, p. 72.

- ↑ Hillstrom & Hillstrom 2004, p. 73.

- ↑ Ghai & Cottrell 2009, p. 80.

- ↑ "Brazilian Indians 'win land case'". BBC News. 11 December 2008. Archived from the original on 13 December 2008. Retrieved 24 March 2011.

- ↑ "Brazilian court ruling backs Indian reservation". msnbc.com. 19 March 2009. Retrieved 28 March 2011.

Sources

- Ghai, Yash; Cottrell, Jill (2009-12-16), Marginalized Communities and Access to Justice, Routledge, ISBN 978-1-135-23613-7, retrieved 2016-06-08

- Hillstrom, Kevin; Hillstrom, Laurie Collier (2004), Latin America and the Caribbean: A Continental Overview of Environmental Issues, ABC-CLIO, ISBN 978-1-57607-690-3, retrieved 2016-06-08

- Unidade de Conservação: Parque Nacional do Monte Roraima (in Portuguese), MMA: Ministério do Meio Ambiente, archived from the original on 2020-10-12, retrieved 2016-06-07