| Ranworth rood screen | |

|---|---|

The Ranworth rood screen in 2023 The panel painting of the Archangel Michael Detail of the painting of St Lawrence The painting of the Virgin Mary | |

| Material | oak |

| Created | c. 1479–1480 |

| Present location | Church of St Helen, Ranworth, Norfolk, UK |

The Ranworth rood screen at Church of St Helen, Ranworth, Norfolk, is a wooden medieval rood screen that divides the chancel and nave, and was originally designed to act to separate the laity from the clergy. It is described by English Heritage as "one of England's finest painted screens".[1]

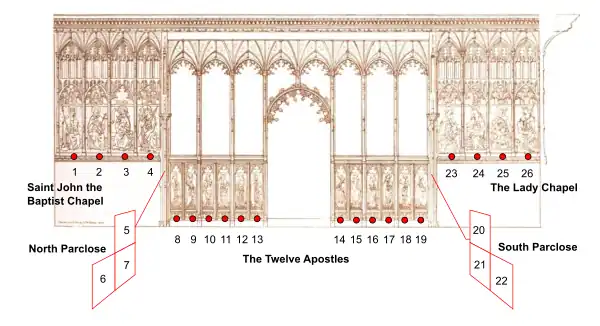

The exact date of the creation of the screen is undocumented—a date of c. 1479–1480 has been proposed by modern experts. The screen has an elaborate and coherent design, depicting 26 figures, including 12 named Apostles in the central part of the screen. The southern end, which was designed as a Lady Chapel, has panel paintings of the Virgin Mary and three other female saints.They all have a connection with childbirth and babies, which may have had a special significance for the women of the parish; it has been suggested that during the Middle Ages, women who had recently given birth came to the altar to be blessed, signifying thanks for their survival and their return from their period of lying-in.

Ranworth's rood screen survived the iconoclasm of the English Reformation. It is relatively well-preserved, but the loft parapet above the screen has not survived. Drawings of it were made in 1839 by Harriet Gunn, and it was described in detail in the 1870s. The panels at Ranworth were restored by Pauline Plummer during the 1960s and 1970s.

In 1937, the art historian Audrey Baker identified a group of East Anglian parish churches with medieval panels related to those at Ranworth; since then, screens and panel paintings from other churches have been suggested, all dating from 1470 – c. 1500. The Ranworth group is also related by the way the framed were jointed during construction, and the depiction of tiles and the use of similar and identical stencils in the panel paintings. There is evidence that the rood screens were made in the same workshop before being painted by unnamed artists in situ.

Background

Rood loft was the usual original name used for church rood screens in England. In East Anglia, medieval wills more often refer to the rodeloft, perke or candlebeam in a church. The term rood screen first arose in the early 19th century.[2]

A rood screen is a feature of Western Christian churches that was designed to divide the chancel from the nave, and so act to symbolically separate the laity from the clergy. They rose from the floor to a beam upon which a large crucifix (or “rood”) and statues of the Virgin Mary and St. John the Evangelist were displayed. There was sometimes a rood loft above the screen for holding candles, which could be large enough to enable singers to perform there on special occasions. Rood screens were prominent features in medieval European churches. [3] Norfolk has the greatest number of surviving late-medieval religious figurative screens (or panels from screens) in England, with almost 100 examples.[4]

The dating of the construction of English rood screens is mainly provided by bequests in wills. Other types of evidence used to date screens includes: the existence of a contract (which does not necessarily mean the screen was ever built under that contract);[5] the analysis of documents involving the rebuilding of the church (when a new rood screen might be constructed);[6] and the analysis of both the techniques used to construct the screen and the methods and styles employed by the artists who painted the panels.[7]

The date for the creation of the rood screen at the Church of St Helen, Ranworth, was not documented in the Middle Ages.[8] The 19th century antiquaries G.A.F. Morant and John L’Estrange associated the screen with the 1419 will of Thomas Grym and its reference to the cancellarii (lattice-work) in the church. From the date of the will, they proposed that the panels were made in c. 1417. Whilst construction dates of c. 1430, c. 1450 and c. 1479 have been proposed,[9] the screen has been dated to c. 1479–1480, which makes it contemporary with other Norfolk screens at St Michael and All Angels Church, Barton Turf (1480), Ludham (1493), St Michael's, Aylsham (1507), and Worstead (1512).[10]

Description

Screen

- St Etheldreda

- A young archbishop

- St John the Baptist

- St Barbara

- St Felix

- St George

- St Stephen

- St Simon

- St Thomas

- St Bartholomew

- St James

- St Andrew

- St Peter

- St Paul

- St John

- St Philip

- St James the Less

- St Jude

- St Matthew

- St Mary Salome

- The Virgin Mary

- Mary of Clopas

- St Margaret of Antioch

- St Thomas à Becket

- St Lawrence

- The Archangel Michael

The chancel at St Helen's is 32 feet 0 inches by 21 feet 6 inches (9.75 m × 6.55 m) and the nave is 63 feet 6 inches by 31 feet 3 inches (19.35 m × 9.53 m).[11] The rood screen, which is made of oak,[12] extends across the length of the nave, which has no aisles.[13] The screen has an elaborate and coherent design, and was built and painted in situ to a high quality.[14] The incorporation of two nave chapels on the left and right hand sides of the screen is a rare feature. They each take up four of the screen's west-facing panels, and each have two panels that are perpendicular to the main screen. The size of the side panels allows the figures on them to be less cramped-looking, and be painted more freely.[15]

The screen is one of the finest examples of its kind to have survived the iconoclasm of the English Reformation.[8] Probably the best known rood screen in England,[16] the architectural historian Nikolaus Pevsner considered it, “the finest surviving screen arrangement... in Norfolk".[17] The loft parapet that ran along the top of the screen has not survived.[17]

Screen panels

St John the Baptist altar

The four saints depicted on the north end of the rood screen, in an altar dedicated to St John the Baptist, are: St Etheldreda, an archbishop saint, St John the Baptist, and St Barbara.[18][19] The three adjoining saints on the Parclose screen are St George, St Stephen, and Felix of Burgundy.[20]

The third figure was originally designed to be of Saint John the Baptist. The work on this panel was abandoned by the medieval artist before it was finished, possibly because before the completion of the panel, it was decided to place something on the altar in front of it.[18] The saint was left unfinished and the angel above it was painted out.[19] The covering over of this panel caused an adjoining one to be amended to become the John the Baptist panel instead, as an image of the Baptist was needed for the altar.[18][19] When the screen was cleaned by restorers in the 19th century, the beard of the second panel's figure was found to have concealed a different saint. At the time it was thought that this was St Agnes. However, infrared photography has since been used to show that the figure is that of a young-looking archbishop.[18]

Apostles

The saints depicted in the central rood screen are the 12 Apostles, in the order of: St Simon, St Thomas, St Bartholomew, St James, St Andrew, St Peter on the left, and; St Paul, Saint John, St Philip, St James the Less, St Jude, St Matthew on the right.[21] The apostles are all named.[22] The saints depicted on the South Parclose are an archbishop—thought to be Archbishop Thomas Becket—as well as St Lawrence, and St Michael.[23]

Lady Altar

The Lady Altar (also referred to as the Lady Chapel) is dedicated to the Virgin Mary,[24] who is on one of four panels, all of which show or are connected with the children of female saints.[25] The other three adult figures are of St Mary Salome, St Mary Cleophas, and St Margaret of Antioch.[8][23] The Norfolk artist Cornelius Jansen Walter Winter discovered the dragon that he used to identify St Margaret of Antioch, which was previously supposed to represent St Helen.[26]

The Virgin Mary is shown with the infant Jesus on her lap as she breastfeeds him, an image that symbolised the spiritual nourishment given to worshippers by Christ.[24] Flanking her are two other saints who were, according to St Jerome, the Virgin Mary's half sisters, and the daughters of Anne. At Mary Salome's feet is her son St James, holding his emblem, a scallop shell,[24] and giving a pear to his brother St John the Evangelist, who holds a bird. Mary Cleophas, on the right of the Virgin Mary, is shown with her four boys: Simon (holding a fish), Jude (holding a boat), Joseph (with a toy windmill), and James (who is depicted blowing bubbles from a pipe). The fourth panel shows St Margaret of Antioch holding a book in one hand and thrusting a staff into the throat of a dragon with the other.[27]

The four saints each have a connection with childbirth and babies, and this may have had a special significance for the women of the parish. The historian Eamon Duffy has suggested that during the Middle Ages, women came to this altar to be blessed at least one month after childbirth, as a way of giving thanks to God for their survival, and to signify their return to church life from their period of lying-in.[24][25] A group of women, including those who assisted at the birth would have accompanied the mother. The mother's participation linked her motherhood with that of Mary, “her most celebrated figurehead”, a ritual that was symbolized by the offering of a candle “given from one mother to another”.[28]

Recording and conservation

The amateur artist Harriet Gunn and her sister Hannah visited Ranworth church four times in April 1839.[29] By January the following year, she had completed around 50 drawings of the church's rood screen.[29][note 1] The Reverend Richard Hart used a lithograph of Gunn's drawing of a bishop from the screen to illustrate a paper discussing the components of medieval vestments.[32]

A survey of the rood screens of Norfolk was carried out in 1865, and Ranworth's was described and illustrated in the following decade. An illustrated monograph was produced by Winter, and an article for the Norfolk and Norwich Archaeological Society was written by Morant and John L’Estrange.[16] They described the interior state of the building in 1872 as being “very deplorable”. A set of drawings of the screen, produced by R. O. Pearson, appeared in 1910,[16][33] the year after designs for a proposed restoration of the chancel and the screen were published by the architects William Davidson and Ebenezer James MacRae.[34][35]

The screen is well-preserved, retaining much of its coving.[14] The panel paintings were restored in the 1960s and 1970s by Pauline Plummer,[17] whose conservation reports revealed the screen suffered from “repeated episodes of iconoclastic mutilation” and a restoration that had removed areas of original paint.[29] Gunn's observations of the richness of the screen's original colours have been corroborated by the analysis of paint samples by the conservator Lucy Wrapson, which confirms they have the widest range of pigments found on any East Anglian screen.[10]

Ranworth group of rood screens

In 1937, the art historian Audrey Baker identified nine East Anglian parish churches with medieval panels related to those at Ranworth. The churches identified by Baker were Filby, North Elmham, Old Hunstanton, North Walsham, Thornham, St James Pockthorpe (Norwich), St Augustine (Norwich), Pulham St Mary, and Southwold. Since then, other churches have been suggested; in 2000, John Mitchell omitted North Walsham and Pulham St Mary.[36][note 2] Plummer identified a panel of St Apollonia, originally located in St Augustine's Church, Norwich, as an example of a painting from the Ranworth group. Wrapson considers the Ranworth group to consist of extant screens or fragments from Ranworth, Old Hunstanton, Thornham, Filby, Southwold [centre screen], North Elmham, St James Pockthorpe [Norwich], North Walsham, and the St Apollonia panel.[38]

Evidence suggests that the panels in the group identified by Wrapson are related by their date of construction, which has been determined using bequests that mention the screens, and the results of dendrochronology:[39]

| Location/panel | Bequest dates | Other dates |

|---|---|---|

| Ranworth | 1479 | |

| Old Hunstanton | unknown | |

| Thornham | before 1488 | |

| Filby | 1471; 1503 | |

| Southwold | 1450s – 1480s | c. 1500 (based on the screen structure and the design of the panel) |

| North Elmham | 1474 | |

| St James Pockthorpe [Norwich] | 1479 | 1459 – 1494 (dendrochronology) |

| North Walsham | after c. 1470 | |

| St Apollonia panel | unknown |

.jpg.webp)

The Ranworth group of screens are also related in the way the frames were constructed, as well as in their decorative schemes. They were made using similar jointing techniques,[41] and six of the screens have a common floral pattern made by stencilling, a technique used extensively for many years. The same stencil was used at St James Pockthorpe and North Walsham, and a different one at both North Walsham and at Southwold. Two other groups of panels, Ranworth/Old Hunstanton/Filby and Filby/Thornham/North Elmham, share identical stencils. Baker noted the painting of the flooring in the panels as typical of the Ranworth group, where tilings had been used in a purely decorative way, without any attempt to show perspective.[7]

More than one artist painted the panels for the Ranworth group of screens, but none of their names are documented.[14] Despite a lack of evidence with respect to the names of the individual artists, the screens are thought to have been produced from a single workshop,[42] with different aspects of the panels being assigned to different artists.[43]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Harriet Gunn was the third daughter of the polymath Dawson Turner. She married the geologist John Gunn.[30] Her 250 drawings of Norfolk’s rood screens, which she produced from c. 1830 onwards, represent “the first serious attempt” to document the county's rood screens.[31]

- ↑ The surviving panels from St James are at St Mary Magdalene Church, Norwich.[37]

References

- ↑ Historic England. "Church of St Helen, Ranworth (Grade I) (1154645)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 30 December 2023.

- ↑ Wrapson 2012, pp. 388–389.

- ↑ Kuiper, Kathleen. "rood screen". Britannica. Retrieved 2 January 2024.

- ↑ Wrapson 2012, p. 386.

- ↑ Cotton, Lunnon & Wrapson 2014, p. 219.

- ↑ Cotton, Lunnon & Wrapson 2014, p. 220.

- 1 2 Wrapson 2012, pp. 401–403.

- 1 2 3 Graham-Dixon 1999, p. 21.

- ↑ Wrapson 2015a, p. 7.

- 1 2 Snape 2023, p. 349.

- ↑ Morant & L'Estrange 1872, p. 178.

- ↑ "The rood screen and lectern of Ranworth Church". The Artist. 1898. Retrieved 3 January 2024 – via Proquest.

- ↑ Strange 1902, p. 4.

- 1 2 3 Wrapson 2015a, p. 2.

- ↑ Wrapson 2015a, pp. 2, 10.

- 1 2 3 Wrapson 2015a, p. 1.

- 1 2 3 Pevsner & Wilson 2002, p. 643.

- 1 2 3 4 "Saint John the Baptist Chapel". St Helen's Church. Retrieved 2 January 2024.

- 1 2 3 Wrapson 2015a, p. 5.

- ↑ Strange 1902, pp. 8–11.

- ↑ Strange 1902, p. 12.

- ↑ Morant & L'Estrange 1872, p. 182.

- 1 2 "Parcloses". St Helen's Church. Retrieved 17 December 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 "The Lady Chapel". St Helen's Church. Retrieved 19 December 2023.

- 1 2 Duffy 2005, p. 181.

- ↑ Morant & L'Estrange 1872, p. 183.

- ↑ Strange 1902, pp. 12–13.

- ↑ Niebrzydowski 2011, pp. 331–332.

- 1 2 3 Snape 2023, p. 346.

- ↑ "Harriet Gunn (Author), British Travel Writing". Archived from the original on 17 October 2017. Retrieved 17 October 2017.

- ↑ Snape 2023, p. 333.

- ↑ Snape 2023, p. 353.

- ↑ Morant & L'Estrange 1872, p. 180.

- ↑ "Basic Site Details: Church of St Helen". Dictionary of Scottish Architects. 2016. Retrieved 17 December 2023.

- ↑ "St. Helen's Church, Ranworth, Norfolk: Proposed Restoration". The Building News. Vol. 99, no. 2905. 9 September 1910. pp. 362–363. Retrieved 16 December 2023.

- ↑ Wrapson 2012, pp. 391–392.

- ↑ Wrapson 2012, p. 391.

- ↑ Wrapson 2015a, pp. 2–3.

- ↑ Wrapson 2015a, p. 8.

- ↑ Wrapson 2015a, pp. 6–9.

- ↑ Wrapson 2012, p. 402.

- ↑ Wrapson 2012, pp. 392, 402.

- ↑ Wrapson 2015a, pp. 10–11.

Sources

- Cotton, Simon A.; Lunnon, Helen E.; Wrapson, Lucy (2014). "Medieval rood screens in Suffolk: their construction and painting dates" (PDF). Proceedings of the Suffolk Institute of Archaeology and History. 43 (2): 219–234.

- Duffy, Eamon (2005). The Stripping of the Altars: Traditional Religion in England, c.1400-c.1580. New Haven, Connecticut; London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-03001-0-828-6.

- Graham-Dixon, Andrew (1999). A History of British Art. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. ISBN 978-05202-237-69.

- Morant, G. A. F.; L'Estrange, John (1872). "Notices of the church at Randworth, Walsham Hundred". Norfolk Archaeology. Norwich, UK. 7: 178–211.

- Niebrzydowski, Sue (2011). "Asperges me, Domine, hyssopo: male voices, female interpretation and the medieval English purification of women after childbirth ceremony". Early Music. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. 39 (3): 327–333.

- Pevsner, Nikolaus; Wilson, Bill (2002). Norfolk 1: Norwich and North-East. The Buildings of England. New Haven, Connecticut; London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-03000-9-607-1.

- Snape, Julia (2023). "'We Would Take the Screen by Storm': Female Antiquarian Agency and the Capture of English Medieval Painting c.1830–50". The Antiquaries Journal. Society of Antiquaries of London. 103: 333–362. doi:10.1017/S0003581523000124.

- Strange, Edward Fairbrother (1902). The Rood-Screen of Ranworth Church. Norwich, UK: Jarrold. OCLC 2963375.

- Wrapson, Lucy (2012). "East Anglian Rood-screens: the Practicalities of Production". In Binski, P.; New, E. (eds.). Patrons and Professionals in the Middle Ages: Proceedings of the 2010 Harlaxton Symposium (Conference paper). Donington. pp. 386–404. ISBN 978-19077-3-012-2.

- Wrapson, Lucy (2015a). "Ranworth and its Associated Paintings: A Norwich Workshop". In Heslop, T.; Lunnon (eds.). Norwich: Medieval and Early Modern Art, Architecture and Archaeology. The British Archaeological Association Conference Transactions. Vol. 38. Leeds, UK: Maney Publishing. ISBN 978-19096-6-277-3.

Further reading

- Hart, Richard (1847). "Description of the engraving from the Randworth screen chiefly as it illustrates the ecclesiastical vestments of our church during the middle ages". Norfolk Archaeology. Norwich, UK. 1 (1): 324–333. doi:10.5284/1077244.

- Wrapson, Lucy (2015b). "A Medieval Context for the Artistic Production of Painted Surfaces in England Evidence from East Anglia c.1400–1540". In Cooper, Tarnya; Burnstock, Aviva; Howard, Maurice; Town, Edward (eds.). Painting in Britain 1500–1630: Production, Influences and Patronage. London: Oxford University Press. pp. 166–175. ISBN 978-01972-6-584-0.

External links

- Images of the Ranworth rood screen by Martin Harris

- 'St Helen, Ranworth from the Norfolk Churches website (self-published)

- Cornelius Jansen Walter Winter's Illustrations of the Rood-screen at Randworth (1867) from the Hathi Trust

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)