A qalam (Arabic: قلم) is a type of reed pen. It is made from a cut, dried reed, and used for Islamic calligraphy. The pen is seen as an important symbol of wisdom in Islam, and references the emphasis on knowledge and education within the Islamic tradition.

Etymology

The word was borrowed from Greek kálamos (κάλαμος, "reed"), [1] possibly via Ge'ez ḳäläm (ቀለም, "reed") mixed into the root of ḳälämä (ቀለመ, "to color, to stain, to write").[2][3]

Manufacturing

The stems of hollow reeds are cut at specific angles depending on intended script[4] so that they can be used for calligraphy, and the type of reed used varies depending on the specific calligrapher's preferences. For example, master calligrapher Ja'far Tabrizi preferred the wāṣeṭi and āmuyi reeds of eastern Iraq and the Oxus River, respectively.[5] It was desired that the qalam should be roughly twelve to sixteen inches long, and could not be too dry as they needed to be a specific balance of not too sturdy and not too flexible.[6]

Qalam in the Islamic tradition

The concepts of knowledge and writing are very important in Islam, and thus the qalam is revered as a symbol of wisdom and education in the Qur'an; Sura 68 is called Al-Qalam. Even in pre-Islamic societies, writing was widely used for commercial and occasionally legislative purposes.[7] It is a commonly held belief amongst the Muslim population that disrespect of calligraphy as a tradition would reveal a person as being uneducated and unwise.[8] In Islam, the physical presence of the written letters of the Quran functioned the way icons did to the Byzantines, as a blessing and protection. Because of this, Islamic calligraphers often had a high place in society, while their counterparts in regions like Byzantium would only be known to their family and patrons.[9]

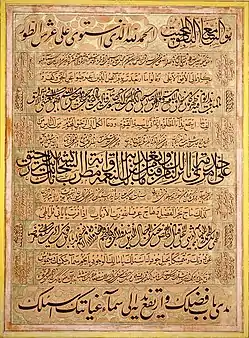

Calligraphy holds a central position in the Islamic artistic tradition, and because of this there exist a large variety of accessories to accompany the qalam and its user, such as pen boxes, ink wells, and knives for cutting the reeds. These tools were often very ornamented and cherished objects and reflected countless hours of other artists and craftsmen.[10] The ink used in antiquity was most frequently black or dark brown, and was made from gum arabic, soot, gallnuts, or vitriol. Some Qurans, however, are written entirely in gold, and more contemporary calligraphers may use a wider variety of colors. Abu Ali Muhammad ibn Muqla, a Persian official of the Abbasid caliphate, developed a standardized system of writing calligraphy based on the marks made with the point of a reed pen, in combination with other geometric principles.[4] As far as other aspects of ornamentation go, metallic inks on colored parchment passed from Byzantium to Muslim Spain, and Arabic calligraphy in turn made its way back to Europe.[9]

See also

References

- ↑ Gacek, Adam (2008). The Arabic Manuscript Tradition: A Glossary of Technical Terms. Leiden: Brill. p. 65. ISBN 9789004120617.

- ↑ Jeffery, Arthur (1938). The Foreign Vocabulary of the Qurʾān. Baroda: Oriental Institute. pp. 242–243.

- ↑ Nöldeke, Theodor (1910). Neue Beiträge zur semitischen Sprachwissenschaft. Straßburg: Karl J. Trübner. p. 50.

- 1 2 von Folsach, Kjeld (2001). Art from the World of Islam in the David Collection. Copenhagen: F. Hendriksens Eftf. p. 40. ISBN 87-88464-21-0.

- ↑ Goudarzi, Sina (19 May 2016). "Qalam". Iranic Online. Retrieved 12 December 2018.

- ↑ Huart; Grohmann (2012). "Ḳalam". Second.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Bloom, Blair, Jonathan, Sheila (1997). Islamic Arts. London: Phaidon Press Ltd. ISBN 071483176X.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Mansour, Nassar (2011). Sacred Script: Muhaqqaq in Islamic Calligraphy. I.B.Tauris. pp. 149–150. ISBN 978-1848854390.

- 1 2 Bierman, Irene A. (2005). The Experience of Islamic Art on the Margins of Islam. Reading: Garnet Publishing Ltd. ISBN 9780863723001.

- ↑ I. McWilliams II. Roxburgh, I. Mary II. David (2007). Traces of the Calligrapher: Islamic Calligraphy in Practice, c. 1600-1900. The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. p. 9. ISBN 978-0300126327.