| Pygmalion | |

|---|---|

| King of Tyre | |

| King of Tyre | |

| Reign | 831 BCE – 785 BCE |

| Predecessor | Mattan I |

| Successor | unknown |

| Born | 841 or 843 BCE Tyre, presumed |

| Died | 785 BCE |

| Dynasty | House of Ithobaal I |

| Father | Mattan I |

| Mother | unknown |

Pygmalion (Ancient Greek: Πυγμαλίων Pugmaliōn; Latin: Pygmalion), was king of Tyre[1] from 831 to 785 BCE and a son of King Mattan I (840–832 BCE).

During Pygmalion's reign, Tyre seems to have shifted the heart of its trading empire from the Middle East to the Mediterranean, as can be judged from the building of new colonies including Kition on Cyprus, Sardinia (see Nora Stone discussion below), and, according to tradition, Carthage. For the story surrounding the founding of Carthage, see Dido.

Name

The Latin spelling Pygmalion represents the Greek Πυγμαλίων Pugmaliōn.

The Greek form of the name has been identified as representing the Phoenician Pumayyaton (or Pūmayyātān). This name is recorded epigraphically, as 𐤐𐤌𐤉𐤉𐤕𐤍, PMYYTN, a theophoric name interpreted as meaning "Pummay has given". This historical Pumayyaton however, was a Cypriot "king of Kition, Idalion and Tamassos", not of Tyre, and lived several centuries after Pygmalion of Tyre's supposed lifetime.[2]

The Nora Stone, discovered in 1773, has also been read as containing the name Pum(m)ay (PMY) by Frank Moore Cross in 1972. Cross has identified this PMY with Pumayyatan and further with Pygmalion of Tyre. This is highly speculative, and there is no consensus whatsoever on the interpretation of the inscription, not even on whether the text is intended as being read in boustrophedon.[3]

There is also epigraphic attestation of an apparent theonym PGMLYN (𐤐𐤂𐤌𐤋𐤉𐤍) found on inscriptions such as the Douïmès medallion. This may either suggest an alternative Phoenician etymology for the name, or it may simply be a Phoenician attempt at transliterating the Greek form of the name; though in the case of the Douïmès medallion, the supposed age of the artefact may present some difficulties for the latter hypothesis.[4]

Date

Pygmalion's dates are derived from Josephus's Against Apion i.18, where Josephus quotes the Phoenician historian Menander as follows:

Pygmalion . . . lived fifty-six years,[5] and reigned forty-seven years. Now, in the seventh year of his reign, his sister fled away from him, and built the city of Carthage in Libya.

Pygmalion's dates, if this citation is to be trusted, are thus dependent on the date of the founding of Carthage. Here ancient classical sources given two possibilities: 825 BCE or 814 BCE. The 814 date is derived from the Greek historian Timaeus (c. 345–260 BCE), and is the more commonly accepted year. The 825 date is taken from the writings of Pompeius Trogus (1st century BCE), whose forty-four book Philippic History survives only in abridged form in the works of the Roman historian Justin. In a 1951 article, J. Liver argued that the 825 date has some credibility because, with it, the elapsed time between that date and the start of building of Solomon's Temple, given as 143 years and 8 months in Menander/Josephus, agrees very closely with the date of approximately 967 BCE for the start of Temple construction as derived from 1 Kings 6:1 (fourth year of Solomon) and the date given by most historians for the end of Solomon's forty-year reign, i.e. 932 or 931 BCE.[6] If, however, the starting place is 814 BCE, measuring back 143 or 144 years does not agree with this Biblical date.

Liver advanced a second reason to favor the 825 date, related to the inscription of Shalmaneser III, king of Assyria, mentioned below, where it was mentioned that philological studies have equated this Ba'li-manzer with Balazeros (Baal-Eser II), grandfather of Pygmalion. The best texts of Menander/Josephus give six years for Balazeros, followed by nine years for his son and successor Mattenos (Mattan I), making 22 years between the start of Balazeros's reign and the seventh year of Pygmalion. If these 22 years are measured back from 814 BCE, they fall short of the 841 date required for Balazeros's tribute to Shalmaneser. With the 825 date, however, Balazeros's last year would be approximately 841 BCE, the time of the tribute to Shalmaneser.

These two agreements, one with an Assyrian inscription and the other with a Biblical datum, have proved quite convincing to scholars such as J. M. Peñuela,[7] F. M. Cross.,[8] and William H. Barnes.[9] Peñuela points out that the following consideration reconciles the two dates for Carthage derived from classical authors: 825 BCE was the year that Dido fled Tyre, and she did not found Carthage until 11 years later, in 814 BCE. Josephus, citing Menander, says that "in the seventh year of [Pygmalion's] reign, his sister fled away from him, and built the city of Carthage in Libya" (Against Apion i:18). There are two events mentioned here: the flight from Tyre and the founding of Carthage. The language used would suggest that it was the first of these events, Dido's flight, that took place in Pygmalion's seventh year. Between the two events the following took place: Dido and her ships sailed to Cyprus, where about 80 of the men with her took wives. Eventually the Tyrians arrived on the north coast of Africa, where they received permission to build on an island in the harbor of the place where Carthage was eventually to be built. Peñuela quotes Strabo to show that some time then elapsed before the founding of Carthage: "Carthage was not founded immediately. Indeed, a small island having been captured previously in the Carthaginian harbor, Dido settled there. She fortified the place, which she used as a citadel of war against the Africans, who kept her from the shore."[10] Justin (18:5 10–17) also mentions the time on this island, which he names as Cothon, and says that Dido and her company built a circle of houses there.[10] Eventually peace was made with the inhabitants on the mainland, and the Tyrians were given permission to build a city. Peñuela maintained that these various events between the departure from Tyre and the eventual rapprochement with the inhabitants on the mainland explain the eleven-year difference between Pompeius Trogus's date of 825 BCE and the 814 date derived from other classical authors for Carthage's founding.

This understanding of the chronology related to Dido and her company resulted in the following dates for Pygmalion, Dido, and their immediate relations, as derived from F. M. Cross[8] and Wm. H. Barnes:[11]

- Baal-Eser II (Baʿl-mazzer II) 846–841 BCE

- Mattan I 840–832 BCE

- 831 BCE: Pygmalion begins to reign

- 825 BCE: Dido flees Tyre in 7th year of Pygmalion

- 825 BCE and possibly some time thereafter: Dido and companions on Cyprus

- Between 825 BCE and 814 BCE: Tyrians build settlement on island of Cothon

- 814 BCE: Dido founds Carthage on mainland

- 785 BCE: Death of Pygmalion

Epigraphic evidence

The Nora Stone

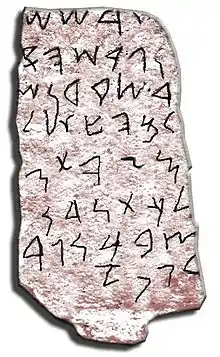

A possible reference to Pygmalion is an interpretation of the Nora Stone, found on Sardinia in 1773 and, though its precise finding place has been forgotten, dated by paleographic methods to the 9th century BCE.[12] Frank Moore Cross in 1972 has interpreted the Phoenician inscription on this stone as containing a reference to a king "Pumay":[13]

- "[ He fought (?) with the Sardinians (?)] at Tarshish and he drove them out. Among the Sardinians he is [now] at peace, (and) his army is at peace: Milkaton son of Shubna (Shebna), general of (king) Pummay."

In this rendering, Cross has restored the missing top of the tablet (estimated at two lines) based on the content of the rest of the inscription, as referring to a battle that has been fought and won. Cross conjectured that Tarshish here "is most easily understood as the name of a refinery town in Sardinia, presumably Nora or an ancient site nearby."[13] He takes the PMY ("Pummay") in the last line as a shortened form of the name of Shubna's king, containing only the divine name, a method of shortening "not rare in Phoenician and related Canaanite dialects".[14] Since there was only one king of Tyre with this hypocoristicon in the 9th century BCE, Cross restores the name to pmy(y)tn or pʿmytn, which is rendered in the Greek tradition as Pygmalion.

There is no consensus whatsoever on the reading of this inscription. Most scholars do not attempt to offer a translation. One alternative interpretation suggests an entirely different meaning: "the text honours a god, most probably in thanks for the traveller's safe arrival after a storm".[15]

Tribute of Balazeros (Baalimanzer) to Shalmaneser III

In 1951, Fuad Safar published a record of tribute from Baaʿli-maanzer, king of Tyre, to Shalmaneser III of Assyria in 841 BCE.[16] There followed several studies that attempted to relate this Baaʿli-maanzer to the list of kings given in Menander/Josephus. It was argued, based on philological considerations, that the name as given in the Assyrian text could be matched to a Phoenician Baʿal-ʿazor and the Greek Baal-Eser/Balazeros, a name corresponding to two kings in Menander's list.[17][18][19][20] The first Balazeros was a son of Hiram I, contemporary of David and Solomon, so this was too early, but the second name referred to the grandfather of Pygmalion and was therefore in the right date range.

See also

References

- ↑ The traditional king-list of Tyre is derived from Josephus, Against Apion i. 18, 21, and Jewish Antiquities viii. 5.3; 13.2. His list was based on Menander of Ephesus, who drew his information from the chronicles of Tyre. (Jewish Encyclopedia: "Phenicia").

- ↑ Frank Moore Cross, Leaves from an Epigrapher's Notebook: Collected Papers in Hebrew and West Semitic Palaeography and Epigraphy, Brill (2018 [1974]), p. 278.

- ↑ Brian Peckham: The Nora Inscription. In: Orientalia 41, 1972, S. 457–468.

- ↑ Philip Schmitz, Deity and Royalty in Dedicatory Formulae: The Ekron Store-Jar Inscription Viewed in the Light of Judg 7:18, 20 and the Inscribed Gold Medallion from the Douïmès Necropolis at Carthage (KAI 73). Maarav 15.2 (2008): 165–73: "Scholars understandably expressed disbelief about this identification: “it is easily conceivable that the gem was dedicated to Astarte and Pygmalion and in the process acquired the inscription,” mused M. Lidzbarski before reflecting on the difficulty of explaining a transliterated Greek name in an inscription of such apparently early date. The notion that the object must have become an heirloom, and is thus earlier than the tomb in which it was discovered, has had wide circulation. I agree that this is probably the best explanation of its archaeological context."

- ↑ The copies of Josephus/Menander in the Codex Laurentianus, the old Latin version of Cassiodorus, and Theodotion give 56 years; copies of Eusebius's "Chronography" in Armenian, plus some Greek extracts of it, give 58 years. From Barnes, Studies 40, note n.

- ↑ J. Liver, "The Chronology of Tyre at the Beginning of the First Millennium B.C.", Israel Exploration Journal 3 (1953) 116–117.

- ↑ Peñuela, "La Inscripción Asiria", (Part 1), 217–37 and (Part 2) Sefarad 14 (1954) 1–39.

- 1 2 Cross, "Nora Stone" 17, n. 11.

- ↑ Barnes, Studies 51–53.

- 1 2 Strabo (17:3 14–15), cited in Peñuela, "La Inscripción Asiria" Part 2, p. 29, note 167.

- ↑ Barnes, Studies 53.

- ↑ c. 825–780 according to Robin Lane Fox, Travelling Heroes in the Epic Age of Homer, 2008:120f and note p. 382.

- 1 2 F. M. Cross, "An Interpretation of the Nora Stone", Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 208 (Dec. 1972) 16.

- ↑ F. M. Cross, "An Interpretation of the Nora Stone", Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 208 (Dec. 1972) 17.

- ↑ Fox 2008:121, following for the c. 800 date, E. Lipinski, "The Nora fragment", Mediterraneo antico 2 (1999:667–71), for the reconstruction of the text see Lipinski2004:234–46, rejecting Cross.

- ↑ Fuad Safar, "A Further Text of Shalmaneser III from Assur", Sumer 7 (1951) 3–21.

- ↑ J. Liver, "The Chronology of Tyre at the Beginning of the First Millennium B.C." Israel Exploration Journal 3 (1953) 119–120.

- ↑ J. M. Peñuela, "La Inscripción Asiria IM 55644 y la Cronología de los Reyes de Tiro", Sefarad 13 (1953, Part 1) 219–28.

- ↑ Cross, "Nora Stone", 17, n. 11.

- ↑ William H. Barnes, Studies in the Chronology of the Divided Monarchy of Israel (Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1991) 29–55.