Pushmataha | |

|---|---|

| Apushamatahahubi (Choctaw) | |

Pushmataha, 1824, from History of the Indian Tribes of North America | |

| High Chief of the Choctaws | |

| In office 1815–1824 | |

| Succeeded by | Chief Oklahoma (nephew) |

| Chief of the Six Towns District | |

| In office 1800–1824 | |

| Succeeded by | Tappenahoma[1] |

| Personal details | |

| Born | c. 1764 Taladega, Choctaw Nation |

| Died | December 24, 1824 (aged 59–60) Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Resting place | Congressional Cemetery, Washington, D.C. |

| Children | 5 |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | |

| Rank | |

| Battles/wars | War of 1812 |

Pushmataha (c. 1764 – December 24, 1824; also spelled Pooshawattaha, Pooshamallaha, or Poosha Matthaw), the "Indian General", was one of the three regional chiefs of the major divisions of the Choctaw in the 19th century. Many historians considered him the "greatest of all Choctaw chiefs".[2] Pushmataha was highly regarded among Native Americans, Europeans, and white Americans, for his skill and cunning in both war and diplomacy.

Rejecting the offers of alliance and reconquest proffered by Tecumseh, Pushmataha led the Choctaw to fight on the side of the United States in the War of 1812. He negotiated several treaties with the United States.

In 1824, he traveled to Washington to petition the Federal government against further cessions of Choctaw land; he met with John C. Calhoun and Marquis de Lafayette, and his portrait was painted by Charles Bird King. He died in the capital city and was buried with full military honors in the Congressional Cemetery in Washington, D.C.

Name

The exact meaning of Pushmataha's name is unknown, though scholars agree that it suggests connotations of "ending". Many possible etymologies have been suggested:

- Apushamatahahubi: "a messenger of death; literally one whose rifle, tomahawk, or bow is alike fatal in war or hunting."[2]

- Apushim-alhtaha, "the sapling is ready, or finished, for him."[3]

- Pushmataha, "the warrior's seat is finished."[4]

- Pushmataha, "He has won all the honors of his race."[5]

- Apushimataha, "No more in the bag."[6]

Early life

Pushmataha's early life is poorly documented. His parents are unknown, possibly killed in a raid by a neighboring tribe. Pushmataha never spoke of his ancestors; a legend of his origin was told:

A little cloud was once seen in the northern sky. It came before a rushing wind, and covered the Choctaw country with darkness. Out of it flew an angry fire. It struck a large oak, and scattered its limbs and its trunk all along the ground, and from that spot sprung forth a warrior fully armed for war.[4]

Most historians agree that he was born in 1764 in the normal manner near the future site of Macon, Mississippi, Choctaw Country.[6]

When he was 13, Pushmataha fought in a war against the Creek people.[7] Some sources report that he was given the early warrior-name of "Eagle". Better attested is his participation in wars with the Osage and Caddo tribes west of the Mississippi River between 1784 and 1789.[2][8] He served as a warrior in other conflicts into the first decade of the 1800s, and by then his reputation as a warrior was made. These conflicts were due to depletion of the traditional deer-hunting grounds of the Choctaw around their holy site of Nanih Waiya. Population had increased in the area, and competition among tribes over the fur trade with Europeans exacerbated violent conflict. The Choctaw raided traditional hunting grounds of other tribes for deer.[9] Pushmataha's raids extended into the territories that would become the states of Arkansas and Oklahoma. His experience and knowledge of the lands would prove invaluable for later negotiations with the US government for those same lands.

Chief of the Six Towns district

By 1800, Pushmataha was recognized as a military and spiritual leader, and he was chosen as the mingo (chief) of the Okla Hannali or Six Towns district of the Choctaw. (One of three in the Choctaw tribe, this covered the southern part of their territory, primarily in Mississippi). His sharp logic, humorous wit, and lyrical, eloquent speaking style quickly earned him renown in councils.[9] Pushmataha rapidly took a central position in diplomacy, first meeting with United States envoys at Fort Confederation in 1802.[9] Pushmataha negotiated the Treaty of Mount Dexter with the United States on November 16, 1805,[5][10] and met Thomas Jefferson during his term as president.

War of 1812

Portraits of Pushmataha (left) and Tecumseh. |

| "These white Americans ... give us fair exchange, their cloth, their guns, their tools, implements, and other things which the Choctaws need but do not make ... They doctored our sick; they clothed our suffering; they fed our hungry ... So in marked contrast with the experience of the Shawnees, it will be seen that the whites and Indians in this section are living on friendly and mutually beneficial terms." Pushmataha, 1811 – Sharing Choctaw History.[8] --------------------- "Where today are the Pequot? Where are the Narragansett, the Mochican, the Pocanet, and other powerful tribes of our people? They have vanished before the avarice and oppression of the white man, as snow before the summer sun ... Sleep not longer, O Choctaws and Chickasaws ... Will not the bones of our dead be plowed up, and their graves turned into plowed fields?" Tecumseh, 1811 – The Portable North American Indian Reader.[11] |

Early in 1811, Tecumseh garnered support for his British-backed attempt to recover lands from the United States settlers. As chief for the Six Towns district, Pushmataha strongly resisted such a plan, pointing out that the Choctaw and their neighbors the Chickasaw had always lived in peace with European Americans, had learned valuable skills and technologies, and had received honest treatment and fair trade.[8] The joint Choctaw-Chickasaw council voted against alliance with Tecumseh. When Tecumseh departed, Pushmataha accused him of tyranny over his own Shawnee tribe and other tribes. He warned Tecumseh that he would fight against those who fought the United States.[12]

With the outbreak of war, Pushmataha led the Choctaw in alliance with the United States. He argued against the Creek alliance with Britain after the massacre at Fort Mims.[9] In mid-1813, Pushmataha went to St. Stephens, Alabama, with an offer of alliance and recruitment of warriors. He was escorted to Mobile to speak with General Flournoy, then commanding the district. Flournoy initially declined Pushmataha's offer and offended the chief. Flournoy's staff quickly convinced the general to reverse his decision. A courier carrying a message accepting Pushmataha's offer caught up with the chief at St. Stephens.[13]

Returning to Choctaw territory, Pushmataha raised a company of 500 warriors. He was commissioned (as either a lieutenant colonel or a brigadier general) in the United States Army at St. Stephens. After observing that the officers and their wives would promenade along the Tombigbee River, Pushmataha invited his wife to St. Stephens and took part in this custom.

Under Brigadier General Ferdinand Claiborne, Pushmataha and 150 Choctaw warriors took part in an attack on Creek forces at the Battle of Holy Ground, also known as Kantachi or Econochaca, on December 23, 1813.[5][13] With this victory, Choctaw began to volunteer in greater numbers from the other two districts of the tribe. By February 1814, Pushmataha led a larger band of Choctaws and joined General Andrew Jackson's force to sweep the Creek territories near Pensacola. Many Choctaw departed after the final defeat of the Creek at Horseshoe Bend.

By the Battle of New Orleans, only a few Choctaw remained with the army. They were the only Native American tribe represented in the battle. Some sources say Pushmataha was among them, while others disagree. Another Choctaw division chief, Mushulatubbee, led about 50 of his warriors in this battle.

Pushmataha was regarded as a strict war leader, marshaling his warriors with discipline. U.S. Army officers impressed with his leadership skills called him "The Indian General".

Principal Chief of the Choctaw

On his return from the wars, Pushmataha was elected paramount chief of the Choctaw nation. A cultural conservative, Pushamataha resisted the efforts of Protestant missionaries, who arrived in Choctaw territory in 1818.[9] But he agreed with learning new technologies and useful practices from the Americans, including the adoption of cotton gins, agricultural practices, and military disciplines.[8] He devoted much of his military pension to funding a Choctaw school system,[5] and had his five children educated as well as possible.[4]

Pushmataha negotiated two more land-cession treaties with the United States. While the treaty of October 24, 1816, was counted of little loss, composed mainly of hunted-out grounds, the Treaty of Doak's Stand (signed October 18, 1820) was highly contentious. European-American settlement was encroaching on core lands of the Choctaw. Although the government offered equivalent-sized plots of land in the future states of Arkansas and Oklahoma, Pushmataha knew the lands were less fertile and that European-American squatters were already settling in the territory. "He displayed much diplomacy and showed a business capacity equal to that of Gen. Jackson, against whom he was pitted, in driving a sharp bargain."[5] Reportedly, in a tense exchange with Andrew Jackson, they exchanged frank views:

Gen. Jackson put on all his dignity and thus addressed the chief: "I wish you to understand that I am Andrew Jackson, and, by the Eternal, you shall sign that treaty as I have prepared it. The mighty Choctaw Chief was not disconcerted by this haughty address, and springing suddenly to his feet, and imitating the manner of his opponent, replied, "I know very well who you are, but I wish you to understand that I am Pushmataha, head chief of the Choctaws; and, by the Eternal, I will not sign that treaty."

Pushmataha signed only after securing guarantees in the text of the treaty that the US would evict squatters from reserved lands.

Journey to Washington

In 1824, Pushmataha was upset about encroaching settlement patterns and the unwillingness of local authorities to respect Indian land title. He took his case directly to the Federal government in Washington, D.C. Leading a delegation of two other regional chiefs (Apuckshunubbee and Mosholatubbee), he sought either expulsion of white settlers from deeded lands in Arkansas, or compensation in land and cash for such lands.[9] The group included Talking Warrior, Red Fort, Nittahkachee, Col. Robert Cole and David Folsom, both mixed-race Choctaw; Captain Daniel McCurtain; and Major John Pitchlynn (married to a Choctaw), the official U.S. Interpreter.[14]

The delegation planned to travel the Natchez Trace to Nashville, then to Lexington and Maysville, Kentucky; across the Ohio River (called the Spaylaywitheepi by the Shawnee) to Chillicothe, Ohio (former principal town of the Shawnee); and east along the "National Highway" to Washington City. [14]

Pushmataha met with President James Monroe, and gave a speech to Secretary of War John C. Calhoun. He reminded Calhoun of the longstanding alliances between the United States and the Choctaw.[15] He said, "[I] can say and tell the truth that no Choctaw ever drew his bow against the United States ... My nation has given of their country until it is very small. We are in trouble." (Hewitt 1995:51–52)

While in Washington, Pushmataha sat in his Army uniform for a portrait by Charles Bird King; it hung in the Smithsonian Institution until 1865. While the original was destroyed by a fire that year, numerous prints had been made. It has become the most famous likeness of Pushmataha. Chief Pushmataha also met with the Marquis de Lafayette, who was visiting Washington, D.C., for the last time. Pushmataha hailed Lafayette as a fellow aged warrior who, though foreign, rose to high renown in the American cause.

Death and burial

In December 1824, Pushmataha acquired a viral respiratory infection, then called the croup. He quickly became seriously ill and was visited by Andrew Jackson. On his deathbed, Pushmataha reflected that the national capital was a good place to die. Pushmataha's chosen assistant also happened to suddenly die on the return journey from Washington, D.C., to Choctaw lands in present day Mississippi.

Pushmataha requested full military honors for his funeral, and gave specific instructions as to his effects. His last recorded words were these:

I am about to die, but you will return to our country. As you go along the paths, you will see the flowers, and hear the birds sing; but Pushmataha will see and hear them no more. When you reach home they will ask you, 'Where is Pushmataha?' And you will say to them, 'He is no more.' They will hear your words as they do the fall of the great oak in the stillness of the midnight woods.[4]

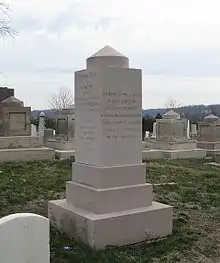

Pushmataha died on December 24, 1824. As requested, he was buried with full military honors as a brigadier general of the U.S. Army, in the Congressional Cemetery in Washington. He is one of two Native American chiefs interred there, the other being Peter Pitchlynn, also a Choctaw.

His epitaph, inscribed in upper case letters, reads:

Push-ma-ta-ha, a Choctaw chief, lies here. This monument to his memory is erected by his brother chiefs who were associated with him in a delegation from their nation in the year 1824 to the general government of the United States.

Push-ma-ta-ha was a warrior of great distinction he was wise in council – eloquent in an extraordinary degree, and on all occasions & under all circumstances the white man's friend.

He died in Washington on December 24, 1824, of the croup in the 60th year of his age. Among his last words were the following "When I am gone let the big guns be fired over me."

The National Intelligencer reported on December 28, 1824, on his death:

At Tennison's Hotel, on Friday last, the 24th instant, Pooshamataha, a Chief of the Choctaw Nation of Indians, distinguished for his bold elocution and his attachment to the United States. At the commencement of the late war on our Southern border, he took an early and decided stand in favor of the weak and isolated settlements on Tombigby, and he continued to fight with and for them whilst they had an enemy in the field. His bones will rest a distance from his home, but in the bosom of the people he delighted to love. May a good hunting ground await his generous spirit in another and a better world. Military honors were paid to his remains by the Marine Corps of the United States, and by several uniformed companies of the militia.

The Hampshire Gazette (MA), Jan. 5, 1825, reported:

At Washington city, PUSHA-A-MA-TA-HA, principal chief of a district of the Choctaw nation of Indians. This chief was remarkable for his personal courage and skill in war, having been engaged in 24 battles, several of which were fought under the command of Gen. Jackson.

Successors

There is a six-month period in which no documentation of the Chief of the Six Towns is recorded; however, Tappenahoma, nephew of Chief Pushmataha'[1] is shown to have succeeded Pushmataha. Correspondence dated June 1825 lists Tappenahoma in this position. Several Choctaw histories have confused Tappenahoma with General Hummingbird, who died at the age of 75 on December 23, 1827.[16] A letter dated September 28, 1828, from Tappenahoma mentions his Uncle Pushmataha. The Choctaw nation at this time was on the point of Civil War; the faction supported by David Folsom elected John Garland to replace Tappenahoma by October 11, 1828.[1] Nittakechi (Day-prolonger) succeeded Humming Bird and was the Chief for the District during the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek.[17]

Legacy and honors

- The Choctaw Nation in Oklahoma included a Pushmataha District, where his Tribe settled, until Oklahoma's statehood.

- The new state of Oklahoma named Pushmataha County in his honor.

- The Boy Scouts of America named the council containing the area of Nanih Waiya, the "Pushmataha Area Council". The story of Pushmataha is related to all Scouts at the local summer camp.

- Camp Pushmataha in Citronelle, AL is owned by the City of Citronelle is the old Boy Scout Camp for the Mobile Area Council and is the site Last Surrender of the Civil War.

- The community of Pushmataha in northwestern Choctaw County, Alabama, is named in his honor. The area was formerly part of traditional Choctaw territory in west-central Alabama prior to the removal, following the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek.[18]

- Pushmataha Landing in Coahoma County, Mississippi[19]

- At least three ships have borne the name Pushmataha. A British-flagged sloop serving Confederate commercial interests during the American Civil War was known as Pushmataha, and two U.S. Navy vessels have also borne the name. The first USS Pushmataha was a screw sloop built in 1868 and soon renamed USS Congress. The second USS Pushmataha was a Natick-class tugboat launched in 1974, struck from the Navy list in 1995.

Family

Many historians use a quote attributed to Gideon Lincecum, who said that Pushmataha was an orphan with no family; but, both George Strother Gaines and Henry Sales Halbert mention his family. In Publications of the Mississippi Historical Society, Vol 6, Halbert mentions a sister named Nahomtima, the mother of Tappenahoma and Oka Lah Homma (from his notes). Gaines mentions the nephew who succeeded Pushmataha, but does not give a name.[20] Halbert received his information from first and secondhand accounts, and Gaines from personal knowledge. Although Lincecum lived among the Choctaw, he writes that he only met the Chief on three or four occasions, while living near the Chief Mosholatubbee. Most of what Gideon Lincecum wrote came from information provided by others.

The supplement to the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek mentions the widows of Pushmataha. Only one widow has been documented as having received the land guaranteed to them by the treaty. When she and her three children later sold the land, her name was recorded in three different spellings in the deed: as Immahoka, Lunnabaka/Lunnabaga, and Jamesaichikkako. [21] Some individuals claim to be descendants of the chief, but the only record of the number of his children is by Charles Lanman,[22] who wrote there were five. Lanman likely based his statement on the notes of Thompson Mckinney, who had resided among the Choctaw for many years. Mckinney had written in an 1830 letter to James L. McDonald, a Choctaw lawyer in Hinds County, Mississippi, about his interest in writing about Pushmataha.

Alabama Congressional papers of November 1818 referred to a son.[23] His children were:

- Hashitubbiee, also known as Johnson Pushmataha, died 1862–1865 in Blue County, Choctaw Nation, 3rd District

- Betsy Moore, nothing found after deed

- Martha Moore, nothing found after deed

- James Madison, disappeared after the 1818 record in Alabama papers

- Running Deer, also known as "Julia Ann", born about 1780 in what is now Perry County, Mississippi. She married Joseph “Jack” Anderson and they had seven children before her death in 1810. She is buried in Lamar County, Mississippi in a privately owned cemetery.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 [NARA, letter transcriptions found show the date of death listed by Mr. Hudson is incorrect. A letter to Washington in 1834, written by Pierre Juzan, says that he is the agent for the family of Tappenahomah now deceased, and he is asking for a patent for the two sections of land located for Tappenahomah at the time of the treaty by Col. Martin. A letter by David Folsom to Thomas McKinney relates to distributions of $6,000 for something. He says he does not have faith in Chief Tapenahumma. "I have not strong confidence in his doing it faithfully if it were placed entirely at has disposal." Another letter by David Folsom refers to the "unmoral conduct and intemperance of the Chief Tapennahomma of the South Dis has been broke of his office", dated October 11, 1828. John Garland replaced Tapennahoma. 28 Sept 1828 to Sec of War I am now in my friend Col. Wards House on my way to see the country pointed out to my nation by your friend Col. McKinney last year. I go to see the country because it is my great fathers request I am chief of the Southern District of this nation in place of my uncle Pushmattahaw whose bones lyes below this earth near your residence. And which I trust his spirit is in a better world than this as you know as well as I that this is a place of continual trouble ... ... "Taphemhoma 5 July 1829 Uncle Tahpemaloomah has fully made up his mind to emigrate to the west of mississippi (looks like 100 will accompany him.) ..... ..... ... ... He would like to start by the 29 of October. I should like to go as an interpreter and I wish you to write to the Sec of war for the appointment for me. Respectfully your friend Pierre Juzan]

- 1 2 3 Swanton, John (1931). "Source Material for the Social and Ceremonial Life of the Choctaw Indians". Smithsonian Institution Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin (103).

- ↑ Handbook of American Indians, 1906

- 1 2 3 4 Pack, Ellen. "Pushmataha Great Choctaw Chief". Retrieved November 29, 2006.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Pushmataha, Choctaw Indian Chief". Access Genealogy: Indian Tribal Records. Retrieved November 29, 2006.

- 1 2 Lincecum, Gideon (1906). "Life of Apushimataha". Mississippi Historical Society Publications. 9: 415–485.

- ↑ O'Brien, Greg (1999). "Protecting Trade through War: Choctaw Elites and British Occupation of the Floridas". In Martin Daunton and Rick Halpern (ed.). Empire and Others: British Encounters with Indigenous Peoples, 1600–1850. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 149–166.

- 1 2 3 4 Jones, Charlie; Mike Bouch (November 1987). "Sharing Choctaw History". Bishinik. University of Minnesota. Archived from the original on January 23, 2007. Retrieved November 29, 2006.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 O'Brien, Greg (2004). "Pushmataha: Choctaw Warrior, Diplomat, and Chief". Mississippi History NOW. Mississippi Historical Society. Archived from the original on September 25, 2006. Retrieved November 29, 2006.

- ↑ "Pushmataha". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 2006. Retrieved November 29, 2006.

- ↑ Turner III, Frederick (1978) [1973]. "Poetry and Oratory". The Portable North American Indian Reader. Penguin Book. pp. 246–247. ISBN 0-14-015077-3.

- ↑ Junaluska, Arthur; Vine Deloria, Jr. (1976). "Chief Pushmataha – Response to Tecumseh" (mp3). Great American Indian Speeches, Vol. 1 (Phonographic Disc). Caedmon. Retrieved November 29, 2006.

- 1 2 Lossing, Benson J. (1869). "XXXIV: War Against the Creek Indians.". Pictorial Field-Book of the War of 1812. New York: Harper & Brothers. Retrieved November 30, 2006.

- 1 2 White, Earl. "Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma". Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma. Archived from the original on September 13, 2009. Retrieved February 5, 2008.

- ↑ William Jennings Bryan, ed. (1906). "Pushmataha to John C. Calhoun". The World's Famous Orations: vol. VIII – America: I (1761–1837). Retrieved November 29, 2006.

- ↑ [Commercial Advertisor, February 13, 1828, published, "At his residence near the Choctaw Agency, December 23rd last, General Hummingbird, Choctaw Chief, at the advanced age of 75 ...". Source found on www.genealogybank.com, historical newspapers collection. Also found in other newspapers]

- ↑ Peter James Hudson (March 1939). "Chronicles of Oklahoma". Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma. Archived from the original on July 5, 2008. Retrieved August 14, 2008.

- ↑ Greg O'Brien (February 6, 2011). "Pushmataha". The Encyclopedia of Alabama. Auburn University. Retrieved July 23, 2011.

- ↑ Baca, Keith A. (2007). Native American Place Names in Mississippi. University Press of Mississippi. pp. 87–88. ISBN 978-1-60473-483-6.

- ↑ Society, Mississippi Historical (July 11, 2017). "Publications of the Mississippi Historical Society". Retrieved July 11, 2017 – via Google Books.

- ↑ [Holmes County Deeds, book A, p 37]

- ↑ Lanman, Charles. "Pushmatahaw". Appletons' Journal: A Magazine of General Literature. Retrieved July 11, 2017.

- ↑ "House Journal 1818 2nd Session Nov 16". Archived from the original on June 13, 2011. Retrieved July 5, 2012., Alabama State papers

Further reading

- James Taylor Carson, Searching for the Bright Path: The Mississippi Choctaws from Prehistory to Removal (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1999).

- H. B. Cushman, History of the Choctaw, Chickasaw, and Natchez Indians (originally published 1899; reprinted Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press, 1999).

- Clara Sue Kidwell, Choctaws and Missionaries in Mississippi, 1818–1918 (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1995).

- Greg O'Brien, Choctaws in a Revolutionary Age, 1750–1830 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2005).

- Richard White,The Roots of Dependency: Subsistence, Environment, and Social Change among the Choctaws, Pawnees, and Navajos (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1983).