| Prince of Persia | |

|---|---|

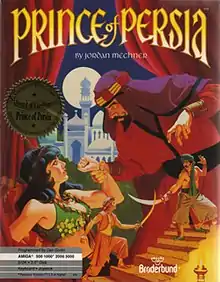

Original cover art used for the home computer versions in the West. | |

| Developer(s) | Broderbund Ports

|

| Publisher(s) | Broderbund Ports

|

| Designer(s) | Jordan Mechner |

| Composer(s) | Francis Mechner (music) Tom Rettig (sound) Mark Cooksey (NES) |

| Platform(s) | Apple II (see Ports) |

| Release | |

| Genre(s) | Cinematic platformer |

| Mode(s) | Single-player |

Prince of Persia is a cinematic platform game developed and published by Broderbund for the Apple II in 1989. It was designed and implemented by Jordan Mechner. Taking place in medieval Persia, players control an unnamed protagonist who must venture through a series of dungeons to defeat the evil Grand Vizier Jaffar and save an imprisoned princess.

Much like Karateka, Mechner's first video game, Prince of Persia used rotoscoping for its fluid and realistic animation. For this process, Mechner used as reference for the characters' movements videos of his brother doing acrobatic stunts in white clothes[4] and swashbuckler films such as The Adventures of Robin Hood.

The game was critically acclaimed and, while not an immediate commercial success, sold many copies as it was ported to a wide range of platforms after the original Apple II release. It is believed to have been the first cinematic platformer and inspired many games in this subgenre, such as Another World.[5] Its success launched the Prince of Persia franchise, consisting of two sequels, Prince of Persia 2: The Shadow and the Flame (1993) and Prince of Persia 3D (1999), and two reboots: Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time (2003), which was followed by three sequels of its own, and Prince of Persia (2008).

Gameplay

The main objective of the player is to lead the unnamed protagonist out of dungeons and into a fortress tower before time runs out. This cannot be done without bypassing traps and fighting hostile swordsmen. The game consists of twelve levels (though some console versions have more). However, a game session may be saved and resumed at a later time only after level 2.

The player has a health indicator that consists of a series of small red triangles. The player starts with three. Each time the protagonist is damaged (cut by sword, fallen from two floors of heights or hit by a falling rock), the player loses one of these indicators. There are small jars containing potions of several colours and sizes. The red potions scattered throughout the game restore one health indicator. The blue potions are poisonous, and they take one life indicator as damage. There are also large jars of red potion that increase the maximum number of health indicators by one, and large jars of green potion that grants a temporarily ability to hover. If the player's health is reduced to zero, the protagonist dies. Subsequently, the game is restarted from the beginning of the stage in which the protagonist died but the timer will not reset to that point, effectively constituting a time penalty. There is no counter for the number of lives, but if time runs out, the princess will be gone and the game will be over, subject to variations per console versions:

- The DOS version allows the player already in the very late part of Level 12 to continue after time is out with no extra life, so:

- Restarting the level by pressing appropriate buttons is not death, thus not failing the game yet.

- Any player's death, including having killed Jaffar then falling from excessive floors of heights, also fails the game in which case the Princess is also gone.

- Only defeating Jaffar and exiting Level 12 alive will still save the Princess, with a negative time score in the hall of fame.

- The Macintosh port will not give the player a game over once they reach the final area of Level 12 (stored in data as Level 13), provided they make it there on time. The player must cross the magic bridge and make a screen-transition to a room with falling tiles to be 'safe'; once there, they will always be allowed to continue, regardless of deaths or time expiration. Running out of time at any point before the screen-transition, including the bridge, will result in game over as usual.

- The Super NES remake allows the players to save themselves after time is out, to get the game over at the end without the princess saved.

There are three types of traps that the player must bypass: spike traps, deep pits (three or more levels deep) and guillotines. Getting caught or falling into each results in the instant death of the protagonist. In addition, there are gates that can be raised for a short period of time by having the protagonist stand on the activation trigger. The player must pass through the gates while they are still open, avoiding locking triggers. Sometimes, there are various traps between an unlock trigger and a gate.

Hostile swordsmen (Jaffar and his guards) are yet another obstacle. The player obtains a sword in the first stage, which they can use to fight these adversaries. The protagonist's sword maneuvers are as follows: advance, back off, slash, parry, or a combined parry-then-slash attack. Enemy swordsmen also have a health indicator similar to that of the protagonist. Killing them involves slashing them until their health indicator is depleted or by pushing them into traps while fighting.

In stage three a skeletal swordsman comes to life and does battle with the protagonist. The skeleton cannot be killed with the sword, but it can be defeated by being dropped into one of the pits.

A unique trap encountered in stage four, which serves as a plot device, is a magic mirror, whose appearance is followed by an ominous leitmotif. The protagonist is forced to jump through this mirror upon which his doppelganger emerges from the other side, draining the protagonist's health to one. This apparition later hinders the protagonist by stealing a potion and throwing him into a dungeon. The protagonist cannot kill this apparition as they share lives; any damage inflicted upon one also hurts the other. Therefore, the protagonist must merge with his doppelganger.

In stage eight, the protagonist becomes trapped behind a gate before he can reach the exit. In this stage the Princess sends a white mouse to trigger the gate open again, allowing him to proceed to the next level.

In stage twelve protagonist faces his shadow doppelgänger. Once they have merged, the player can run across an invisible bridge to a new area, where they battle Jaffar (once the final checkpoint is reached, the player will no longer get a game over screen even if time runs out, except if the player dies after the timeout). Once Jaffar is defeated, his spell is broken and the Princess can be saved. In addition, the in-game timer is stopped at the moment of Jaffar's death, and the time remaining will appear on the high scores.

Plot

The game is set in medieval Persia. While the sultan is fighting a war in a foreign land, his vizier Jaffar, a wizard, seizes power. His only obstacle to the throne is the Sultan's daughter. Jaffar locks her in a tower and orders her to become his wife, or she would die within 60 minutes (extended to 120 minutes in the Super NES version, which has longer and harder levels). The game's unnamed protagonist, whom the Princess loves, is thrown prisoner into the palace dungeons. In order to free her, he must escape the dungeons, get to the palace tower and defeat Jaffar before time runs out. In addition to guards, various traps and dungeons, the protagonist is further hindered by his own doppelgänger, conjured out of a magic mirror.

Development

Development for the game began in 1985, the year Jordan Mechner graduated from Yale University. At that time, Mechner had already developed one game, Karateka, for distributor Broderbund. Despite expecting a sequel to Karateka, the distributor gave Mechner creative freedom to create an original game.[6] The game drew from several sources of inspiration beyond video games, including literature such as the Arabian Nights stories,[7] and films such as Raiders of the Lost Ark[8] and The Adventures of Robin Hood.[9]

For a few seconds, the camera angle has them in exact profile. This was a godsend. I did my VHS/one-hour-photo rotoscope procedure, spread two-dozen snapshots out on the floor of the office and spent days poring over them trying to figure out what exactly was going on in that duel, how to conceptualise it into a repeatable pattern.

Jordan Mechner on how he used the final duel between Errol Flynn and Basil Rathbone from The Adventures of Robin Hood to create the game's swordfighting mechanic.[6]

Prince of Persia was programmed in 6502 assembly, a low-level programming language.[10] Mechner used an animation technique called rotoscoping, with which he used footage to animate the characters' sprites and movements. To create the protagonist's platforming motions, Mechner traced video footage of his younger brother running and jumping in white clothes.[11] To create the game's sword fighting sprites, Mechner rotoscoped the final duel scene between Errol Flynn and Basil Rathbone in the 1938 film The Adventures of Robin Hood.[9] Though the use of rotoscoping was regarded as a pioneering move, Mechner later recalled that "when we made that decision with Prince of Persia, I wasn't thinking about being cutting edge—we did it essentially because I'm not that good at drawing or animation, and it was the only way I could think of to get lifelike movement".[12] Also unusual was the method of combat: protagonist and enemies fought with swords, not projectile weapons, as was the case in most contemporary games. Mechner has said that when he started programming, the first ten minutes of the film Raiders of the Lost Ark had been one of the main inspirations for the character's acrobatic responses in a dangerous environment.[13]

During development, the Prince was meant to be a nonviolent character, so the game didn't initially include combat. However, due to finding the gameplay to be dull and after incessant demand from Tomi Pierce, a colleague of his, Mechner added sword fighting to the game and created Shadow Man, the Prince's doppelgänger. Guards were later added when Mechner managed to make use of an additional 12K of the Apple II's memory.[14]

For the Japanese computer ports, Arsys Software[15] and Riverhillsoft[2] enhanced the visuals and redesigned the Prince's appearance, introducing the classic turban and vest look. This version became the basis for the Macintosh version and later Prince of Persia ports and games by Broderbund. Riverhillsoft's FM Towns version also added a Red Book CD audio soundtrack.[2]

The Game Boy version was the first game to feature music by Tommy Tallarico. He was a playtester for Virgin Interactive and offered to compose the music free of charge.

Ports

After its release on the Apple II, Prince of Persia was ported to a variety of platforms. Below is a list of the ports that were developed.

Official | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Port | Release | Developer | Publisher |

| NEC PC-9801 | July 1990[2] | Arsys Software[15] | Riverhillsoft |

| DOS | September 1990 | Broderbund | |

| Amiga | October 1990 December 1990 (EU)[16] |

Domark | |

| Atari ST | March 1991[17] | Broderbund | |

| Sharp X68000 | April 30, 1991 | Riverhillsoft | |

| Amstrad CPC | July 1991 | Broderbund | |

| SAM Coupé | August 1991 | Chris 'Persil' White[18] | Revelation |

| TurboGrafx-16 | November 8, 1991 | Riverhillsoft | |

| Game Boy | January 1992 | Virgin Games | |

| FM Towns | June 1992 | Riverhillsoft | |

| Master System | June 1992[19] | Domark | |

| Super NES | July 3, 1992 (JP) November 1, 1992 (US, EU) |

Arsys Software[20] | Masaya (JP) Konami (US, EU) |

| Sega CD | August 7, 1992 (JP) 1992 (US) April 2, 1993 (EU)[21] |

Bits Laboratory | Victor Musical Industries (JP) Sega (US, EU) |

| NES | November 2, 1992 | MotiveTime | Virgin Games |

| Macintosh | December 1992 | Presage Software development, Inc. | |

| Game Gear | January 1993 | Domark | |

| Genesis | February 1994 | Domark (EU) Tengen (US) | |

| Game Boy Color | April 15, 1999 | Ed Magnin and Associates[22] | Red Orb Entertainment[22] |

| Mobile ("Classic") | 2007 | Gameloft | |

| Xbox 360 ("Classic") | June 13, 2007 | Gameloft | Ubisoft |

| PlayStation 3 ("Classic") | October 23, 2008 | ||

| Blackberry ("Classic") | April 7, 2009 | Gameloft | |

| iOS ("Retro", replaced by "Classic" version in 2011) | May 28, 2010 | Ubisoft | |

| iOS ("Classic") | December 19, 2011 | ||

| Nintendo 3DS (Game Boy Color version on Virtual Console) | January 19, 2012[23] | ||

| Wii (Super NES version on Virtual Console) | January 19, 2012[23] | ||

| Android ("Classic") | September 13, 2012 | Ubisoft Pune | Ubisoft |

Unofficial | |||

| Port | Release | Developer | Publisher |

| Electronika BK-0011M | 1994 | Evgeny Pashigorov, Pasha Sizykh[24] | Flame Association |

| ATM Turbo | 1994 | Honey Soft, Andrey Honichem | Moscow |

| ZX Spectrum | 1996 | Nicodim[25] | Magic Soft [25] MC Software [26] |

| HP48/GX | 1998 | Iki[27] | |

| TI-89, TI-92 | 2003 | David Coz[28] | |

| Enterprise 128 | 2006 | Geco (Noel Persa)[29][30] | |

| Commodore Plus/4 (Demo) | 2007 | GFW & ACW[31] | |

| Commodore 64 | 2011 | Andreas Varga[32][33] | |

| Linux, macOS, Microsoft Windows | 2014 | Dávid Nagy. This port, called SDLPoP, uses SDL.[34] | |

| Roku (Streaming Box and Smart TV) | 2016 | Marcelo Lv Cabral[35][36] | |

| BBC Master | 2018 | Kieran[37] | |

| Atari XE | 2021 | rensoup[38] | |

| JavaScript | 2022 | Oliver Klemenz[39][40] | |

Reception

| Publication | Score | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DOS | Macintosh | Master System | PC | Sega Genesis | SNES | |

| Dragon | ||||||

| Electronic Gaming Monthly | 32/40[42] | |||||

| Génération 4 | 90%[3] | |||||

| Adventure Classic Gaming | ||||||

| Bad Influence! | ||||||

| MacWorld | ||||||

| Mean Machines | 91%[19] | |||||

| Mega Guide | Positive[46] | |||||

| MegaTech | 82%[47] | |||||

| Sega Force | 94%[48] | |||||

| Publication | Award |

|---|---|

| MacUser | 1992 Eddy Award[49] |

| TILT! | 1992 Tilt d'Or[49] |

Prince of Persia received a positive critical reception, but was initially a commercial failure in North America, where it had sold only 7,000 units each on the Apple II and IBM PC by July 1990. It was when the game was released in Japan and Europe that year that it became a commercial success. In July 1990, the NEC PC-9801 version sold 10,000 units as soon as it was released in Japan. It was then ported to various different home computers and video game consoles, eventually selling 2 million units worldwide by the time its sequel Prince of Persia 2: The Shadow and the Flame (1993) was in production.[2][50][51]

Charles Ardai of Computer Gaming World wrote that the game package's claim that it "breaks new ground with animation so uncannily human it must be seen to be believed" was true. He wrote that Prince of Persia "succeeds at being more than a running-jumping game (in other words, a gussied-up Nintendo game)" because it "captures the feel of those great old adventure films", citing Thief of Baghdad, Frankenstein, and Dracula. Ardai concluded that it was "a tremendous achievement" in games comparable to that of Star Wars in film.[52]

In 1991, the game was ranked the 12th best Amiga game of all time by Amiga Power.[53] In 1992, The New York Times described the Macintosh version as having "brilliant" graphics and "excellent" sound.[54] Reviewing the Genesis version, GamePro praised the "extremely fluid" animation of the player character and commented that the controls are difficult to master but nonetheless very effective. Comparing it to the Super NES version, they summarized that "the Genesis version has better graphics, and the SNES has better music. Otherwise, the two are identical in almost every way ..."[55] Electronic Gaming Monthly (EGM) likewise assessed the Genesis version as "an excellent conversion of the classic action game", and added that the game's challenging strategy and technique give it high longevity.[56] EGM's panel of four reviewers each gave it a rating of 8 out of 10, adding up to an overall score of 32 out of 40.[42]

In 1991, PC Format named Prince of Persia one of the 50 best computer games ever, highlighting its "unbelievably good animation".[57] In 1996, Computer Gaming World named Prince of Persia the 84th best game ever, with the editors calling it "an acrobatic platformer with amazingly fluid action".[58] In 1995, Flux ranked the game 42nd on their Top 100 Video Games.[59]

Legacy

Prince of Persia influenced cinematic platformers such as Another World and Flashback as well as action-adventure games such as Tomb Raider,[2] which used a similar control scheme.[60] A few DOS games were created using exactly the same game mechanics of the DOS version of Prince of Persia. Makh-Shevet created Cruel World in 1993 and Capstone Software created Zorro in 1995.[61]

Prince of Persia was remade and ported by Gameloft. The remake, titled Prince of Persia Classic, was released on June 13, 2007, to the Xbox Live Arcade, and on October 23, 2008, on the PlayStation Network. It features the same level design and general premise but contained 3D-rendered graphics, more fluid movements, and Sands of Time aesthetics.[62] The gameplay and controls were slightly adjusted to include a wall-jump move and different swordplay. New game modes were also added, such as "Time Attack" and "Survival".[63] The game has also been released on Android.[64]

Reverse engineering efforts by fans of the original game have resulted in detailed documentation of the file formats of the MS-DOS version.[65] Various level editors have been created that can be used to modify the level files of the game.[66] With these editors and other software, over 60 mods have been created.[67]

In April 2012, Jordan Mechner established a GitHub repository[68] containing the long-thought-lost[69] original Apple II source code for Prince of Persia.[70][71] A technical document describing the operation of this source code is available on Mechner's website.[72]

In April 2020, Mechner did an AMA on Reddit where he stated that he would be releasing his journals from the development of the game as a book and users could ask any questions that they may have about the game to him.[73]

References

- ↑ Mechner, Jordan (May 3, 2009). "Prince of Persia released". jordanmechner.com. Archived from the original on December 12, 2009. Retrieved December 13, 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Kurt Kalata; Sam Derboo (August 12, 2011). "Prince of Persia". Hardcore Gaming 101. Archived from the original on May 1, 2015. Retrieved June 22, 2012.

- 1 2 Prince of Persia review Archived May 9, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, Generation 4, issue #25, September 1990

- ↑ "Prince of Persia's Groundbreaking Character Animations Started Life in a High School Parking Lot". Gizmodo. April 1, 2020. Retrieved October 31, 2023.

- ↑ Rybicki, Joe (May 5, 2008). "Prince of Persia Retrospective". GameTap. Turner Broadcasting System. Archived from the original on May 9, 2008. Retrieved March 7, 2014.

- 1 2 "The Making Of: Prince Of Persia". Edge. Future plc. Archived from the original on July 10, 2013. Retrieved October 11, 2015.

{{cite magazine}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ↑ Rus McLaughlin; Scott Collura & Levi Buchanan (May 18, 2010). "IGN Presents: The History of Prince of Persia (page 1)". IGN. Archived from the original on December 3, 2014. Retrieved June 28, 2013.

- ↑ Gamasutra - Features - Game Design: Theory & Practice Second Edition: 'Interview with Jordan Mechner' Archived December 19, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- 1 2 Mechner, Jordan (2011). Classic Game Postmortem: PRINCE OF PERSIA (Speech). Game Developers Conference. San Francisco, California. Event occurs at 38:35. Archived from the original on June 1, 2013. Retrieved May 30, 2013.

- ↑ Caoili, Eric (April 17, 2012). "Prince of Persia 's once-lost source code released". Gamasutra. Retrieved August 29, 2020.

- ↑ October 20, 1985 | jordanmechner.com Archived August 5, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "An Interview with Jordan Mechner". Next Generation. No. 25. Imagine Media. January 1997. p. 108.

- ↑ Gamasutra - Features - Game Design: Theory & Practice Second Edition: 'Interview with Jordan Mechner' Archived December 19, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Mechner, Jordan (March 17, 2020). "How Prince of Persia Defeated Apple II's Memory Limitations | War Stories | Ars Technica". YouTube. 10 minutes in. Retrieved October 25, 2020.

- 1 2 Prince of Persia release info Archived October 6, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, Moby Games, October 3, 1989

- ↑ "More Than Fit For A Prince". The One. No. 27. emap Images. December 1990. p. 16.

- ↑ "Prince of Persia". Atari ST User. March 1991. Retrieved March 21, 2019.

- ↑ "SAM Coupe Magazine Preview". February 1992: 50. Retrieved March 3, 2016.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - 1 2 "Prince of Persia - Sega Review" (PDF). Mean Machines. No. 22 (July 1992). June 27, 1992. p. 90. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 3, 2014. Retrieved September 9, 2021.

- ↑ "Corporate profile". Cyberhead. Archived from the original on October 24, 2001. Retrieved August 30, 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ↑ "News: Mega CD Launches!". Computer and Video Games. No. 138. United Kingdom. May 1993. p. 8.

- 1 2 "Prince of Persia International Releases". Giant Bomb. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved June 17, 2013.

- 1 2 "RELIVE CLASSIC PRINCE OF PERSIA ON WII™ AND 3DS™". MCV. January 19, 2012. Archived from the original on January 15, 2014. Retrieved June 17, 2013.

- ↑ "Prince of Persia BK-0011M". R-GAMES.NET. Archived from the original on December 1, 2014. Retrieved October 15, 2014.

- 1 2 Tarján, Richárd (February 21, 2009). "Prince of Persia - ZX Spectrum version (Nicodim/Magic Soft, 1996)" (DOC). World of Spectrum. Retrieved June 16, 2013.

- ↑ Ribic, Samir (July 2007). "ZX Spectrum Screenshot Catalog": 655.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ "Detailed information for Iki's Prince of Persia". hpcalc.org. October 30, 1998. Archived from the original on October 26, 2015. Retrieved October 17, 2016.

- ↑ "Prince of Persia - TI Series". September 20, 2003. Archived from the original on December 22, 2015. Retrieved October 15, 2015.

- ↑ Kiss, László (2018). "What you should definitely see" (PDF). ENTERPRESS. Hungary. p. 21. Retrieved April 15, 2020.

- ↑ Persa, Noel (June 15, 2006). "Prince of Persia". Enterprise Forever. Retrieved April 15, 2020.

- ↑ "Prince of Persia". Plus 4 World. Archived from the original on February 22, 2014. Retrieved February 5, 2014.

- ↑ Lemon, Kim. "Prince of Persia". Lemon. Retrieved June 16, 2013.

- ↑ "Prince of Persia C64 - Development Blog". March 2, 2012. Archived from the original on December 11, 2016. Retrieved April 6, 2017.

- ↑ "Get the Games: SDLPoP". PoPOT Modding Community. Archived from the original on October 18, 2014. Retrieved October 12, 2014.

- ↑ "lvcabral/Prince-of-Persia-Roku". GitHub. Retrieved June 16, 2016.

- ↑ "PoP1 for Roku Set-Top Box - Prince of Persia". forum.princed.org. Archived from the original on October 9, 2016. Retrieved June 16, 2016.

- ↑ Connell, Kieran. "Prince of Persia". Bitshifters. Archived from the original on April 1, 2018. Retrieved April 3, 2018.

- ↑ "Unicorns season: Prince of Persia for the A8!". November 26, 2019.

- ↑ "You Can Play the Original 'Prince of Persia' on Your Apple Watch, No App Required". Gizmodo. January 12, 2022. Retrieved October 31, 2023.

- ↑ "PrinceJS". princejs.com. Retrieved October 31, 2023.

- ↑ Lesser, Hartley; Lesser, Patricia & Lesser, Kirk (December 1992). "The Role of Computers" (PDF). Dragon (188): 57–64. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 21, 2016.

- 1 2 Electronic Gaming Monthly, 1998 Video Game Buyer's Guide, p. 86

- ↑ "Prince of Persia Review". Jeremiah Kauffman. February 19, 2006. Archived from the original on January 21, 2013. Retrieved February 21, 2013.

- ↑ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: "Main Review: Prince of Persia (SNES)". Bad Influence!. Series 1. Episode 10. January 14, 1993. Event occurs at 5:08. ITV. CITV. Retrieved October 14, 2021.

- ↑ Steven A. Schwartz (September 1992). "MacWorld 9209" (9209): 292. Retrieved December 1, 2017.

You'll be amazed by Prince of Persia.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Gregory, Mark, ed. (November 28, 1992). "Persia Hits the Master System". Mega Guide. p. 2.

- ↑ "Game Index". MegaTech. No. 42 (June 1995). May 31, 1995. pp. 30–1.

- ↑ "Sega Force Issue 7" (7). July 1992: 13. Archived from the original on August 23, 2016. Retrieved July 9, 2016.

The best MS game we've seen for ages!

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - 1 2 Castro, Radford (October 25, 2004). Let Me Play: Stories of Gaming and Emulation. Hats Off Books. p. 218. ISBN 978-1587363498. Retrieved December 1, 2017.

- ↑ Pullin, Keith (December 1999). "Prince of Persia 3D". PC Zone (83): 91.

- ↑ Saltzman, Marc (May 18, 2000). Game Design: Secrets of the Sages, Second Edition. Brady Games. pp. 410, 411. ISBN 1566869870.

- ↑ Ardai, Charles (December 1989). "Good Knight, Sweet Prince". Computer Gaming World. No. 66. pp. 48 & 64. Archived from the original on May 10, 2013. Retrieved November 4, 2013.

- ↑ "All-Time Top 100 Games". Amiga Power magazine. Future Publishing. May 1991. p. 6. Archived from the original on January 4, 2012. Retrieved May 30, 2013.

- ↑ Shannon, L. R. (August 11, 1992). "Playing at War, Once Removed". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 15, 2014. Retrieved July 5, 2014.

- ↑ "ProReview: Prince of Persia". GamePro. No. 67. IDG. April 1994. p. 30.

- ↑ "Review Crew: Prince of Persia". Electronic Gaming Monthly. No. 56. Sendai Publishing. March 1994. p. 38.

- ↑ Staff (October 1991). "The 50 best games EVER!". PC Format (1): 109–111.

- ↑ "150 Best Games of All Time". Computer Gaming World. November 1996. pp. 64–80. Archived from the original on April 8, 2016. Retrieved March 25, 2016.

- ↑ "Top 100 Video Games". Flux. Harris Publications (4): 30. April 1995.

- ↑ Blache, Fabian & Fielder, Lauren, History of Tomb Raider, GameSpot, Accessed April 1, 2009

- ↑ "Zorro". RGB Classic Games. Archived from the original on September 10, 2015. Retrieved October 11, 2015.

- ↑ Review of Prince of Persia remake by Nick Suttner, June 13, 2007, 1Up.com

- ↑ "Xboxic Classic review". Xboxic. Archived from the original on December 6, 2008.

- ↑ "Prince of Persia Classic". Ubisoft/Google. Archived from the original on May 22, 2013.

- ↑ "Prince of Persia Specifications of File Formats" (PDF). Princed Development Team. January 5, 2008. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 2, 2011. Retrieved May 7, 2011.

- ↑ "Modding Community; Level Editors". PoPOT.org. Archived from the original on December 7, 2011. Retrieved May 7, 2011.

- ↑ "Modding Community; Custom Levels". PoPOT.org. Archived from the original on December 6, 2011. Retrieved May 7, 2011.

- ↑ Prince of Persia Apple II Archived December 30, 2012, at the Wayback Machine on github.com/jmechner

- ↑ Ciolek, Todd (October 17, 2012). "Among the Missing: Notable Games Lost to Time". 1up.com. Archived from the original on October 26, 2015. Retrieved June 19, 2015.

Prince of Persia creator Jordan Mechner believed that the source code to the game's original Apple II version was gone when he failed to find it in 2002. Ten years later, Mechner's father uncovered a box of old games at the family home, and among them were disks containing Prince of Persia's bedrock program.

- ↑ Fletcher, JC (April 17, 2012). "Prince of Persia source code successfully rescued". joystiq.com. Archived from the original on October 27, 2012. Retrieved December 23, 2012.

- ↑ Mastrapa, Gus (April 20, 2012). "The Geeks Who Saved Prince of Persia's Source Code From Digital Death". Wired. Archived from the original on December 8, 2012. Retrieved December 23, 2012.

- ↑ Mechner, Jordan (October 12, 1989). "Prince of Persia Technical Information" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on October 6, 2014. Retrieved October 6, 2014.

- ↑ "I'm Jordan Mechner. Thirty years ago, I made a game called Prince of Persia. Now I'm releasing my 1980s game-dev journals as a book. AMA!". April 30, 2020.

External links

- Prince of Persia on game designer Jordan Mechner's official website

- Prince of Persia at MobyGames

- Prince of Persia can be played for free in the browser at the Internet Archive

- Prince of Persia 1 page at PoPUW.com

- How Prince of Persia Defeated Apple II's Memory Limitations on YouTube