| Posterior spinal artery syndrome | |

|---|---|

| |

| 5: posterior spinal arteries |

Posterior spinal artery syndrome (PSAS), also known as posterior spinal cord syndrome, is a type of incomplete spinal cord injury.[1] PSAS is the least commonly occurring of the six clinical spinal cord injury syndromes, with an incidence rate of less than 1%.

PSAS originates from an infarct in the posterior spinal artery and is caused by lesions on the posterior portion of the spinal cord, specifically the posterior column, posterior horn, and posterolateral region of the lateral column.[2] These lesions can be caused by trauma to the neck, occlusion of the spinal artery, tumors, disc compression, vitamin B12 deficiency, syphilis, or multiple sclerosis.[3] Despite these numerous pathological pathways, the result is an interruption in transmission of sensory information and motor commands from the brain to the periphery.

Causes

Trauma to the spinal cord, such as neck hyperflexion injuries, are often the result of car accidents or sports-related injuries. In such injuries, posterior dislocations and extensions occur without the rupture of ligaments. This blunt trauma may be further complicated with subsequent disc compression. In addition to these complications, transient ischemic attacks could occur in the spinal cord during spinal artery occlusion.[4]

Common pathological sources of PSAS include Friedreich's Ataxia, an autosomal-recessive inherited disease, and tumors such as astrocytoma, ependymoma, meningioma, neurofibroma, sarcoma, and schwannoma.

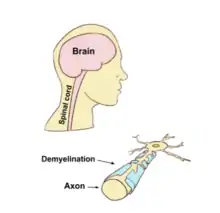

Cobalamin, commonly known as vitamin B12, plays a crucial role in the synthesis and maintenance of myelin in neurons found in the spinal cord. A deficiency of this essential vitamin results in demyelination, a deterioration of the axon's layer of insulation causing interrupted signal transmission, with a currently unknown specificity to the posterior region.[5]

PSAS may develop with the failure to treat syphilis. Symptoms typically appear during the tertiary phase of the disease, between twenty and thirty years after the initial syphilis infection. Failure to treat syphilis leads to progressive degeneration of the nerve roots and posterior columns. The bacteria Treponema pallidum that causes syphilis results in locomotor ataxia and tabes dorsalis. Further complications from tabes dorsalis include optic nerve damage, blindness, shooting pains, urinary incontinence, and degeneration of the joints.[6]

In most cases, lesions present bilaterally. However, in rare cases, lesions have been seen unilaterally.[2] Moreover, general symptoms of posterior spinal artery infarcts include ipsilateral loss of proprioceptive sensation, fine touch, pressure, and vibration below the lesion; deep tendon areflexia; and in severe circumstances, complete paralysis below the portion of the spinal cord affected.[1]

Diagnosis

Complete spinal imaging, X-rays, computed tomography (CT), or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can be used to identify infarctions on the dorsal columns.[6] Imaging alone is often inconclusive and does not present a full analysis of the affected columns. Clinical history, blood and cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) tests can also be used to make a full diagnosis.[1]

Treatment

Treatment for posterior spinal artery syndrome depends on the causes and symptoms, as well as the source of the infarction. The main goal of treatment is to stabilize the spine. Possible treatments include airway adjuncts; the use of ventilators; full spinal precautions and immobilization; and injections of dopamine.[6][7] While there is no definitive cure for posterior cord syndrome, treatment and supportive care can be provided based on the patient's symptoms. Therapy and rehabilitative care including walking aids, physical, occupational, and psychotherapy can help ease the symptoms associated with PSAS. Acute therapy can include intensive medical care and analgesia. Corticosteroids are used to reduce any inflammation or swelling. Bracing or surgical repair can be done to stabilize the spinal fracture.[8]

Research

It has been difficult to make any breakthroughs in diagnosis and/or treatment of PSAS as symptoms are not specific in nature and can vary based on the exact location of spinal cord lesions. In addition, the demographics of patients with PSAS are widespread as the onset of symptoms typically follows a traumatic event. Additionally, research has suffered setbacks because PSAS is rare with few documented cases, unlike anterior spinal artery syndrome.[1][3][9]

However, ongoing research has helped in differentiating PSAS from other brain injuries. Therefore, better therapies for PSAS treatment can be developed. For instance, one study suggests that a tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) therapy intervention, commonly used in stroke patients,[10] may aid in treating patients with symptoms of PSAS.[11]

References

- 1 2 3 4 "Incomplete Spinal Cord Injury". Spinal Cord.com. Spinal Cord.com. Retrieved 27 March 2018.

- 1 2 Richard, Sebastien; Abdallah, Chifaou; Chanson, Anne; Foscolo, Sylvain; Baillot, Pierre-Alexandre; Ducroucp, Xavier (2014). "Unilateral posterior cervical spinal cord infarction due to spontaneous vertebral artery dissection". The Journal of Spinal Cord Medicine. J Spinal Cord Med. 37 (2): 233–236. doi:10.1179/2045772313Y.0000000125. PMC 4066433. PMID 24090478.

- 1 2 Mascalchi, Mario; Cosottini, Mirco; Giampiero, Ferrito; Salvi, Fabrizio; Nencini, Patrizia; Quilici, Nello (1998). "Posterior Spinal Artery Infarct" (PDF). AJNR. American Journal of Neuroradiology. 19 (2): 361–3. PMC 8338164. PMID 9504495. Retrieved 27 March 2018.

- ↑ "Posterior cord syndrome - OrthopaedicsOne Articles - OrthopaedicsOne". www.orthopaedicsone.com. Retrieved 2018-04-25.

- ↑ Pandey, Shuchit; V Holla, Vikram; Rizvi, Imran; Qavi, Abdul; Shukla, Rakesh (2016-07-07). "Can vitamin B12 deficiency manifest with acute posterolateral or posterior cord syndrome?". Spinal Cord Series and Cases. 2 (1): 16006–. doi:10.1038/scsandc.2016.6. ISSN 2058-6124. PMC 5129416. PMID 28053750.

- 1 2 3 "Medical Definition of Tabes dorsalis". MedicineNet.com. MedicineNet.com. Retrieved 27 March 2018.

- ↑ McKinley, William; Santos, Katia; Meada, Michelle; Brooke, Karen (2007). "Incidence and Outcomes of Spinal Cord Injury Clinical Syndromes". The Journal of Spinal Cord Medicine. J Spinal Cord Med. 30 (3): 215–224. doi:10.1080/10790268.2007.11753929. PMC 2031952. PMID 17684887.

- ↑ "Complete spinal cord injury – Knowledge for medical students and physicians". www.amboss.com. Retrieved 2018-04-25.

- ↑ Murata, Kiyoko; Ikeda, Ken; Muto, Mitsuaki; Hirayama, Takeshisa; Kano, Osamu; Iwasaki, Yasuo (2012). "A case of Posterior Spinal Artery Syndrome in the Cervical Cord: A Review of the Clinicoradiological Literature". Internal Medicine (Tokyo, Japan). Internal Medicine. 51 (7): 803–7. doi:10.2169/internalmedicine.51.6922. PMID 22466844. Retrieved 27 March 2018.

- ↑ "Tissue Plasminogen Activator" (PDF). Stroke Association. The Stroke Collaborative. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 March 2018. Retrieved 27 March 2018.

- ↑ Sakurai, Takeo; Wakida, Kenji; Nishida, Hiroshi (2016). "Cervical Posterior Spinal Artery Syndrome: A Case Report and Literature Review". Journal of Stroke and Cerebrovascular Diseases. 25 (6): 1552–6. doi:10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2016.02.018. PMID 27012218. Retrieved 27 March 2018.