| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

poly(2-propenamide) | |

| Other names

poly(2-propenamide), poly(1-carbamoylethylene) | |

| Identifiers | |

| ChemSpider |

|

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.118.050 |

| UNII |

|

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

| Properties | |

| (C3H5NO)n | |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

Infobox references | |

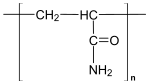

Polyacrylamide (abbreviated as PAM or pAAM) is a polymer with the formula (-CH2CHCONH2-). It has a linear-chain structure. PAM is highly water-absorbent, forming a soft gel when hydrated. In 2008, an estimated 750,000,000 kg were produced, mainly for water treatment and the paper and mineral industries.[1]

Physicochemical properties

Polyacrylamide is a polyolefin. It can be viewed as polyethylene with amide substituents on alternating carbons. Unlike various nylons, polyacrylamide is not a polyamide because the amide groups are not in the polymer backbone. Owing to the presence of the amide (CONH2) groups, alternating carbon atoms in the backbone are stereogenic (colloquially: chiral). For this reason, polyacrylamide exists in atactic, syndiotactic, and isotactic forms, although this aspect is rarely discussed. The polymerization is initiated with radicals and is assumed to be stereorandom.[1]

Copolymers and modified polymers

Linear polyacrylamide is a water-soluble polymer. Other polar solvents include DMSO and various alcohols. Cross-linking can be introduced using N,N-methylenebisacrylamide. Some crosslinked materials are swellable but not soluble, i.e., they are hydrogels.

Partial hydrolysis occurs at elevated temperatures in aqueous media, converting some amide substituents to carboxylates. This hydrolysis thus makes the polymer particularly hydrophilic. The polymer produced from N,N-dimethylacrylamide resists hydrolysis.

Copolymers of acrylamide include those derived from acrylic acid.

Uses

In the 1970s and 1980s, the proportionately largest use of these polymers was in water treatment.[2] The next major application by weight is additives for pulp processing and papermaking. About 30% of polyacrylamide is used in the oil and mineral industries.[1]

Flocculation

One of the largest uses for polyacrylamide is to flocculate solids in a liquid. This process applies to water treatment, and processes like paper making and screen printing. Polyacrylamide can be supplied in a powder or liquid form, with the liquid form being subcategorized as solution and emulsion polymer.

Even though these products are often called 'polyacrylamide', many are actually copolymers of acrylamide and one or more other species, such as an acrylic acid or a salt thereof. These copolymers have modified wetting and swellability.

The ionic forms of polyacrylamide has found an important role in the potable water treatment industry. Trivalent metal salts, like ferric chloride and aluminum chloride, are bridged by the long polymer chains of polyacrylamide. This results in significant enhancement of the flocculation rate. This allows water treatment plants to greatly improve the removal of total organic content (TOC) from raw water.

Fossil fuel industry

In oil and gas industry polyacrylamide derivatives especially co-polymers have a substantial effect on production by enhanced oil recovery by viscosity enhancement. High viscosity aqueous solutions can be generated with low concentrations of polyacrylamide polymers, which are injected to improve the economics of conventional water-flooding. In a separate application, hydraulic fracturing benefits from drag reduction resulting from injection of these solutions. These applications use large volumes of polymer solutions at concentration of 30–3000 mg/L.[3]

Soil conditioning

The primary functions of polyacrylamide soil conditioners are to increase soil tilth, aeration, and porosity and reduce compaction, dustiness and water run-off. Typical applications are 10 mg/L, which is still expensive for many applications.[3] Secondary functions are to increase plant vigor, color, appearance, rooting depth, and emergence of seeds while decreasing water requirements, diseases, erosion and maintenance expenses. FC 2712 is used for this purpose.

Molecular biology laboratories

Polyacrylamide is also often used in molecular biology applications as a medium for electrophoresis of proteins and nucleic acids in a technique known as PAGE. PAGE was first used in a laboratory setting in the early 1950s. In 1959, the groups of Davis and Ornstein[4] and of Raymond and Weintraub[5] independently published on the use of polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis to separate charged molecules.[5] The technique is widely accepted today, and remains a common protocol in molecular biology labs.

Acrylamide has other uses in molecular biology laboratories, including the use of linear polyacrylamide (LPA) as a carrier, which aids in the precipitation of small amounts of nucleic acids (DNA and RNA).[6][7] Many laboratory supply companies sell LPA for this use.[8] In addition, under certain conditions, it can be used to selectively precipitate only RNA species from a mixture of nucleic acids.[7]

Mechanobiology

The elastic modulus of polyacrylamide can be changed by varying the ratio of monomer to cross-linker during the fabrication of polyacrylamide gel.[9] This property makes polyacrylamide useful in the field of mechanobiology, as a number of cells respond to mechanical stimuli.[10]

Niche uses

The polymer is also used to make Gro-Beast toys, which expand when placed in water, such as the Test Tube Aliens. Similarly, the absorbent properties of one of its copolymers can be utilized as an additive in body-powder.

It has been used in Botox as a subdermal filler for aesthetic facial surgery (see Aquamid).

It was also used in the synthesis of the first Boger fluid.

Environmental effects

Considering the volume of polyacrylamide produced, these materials have been heavily scrutinized with regards to environmental and health impacts.[11][12]

Polyacrylamide is of low toxicity but its precursor acrylamide is a neurotoxin and carcinogen.[1] Thus, concerns naturally center on the possibility that polyacrylamide is contaminated with acrylamide.[12][13] Considerable effort is made to scavenge traces of acrylamide from the polymer intended for use near food.[1]

Additionally, there are concerns that polyacrylamide may de-polymerise to form acrylamide. Under conditions typical for cooking, polyacrylamide does not de-polymerise significantly.[14] The single claim that polyacrylamide reverts to acrylamide[15] has been widely challenged.[16][17][18]

Polyacrylamide is most commonly partially biodegraded by the action of amidases, producing ammonia and polyacrylates. Polyacrylates are hard to biodegrade, but some soil microbe cultures have been shown to do so in aerobic condtions.[19]

See also

- Aquamid

- Chitosan

- Rhoca-Gil

- Sodium polyacrylate, a similar material

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Herth G, Schornick G, Buchholz F (2015). "Polyacrylamides and Poly(Acrylic Acids)". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. pp. 1–16. doi:10.1002/14356007.a21_143.pub2. ISBN 978-3527306732.

- ↑ "Polyacrylamide". Hazardous Substances Data Bank. United States National Library of Medicine. February 14, 2003. Consumption Patterns. CASRN: 9003-05-8. Archived from the original on 30 December 2017. Retrieved November 30, 2013.

- 1 2 Xiong B, Loss RD, Shields D, Pawlik T, Hochreiter R, Zydney AL, Kumar M (2018). "Polyacrylamide Degradation and Its Implications in Environmental Systems". Clean Water. 1. doi:10.1038/s41545-018-0016-8. S2CID 135203788.

- ↑ "Disc Electrophoresis". Pipeline.com. Archived from the original on 26 September 2011. Retrieved 11 June 2012. citing: Ornstein L (December 1964). "Disc Electrophoresis. I. Background and Theory". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 121 (2): 321–49. Bibcode:1964NYASA.121..321O. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1964.tb14207.x. PMID 14240533. S2CID 28591995.

- 1 2 Raymond S, Weintraub L (September 1959). "Acrylamide gel as a supporting medium for zone electrophoresis". Science. 130 (3377): 711. Bibcode:1959Sci...130..711R. doi:10.1126/science.130.3377.711. PMID 14436634. S2CID 7242716. citing: Davis DR, Budd RE (June 1959). "Continuous electrophoresis; quantitative fractionation of serum proteins". The Journal of Laboratory and Clinical Medicine. 53 (6): 958–65. PMID 13665142.

- ↑ Gaillard C, Strauss F (January 1990). "Ethanol precipitation of DNA with linear polyacrylamide as carrier". Nucleic Acids Research. 18 (2): 378. doi:10.1093/nar/18.2.378. PMC 330293. PMID 2326177.

- 1 2 Muterko A (2022-01-02). "Selective precipitation of RNA with linear polyacrylamide". Nucleosides, Nucleotides & Nucleic Acids. 41 (1): 61–76. doi:10.1080/15257770.2021.2007397. PMID 34809521. S2CID 244490750.

- ↑ Sigma-Aldrich. "GenElute-LPA". biocompare.com. Archived from the original on 2011-07-18.

- ↑ Denisin AK, Pruitt BL (August 2016). "Tuning the Range of Polyacrylamide Gel Stiffness for Mechanobiology Applications". ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces. 8 (34): 21893–21902. doi:10.1021/acsami.5b09344. PMID 26816386.

- ↑ Pelham RJ, Wang Y (December 1997). "Cell locomotion and focal adhesions are regulated by substrate flexibility". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 94 (25): 13661–13665. Bibcode:1997PNAS...9413661P. doi:10.1073/pnas.94.25.13661. PMC 28362. PMID 9391082.

- ↑ Environment Canada; Health Canada (August 2009). "Screening Assessment for the Challenge: 2-Propenamide (Acrylamide)". Environment and Climate Change Canada. Government of Canada.

- 1 2 Dotson GS (April 2011). "NIOSH skin notation (SK) profile: acrylamide [CAS No. 79-06-1]" (PDF). DHHS (NIOSH) Publication No. 2011-139. National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- ↑ Woodrow JE, Seiber JN, Miller GC (April 2008). "Acrylamide release resulting from sunlight irradiation of aqueous polyacrylamide/iron mixtures". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 56 (8): 2773–2779. doi:10.1021/jf703677v. PMID 18351736.

- ↑ Ahn JS, Castle L (November 2003). "Tests for the depolymerization of polyacrylamides as a potential source of acrylamide in heated foods". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 51 (23): 6715–6718. doi:10.1021/jf0302308. PMID 14582965.

- ↑ Smith EA, Prues SL, Oehme FW (June 1997). "Environmental degradation of polyacrylamides. II. Effects of environmental (outdoor) exposure". Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety. 37 (1): 76–91. doi:10.1006/eesa.1997.1527. PMID 9212339. Archived from the original on 2016-04-20. Retrieved 2007-11-02.

- ↑ Kay-Shoemake JL, Watwood ME, Lentz RD, Sojka RE (August 1998). "Polyacrylamide as an organic nitrogen source for soil microorganisms with potential effects on inorganic soil nitrogen in agricultural soil". Soil Biology and Biochemistry. 30 (8/9): 1045–1052. doi:10.1016/S0038-0717(97)00250-2.

- ↑ Gao J, Lin T, Wang W, Yu J, Yuan S, Wang S (1999). "Accelerated chemical degradation of polyacrylamide". Macromolecular Symposia. 144: 179–185. doi:10.1002/masy.19991440116. ISSN 1022-1360.

- ↑ Ver Vers LM (December 1999). "Determination of acrylamide monomer in polyacrylamide degradation studies by high-performance liquid chromatography". Journal of Chromatographic Science. 37 (12): 486–494. doi:10.1093/chromsci/37.12.486. PMID 10615596.

- ↑ Nyyssölä A, Ahlgren J (April 2019). "Microbial degradation of polyacrylamide and the deamination product polyacrylate". International Biodeterioration & Biodegradation. 139: 24–33. doi:10.1016/j.ibiod.2019.02.005. S2CID 92617790.