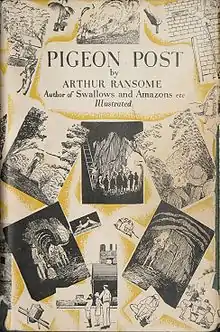

Front cover of first edition | |

| Author | Arthur Ransome |

|---|---|

| Illustrator | Arthur Ransome |

| Cover artist | Ransome |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Series | Swallows and Amazons |

| Genre | Children's adventure novel |

| Publisher | Jonathan Cape |

Publication date | 1936 |

| Media type | Print (hardcover & paperback) |

| Pages | 383 pp (first edition) |

| ISBN | 9780224021241 |

| OCLC | 634672 |

| LC Class | PZ7.R175 Pi[1] |

| Preceded by | Coot Club |

| Followed by | We Didn't Mean To Go To Sea |

Pigeon Post is an English children's adventure novel by Arthur Ransome, published by Jonathan Cape in 1936. It was the sixth of twelve books Ransome completed in the Swallows and Amazons series (1930 to 1947). He won the inaugural Carnegie Medal from the Library Association, recognising it as the year's best children's book by a British subject.[2]

This book is the only one of the Swallows and Amazons books which does not feature sailing-related plots: boats appear only in passing, as a mode of transport. All the action takes place on and under the fells surrounding the Lake, as the characters attempt to discover gold in the Lake District hills.[3][4]

Plot summary

The Swallows, Amazons and Ds are camping in the Blackett family's garden at Beckfoot. The Swallow is not available for sailing. James Turner (Captain Flint) has sent word that he is returning from an expedition to South America prospecting for gold, and has sent "Timothy" ahead. As he can be let loose in the study, the Amazons and D's have already deduced that Timothy is an armadillo, and Titty, Dick and Peggy make a box for him, but he does not arrive. Slater Bob, an old slate miner, tells them a story about a lost gold vein in the fells. As Captain Flint has been unsuccessful in his prospecting trip, the children plan to prospect for gold on High Topps instead, as a surprise for Flint.

When Mrs. Blackett shows doubts, the children prove they can stay in touch with Beckfoot using the homing pigeons that give the book its name, and earn permission to move camp to Tyson's Farm, up near the fells, to be closer to the prospecting grounds. They are disappointed in that Mrs Tyson does not permit them to cook over a campfire, owing to drought conditions and her fear of fires, meaning that they have to keep in time with her meal-schedules. Titty eventually finds a spring by dowsing, and they move closer to the Topps. They send daily messages home by pigeon.

While exploring the ground, they notice a rival prospector whom they call "Squashy Hat". After days of prospecting, Roger finds a seam of gold-coloured mineral in an old mining excavation, and crush enough of it in order to produce a golden ingot in a charcoal furnace. Unfortunately, it disappears when the crucible breaks, and Dick, the expedition's professor, has only a small amount to test. Meanwhile, Squashy Hat is consulting the old slate miner, entering through beneath the fell via an old mine working. Seeing him, the younger three children walk inside the fell, resulting in Titty having to follow them in to look for them, with very nearly fatal results. Christina Hardyment writes that venturing into the Old Level was probably the most idiotic thing that any of Ransome's characters ever did.

Captain Flint returns home, and finds Dick doing chemical tests on the putative gold in his study. Dick has read that gold dissolves in aqua regia, but Captain Flint explains "Aqua regia will dissolve almost anything. The point about gold is it won't dissolve in anything else…". He shows Dick by other tests that they have found copper pyrites, a rich copper ore.[5]

A pigeon named Sappho, whom they had previously labeled as "undependable", suddenly arrives with an urgent message from Titty, FIRE HELP QUICK. Captain Flint rings Colonel Jolys, who musters his volunteer fire fighters, and they all rush to help save the Topps. After the fire on the fells is extinguished, Squashy Hat is revealed to be Captain Flint's friend Timothy, who has been too shy to introduce himself to the children. Captain Flint is pleased to find copper, as he had talked with Timothy above Pernambuco in South America about new ways of prospecting for copper on the fells, and planned to look for copper using new methods not known to the "old miners". Indeed, when the search for gold in South America was unsuccessful, their second plan was to look for the copper in the Topps.

Whilst the mining project is briefly mentioned in Secret Water, the project itself recurs in the later book The Picts and the Martyrs, with Slater Bob turning back to mining for metal instead of slate.

Critical reception

The British Library Association presented Ransome with the inaugural Carnegie Medal at its annual conference in June 1936. Notices in The New York Times recognised that as comparable to the American Newbery Medal. The following month Lippincott of Philadelphia published the first U.S. edition, which Ellen Lewis Buell reviewed for the newspaper in August. She noted the children's "vivid collective imagination which turned play into serious business" and observed, "It is the portrayal of this spirit which makes play a matter of desperate yet enjoyable earnestness which gives their distinctive stamp to Mr. Ransome's books. ... Because he understands the whole-heartedness of youth he can invest a momentary experiment, such as young Roger's Indian scout work, with real suspense."[6]

Dedication

Ransome made use of the mining and prospecting knowledge of his friend Oscar Gnosspelius, who appears in the book as "Squashy Hat" and to whom the work is dedicated.[7]

See also

References

- ↑ "Pigeon post" (first edition). Library of Congress Catalog Record. Retrieved 3 November 2012.

- ↑ (Carnegie Winner 1936). Living Archive: Celebrating the Carnegie and Greenaway Winners. CILIP. Retrieved 2012-07-23.

- ↑ Wardale, Roger (1991). Nancy Blackett. London: Jonathan Cape. p. 91.

- ↑ Hardyment, Christina (1984). Arthur Ransome & Captain Flint's Trunk. London: Jonathan Cape.

- ↑ Quinan, Adam. "The Chemistry of Pigeon Post". All Things Ransome. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- ↑ "The New Books for Boys and Girls", Ellen Buell Lewis, The New York Times, 22 August 1937, p. BR10.

- ↑ Hardyment (1984) p. 80

External links

- Pigeon Post at Faded Page (Canada)

- Pigeon Post in libraries (WorldCat catalog) —immediately, first US edition