| Penhallam | |

|---|---|

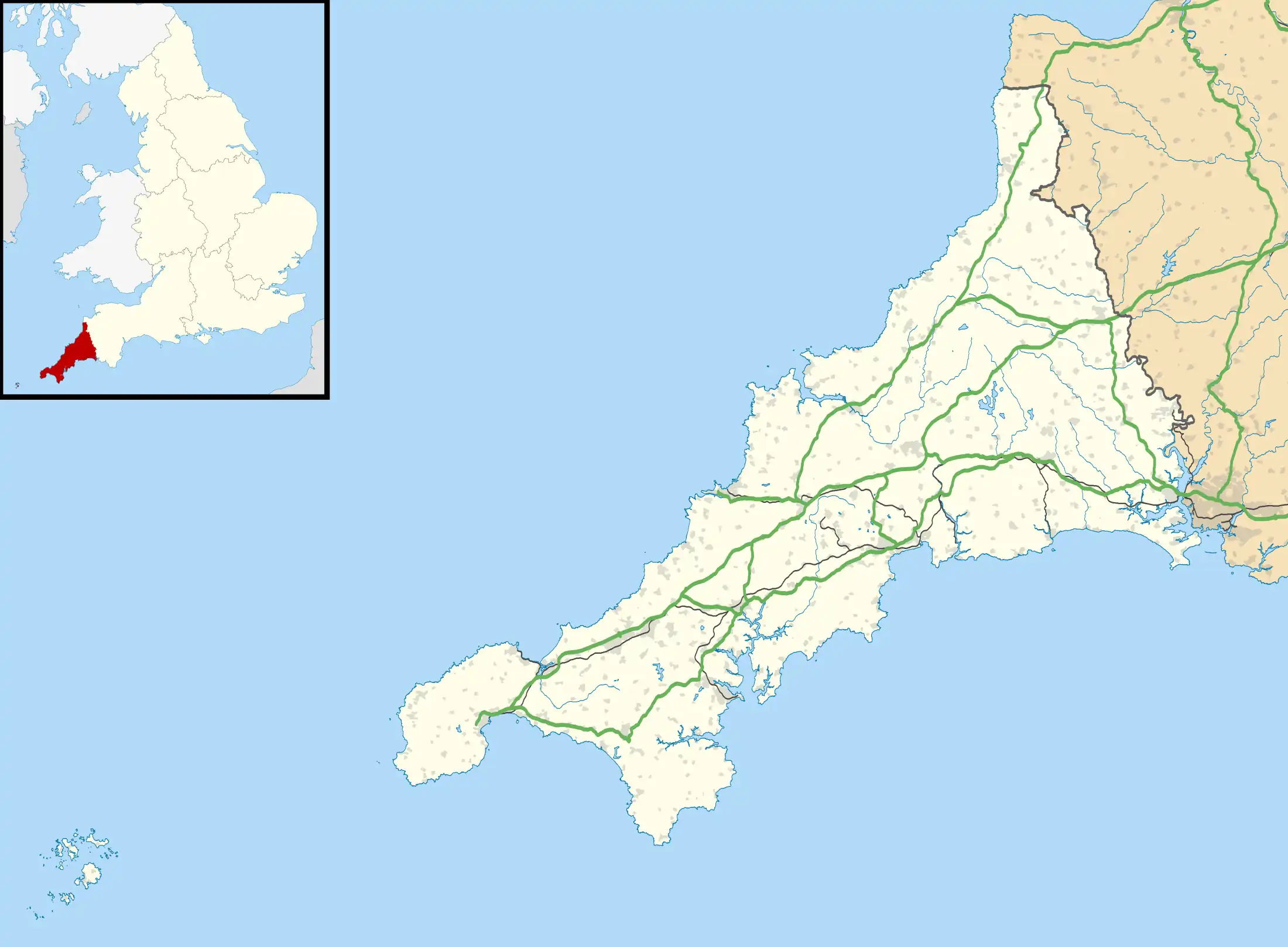

| Jacobstow, Cornwall | |

The exposed foundations | |

Penhallam | |

| Coordinates | 50°44′56″N 4°31′06″W / 50.74901°N 4.51831°W |

| Type | Fortified manor house |

| Site information | |

| Controlled by | English Heritage |

| Open to the public | Yes |

| Condition | Only foundations remain |

Penhallam is the site of a fortified manor house near Jacobstow in Cornwall, England. There was probably an earlier, 11th-century ringwork castle on the site, constructed by Tryold or his son, Richard fitz Turold in the years after the Norman invasion of 1066. Their descendants, in particular Andrew de Cardinham, created a substantial, sophisticated manor house at Penhallam between the 1180s and 1234, building a quadrangle of ranges facing onto an internal courtyard, surrounded by a moat and external buildings. The Cardinhams may have used the manor house for hunting expeditions in their nearby deer park. By the 14th century, the Cardinham male line had died out and the house was occupied by tenants. The surrounding manor was broken up and the house itself fell into decay and robbed for its stone. Archaeological investigations between 1968 and 1973 uncovered its foundations, unaltered since the medieval period, and the site is now managed by English Heritage and open to visitors.

11th century

Penhallam Manor is located near Jacobstow, in a sheltered valley leading down to the sea, at the junction of two tributaries of the River Neet.[1] The valley is now a mixture of woodland and marshes, although in the medieval period it would have formed a more open area of land.[2]

There may have been an earlier Anglo-Saxon building on the site, although no traces have been found.[3] Shortly after the Norman conquest of England, however, a ringwork castle was probably built at Penhallam by the invaders, and a substantial manor was recorded as being present there in the Domesday survey of 1086.[4][lower-alpha 1] The construction work was carried out either by a one Tryold - a follower of Robert, the Count of Mortain - or his son, Richard fitz Turold.[6] In the wake of the invasion, Robert acquired vast lands in Cornwall, and in turn the pair were granted the honour of Cardinham, a feudal landing holding comprising 28 manors.[7]

The castle at Penhallam took advantage of a raised area of ground above the marshes, with a circular bank of earth possibly up to 50 feet (15 m) wide and 12 feet (3.7 m) high, surrounded by a shallow, wet moat up to 38 feet (12 m) across. A hall would have been constructed within the ringwork, up to 60 feet (18 m) in length, possibly using stone or cobwalling.[8] A bailey probably lay just to the south, containing the stables and outbuildings, probably within the earth bank that surrounds the modern farmstead.[9]

12th-13th centuries

Tyrold and Richard fitz Turold founded what eventually became known as the Cardinham family, who became powerful Cornish landowners and agents for the Crown.[10] Penhallam was an important manor for them, and it may have acted as their administrative caput before the family established their main castle at Cardinham.[11] The family probably visited several times a year, possibly to go hunting in the deer park they established stretching up the valleys to the south-west.[12] From around 1180 onwards, under either Robert fitz William or Robert de Cardinham, the manor house began to be redeveloped, with the ringwork defences being mostly demolished in the process.[13]

The first work involved building a camera - a chamber alongside the existing hall - and was carried out between 1180 and 1200.[14] A set of rooms known as a wardrobe, used for accommodation and storage, and a garderobe followed on the north end.[9] Robert's son, Andrew de Cardinham, inherited the family's estates around 1226 and carried on expanding Penhallam, building a new hall, a service wing - including a kitchen, buttery, pantry, and a combined brewhouse and bakehouse - a chapel, lodgings, and a gatehouse.[15] The gatehouse was protected by a drawbridge, leading to a set of stables and other service buildings on the site of the former bailey.[16] The exterior walls were whitewashed and would have made the property highly visible from the nearest road.[2] By around 1234, the result was a substantial, sophisticated manor house, with a large quadrangle of ranges, approximately 158 by 125 feet (48 by 38 m) across, facing onto an internal courtyard.[17]

Andrew gave the manor to Emma, his widowed sister-in-law, for the remainder of her life in 1234; Andrew left no male heir, and on his death the manor passed to his daughter, Isolda de Cardinham.[18] Isolda then gave the manor to Sir Henry de Champernowne, a member of a powerful Devonshire family, at some point before 1270.[19] Around this time, the drawbridge was replaced with a stone bridge and, around the end of the century, the southern kitchen and lodging buildings were rebuilt.[2]

14th-21st centuries

By the 14th century, Penhallam was occupied by the Beaupré family, tenants of the Champernownes, and by 1330 the manor had begun to be subdivided into smaller units of land.[20] The manor house was abandoned and fell into disrepair; the roof collapsed at some point after 1360.[21] The walls were robbed for their stone and by 1428 the manor itself had ceased to exist.[22] A small farmstead, called Berry or Bury Court, was established on the site of the former stables.[23]

In the mid-20th century, plans were drawn up to clear the area around the former house, then owned by Roger Money-Kyrle and managed by Economic Forestry (South West) Ltd., in order to plant a new forest.[24] Initial archaeological investigations were carried out by the Ministry of Public Building and Works in 1968, and work continued until 1973. The foundations of the walls, exposed by the archaeologists, were consolidated and protected, and the moat cleaned out and refilled.[2] The site was protected under UK law as a scheduled monument in 1996, and is now managed by English Heritage and open to visitors.[25]

See also

Notes

- ↑ The existence of an 11th-century ringwork at Penhallam was first proposed by the archaeologist Guy Beresford, following his investigations at the site between 1968 and 1973. Beresford noted that the investigations had uncovered an earth bank running around the site, resembling that found at ringwork castles, which had then been destroyed prior to the 12th and 13th century construction work. No hard dating evidence for early Norman buildings could be found, but Beresford argued that this was not inconsistent with the building methods used during the period. Beresford highlighted the other ringworks known to have been constructed by the early Cardinham family during the period in the region, and the importance of the Penhallam manor during the early Norman period. Several other historians, including Anthony Emery and Ian Soulsby, have followed this analysis. Ann Preston-Jones and Peter Rose, are more cautious however, stressing the inconclusive nature of the archaeological record and describing the site as a "possible ringwork", suggesting that the ringwork castle at Week St Mary may have been used to oversee the Penhallam manor. Philip Davis describes the existence of the ringwork castle as "probable" rather than "certain".[5]

References

- ↑ Beresford 1974, pp. 91–92; "Penhallam Manor", Historic Environment service of Cornwall Council, retrieved 23 December 2017

- 1 2 3 4 Emery 2006, p. 614

- ↑ Beresford 1974, pp. 98–99

- ↑ Beresford 1974, pp. 97–98; Soulsby 1976, p. 148

- ↑ Beresford 1974, p. 126; Soulsby 1976, p. 148; Emery 2006, pp. 614–615; Preston-Jones & Rose 1986, pp. 170–171; Davis, Philip, "Penhallam Manor, Jacobstow", retrieved 24 December 2017

- ↑ Beresford 1974, p. 95

- ↑ Beresford 1974, p. 94; Golding, Brian (2004), "Robert, count of Mortain, (d. 1095)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.), Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/19339 (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ Beresford 1974, pp. 97–100

- 1 2 Beresford 1974, p. 100

- ↑ Beresford 1974, pp. 94–96; "History of Penhallam Manor", English Heritage, retrieved 23 December 2017

- ↑ Emery 2006, p. 614; Soulsby 1976, p. 148

- ↑ Emery 2006, p. 614; Soulsby 1976, p. 148; Herring 2003, pp. 38–39

- ↑ Beresford 1974, pp. 95–96, 100

- ↑ Beresford 1974, pp. 100–102

- ↑ Beresford 1974, pp. 96, 101–102; Historic England, "Penhallam medieval moated manor house, 360m south west of Ashbury Camp (1013669)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 23 December 2017

- ↑ Beresford 1974, p. 100; Emery 2006, p. 614; "Penhallam Manor", Historic Environment service of Cornwall Council, retrieved 23 December 2017

- ↑ Beresford 1974, pp. 98, 100; Emery 2006, p. 614; "Penhallam Manor", Historic Environment service of Cornwall Council, retrieved 23 December 2017

- ↑ Beresford 1974, pp. 96, 101

- ↑ Beresford 1974, pp. 96–97

- ↑ Beresford 1974, pp. 96–97; "History of Penhallam Manor", English Heritage, retrieved 23 December 2017

- ↑ Beresford 1974, p. 97; Emery 2006, p. 614

- ↑ Beresford 1974, pp. 92, 97

- ↑ Beresford 1974, p. 90; "Cornwall & Scilly HER", Heritage Gateway, retrieved 23 December 2017

- ↑ Beresford 1974, p. 127

- ↑ Historic England, "Penhallam medieval moated manor house, 360m south west of Ashbury Camp (1013669)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 23 December 2017; "Penhallam Manor", Historic Environment service of Cornwall Council, retrieved 23 December 2017

Bibliography

- Beresford, Guy (1974). "The Medieval Manor of Penhallam, Jacobstow, Cornwall". Medieval Archaeology. 18: 90–145. doi:10.1080/00766097.1974.11735366.

- Emery, Anthony (2006). Greater Medieval Houses of England and Wales, 1300–1500, Volume 3: Southern England. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-58132-5.

- Herring, Peter (2003). "Cornish Medieval Deer Parks". In Wilson-North, Robert (ed.). The Lie of the Land: Aspects of the Archaeology and History of the Designed Landscape in the South West of England. Exeter, UK: The Mint Press. pp. 34–50. ISBN 1-903356-22-9.

- Preston-Jones, Ann; Rose, Peter (1986). "Medieval Cornwall". Cornish Archaeology. 25: 135–185.

- Soulsby, Ian N. (1976). "Richard Fitz Turold, Lord of Penhallam, Cornwall". Medieval Archaeology. 20: 146–148.