This article covers the phonology of the Orsmaal-Gussenhoven dialect, a variety of Getelands (a transitional dialect between South Brabantian and West Limburgish) spoken in Orsmaal-Gussenhoven, a village in the Linter municipality.[1]

Consonants

| Labial | Alveolar | Postalveolar | Dorsal | Glottal | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| hard | soft | hard | soft | |||||

| Nasal | m ⟨m⟩ | n ⟨n⟩ | ŋ ⟨ng⟩ | |||||

| Stop | fortis | p ⟨p⟩ | t ⟨t⟩ | tʲ ⟨tj⟩ | k ⟨k⟩ | kʲ ⟨kj⟩ | ||

| lenis | b ⟨b⟩ | d ⟨d⟩ | ||||||

| Fricative | fortis | f ⟨f⟩ | s ⟨s⟩ | ʃ ⟨sj⟩ | x ⟨ch⟩ | |||

| lenis | v ⟨v⟩ | z ⟨z⟩ | (ʒ) ⟨zj⟩ | ɣ ⟨g⟩ | ɦ ⟨h⟩ | |||

| Approximant | w ⟨w⟩ | l ⟨l⟩ | j ⟨j⟩ | |||||

| Trill | r ⟨r⟩ | |||||||

Obstruents

- The fortis–lenis distinction in the case of plosives manifests itself purely through voicing - /p, t, tʲ, k, kʲ/ are voiceless, whereas /b/ and /d/ are voiced. In the case of the fricatives, the same is true of the /ʃ–ʒ/ pair, though /ʒ/ is a non-native phoneme that occurs only in the word-initial position. It can be affricated to [dʒ], but the /ʃ–ʒ/ contrast is not stable and the two phonemes undergo a variable merger to [ʃ]. In the case of the native fortis–lenis pairs of fricatives, the contrast between /f, s, x/ on the one hand and /v, z, ɣ/ on the other manifests itself mainly through the less energetic articulation of the latter, particularly in the case of the velar /ɣ/, which is mostly voiceless. In the case of /v, z/, they can be partially voiced in the word-initial position, with the second part being voiceless. In the intervocalic position, they are completely voiceless.[3]

- /p, b/ are bilabial, whereas /f, v/ are labiodental.[1]

- /k, kʲ/ are velar.[1]

- The exact place of articulation of /x, ɣ/ varies:

- Word-initial /x/ is restricted to the sequence /sx/.[3]

- /ɦ/ may be dropped by some speakers.[3]

- /p, t, tʲ, k, kʲ, v, z/ may be affricated to [pɸ, ts, tɕ, kx, kxʲ, b̥v̥, d̥z̥]. Peters (2010) does not specify the environment(s) in which the affrication of /v/ and /z/ takes place, but it may occur word-initially, as in the case of the non-native /ʒ/. In the case of stops, it occurs in pre-pausal position, where voiced fricatives are banned.[3]

Sonorants

- /m/ is bilabial and so is /w/, which is a bilabial approximant without velarization: [β̞].[1] In this article, the latter is written with ⟨w⟩, following the recommendations of Carlos Gussenhoven regarding transcribing the corresponding Standard Dutch phone.[4]

- /n, l, r/ are alveolar.[1]

- /n/ before /k/ is pronounced as follows:

- Word-final [ɲ] appears only in loanwords from French.[3]

- /l/ tends to be velarized, especially postvocalically.[3]

- /r/ has a few possible realizations:

- Apical trill [r] or an apical fricative [ɹ̝] before a stressed vowel in word-initial syllables.[3]

- Intervocalically and in the onset after a consonant, it may be a tap [ɾ].[3]

- Word-final /r/ is highly variable; the most frequent variants are an apical fricative trill [r̝], an apical fricative [ɹ̝] and an apical non-sibilant affricate [dɹ̝]. The last two variants tend to be voiceless ([ɹ̝̊, tɹ̝̊]) in pre-pausal position.[3]

- The sequence /ər/ can be vocalized to [ɐ] or [ə].[5]

- /ŋ/ is velar, whereas /j/ is palatal.[1]

- /w, j/ appear only word-initially and intervocalically.[3]

Final devoicing and assimilation

Just like Standard Dutch, Orsmaal-Gussenhoven dialect devoices all obstruents at the ends of words.[3]

Morpheme-final /p, t, k/ may be voiced if a voiced plosive or a vowel follows.[3]

Vowels

The vowel system of the Orsmaal-Gussenhoven dialect is considerably richer than that of Standard Dutch. It features a phonemic distinction between close and open variants of the vowels corresponding to SD /ʏ/ and /ɔ/ (with the close variants being /ʏ/ and /ʊ/ and the open ones /œ/ and /ɒ/), long open-mid vowels (which are only marginal in SD) as well as a number of diphthongs that do not exist in the standard language.

| Front | Central | Back | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| unrounded | rounded | ||||||||

| short | long | short | long | short | long | short | long | ||

| Close | iː ⟨ie⟩ | yː ⟨uu⟩ | u ⟨oe⟩ | uː ⟨oê⟩ | |||||

| Close-mid | ɪ ⟨i⟩ | eː ⟨ee⟩ | ʏ ⟨u⟩ | øː ⟨eu⟩ | ə ⟨e⟩ | ʊ ⟨ó⟩ | oː ⟨oo⟩ | ||

| Open-mid | ɛ ⟨e⟩ | ɛː ⟨ae⟩ | œ ⟨ö⟩ | œː ⟨äö⟩ | ɒ ⟨o⟩ | ɒː ⟨ao⟩ | |||

| Open | a ⟨a⟩ | aː ⟨aa⟩ | |||||||

| Marginal | y ⟨uu⟩ o ⟨oo⟩ | ||||||||

| Diphthongs | closing | uɪ ⟨oei⟩ aɪ ⟨ai⟩ aʊ ⟨aw⟩ | |||||||

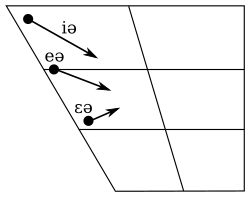

| centering | iə ⟨ieë⟩ eə ⟨eë⟩ ɛə ⟨aeë⟩ ɔə ⟨oa⟩ | ||||||||

- Peters gives six more diphthongs, which are [eɪ, øʏ, əʊ, ɛɪ, œʏ, ɔʊ]. He gives no evidence for their phonemic status as phonemes separate from /eː, øː, oː, ɛː, œː, ɒː/ and no information on their distribution, apart from the fact that both [əʊ, ɛɪ] and [oː, ɛː] can appear in the word-final position, as in to [təʊ] 'shut' (adv.), jäönae [ˈjœʏnɛɪ] 'June', deno [dəˈnoː] 'afterwards' and vörbae [vœrˈbɛː] 'past' (adv.). Only three words in his paper (outside of the list of example words for vowels) contain any of those diphthongs: togaeve [ˈtəʊˌʝɛːvə] 'to admit' (which itself contains the monophthong [ɛː]) as well as the aforementioned to [təʊ] and jäönae [ˈjœʏnɛɪ].[6] Brabantian dialects are known for both diphthongizing /eː, øː, oː/ (much as in Northern Standard Dutch) and especially monophthongizing /ɛɪ, œʏ, ɔʊ/. Many of the words in Peters' paper which contain the long open-mid monophthongs have Standard Dutch cognates with /ɛɪ, œʏ, ɔʊ/, such as the aforementioned vörbae (SD: voorbij ⓘ), äöl [œːl] 'owl' (SD: uil ⓘ) or rao [rɒː] 'raw' (SD: rauw ⓘ). Not only that, /ɛɪ/ and /œʏ/ in Standard Dutch cognates are actually of Brabantian origin (see the article Brabantse expansie on Dutch Wikipedia), with the monophthongal [ɛː, œː] being a Brabantian innovation that appeared later. Because of that, the distinction between the closing diphthongs and the monophthongs is ignored elsewhere in the article, with ⟨eː, øː, oː, ɛː, œː, ɒː⟩ being used as cover symbols for both.

- There are two additional short tense vowels [y] and [o], which appear only in a few French loanwords. They are tenser (higher and perhaps also more rounded) than the native /ʏ/ and /ʊ/ (which is much more open than the canonical value of the IPA symbol ⟨ʊ⟩ - see below). Their status as phonemes separate from the long tense /yː/ and /oː/ is unclear; Peters treats them as marginal phonemes.[7]

- /ɔə/ occurs only before alveolar consonants.[7]

- All long front unrounded vowels contrast with centering diphthongs, so that tien /tiːn/ 'ten', beer /beːr/ 'beer' and maet /mɛːt/ 'May' contrast with tieën /tiən/ 'toe', beër /beər/ 'bear' and maeët /mɛət/ 'march'.[7] The fact that this contrast occurs even before /r/ is remarkable from the Standard Dutch viewpoint, where only centering diphthongs can occur in that environment.[8] In the Ripuarian dialect of Kerkrade (spoken further east on the Germany–Netherlands border), the otherwise phonemic distinction between /iː/ and /eː/ on the one hand and /iə/ and /eə/ on the other is completely neutralized before /r/ in favor of the former, mirroring the lack of phonemic contrast in Standard Dutch.[9]

- Stressed short vowels cannot occur in open syllables. Exceptions to this rule are high-frequency words like wa /wa/ 'what' and loanwords from French.[7]

Phonetic realization

- Most of the long vowels are close to the canonical values of the corresponding IPA symbols. The open /aː/ is phonetically central [äː], whereas the monophthongal allophone of /ɒː/ is near-open [ɒ̝ː]. The short open vowels have the same quality, and the open /a, aː/ are phonological back vowels despite the symbolization.[10]

- Among the long rounded vowels, /yː, uː, ɒː/ before /t, d/ within the same syllable vary between monophthongs [yː, uː, ɒː] and centering diphthongs [yə, uə, ɒə], which often are disyllabic [ʏy.ə, ʊu.ə, ɒʊ.ə] (with the first portion realized as a closing diphthong). At least in the case of [yə] and [uə], the tongue movement may be so slight that they are sometimes better described as lip-diphthongs [yi, uɯ]. In the same environment, /øː/ can be disyllabic [øʏ.ə].[7] For the sake of simplicity, those allophones are transcribed [yə, uə, ɒə, øə] in phonetic transcription.

- /ɔə/ has the same kind of allophonic range before plosives as /yː, uː, ɒː/, varying between [ɔə ~ ɔʊ.ə ~ ɔʌ].[7]

- The short mid front vowels are rather closer than their phonemic long counterparts and considerably higher than the short back vowels of the same phonemic height, so that /ɪ, ʏ, ɛ, œ/ approach /iː, yː, eː, øː/ in articulation: [i̞, y˕, ɛ̝, œ̝].[11]

- Among the short back vowels, /u/ approaches /uː/ in articulation: [u̞], whereas /ʊ/ is both more open and more central than /oː/: [o̽], being of the same height as the phonemically open-mid /ɛ, œ/. The remaining /ɒ/ is more open than /ɛ, œ/, as stated above. Thus, the phonetic back counterpart of /ɪ, ʏ/ is /u/, whereas the phonetic back counterpart of /ɛ, œ/ is /ʊ/. The phonetically near-open /ɒ/ has no real phonetic front counterpart, as the open /a/ is phonetically central.[11]

- Among the diphthongal allophones of /eː, øː, oː/, the ending points of [eɪ] and [øʏ] are closer than the ending points of any other fronting diphthong, being more like [ei, øy]. This reinforces the phonetic difference between them and [ɛɪ, œʏ]. In addition, [əʊ] differs from (Northern) Standard Dutch [oʊ] in that it has an unrounded, central onset, rather than a rounded, centralized back one. In Belgian Standard Dutch, the corresponding vowel is monophthongal [oː].[11]

- The second elements of /aɪ/ and the [ɛɪ, œʏ] allophones of /ɛː, œː/ are more open than the monophthongs /ɪ/ and /ʏ/; in addition, the first element of /aɪ/ is open central: [ɐe, ɛe, œø].[11]

- The first element of the [ɔʊ] allophone of /ɒː/ is considerably more close and central than the /ɒ/ monophthong, being open-mid central [ɞ]; in addition, its second element is higher than /ʊ/, being closer to the canonical IPA value of the symbol ⟨ʊ⟩: [ɞʊ].[11]

- The second elements of /aʊ/ and the [əʊ] allophone of /oː/ are also higher than /ʊ/; in addition, the first element of /aʊ/ is near-open central, identical to that of /aɪ/: [ɐo̟, əo̟].[11]

- The quality of the remaining diphthongs /uɪ, iə, eə, ɛə/ is close to the canonical values of the IPA symbols used to transcribe them.[11]

Differences in transcription of the back vowels

In this article, the vowels in words oech 'you', mót 'moth' and boat 'beard' differ from the way they are transcribed by Peters (2010), who uses a narrower transcription. The differences are listed below:

| IPA symbols | Example words | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| This article | Peters 2010[11] | ||

| u | ʊ | oech | |

| uː | uː | oêch | |

| ʊ | ɔ | mót | |

| o | o | depo | |

| oː | oː | roop | |

| ɒ | ɒ | mot | |

| ɒː | ɒː | rao | |

The way those vowels are transcribed in this article reflects how they are typically transcribed in IPA transcriptions of Dutch dialects, especially Limburgish. For instance, the symbol ⟨ɔ⟩ is most typically used for the open short O in any given dialect (the one in mot, which is transcribed with ⟨ɒ⟩ in this article: /mɒt/, following Peters), not the close short O in mót /mʊt/ whenever the two are contrastive. Peters uses ⟨ʊ⟩ for the short OE in oech, but this is transcribed with ⟨u⟩ in this article (/ux/) due to the fact that the symbol ⟨ʊ⟩ is commonly used for the close short O in Dutch dialectology, which is how that vowel is written in this article.

The diphthong in mous, transcribed with ⟨ɞʊ⟩ by Peters, has also been retranscribed with a more common symbol ⟨ɔʊ⟩, though it is treated as a mere allophone of /ɒː/ in this article.

Prosody

Stress location is largely the same as in Belgian Standard Dutch. In loanwords from French, the original word-final stress is often preserved, as in kedaw /kəˈdaʊ/ 'cadeau'.[7]

Sample

The sample text is a reading of the first sentence of The North Wind and the Sun. The orthographic version is written in Standard Dutch.[12]

Phonetic transcription

[də ˈnœrdərwɪnt ʔɛn də zʊn ˈʔadən ən dɪsˈkøːsə ˈɛvə də vroːx | wi van ən twiː də ˈstɛrəkstə was | tʏn dʏ ʒyst ˈɛmant vœrˈbɛː kʊm bə nən ˈdɪkə ˈwarəmə jas aːn][5]

Orthographic version (Eye dialect)

De nörderwind en de zón hadden 'n diskeuse evve de vroog wie van hun twie de sterrekste was, tun du zjuust emmand vörbae kóm be 'nen dikke, warreme jas aan.

Orthographic version (Standard Dutch)

De noordenwind en de zon hadden een discussie over de vraag wie van hun tweeën de sterkste was, toen er juist iemand voorbij kwam met een dikke, warme jas aan.[5]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Peters (2010), p. 239.

- ↑ Peters (2010), pp. 239–240.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Peters (2010), p. 240.

- ↑ Gussenhoven (2007), pp. 336–337.

- 1 2 3 Peters (2010), p. 245.

- ↑ Peters (2010), pp. 241, 244–245.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Peters (2010), p. 242.

- ↑ Heijmans & Gussenhoven (1998).

- ↑ Stichting Kirchröadsjer Dieksiejoneer (1997), p. 18.

- ↑ Peters (2010), pp. 241–242.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Peters (2010), p. 241.

- ↑ Peters (2010), pp. 239, 245.

Bibliography

- Gussenhoven, Carlos (2007). "Wat is de beste transcriptie voor het Nederlands?" (PDF) (in Dutch). Nijmegen: Radboud University. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 March 2017. Retrieved 27 July 2022.

- Heijmans, Linda; Gussenhoven, Carlos (1998), "The Dutch dialect of Weert" (PDF), Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 28 (1–2): 107–112, doi:10.1017/S0025100300006307

- Peters, Jörg (2010), "The Flemish–Brabant dialect of Orsmaal–Gussenhoven", Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 40 (2): 239–246, doi:10.1017/S0025100310000083

- Stichting Kirchröadsjer Dieksiejoneer (1997) [1987], Kirchröadsjer Dieksiejoneer (in Dutch) (2nd ed.), Kerkrade: Stichting Kirchröadsjer Dieksiejoneer, ISBN 90-70246-34-1