| This article is part of the series on the |

| Cantonese language |

|---|

| Yue Chinese |

| Grammar |

|

| Phonology |

Standard Cantonese pronunciation is that of Guangzhou, also known as Canton, capital of Guangdong Province. Hong Kong Cantonese is related to Guangzhou dialect, and they diverge only slightly. Yue dialects in other parts of Guangdong and Guangxi provinces like Taishanese, may be considered divergent to a greater degree.

Syllables

Cantonese uses about 1,760 syllables to cover pronunciations of more than 10,000 Chinese characters. Most syllables are represented by standard Chinese characters, however a few are written with colloquial Cantonese characters. Cantonese has relatively simple syllable structure when compared to other languages. A Cantonese syllable contains one tone-carrying vowel with up to one consonant on either side.[1] The average Cantonese syllable represents 6 unique Chinese characters.

Sounds

A Cantonese syllable usually includes an initial (onset) and a final (rime/rhyme). The Cantonese syllabary has about 630 syllables.

Some like /kʷeŋ˥/ (扃), /ɛː˨/ and /ei˨/ (欸) are no longer common; some like /kʷek˥/ and /kʷʰek˥/ (隙), or /kʷaːŋ˧˥/ and /kɐŋ˧˥/ (梗), have traditionally had two equally correct pronunciations but its speakers are starting to pronounce them in only one particular way (and this usually happens because the unused pronunciation is almost unique to that word alone), making the unused sounds effectively disappear from the language; some like /kʷʰɔːk˧/ (擴), /pʰuːi˥/ (胚), /tsɵi˥/ (錐), /kaː˥/ (痂), have alternative nonstandard pronunciations which have become mainstream (as /kʷʰɔːŋ˧/, /puːi˥/, /jɵi˥/ and /kʰɛː˥/ respectively), again making some of the sounds disappear from the everyday use of the language; and yet others like /faːk˧/ (謋), /fɐŋ˩/ (揈), /tɐp˥/ (耷) have become popularly (but erroneously) believed to be made-up/borrowed words to represent sounds in modern vernacular Cantonese when they have in fact been retaining those sounds before these vernacular usages became popular.

On the other hand, new words circulate in Hong Kong which use combinations of sounds which had not appeared in Cantonese before, like /kɛt˥/ (note: /ɛːt/ was never an accepted/valid final for sounds in Cantonese and is nonstandard usage, though the final sound /ɛːt/ has appeared in vernacular Cantonese before this, /pʰɛːt˨/ – notably as the measure word of gooey or sticky substances like mud, poop, glue, chewing gum); the sound is borrowed from the English word get meaning "to understand".

Initial consonants

Initials (or onsets) refer to the 19 initial consonants which may occur at the beginning of a sound. Some sounds have no initials and are said to have null initial. The following is the inventory for Cantonese as represented in IPA:

| Labial | Dental/Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Glottal | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plain | labialized | ||||||

| Nasal | m 明 | n[upper-alpha 1] 泥 | ŋ[upper-alpha 1] 我 | ||||

| Stop | plain | p 幫 | t 端 | k 見 | kʷ[upper-alpha 2] 古 | (ʔ)[upper-alpha 3] 亞 | |

| aspirated | pʰ 滂 | tʰ 透 | kʰ 溪 | kʰʷ[upper-alpha 2] 困 | |||

| Affricate | plain | t͡s 精 | |||||

| aspirated | t͡sʰ 清 | ||||||

| Fricative | f 非 | s 心 | h 曉 | ||||

| Approximant | l[upper-alpha 1] 來 | j[upper-alpha 2] 以 | w[upper-alpha 2] 云 | ||||

Note the aspiration contrast and the lack of voicing contrast in stops.

- 1 2 3 In casual speech, many native speakers do not distinguish between /n/ and /l/, nor between /ŋ/ and the null initial.[2] Usually they pronounce only /l/ and the null initial. See the discussion on phonological shift below.

- 1 2 3 4 Some linguists prefer to analyze /j/ and /w/ as part of finals to make them analogous to the /i/ and /u/ medials in Mandarin, especially in comparative phonological studies. However, since final-heads only appear with null initial, /k/ or /kʰ/, analyzing them as part of the initials greatly reduces the count of finals at the cost of adding only four initials.

- ↑ Some linguists analyze a /ʔ/ (glottal stop) in place of the null initial when a vowel begins a sound.

Coronals' position varies from dental to alveolar, with /t/ and /tʰ/ more likely to be dental. Coronal affricates and sibilants /t͡s/, /t͡sʰ/, /s/'s position is alveolar and articulatory findings indicate they are palatalized before close front vowels /iː/ and /yː/.[3] Affricates /t͡s/ and /t͡sʰ/ also have a tendency to palatalize before central round vowels /œː/ and /ɵ/.[4] Historically, another alveolo-palatal sibilant series existed as discussed below.

Vowels and finals

Finals (or rimes/rhymes) are the part of the sound after the initial. A final is typically composed of a main vowel (nucleus) and a terminal (coda).

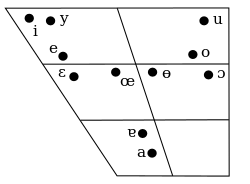

Eleven vowel analysis

As the traditionally transcribed near-close finals ([ɪŋ], [ɪk], [ʊŋ], [ʊk]) have been found to be pronounced in the mid region on acoustic findings,[5] sources like Bauer & Benedict (1997:46–47) prefer to analyze them as close-mid ([eŋ], [ek], [oŋ], [ok]) which results in eleven vowel phonemes. In this analysis, vowel length is a key contrastive feature of the vowels.

| Front | Central | Back | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| unrounded | rounded | |||||||

| short | long | short | long | short | long | short | long | |

| Close | /iː/ | /yː/ | /uː/ | |||||

| Mid | /e/ | /ɛː/ | /ɵ/ | /œː/ | /o/ | /ɔː/ | ||

| Open | /ɐ/ | /aː/ | ||||||

The following chart lists all the finals in Cantonese as represented in IPA.[6]

| Main Vowel | Syllabic Consonant | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| /aː/ | /ɐ/ | /ɛː/ | /e/ | /œː/ | /ɵ/ | /ɔː/ | /o/ | /iː/ | /yː/ | /uː/ | |||

| Monophthong | aː 沙 | ɛː 些 | œː 鋸 | ɔː 疏 | iː 詩 | yː 書 | uː 夫 | ||||||

| Diphthong | /i/ [i, y] |

aːi 街 | ɐi 雞 | ei 你 | ɵy 水 | ɔːi 愛 | uːi 會 | ||||||

| /u/ | aːu 教 | ɐu 夠 | ɛːu 掉[note] | ou 好 | iːu 了 | ||||||||

| Nasal | /m/ | aːm 衫 | ɐm 深 | ɛːm 舐[note] | iːm 點 | m̩ 唔 | |||||||

| /n/ | aːn 山 | ɐn 新 | ɛːn[note] | ɵn 準 | ɔːn 看 | iːn 見 | yːn 遠 | uːn 歡 | |||||

| /ŋ/ | aːŋ 橫 | ɐŋ 宏 | ɛːŋ 鏡 | eŋ 敬 | œːŋ 傷 | ɔːŋ 方 | oŋ 風 | ŋ̩ 五 | |||||

| Checked | /p/ | aːp 插 | ɐp 輯 | ɛːp 夾[note] | iːp 接 | ||||||||

| /t/ | aːt 達 | ɐt 突 | ɛːt[note] | ɵt 出 | ɔːt 渴 | iːt 結 | yːt 血 | uːt 沒 | |||||

| /k/ | aːk 百 | ɐk 北 | ɛːk 錫 | ek 亦 | œːk 著 | ɔːk 國 | ok 六 | ||||||

Eight vowel analysis

Some sources prefer to keep the near-close finals ([ɪŋ], [ɪk], [ʊŋ], [ʊk]) as traditionally transcribed and analyze the long-short pairs [ɛː, e], [ɔː, o], [œː, ɵ], [iː, ɪ] and [uː, ʊ] as allophones of the same phonemes, resulting in an eight vowel system instead.[7] In this analysis, vowel length is mainly allophonic and is contrastive only in the open vowels.

| Front | Central | Back | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unrounded | Rounded | Short | Long | ||

| Close | /i/ [iː, ɪ] | /y/ [yː] | /u/ [uː, ʊ] | ||

| Mid | /e/ [ɛː, e] | /ø/ [œː, ɵ] | /o/ [ɔː, o] | ||

| Open | /ɐ/ | /aː/ | |||

The following chart lists all the finals in Cantonese as represented in IPA.[7]

| Main Vowel | Syllabic Consonant | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| /aː/ | /ɐ/ | /e/ [ɛː, e] |

/ø/ [œː, ɵ] |

/o/ [ɔː, o] |

/i/ [iː, ɪ] |

/y/ [yː] |

/u/ [uː, ʊ] | |||

| Monophthong | aː 沙 | ɛː 些 | œː 鋸 | ɔː 疏 | iː 詩 | yː 書 | uː 夫 | |||

| Diphthong | /i/ [i, y] |

aːi 街 | ɐi 雞 | ei 你 | ɵy 水 | ɔːi 愛 | uːi 會 | |||

| /u/ | aːu 敎 | ɐu 夠 | ɛːu 掉[note] | ou 好 | iːu 了 | |||||

| Nasal | /m/ | aːm 衫 | ɐm 深 | ɛːm 舐[note] | iːm 點 | m̩ 唔 | ||||

| /n/ | aːn 山 | ɐn 新 | ɛːn[note] | ɵn 準 | ɔːn 看 | iːn 見 | yːn 遠 | uːn 歡 | ||

| /ŋ/ | aːŋ 橫 | ɐŋ 宏 | ɛːŋ 鏡 | œːŋ 傷 | ɔːŋ 方 | ɪŋ 敬 | ʊŋ 風 | ŋ̩ 五 | ||

| Checked | /p/ | aːp 插 | ɐp 輯 | ɛːp 夾[note] | iːp 接 | |||||

| /t/ | aːt 達 | ɐt 突 | ɛːt[note] | ɵt 出 | ɔːt 渴 | iːt 結 | yːt 血 | uːt 沒 | ||

| /k/ | aːk 百 | ɐk 北 | ɛːk 錫 | œːk 著 | ɔːk 國 | ɪk 亦 | ʊk 六 | |||

Other notes

Note: a b c d e Finals /ɛːu/,[8] /ɛːm/, /ɛːn/, /ɛːp/ and /ɛːt/ only appear in colloquial pronunciations of characters.[9] They are absent from some analyses and romanization systems.

Diphthongal ending /i/ is rounded after rounded vowels.[8] Nasal consonants can occur as base syllables in their own right and are known as syllabic nasals. The stop consonants (/p, t, k/) are unreleased ([p̚, t̚, k̚]).

When the three checked tones are separated, the stop codas /p, t, k/ are in complementary distribution with the nasal codas /m, n, ŋ/

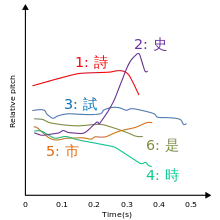

Tones

Like other Chinese dialects, Cantonese uses tone contours to distinguish words, with the number of possible tones depending on the type of final. While Guangzhou Cantonese generally distinguishes between high-falling and high level tones, the two have merged in Hong Kong Cantonese and Macau Cantonese, yielding a system of six different tones in syllables ending in a semi-vowel or nasal consonant. (Some of these have more than one realization, but such differences are not used to distinguish words.) In finals that end in a stop consonant, the number of tones is reduced to three; in Chinese descriptions, these "checked tones" are treated separately by diachronic convention, so that Cantonese is traditionally said to have nine tones. However, phonetically these are a conflation of tone and final consonant; the number of phonemic tones is six in Hong Kong and seven in Guangzhou.[10]

| Coda type | Non-stop coda | Stop coda | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tone name | dark flat (陰平) | dark rising (陰上) | dark departing (陰去) |

light flat (陽平) | light rising (陽上) | light departing (陽去) |

upper dark entering (上陰入) | lower dark entering (下陰入) | light entering (陽入) |

| Description | high level, high falling | medium rising | medium level | low falling, very low level | low rising | low level | high level | medium level | low level |

| Example | 詩, 思 | 史 | 試 | 時 | 市 | 是 | 識 | 錫 | 食 |

| Tone letter | siː˥, siː˥˧ | siː˧˥ | siː˧ | siː˨˩, siː˩ | siː˩˧ | siː˨ | sɪk̚˥ | sɛːk̚˧ | sɪk̚˨ |

| IPA diacritic | síː, sîː | sǐː | sīː | si̖ː, sı̏ː | si̗ː | sìː | sɪ́k̚ | sɛ̄ːk̚ | sɪ̀k̚ |

| Yale or Jyutping tone number |

1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 (or 1) | 8 (or 3) | 9 (or 6) |

| Yale diacritic | sī, sì | sí | si | sìh | síh | sih | sīk | sek | sihk |

For purposes of meters in Chinese poetry, the first and fourth tones are "flat/level tones" (平聲), while the rest are "oblique tones" (仄聲). This follows their regular evolution from the four tones of Middle Chinese.

The first tone can be either high level or high falling usually without affecting the meaning of the words being spoken. Most speakers are in general not consciously aware of when they use and when to use high level and high falling. Most Hong Kong speakers have merged the high level and high falling tones. In Guangzhou, the high falling tone is disappearing as well, but is still prevalent among certain words, e.g. in traditional Yale Romanization with diacritics, sàam (high falling) means the number three 三, whereas sāam (high level) means shirt 衫.[11]

The relative pitch of the tones varies with the speaker; consequently, descriptions vary from one sources to another. The difference between high and mid level tone (1 and 3) is about twice that between mid and low level (3 and 6): 60 Hz to 30 Hz. Low falling (4) starts at the same pitch as low level (6), but then drops; as is common with falling tones, it is shorter than the three level tones. The two rising tones, (2) and (5), both start at the level of (6), but rise to the level of (1) and (3), respectively.[12]

The tone 3, 4, 5 and 6 are dipping in the last syllable when in an interrogative sentence or an exclamatory sentence. 眞係? "really?" is pronounced [tsɐn˥ hɐi˨˥].

The numbers "394052786" when pronounced in Cantonese, will give the nine tones in order (Romanization (Yale) saam1, gau2, sei3, ling4, ng5, yi6, chat7, baat8, luk9), thus giving a mnemonic for remembering the nine tones.

Like other Yue dialects, Cantonese preserves an analog to the voicing distinction of Middle Chinese in the manner shown in the chart below.

| Middle Chinese | Cantonese | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tone | Initial | Nucleus | Tone Name | Tone Contour | Tone Number |

| Level | voiceless | dark level | ˥, ˥˧ | 1 | |

| voiced | light level | ˨˩, ˩ | 4 | ||

| Rising | voiceless | dark rising | ˧˥ | 2 | |

| voiced | light rising | ˩˧ | 5 | ||

| Departing | voiceless | dark departing | ˧ | 3 | |

| voiced | light departing | ˨ | 6 | ||

| Entering | voiceless | Short | upper dark entering | ˥ | 7 (1) |

| Long | lower dark entering | ˧ | 8 (3) | ||

| voiced | light entering | ˨ | 9 (6) | ||

The distinction of voiced and voiceless consonants found in Middle Chinese was preserved by the distinction of tones in Cantonese. The difference in vowel length further caused the splitting of the dark entering tone, making Cantonese (as well as other Yue Chinese branches) one of the few Chinese varieties to have further split a tone after the voicing-related splitting of the four tones of Middle Chinese.[13][14]

Cantonese is special in the way that the vowel length can affect both the rime and the tone. Some linguists believe that the vowel length feature may have roots in the Old Chinese language.

It also has two changed tones, which add the diminutive-like meaning "that familiar example" to a standard word. For example, word for "silver" (銀, /ŋɐn˩/) in a modified tone (/ŋɐn˩꜔꜒/, riɡht-facinɡ tone bars denote chanɡed tones) means "coin". They are comparable to the diminutive suffixes 兒 and 子 of Mandarin. In addition, modified tones are used in compounds, reduplications (擒擒青 /kɐm˩ kɐm˩ tʃʰɛːŋ˥/→/kɐm˩ kɐm˩꜔꜒ tʃʰɛːŋ˥/ "in a hurry") and direct address to family members (妹妹 /muːy˨ muːy˨/→/muːy˨꜖ muːy˨꜔꜒/ "sister").[15] The two modified tones are high level, like tone 1, and mid rising, like tone 2, though for some people not as high as tone 2. The high level changed tone is more common for speakers with a high falling tone; for others, mid rising (or its variant realization) is the main changed tone, in which case it only operates on those syllables with a non-high level and non-mid rising tone (i.e. only tones 3, 4, 5 and 6 in Yale and Jyutping romanizations may have changed tones).[16] However, in certain specific vocatives, the changed tone does indeed result in a high level tone (tone 1), including speakers without a phonemically distinct high falling tone.[17]

Historical change

Like other languages, Cantonese sounds are constantly changing, processes where more and more native speakers of a language change the pronunciations of certain sounds.

One shift that affected Cantonese in the past was the lost distinction between alveolar and alveolo-palatal (sometimes termed as postalveolar) sibilants which occurred during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Many Cantonese dictionaries and pronunciation guides published prior to the 1950s documented this distinction but it is no longer distinguished in any modern Cantonese dictionary.

Publications that documented this distinction include:

- Williams, S., A Tonic Dictionary of the Chinese Language in the Canton Dialect, 1856.

- Cowles, R., A Pocket Dictionary of Cantonese, 1914.

- Meyer, B. and Wempe, T., The Student's Cantonese-English Dictionary, 3rd edition, 1947.

- Chao, Y. Cantonese Primer, 1947.

The sibilants depalatalized, causing many words that were once distinct to sound the same. For comparison, modern Standard Mandarin still has this distinction, with most Cantonese alveolo-palatal sibilants corresponding to Mandarin retroflex sibilants. For instance:

| Sibilant Category | Character | Modern Cantonese | Pre-1950s Cantonese | Standard Mandarin |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unaspirated affricate | 將 | /tsœːŋ/ (alveolar) | /tsœːŋ/ (alveolar) | /tɕiɑŋ/ (alveolo-palatal) |

| 張 | /tɕœːŋ/ (alveolo-palatal) | /tʂɑŋ/ (retroflex) | ||

| Aspirated affricate | 槍 | /tsʰœːŋ/ (alveolar) | /tsʰœːŋ/ (alveolar) | /tɕʰiɑŋ/ (alveolo-palatal) |

| 昌 | /tɕʰœːŋ/ (alveolo-palatal) | /tʂʰɑŋ/ (retroflex) | ||

| Fricative | 相 | /sœːŋ/ (alveolar) | /sœːŋ/ (alveolar) | /ɕiɑŋ/ (alveolo-palatal) |

| 傷 | /ɕœːŋ/ (alveolo-palatal) | /ʂɑŋ/ (retroflex) |

Even though the aforementioned references observed the distinction, most of them also noted that the depalatalization phenomenon was already occurring at the time. Williams (1856) writes:

The initials ch and ts are constantly confounded, and some persons are absolutely unable to detect the difference, more frequently identifying the words under ts as ch, than contrariwise.

Cowles (1914) adds:

"s" initial may be heard for "sh" initial and vice versa.

A vestige of this palatalization difference is sometimes reflected in the romanization scheme used to romanize Cantonese names in Hong Kong. For instance, many names are spelled with sh even though the "sh sound" (/ɕ/) is no longer used to pronounce the word. Examples include the surname 石 (/sɛːk˨/), which is often romanized as Shek, and the names of places like Sha Tin (沙田; /saː˥ tʰiːn˩/).

The alveolo-palatal sibilants occur in complementary distribution with the retroflex sibilants in Mandarin, with the alveolo-palatal sibilants only occurring before /i/ or /y/. However, Mandarin also retains the medials, where /i/ and /y/ can occur, as can be seen in the examples above. Cantonese had lost its medials sometime ago in its history, reducing the ability for speakers to distinguish its sibilant initials.

Many modern-day younger Hong Kong speakers do not distinguish between phoneme pairs like /n/ vs. /l/ and /ŋ/ vs. null initial[2] and merge one sound into another. Examples for this include 你 /nei˨˧/ being pronounced as /lei˨˧/, 我 /ŋɔː˨˧/ being pronounced as /ɔː˨˧/. Another incipient sound change is the lost distinctions /kʷ/ vs. /k/ and /kʷʰ/ vs. /kʰ/, for example 國 /kʷɔːk˧/ being pronounced as [kɔːk̚˧].[18] Although that is often considered substandard and denounced as "lazy sounds/pronunciation" (懶音), it is becoming more common and is influencing other Cantonese-speaking regions (see Hong Kong Cantonese).

Assimilation also occurs in certain contexts: 肚餓 is sometimes read as [tʰoŋ˩˧ ŋɔː˨] not [tʰou̯˩˧ ŋɔː˨], 雪櫃 is sometimes read as [sɛːk˧ kʷɐi̯˨] not [syːt˧ kʷɐi̯˨], but sound change of these morphemes are limited to that word.

See also

Notes

- ↑ "WALS Online - Chapter Syllable Structure".

- 1 2 Yip & Matthews (2001:3–4)

- ↑ Lee, W.-S.; Zee, E. (2010). "Articulatory characteristics of the coronal stop, affricate, and fricative in Cantonese". Journal of Chinese Linguistics. 38 (2): 336–372. JSTOR 23754137.

- ↑ Bauer & Benedict (1997:28–29)

- ↑ Zee, Eric (2003), "Frequency Analysis of the Vowels in Cantonese from 50 Male and 50 Female Speakers" (PDF), Proceedings of the 15th International Congress of Phonetic Sciences: 1117–1120

- ↑ Bauer & Benedict (1997:49)

- 1 2 "Cantonese Transcription Schemes Conversion Tables - Finals". Research Centre for Humanities Computing, The Chinese University of Hong Kong. Retrieved March 5, 2019.

- 1 2 Zee, Eric (1999), "An acoustical analysis of the diphthongs in Cantonese" (PDF), Proceedings of the 14th International Congress of Phonetic Sciences: 1101–1105

- ↑ Bauer & Benedict (1997:60)

- ↑ Bauer & Benedict (1997:119–120)

- ↑ Guan (2000:474 and 530)

- ↑ Jennie Lam Suk Yin, 2003, Confusion of tones in visually-impaired children using Cantonese braille(Archived by WebCite® at

- ↑ Norman (1988:216)

- ↑ Ting (1996:150)

- ↑ Matthews & Yip (2013, section 1.4.2)

- ↑ Yu (2007:191)

- ↑ Alan C.L. Yu. "Tonal Mapping in Cantonese Vocative Reduplication" (PDF). Retrieved 27 September 2014.

- ↑ Baker & Ho (2006:xvii)

References

- Baker, Hugh; Ho, Pui-Kei (2006), Teach Yourself: Cantonese, McGraw-Hill, ISBN 0-07-142020-7

- Bauer, Robert S.; Benedict, Paul K. (1997), Modern Cantonese Phonology, Walter de Gruyter, ISBN 978-3-11-014893-0

- Francis, Alexander L. (2008), "Perceptual learning of Cantonese lexical tones by tone and non-tone language speakers", Journal of Phonetics, Elsevier, 36 (2): 268–294, doi:10.1016/j.wocn.2007.06.005

- Guan, Caihua (2000), English-Cantonese Dictionary: Cantonese in Yale Romanization, New-Asia – Yale-in-China Language Center, ISBN 978-962-201-970-6

- Matthews, Stephen; Yip, Virginia (2013), Cantonese: A Comprehensive Grammar, London: Routledge, ISBN 9781136853500

- Norman, Jerry (1988), Chinese, Cambridge Language Surveys, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-22809-1

- Ting, Pan-Hsing (1996), "Tonal Evolution and Tonal Reconstruction in Chinese", in Huang, Cheng-teh James; Li, Yen-hui Audrey (eds.), New horizons in Chinese linguistics, Springer Science & Business Media, ISBN 978-0-7923-3867-3

- Yip, Virginia; Matthews, Stephen (2001), Basic Cantonese: A Grammar and Workbook, Routledge, ISBN 978-0415193849

- Yu, Alan C. L. (2007), "Understanding near mergers: the case of morphological tone change in Cantonese" (PDF), Phonology, Cambridge University Press, 24: 187–214, doi:10.1017/S0952675707001157, S2CID 18090490

- Zee, Eric (1999), "Chinese (Hong Kong Cantonese)" (PDF), Handbook of the International Phonetic Association: A guide to the use of the International Phonetic Alphabet, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-65236-0