Electro-optic rectification (EOR), also referred to as optical rectification, is a non-linear optical process that consists of the generation of a quasi-DC polarization in a non-linear medium at the passage of an intense optical beam. For typical intensities, optical rectification is a second-order phenomenon[1] which is based on the inverse process of the electro-optic effect. It was reported for the first time in 1962,[2] when radiation from a ruby laser was transmitted through potassium dihydrogen phosphate (KDP) and potassium dideuterium phosphate (KDdP) crystals.

Explanation

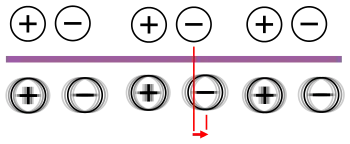

Optical rectification can be intuitively explained in terms of the symmetry properties of the non-linear medium: in the presence of a preferred internal direction, the polarization will not reverse its sign at the same time as the driving field. If the latter is represented by a sinusoidal wave, then an average DC polarization will be generated.

Optical rectification is analogous to the electric rectification effect produced by diodes, wherein an AC signal can be converted ("rectified") to DC. However, it is not the same thing. A diode can turn a sinusoidal electric field into a DC current, while optical rectification can turn a sinusoidal electric field into a DC polarization, but not a DC current. On the other hand, a changing polarization is a kind of current. Therefore, if the incident light is getting more and more intense, optical rectification causes a DC current, while if the light is getting less and less intense, optical rectification causes a DC current in the opposite direction. But again, if the light intensity is constant, optical rectification cannot cause a DC current.

When the applied electric field is delivered by a femtosecond-pulse-width laser, the spectral bandwidth associated with such short pulses is very large. The mixing of different frequency components produces a beating polarization, which results in the emission of electromagnetic waves in the terahertz region. The EOR effect is somewhat similar to a classical electrodynamic emission of radiation by an accelerating/decelerating charge, except that here the charges are in a bound dipole form and the THz generation depends on the second order susceptibility of the nonlinear optical medium. A popular material for generating radiation in the 0.5–3 THz range (0.1 mm wavelength) is zinc telluride.

Optical rectification also occurs on metal surfaces by similar effect as surface second harmonic generation. The effect is however influenced e. g. by nonequilibrium electron excitation and generally it manifests in a more complicated way.[3]

Similar to other nonlinear optical processes, optical rectification is also reported to become enhanced when surface plasmons are excited on a metal surface.[4]

Applications

Together with carrier acceleration in semiconductors and polymers, optical rectification is one of the main mechanisms for the generation of terahertz radiation using lasers.[5] This is different from other processes of terahertz generation such as polaritonics where a polar lattice vibration is thought to generate the terahertz radiation.

See also

References

- ↑ Rice et al., "Terahertz optical rectification from <110> zinc-blende crystals," Appl. Phys. Lett. 64, 1324 (1994), doi:10.1063/1.111922

- ↑ Bass et al., "Optical rectification," Phys. Rev. Lett. 9, 446 (1962), doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.9.446

- ↑ Kadlec, F., Kuzel, P., Coutaz, J. L., "Study of terahertz radiation generated by optical rectification on thin gold films," Optics Letters, 30, 1402 (2005), doi:10.1364/OL.30.001402

- ↑ G. Ramakrishnan, N. Kumar, P. C. M. Planken, D. Tanaka, and K. Kajikawa, "Surface plasmon-enhanced terahertz emission from a hemicyanine self-assembled monolayer," Opt. Express, 20, 4067-4073 (2012), doi:10.1364/OE.20.004067

- ↑ Tonouchi, M, "Cutting-edge terahertz technology," Nature Photonics 1, 97 (2007), doi:10.1038/nphoton.2007.3