| Operation Gearbox | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Arctic Campaign of the Second World War | |||||||

_(Europe_centered).svg.png.webp) Global view of Norway (Svalbard circled) | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Ernst Ullring (Norwegian Military Governor) | Dr Erich Etienne (killed 23 July 1942) | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 57 men | 18 men | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 4 killed (23 July 1942) | |||||||

Operation Gearbox (30 June – 17 September 1942) was a joint Norwegian and British operation to occupy the Arctic island of Spitsbergen during the Second World War. It superseded Operation Fritham, an expedition in May, to secure the coal mines on Spitsbergen, the main island of the Svalbard Archipelago which had failed when attacked by four German Focke-Wulf Fw 200 Condor reconnaissance bombers. The Norwegian force, with 116 long tons (118 t) of supplies, arrived by British cruiser on 2 July.

The survivors from Fritham had salvaged what equipment they could and set up camp in Barentsburg (deserted since the Operation Gauntlet evacuation and sabotage operation in August–September 1941) and sent out reconnaissance parties. The Admiralty arranged a survey flight by a Catalina flying boat from RAF Coastal Command but already knew much of what had happened, through Ultra decrypts of Luftwaffe Enigma coded wireless signals.

The reinforcements consolidated the Barentsburg defences and sent parties to attack the German weather party at Longyearbyen on 12 July, only to find that they had departed three days earlier. The German airstrip was blocked and on 23 July, a Ju 88, carrying an experienced crew and two senior officials, was shot down while flying low over the landing ground. In Operation Gearbox, Norwegian sovereignty had been asserted, no casualties had been suffered, the German plan to send another weather party had been thwarted and preparations had begun for Operation Gearbox II.

Background

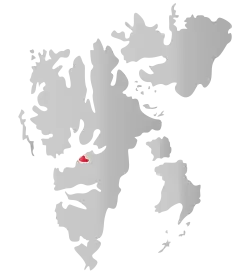

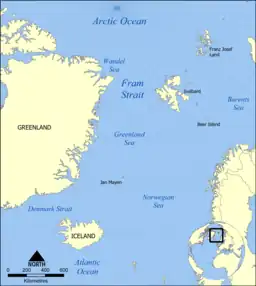

Svalbard

The Svalbard Archipelago is in the Arctic Ocean 650 mi (1,050 km) from the North Pole. The islands are mountainous, with permanently snow-covered peaks, some glaciated; there are occasional river terraces at the bottom of steep valleys and some coastal plains. In winter, the islands are covered in snow and the bays ice over. Spitsbergen Island has several large fiords along its west coast and Isfjorden is up to 10 mi (16 km) wide. The Gulf Stream warms the waters and the sea is ice-free during the summer. Settlements were established at Longyearbyen and Barentsburg in inlets along the south shore of Isfjorden, in Kings Bay (Quade Hock) further north along the coast and in Van Mijenfjorden (Lowe Sound) to the south.[1] The settlements attracted colonists of different nationalities and the treaty of 1920 neutralised the islands and recognised the mineral and fishing rights of the participating countries. Before 1939, the population consisted of about 3,000, mostly Norwegian and Russian people, who worked in the mining industry. Drift mines were linked to the shore by overhead cable tracks or rails and coal dumped over the winter was collected by ship after the summer thaw. By 1939 production was about 500,000 long tons (510,000 t) a year, split between Norway and Russia.[1]

Signals intelligence

The British Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS) based at Bletchley Park housed a small industry of code-breakers and traffic analysts. By June 1941, the German Enigma machine Home Waters (Heimish) settings used by surface ships and U-boats quickly could be read. On 1 February 1942, the Enigma machines used in U-boats in the Atlantic and Mediterranean were changed but German ships and the U-boats in Arctic waters continued with the older Heimish (Hydra from 1942, Dolphin to the British). By mid-1941, British Y-stations were able to receive and read Luftwaffe W/T transmissions and give advance warning of Luftwaffe operations. In 1941, interception parties code-named Headaches were embarked on warships and from May 1942, computers sailed with the cruiser admirals in command of convoy escorts, to read Luftwaffe W/T signals which could not be intercepted by land stations in Britain. The Admiralty sent details of Luftwaffe wireless frequencies, call signs and the daily local codes to the computers. Combined with their knowledge of Luftwaffe procedures, the computers could give fairly accurate details of German reconnaissance sorties and sometimes predicted attacks twenty minutes before they were detected by radar.[2] In February 1942, the German Beobachtungsdienst (B-Dienst, Observation Service) of the Kriegsmarine Marinenachrichtendienst (MND, Naval Intelligence Service) broke Naval Cypher No 3 and was able to read it until January 1943.[3]

Naval operations, 1940–1941

The Germans left the Svalbard islands alone during the invasion of Norway in 1940. Apart from a few Norwegians taking passage on Allied ships, little changed; wireless stations on the islands continued to broadcast weather reports.[4] From 25 July to 9 August 1940, the cruiser Admiral Hipper sailed from Trondheim to search the area from Tromsø to Bear Island and Svalbard to intercept British ships returning from Petsamo but found only a Finnish freighter.[5] On 12 July 1941, the Admiralty was ordered to assemble a force of ships to operate in the Arctic, in co-operation with the USSR, despite objections from Admiral John (Jack) Tovey, commander of the Home Fleet, who preferred to operate further south, where there were more targets and better air cover.[6]

Rear-admirals Philip Vian and Geoffrey Miles flew to Polyarnoe and Miles established a British military mission in Moscow.[6] Vian reported that Murmansk was close to German held territory, that its air defences were inadequate and that the prospects of offensive operations on German shipping were poor. Vian was sent to look at the west coast of Spitsbergen, the main island of Svalbard, which was mostly ice-free and 450 mi (720 km) from northern Norway, to assess its potential as a base. The cruisers HMS Nigeria, Aurora and two destroyers, departed Iceland on 27 July but Vian judged the apparent advantages of Spitsbergen as a base to be exaggerated.[7] The force closed on the Norwegian coast twice and each time was discovered by Luftwaffe reconnaissance aircraft.[8]

Operation Gauntlet

As Operation Dervish, the first Arctic convoy, was assembling in Iceland, Vian sailed with Force A for Svalbard on 19 August in Operation Gauntlet. Norwegian and Russian civilians were to be evacuated using the same two cruisers, with five destroyer escorts, an oiler and RMS Empress of Canada, a troop transport carrying 645 men, mainly Canadian infantry.[lower-alpha 1] The expedition landed at Barentsburg to sabotage the coal industry, evacuate the Norwegian and Soviet civilians and commandeer any shipping that could be found. About 2,000 Russians were taken to Archangelsk in Empress of Canada, escorted by one of the cruisers and the three destroyers, which rendezvoused with the rest of Force A off Barentsburg on 1 September.[8] Normal business was kept up at the Barentsburg wireless station by the Norwegian Military Governor Designate, Lieutenant Ragnvald Tamber; three colliers sent from the mainland were hijacked along with the seal ship MS Selis, the ice-breaker SS Isbjørn, a tug and two fishing boats. The Canadian landing parties embarked on 2 September and the force sailed for home the next day, with 800 Norwegian civilians and the prizes.[10] The two cruisers diverted towards the Norwegian coast to hunt for German ships and early on 7 September, in stormy weather and poor visibility found a German convoy off Porshanger near the North Cape. The cruisers sank the training ship Bremse but two troop transports, with 1,500 men aboard, escaped. Nigeria was damaged, thought to have hit a wreck but the naval force reached Scapa Flow on 10 September.[11][10][lower-alpha 2]

Operation Bansö, 1941–1942

After Operation Gauntlet (25 August – 3 September 1941) the British had expected the Germans to occupy Svalbard as a base for attacks on Arctic convoys. The Germans were more interested in meteorological data, the Arctic being the origin of much of the weather over Western Europe. By August 1941, the Allies had eliminated German weather stations on Greenland, Jan Mayen Island, Bear Island (Bjørnøya) and the civil weather reports from Spitsbergen. The Germans used weather reports from U-boats, reconnaissance aircraft, trawlers and other ships but these were too vulnerable to attack. The Kriegsmarine and the Luftwaffe surveyed land sites for weather stations in the range of sea and air supply, some to be manned and others automatic. Wettererkundungsstaffel 5 (Wekusta 5) part of Luftflotte 5, was based at Banak in northern Norway. The Heinkel He 111s and Junkers Ju 88s of Wekusta 5 ranged over the Arctic Ocean, past Spitsbergen and Jan Mayen towards Greenland; the experience gained made the unit capable of the transporting and supplying manned and automatic weather stations.[13]

After the wireless on Spitsbergen had mysteriously ceased transmission in early September, German reconnaissance flights from Banak discovered the Canadian demolitions, burning coal dumps and saw one man, a conscientious objector who had refused to leave, waving to them. Dr Erich Etienne, a former Polar explorer, commanded an operation to install a manned station on the islands but with winter imminent, time was short. Advent Bay (Adventfjorden) was chosen for its broad valley, making a safer approach for aircraft; its subsoil of alluvial gravel was acceptable for a landing ground. The south-east orientation of the high ground did not impede wireless communication with Banak and the settlement of Longyearbyen (Longyear Town) was close by. A north-west to south-east airstrip about 1,800 by 250 yd (1,650 by 230 m) was marked out, which was firm when dry and hard when frozen but liable to become boggy after rain or the spring thaw. The Germans used the Hans Lund Hut as a control room and wireless station, the Inner Hjorthamn Hut to the south-east being prepared as a substitute. The site received the code-name Bansö (from Banak and Spitsbergen Öya), ferry flights of men, equipment and supplies began on 25 September. He 111, Ju 88 and Ju 52 pilots gained experience of landing on soft ground, cut with ruts and boulders.[14]

The British followed events from Bletchley Park through Ultra, made easier by German routine use of radio communication. Four British minesweepers en route from Archangelsk were diverted to investigate and reached Isfjorden on 19 October. A Wekusta 5 aircraft crew spotted the ships as they prepared to land and the thirty men at Bansö quickly were flown to safety by the aircraft and two Ju 52 transport aircraft. Bansö was deserted when the British arrived but some code books were recovered; when the ships left, the Germans returned. After 38 supply flights Dr Albrecht Moll and three men arrived to spend the winter transmitting weather reports. On 29 October 1941, Hans Knoespel and five weathermen were installed by the Kriegsmarine at Lilliehöökfjorden, a branch of Krossfjord in the north-western Spitsbergen.[15][lower-alpha 3] Landing aircraft was riskier in winter, when the landing ground or an ice-covered bay was frozen solid, because soft snow on top could pile up in front of the wheels of the aircraft and jerk it to a stop or prevent it from reaching take-off speed. The blanket of snow could also cover holes, into which a wheel could fall, potentially to damage the undercarriage or propeller.[17]

The Moll party at Bansö called for aircraft when the weather was adequate and after making low and slow passes, to check the landing ground for obstructions, the pilot decided whether to land.[17] On 2 May 1942, the apparatus for an automatic weather station, a thermometer, barometer, transmitter and batteries arrived at Banak, in a box named Krote (toad) by the aircrew. As soon as weather permitted, it was to be flown to Bansö and the Moll party brought back. It took until 12 May for a favourable weather report to reach Banak and a He 111 and a Ju 88 were sent with supplies and the technicians to install the Krote. The aircraft reached Bansö at 5:45 a.m. and after a careful examination of the ground, the Heinkel pilot eventually landed, keeping its tail well up out of the snow. The main wheels quickly packed snow in front of them and the aircraft almost nosed over. The ten crew and passengers joined the ground party, who welcomed them warmly, having been alone for six months; the Ju 88 pilot was warned off by a flare and returned to Banak.[18]

Operation Fritham

.jpg.webp)

On 30 April 1942, Isbjørn and Selis (Lieutenant H. Øi Royal Norwegian Navy) and about twenty crewmen sailed from Greenock with a Norwegian landing party of 60 men, accompanied by three British liaison officers.[19] Each ship carried a 20 mm Oerlikon anti-aircraft gun but none of the party had been trained in their use. Major Amherst Whatman, a Polar explorer and signals specialist, repaired and operated the wireless set but it broke down on the journey to Iceland and was not reliable for the rest of the voyage. The ships hugged the Polar ice, with little risk of being seen by Luftwaffe aircraft, once north-east of Jan Mayen.[20] The ships reached Svalbard on 13 May and entered Isfjorden at 8:00 p.m. Grønfjorden (Green Fjord or Green Harbour to the British) was covered in ice up to 4 ft (1.2 m) thick. The ice breaking was delayed until after midnight on 14 May and parties were sent to scout Barentsburg on the east shore and the Finneset peninsula.[21] The scouting parties found no-one but took until 5:00 p.m. to get back, by when Isbjørn had cut a long channel in the ice but was still well short of Finneset. A Ju 88 flew along Isfiorden, also at 5:00 p.m. but Sverdrup insisted on making for the landing stage at Barentsburg to unload quicker.[21]

At 8:30 p.m., four Fw 200 Condor long-range reconnaissance bombers appeared; the valley sides were so high that the bombers arrived without warning and the third bomber hit Isbjørn which sank immediately and Selis was soon set on fire.[22] Thirteen men were killed, including Sverdrup and Godfrey, nine men were wounded, two mortally. The equipment in Isbjørn, arms, ammunition, food, clothes and the wireless had been lost. Barentsburg was only a few hundred yards across the ice and plenty of food was found because it was the Svalbard custom to stock up before winter. The local swine herd had been slaughtered during Gauntlet and the arctic cold had preserved the meat; wild duck could be plundered for eggs and an infirmary was also found, still stocked with dressings for the wounded. Ju 88 and He 111 bombers returned on 15 May but the survivors took cover in mine shafts.[22] The fitter men at Barentsburg tended the wounded and lay low when the Luftwaffe was around. Lieutenant Ove Roll Lund sent parties south to Sveagruva in Van Mijenfjorden (Lowe Sound) and to reconnoitre the Germans in Advent Bay around the airstrip at Bansö.[23]

Prelude

Plan

After Convoy PQ 16 (21–30 May 1942) Air-Chief Marshal Philip Joubert, the AOC Coastal Command, mindful of the lack of aircraft carriers and the limited help available from the Soviet Air Forces (Voyenno-Vozdushnye Sily, VVS), suggested that a flying-boat base be established on Spitsbergen. Because of the remoteness of Svalbard, the inevitable frequent grounding of aircraft during bad weather and the troubles encountered by Operation Fritham, the Admiralty rejected the idea. Joubert also suggested basing flying boats in north Russia and eight Catalinas from 210 Squadron and 240 Squadron were sent to fly from the Kola Inlet and Lake Lakhta for Convoy PQ 17 (27 June – 10 July) the next convoy operation. Joubert also proposed to send a force of torpedo-bombers to Vaenga but this was vetoed by the Admiralty for lack of aircraft.[24]

At the end of June, Glen delivered his report to the Admiralty, describing the calamity of 14 May, the strength of the German party at Bansö and the prospects of achieving the objectives of Fritham by sending reinforcements. Glen predicted that the German weather party would be replaced by an automatic weather-reporting device and that the Luftwaffe would increase the number of weather reconnaissance flights over the Arctic. The Admiralty decided to press on; Fritham was to be terminated and replaced by Operation Gearbox. To avoid another disaster, the occupation of Spitsbergen was to remain under the command of Norwegian government forces but the Navy would be responsible for delivering supplies and the trips were to be synchronised with outbound PQ convoys. The cruiser HMS Manchester and the destroyer HMS Eclipse were to begin Gearbox by carrying 57 Norwegian reinforcements (Lieutenant Gudim and 2nd Lieutenant K. Knudsen) and 116.6 long tons (118.5 t) of stores to Spitsbergen.[25]

Catalina flights, 25–27 June

The Admiralty sent Glen and the pilot, Flight Lieutenant D. E. (Tim) Healy, to brief Vice-Admiral S. S. Bomham-Carter, commander of the 18th Cruiser Squadron at Greenock in Scotland and were asked to photograph the Spitsbergen coast from about 100 ft (30 m) to simulate the view from Manchester's bridge. Healy and Glen described the pier at Barentsburg, which was silted up but had a crane, said that ice floes might float past in a southerly breeze and Healy agreed to take some vertical photographs of the pier. Glen and Croft were due to return to Spitsbergen on 26 June and were going to signal to Manchester when it arrived with Eclipse on 1 July, with a report of the latest Luftwaffe activity. P-Peter took off from Sullom Voe at 1:21 p.m. and headed for Iceland for another ice reconnaissance, being shot at by British trawlers on the way. At 6:32 p.m. the crew made course for Greenland, eventually seeing pack ice through the fog. The Catalina flew into Scoresby Sound and the crew photographed 200 nmi (370 km; 230 mi) northwards to Cape Brewster, turned for Iceland at 11:30 p.m. and flew in clear weather almost to the island before the fog closed in again, landing at Akureyri at 2:35 a.m. on 26 June[26]

The ice and weather reports were transmitted and P-Peter took off at 11:50 p.m. for Jan Mayen, thence to Spitsbergen, making landfall at 8:10 a.m. The crew descended to 100 ft (30 m) to take photographs in clear weather then turned east for Bell Sound and photographed Van Mijenfjorden (Lowe Sound) a prospective anchorage for tankers, examining Sveagruva, which seemed unoccupied. The crew took pictures of the coast to Cape Linné, Green Harbour and Barentsburg, made contact with Fritham Force and then photographed the pier, the navigator hanging out of the port blister with a camera, held fast by a colleague. Healy landed P-Peter, deposited Glen and Croft into a boat and took off for Advent Bay to check on the Germans. There was no snow around Longyearbyen but tracks could be seen near the airstrip, which were followed to an aircraft near a hut, with piles of equipment and a lorry nearby. The Catalina gunners got ready and engaged what turned out to be a Ju 88 with 1,500 rounds of machine-gun fire and photographed the attack with ciné and still cameras, smoke coming out of the tail of the Ju 88. The Catalina crew dropped a message to the ground party as they flew back and set a middling course for Shetland and Iceland, ignoring the itinerary for Jan Mayen. At 6:32 p.m. a weather signal revealed that Sullom Voe was too foggy and the crew set course for Iceland, eventually to see Cape Langanaes and coast-crawl to land at Eyjafjörður at 11:40 p.m.[27][lower-alpha 4]

Luftwaffe, 14 June – 3 July

The Moll party at Bansö had reported the British flight of 26 May and on 12 June reported that the landing ground was dry enough for a landing attempt. A Ju 88 flew to the island and landed but damaged its propellers as it taxied, stranding the crew and increasing the German party to 18 men. Luftwaffe aircraft were flown to Spitsbergen each day but the crews were warned off. The Germans thought about using floatplanes but the east end of Isfjorden and Advent Bay were too full of drifting ice and the idea was dropped. In the midnight sun (20 April – 22 August) as mid-summer approached, the ice in the west of the fiord near the Allied positions cleared faster than that by the Germans in the east end.[29] The Germans reported the Catalina attack on the Ju 88 on 27 June, which had left it a write-off and claimed to have damaged the British aircraft with return fire. On 30 June, the party sent a message that the airstrip was dry enough for Junkers Ju 52 aircraft to land and supply flights were resumed. The aircraft were watched by a Norwegian party which had gone on an abortive expedition to destroy the German headquarters at the Hans Lund Hut. On clear days, the German pilots flew direct over the mountains; when visibility was poor, they took the coast route past Barentsburg.[30]

Operation Gearbox

28 June – 5 July

Manchester and Eclipse left the Clyde for Scapa Flow on 25 June with Operation Gearbox, the Norwegian party to reinforce Fritham Force, embarked. The ships arrived at Seidisfjord in Iceland on 28 June and met the pilot and navigator of Catalina P-Peter, who had flown the special reconnaissance to Spitsbergen, to be briefed. The cruiser delayed departure until 30 June to appear part of the escort force of PQ 17, if sighted by a U-boat near Jan Mayen. The Polar ice formed an inverted funnel, with the left side, south of Jan Mayen, curving north-east to just north of Isfjorden and the right side, south of Bear Island, curving north-west to the southern entrance to Isfjorden. The ships steamed northwards up the funnel and then turned east to approach Isfjorden from the west. Eclipse was refuelled on 1 July, during a thick fog and at 8:38 a.m. on 2 July, the bridge crews sighted the fiord in excellent visibility.[31]

Off Barentsburg at noon, the ships received a welcome signal from Fritham Force that a Luftwaffe aircraft flew a daily reconnaissance at 3:00 a.m. and sometimes another at 2:00 p.m. but no sea or ground forces had appeared.[31] In poor weather German aircraft followed the coast past Barentsburg, which had led to the discovery of Isbjørn and Selis. The pier was too silted for mooring; the ships kept their engines running and the crews at anti-aircraft stations. Ship's boats, motorboats, a motor dinghy, a pinnace, cutters and whalers made 121 round trips in six hours, unloading the Norwegians and the supplies, including short-wave wireless, 40 mm Bofors anti-aircraft guns, skis, sledges and other Arctic warfare equipment. Croft, Øi and eleven other men of the Fritham party were taken on board and by 7:00 p.m. the ships had departed. The men ashore quickly eliminated any sign of the visit, cranes were pulled back from the quay, boats hidden and the stores camouflaged.[32]

Unlike Sverdrup, whose brief was primarily economic, Ullring had been ordered to re-claim Norwegian sovereignty over the Svalbard islands. He found a bombed settlement with frozen livestock scattered around, under a pall of smoke from the smouldering coal dumps. To the dismay of the Gearbox party, their machine-guns were found to have no ammunition belts, leaving only the 20 mm Oerlikons and M2 Browning machine-guns. On 3 July, an aircraft was heard flying along Isfjorden and then back again an hour later, thought to have landed at Longyearbyen; later a Ju 52 was seen following the same route. By 5 July four Oerlikons and four Brownings had been installed and the gun crews rehearsed.[32]

6–14 July

On 12 July a supply trip from 210 Squadron was to deliver the missing Colt ammunition belts to Barentsburg, before conducting a reconnaissance of the Barents Sea to search for survivors of Convoy PQ 17, which has lost 24 ships. On departing Barentsburg, the Catalina was to fly 100 nmi (190 km; 120 mi) east of Sørkapp (South Cape) to Hopen (Hope Island) and then east along the Polar ice as far as possible and then turn south to north Russia. After resting, the crew was to fly back to the Polar ice where they had left off and then fly east again to 78° north, half way between Novaya Zemlya and Franz Joseph Land, thence to return to Russia via Cape Nassau. Catalina N-November (Flt/Lt G. G. Potier) departed Sullom Voe at 1:59 p.m. on 13 July and reached Barentsburg at 12:25 a.m. on 14 July, only to be hit by machine-gun fire in the tail and wing by mistake. The Catalina landed for ten minutes to off-load supplies and then flew on to Hopen at 200 ft (61 m) under the cloud.[33][lower-alpha 5]

15–29 July

Once the Colt parts had been delivered, Ullring had one mounted in a cutter and on 15 July, set off in the midnight sun with ten men, to attack the Germans at Longyearbyen in Advent Bay. The last Germans on Spitsbergen, including the weather-reporting party that had been in residence since late 1941, had been flown back to Norway on 9 July.[30] The Germans had gone but the Ju 88 shot up on 1 July was still there, the wireless transmitter and other equipment were operational, stores were plentiful and the buildings used by the party were in good condition, suggesting that the German departure was not permanent. The Krote near the shore at Hjorthamn was found, dismantled and returned to Barentsburg for shipment to Britain and a party with two Colt and two Browning machine guns was left behind to guard the airstrip. A Ju 88 was sent from Norway to investigate the cessation of transmissions from the Krote on 20 July; the crew saw that the base had been destroyed and found themselves under machine-gun fire from the Norwegians. The party at Sveagruva heard the bomber pass overhead and assumed that the base at Banak had been alerted.[34]

On 21 July, a Ju 88 flying over Green Harbour was fired on by the Oerlikon gunners; the port engine trailed smoke and a hole appeared in one of the wing tips. German records showed that the crew judged the landing ground was too boggy for safe landings in the summer. As a precaution against a surprise landing, the ground markers were removed by the Norwegians, several trenches were dug and obstacles were strewn over the strip.[34] Another transmitter and some stores were found in Adventdalen; Ullring sailed south to Bellsund (Bell Sound), Van Mijenfjorden (Lowe Sound) and Braganza Bay to deliver arms to the Fritham Force party and take nine of them to reinforce Barentsburg. At Banak, Dr Erich Etienne, who had supervised the weather data operation and Major Vollrath Wibel arranged a reconnaissance flight to Spitsbergen. A Ju 88 of Wetterkundungsstaffel 5 (Weather Squadron 5) flew the sortie over Advent Bay on 23 July to reconnoitre the extent of the Allied interference with the Krote. As the aircraft flew low towards Hjorthamn and made a steep turn; Niks Langbak, a Selis gunner, fired ten rounds from a machine-gun and the bomber crashed and exploded; two rounds had hit one of the engines. The area around Hiorthfjellet had several coal transporter cables and the Ju 88 might have collided with one after being hit; the crew were buried and code books salvaged from the wreckage.[35]

30 July–August

The loss of an experienced crew and the passengers led the Germans to send more flights but they were able only to see that the Bansö airstrip had been occupied and that they lacked the forces to re-capture the site. The Norwegians had recovered signals information and code books and had suffered no more casualties; Whatman and the wireless operators were sending copious amounts of information to the Admiralty and on 29 July, Catalina P-Peter flew Tetanus anti-toxin and other items to Operation Gearbox, then returned with Glen on 30 July to visit the Admiralty for discussions about the forthcoming Operation Gearbox II and Convoy PQ 18. Glen was satisfied that the Norwegian hold on Isfjorden and Green harbour was sufficiently secure to use it as a seaplane base.[36] At the beginning of August, Ullring took a party of nine men north along the coast and to Kongsfjorden (Kingsfjord) in the cutter to look for another German weather station but found only a footprint. On 20 August, a U-boat entered Isfjorden and bombarded shore installations in Green Harbour and Advent Bay with its deck gun. At Barentsburg, the Norwegians returned fire from the cutter armed with the Colt machine-gun, which was moored at the pier and with an Oerlikon emplaced on the rise beyond the village, forcing the U-boat to fire from longer range; the Norwegians again suffered no casualties.[37]

Aftermath

Analysis

The remainder of Fritham Force at Barentsburg was consolidated by the reinforcements of Operation Gearbox and its sequels, a weather station was set up and wireless contact with the Admiralty regained. Ullring reported the oversight with the Colt machine-guns, arranged for Catalina supply flights, provided weather and sighting reports, protected Wharman and his apparatus for research into the ionosphere and prepared to attack German weather stations wherever they could be found.[38] The survivors of Operation Fritham provided excellent local knowledge and with the arrival of the Gearbox personnel, could do more than subsist and dodge attacks by German aircraft. The flight of Catalina N-Nuts to Spitsbergen on 13 July with the Colt parts and other supplies, thence to north Russia to search for PQ 17 survivors, informed the British naval authorities in Murmansk that the Barents Sea was free of ice. Many survivors were rescued and ships sheltering at Novaya Zemlya were escorted safely to port. Planning began at the Admiralty for Operation Gearbox II, the sequel to Gearbox and with Operation Orator, part of the forthcoming Convoy PQ 18.[39]

Subsequent operations

Operation Gearbox II

After the calamity of Convoy PQ 17, Joubert re-submitted a torpedo-bomber proposal, which was accepted and took place as Operation Orator.[24] During PQ 18 (2–21 September 1942) Force P, the fleet oilers RFA Blue Ranger and RFA Oligarch and four destroyer escorts sailed on 3 September for Spitsbergen and anchored in Van Mijenfjorden (Lowe Sound), as an advanced refuelling party. From 9 to 13 September, destroyers were detached from PQ 18 to refuel.[40] Operation Gearbox II began with another supply run by the cruiser HMS Cumberland, Eclipse and four more destroyer escorts, which arrived on 17 September, with 130 long tons (130 t) of supplies and a party of Norwegian troops (Lieutenant-Colonel Albert Tornerud and Military Governor in place of Ullring); HMS Sheffield arrived the next day with another 110 long tons (110 t) of stores.[41]

The ships kept their engines running again and the crews were closed up for anti-aircraft action, the ships unloading and departing in six hours. Two Husky teams with forty dogs, three Bofors guns, two Fordson tractors, boats, wireless equipment and winter supplies were delivered.[41] Healy took part in Operation Orator and left Grasnaya on 25 September to return to Scotland via Svalbard, to pick up Glen. Bad weather forced a return to Murmansk and at 1:29 p.m., about 70 nmi (130 km; 81 mi) out from the coast, Healy was killed in an engagement with a Ju 88.[42] On 19 October, HMS Argonaut and two destroyers delivered supplies and a Norwegian vessel made the voyage in November.[43][44] On 7 June 1943, Cumberland, HMS Bermuda and two destroyers sailed from Iceland and landed men and supplies at Spitsbergen on 10 July.[45]

Notes

- ↑ Commander: Brigadier Arthur Potts, 527 Canadians, 25 Norwegians (Captain Aubert), 93 British including 57 Royal Engineers.[9]

- ↑ After the war it was surmised that Nigeria had hit a mine.[12]

- ↑ On 24 August 1942, the Knoespel group was repatriated by U-435, after being attacked by a party from Operation Gearbox.[16]

- ↑ Healy hitched a lift on a trawler to Seidisfiord, to rendezvous with Manchester and Eclipse, which had reached Iceland on 29 June. Healy briefed the bridge crew that the ice edge ran from Jan Mayen at 42° to the latitude of 72° then turned north, leaving the route to Spitsbergen ice-free. Sea fog offered cover from Luftwaffe aircraft, which usually flew over Isfjorden from 2–5:00 a.m., before the ships were due to arrive. Healy sailed back to the Catalina and took off again for Sullom Voe at 8:35 a.m. on 1 June.[28]

- ↑ After turning south for Russia, five lifeboats with about forty men were spotted; the crew sent goodwill messages by signal lamp and dropped food and cigarettes in a Mae West. The crew flew on, over the White Sea to Lakhta airfield near Murmansk to report the survivors, who were rescued by corvettes sent from Archangelsk.[33]

Footnotes

- 1 2 Schofield & Nesbit 2005, pp. 61–62.

- ↑ Hinsley 1994, pp. 141, 145–146.

- ↑ Hinsley 1994, pp. 126, 135.

- ↑ Schofield & Nesbit 2005, p. 62.

- ↑ Roskill 1957, p. 260.

- 1 2 Woodman 2004, pp. 10–11.

- ↑ Roskill 1957, p. 488.

- 1 2 Woodman 2004, pp. 10–11, 35–36.

- ↑ Stacey 1956, p. 304.

- 1 2 Roskill 1957, p. 489.

- ↑ Woodman 2004, pp. 35–36.

- ↑ Woodman 2004, p. 36.

- ↑ Schofield & Nesbit 2005, pp. 63–64.

- ↑ Schofield & Nesbit 2005, pp. 64–67, 95.

- ↑ Schofield & Nesbit 2005, p. 67.

- ↑ Schofield & Nesbit 2005, p. 95.

- 1 2 Schofield & Nesbit 2005, pp. 95–96.

- ↑ Schofield & Nesbit 2005, pp. 96–99.

- ↑ Schofield & Nesbit 2005, pp. 63, 94–95.

- ↑ Schofield & Nesbit 2005, pp. 94–95.

- 1 2 Schofield & Nesbit 2005, pp. 105–106.

- 1 2 Schofield & Nesbit 2005, pp. 105–110.

- ↑ Schofield & Nesbit 2005, pp. 110–112.

- 1 2 Richards & Saunders 1975, pp. 80–81.

- ↑ Schofield & Nesbit 2005, p. 150.

- ↑ Schofield & Nesbit 2005, pp. 151–157.

- ↑ Schofield & Nesbit 2005, pp. 157–162.

- ↑ Schofield & Nesbit 2005, pp. 162–163.

- ↑ Schofield & Nesbit 2005, pp. 134–135.

- 1 2 Schofield & Nesbit 2005, pp. 166–167.

- 1 2 Schofield & Nesbit 2005, pp. 162–164.

- 1 2 Schofield & Nesbit 2005, pp. 162–166.

- 1 2 Schofield & Nesbit 2005, p. 170.

- 1 2 Schofield & Nesbit 2005, pp. 171–173.

- ↑ Schofield & Nesbit 2005, pp. 173–174.

- ↑ Schofield & Nesbit 2005, pp. 174–176.

- ↑ Schofield & Nesbit 2005, pp. 166–173, 190.

- ↑ Hutson 2012, p. 125.

- ↑ Schofield & Nesbit 2005, pp. 168–171.

- ↑ Roskill 1962, pp. 280–283.

- 1 2 Schofield & Nesbit 2005, pp. 177, 189.

- ↑ Richards & Saunders 1975, pp. 84–85.

- ↑ Roskill 1962, p. 287.

- ↑ Hutson 2012, pp. 126–127.

- ↑ Roskill 1960, p. 59.

References

Books

- Hinsley, F. H. (1994) [1993]. British Intelligence in the Second World War: Its Influence on Strategy and Operations. History of the Second World War (2nd rev. abr. ed.). London: HMSO. ISBN 978-0-11-630961-7.

- Hutson, H. C. (2012). Arctic Interlude: Independent to North Russia (6th ed.). Online: CreateSpace Independent Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4810-0668-2.

- Richards, Denis; Saunders, H. St. G (1975) [1954]. Royal Air Force 1939–1945: The Fight Avails. History of the Second World War, Military Series. Vol. II (pbk. ed.). London: HMSO. ISBN 978-0-11-771593-6. Retrieved 1 June 2018.

- Roskill, S. W. (1957) [1954]. Butler, J. R. M. (ed.). The War at Sea 1939–1945: The Defensive. History of the Second World War, United Kingdom Military Series. Vol. I (4th ed.). London: HMSO. OCLC 881709135. Retrieved 1 June 2018.

- Roskill, S. W. (1962) [1956]. Butler, J. R. M. (ed.). The War at Sea 1939–1945: The Period of Balance. History of the Second World War, United Kingdom Military Series. Vol. II (3rd ed.). London: HMSO. OCLC 174453986. Retrieved 1 June 2018.

- Roskill, S. W. (1960). Butler, J. R. M. (ed.). The War at Sea 1939–1945: The Offensive, Part I: 1st June 1943 – 31st May 1944. History of the Second World War, United Kingdom Military Series. Vol. III. London: HMSO. OCLC 570500225.

- Schofield, Ernest; Nesbit, Roy Conyers (2005). Arctic Airmen: The RAF in Spitsbergen and North Russia 1942 (2nd ed.). London: W. Kimber. ISBN 978-1-86227-291-0.

- Stacey, C. P. (1956) [1955]. Six Years of War: The Army in Canada, Britain and the Pacific. Official History of the Canadian Army in the Second World War. Vol. I (online 2008, Dept. of National Defence, Directorate of History and Heritage ed.). Ottawa: Authority of the Minister of National Defence. OCLC 317352934. Archived from the original on 1 April 2019. Retrieved 1 June 2018.

- Woodman, Richard (2004) [1994]. Arctic Convoys 1941–1945. London: John Murray. ISBN 978-0-7195-5752-1.

Websites

- Andre Verdenskrig på Svalbard (Svalbard Museum) Archived 24 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine

Further reading

- Lawson, S. H. (2001). "D/S Isbjørn". Warsailors.com. Retrieved 1 June 2018.

- Levy, J. (2001). Holding the Line: The Royal Navy's Home Fleet in the Second World War (pdf) (PhD thesis). University of Wales Swansea (Swansea University). OCLC 502551844. Docket uk.bl.ethos.493885. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- Morison, S. E. (1956). The Atlantic Battle Won, May 1943 – May 1945. History of United States Naval Operations in World War II. Vol. X (online ed.). Boston, Massachusetts: Little, Brown and Co. OCLC 59074150. Retrieved 1 June 2018.

- Ryan, J. F. (1996). The Royal Navy and Soviet Seapower, 1930–1950: Intelligence, Naval Cooperation and Antagonism (pdf) (PhD thesis). University of Hull. OCLC 60137725. Docket uk.bl.ethos.321124. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- Schiøtz, Eli (2007). Offiser og krigsfange: Norske offiserer i tysk krigsfangenskap – fra oberst Johannes Schiøtz' dagbok [Officer and Prisoner of War: Norwegian Officers in German War Captivity: From Colonel John Schiøtz's Diary] (in Norwegian) (1st ed.). Kjeller: Genesis forlag. ISBN 978-82-476-0336-9.

- Sebag-Montefiore, Hugh (2001) [2000]. Enigma: The Battle for the Code (4th, pbk. Phoenix ed.). London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 0-75381-130-8.