| |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Western Front of the First World War | |||||||||

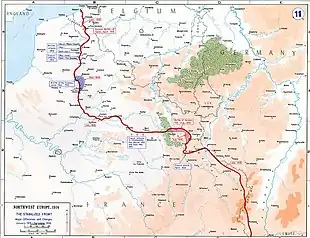

New front line after Operation Alberich | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| Operation Alberich | |

|---|---|

| Part of the Western Front | |

| Type | Strategic withdrawal |

| Location | Noyon and Bapaume salients |

| Planned | 1916–1917 |

| Planned by | Field Marshal Rupprecht von Bayern |

| Commanded by | Quartermaster-General Erich Ludendorff |

| Objective | Retirement to the Hindenburg Line |

| Date | 9 February 1917 – 20 March 1917 |

| Executed by | Army Group Rupprecht of Bavaria (Heeresgruppe Kronprinz Rupprecht von Bayern) |

| Outcome | Success |

Operation Alberich (German: Unternehmen Alberich) was the code name of a German military operation in France during the First World War.[lower-alpha 1] Two salients had been formed during the Battle of the Somme in 1916 between Arras and Saint-Quentin and from Saint-Quentin to Noyon. Alberich was planned as a strategic withdrawal to new positions on the shorter and more easily defended Hindenburg Line (German: Siegfriedstellung). General Erich Ludendorff was reluctant to order the withdrawal and hesitated until the last moment.

The retirement took place between February 9 and March 20, 1917, after months of preparation. The German retreat shortened the Western front by 25 mi (40 km). The retirement to the chord of the Bapaume and Noyon salients shortened the Western Front, providing 13 to 14 extra divisions for the German strategic reserve being assembled to defend the Aisne front against the Franco-British Nivelle Offensive, preparations for which were barely concealed.

Background

Winter 1916–1917

Soon after taking over from General der Infanterie Erich von Falkenhayn as head of the Supreme Army Command (Oberste Heeresleitung) at the end of August 1916, Generalfeldmarshall Paul von Hindenburg and his deputy General der Infanterie Erich Ludendorff, the Erster Generalquartiermeister (First Quartermaster General) ordered the building of a new defensive line, east of the Somme battlefront, from Arras to Laon. Ludendorff was unsure as to whether retreating to the Siegfriedstellung (Hindenburg Line) was desirable, since it might diminish the morale of German soldiers and civilians.[1]

An offensive was considered as an alternative, if enough reserves could be assembled in the New Year and a staff study suggested that seventeen divisions might be made available but that this was far too few to have decisive effect in the west. Alternatives, such as a shorter withdrawal, were also canvassed but the lack of manpower made the decision to retire unavoidable, since even with reinforcements from the Eastern Front, the German army in the west (Westheer) numbered only 154 divisions against 190 Allied divisions, many of which were larger. A move back to the Hindenburg Line (Siegfriedstellung) would shorten the front by 25–28 mi (40–45 km) and require 13 to 14 fewer divisions to hold.[2]

German debates

German army thinking about a withdrawal to the Siegfriedstellung changed during the winter of 1916–1917 and comprised positive and negative reasons. At first it was seen by OHL as a last resort, if pressure on the Somme front became overwhelming. After the Central Powers' success in the Battle of Bucharest (November 28 – December 6, 1916) and the beginning of the winter lull in France, optimism at OHL that the retreat was unnecessary rose but was then deflated by the French attack at Verdun on December 15. During January 1917 the resumption of unrestricted U-boat warfare on 1 February 1917 offered the possibility of driving Britain out of the war. To win in the west, the German armies would have only to avoid defeat; a retirement to the Siegfriedstellung would give the Westheer a big defensive advantage.[3]

A move back to the Siegfriedstellung would generate reserves by shortening the front and the defensive strength of the new positions, built in depth, on reverse positions, behind wide belts of barbed wire and studded with machine-gun nests, would allow divisions to hold a wider frontage. Before the British and French could attack the new defences, they would have to rebuild the communications between the Somme and Siegfriedstellung, comprehensively destroyed by the Germans before the retirement. The Germans planned to waste the land; villages demolished, bridges blown, roads and railways dug up, wells tainted and the population carried off. The British and French armies would have to repeat the preparations for another offensive, after the retirement made preparations to resume the offensive on the Somme redundant. Every day's delay of an Entente offensive in France gave more time for the U-boat offensive to work; even if the Franco-British managed to attack, the Westheer expected to defeat the attempt.[4]

General der Infanterie Fritz von Below, commander of the 1st Army (1. Armee/Armeeoberkommando 1/A.O.K. 1), had opposed a withdrawal to avoid a blow to the morale of the men who had fought to defend the Somme front. Subordinate commanders on the Somme doubted the ability of their men to withstand another offensive. The commander of the XIV Reserve Corps, Generalleutnant Georg Fuchs, reported that morale was low and that the defences were in a deplorable state, positions near the Ancre being nothing more than flooded shell holes. Hermann von Kuhl, chief of staff of Army Group Rupprecht of Bavaria (Heeresgruppe Kronprinz Rupprecht von Bayern) was persuaded by Fuchs and others to advocate a move back to the Siegfriedstellung and on 4 February, the Kaiser, Wilhelm II ordered that the intervening ground be devastated and the retirement to begin on 9 February; Below and the 2nd Army commander, General der Kavallerie Georg von der Marwitz (since 17 December 1916), had been overruled by a consensus of their leaders and subordinates.[5]

Prelude

Crown Prince Rupprecht

Rupprecht, Crown Prince of Bavaria, commander of Heeresgruppe Kronprinz Rupprecht von Bayern, comprising the 1st Army, 2nd, 6th and 7th armies (from the Somme front to Flanders) had preferred a deeper retreat to fortifications incorporating cities like Lille and Cambrai, to deter an Entente attack but OHL judged this impractical for lack of manpower. Rupprecht also opposed the intention to turn the ground in the Noyon Salient into a wasteland when the final demolitions to scorch the earth began on 16 March, because of the damage to the prestige of the German Empire and the deleterious effects on the discipline of his troops.[6] The demolitions made a desert of 579 sq mi (1,500 km2) of territory and Rupprecht contemplated resignation, then relented, for fear that it might suggest a rift between Bavaria and the rest of Germany.[7][8]

Operations on the Ancre

From 11 January to 13 March 1917, the British Fifth Army attacked the German 1st Army positions in the Ancre river valley, on the northern flank of the Somme battlefield of 1916. The Action of Miraumont (17–18 February), Capture of the Thilloys (25 February – 2 March) and the Capture of Irles (10 March) took place before the main German withdrawal began.[9] British attacks had taken place against exhausted German troops holding poor defensive positions left over from the fighting in 1916; some German troops had low morale and showed an unusual willingness to surrender. British attacks in the action of Miraumont and anticipation of further attacks led Rupprecht on 18 March to order a withdrawal.[10]

The 1st Army withdrew of about 3 mi (4.8 km) on a 15 mi (24 km) front of the 1st Army to the Riegel I Stellung from Essarts to Le Transloy on 22 February. The retirement caused some surprise to the British, despite the interception of wireless messages from 20 to 21 February.[11] A second German withdrawal took place on 11 March, during a preparatory British bombardment and was not noticed by the British until the night of 12/13 March. Patrols found Riegel I Stellung empty between Bapaume and Achiet le Petit and strongly held on either flank. A British attack on Bucquoy at the north end of Riegel I Stellung on the night of 13/14 March was a costly failure. German withdrawals on the Ancre spread south, beginning with a retirement from the salient around St Pierre Vaast Wood.[12]

Unternehmen Alberich

German withdrawal

Alberich began on 9 February 1917 in the area to be abandoned. Railways and roads were dug up, trees were felled, water wells were polluted, towns and villages were demolished and many land mines and other booby traps were planted.[13] About 125,000 able-bodied French civilians in the region were transported to work elsewhere in occupied France, while children, mothers and the elderly were left behind with minimal rations. On 4 March, Général Louis Franchet d'Espèrey, commander of Groupe d'armées du Nord (GAN, Northern Army Group), advocated an attack while the Germans were preparing to retreat. Robert Nivelle, Commander-in-Chief of the French armies since December 1916, approved only a limited attack to capture the German front position; a potential opportunity to turn the German withdrawal into a rout was lost.[14] The withdrawal took place from 16–20 March, with a retirement of about 25 mi (40 km), giving up more French territory than that gained by the Allies from September 1914 until the beginning of the operation.[15]

British operations

During the German withdrawal the British Third Army and Fifth Army followed up and conducted the Capture of Bapaume, 1917 (17 March) and the Occupation of Péronne (18 March).[16]

Aftermath

Analysis

By evacuating the Noyon and Bapaume salients, the Germans shortened their front by 25 mi (40 km). Fourteen fewer German divisions were needed for line holding; Allied plans for their spring offensive were seriously disrupted.[17] The operation is considered to have been a propaganda disaster for Germany because of the scorched-earth policy but is also thought to be one of the shrewdest defensive operations of the war. During periods of fine weather in October 1916, British reconnaissance flights had reported new defences being built far behind the Somme front; on 9 November a formation of eight photographic reconnaissance aircraft and eight escorts reported a new line of defences from Bourlon Wood north to Quéant, Bullecourt, the Sensée river, Héninel and the German third line near Arras. Two other lines closer to the front were observed as they were dug (Riegel I Stellung and Riegel II Stellung) from Ablainzevelle to the west of Bapaume and Roquigny, with a branch from Achiet-le-Grand to Beugny and Ytres.[18]

In 2004, James Beach wrote that some authorities hold that British aerial reconnaissance failed to detect the construction of the Hindenburg Line or the German preparations for the troop withdrawal. Evidence of German intentions was collected but German deception measures caused unremarkable information to be gleaned from intermittent air reconnaissance. Frequent bad flying weather over the winter and the precedent of new German defences being built behind existing fortifications, during the Somme battle, led British military intelligence to misinterpret the information. In late December 1916, reports from witnesses led the British and French to send air reconnaissance sorties further to the south and in mid-January 1917, British intelligence concluded that a new line was being built from Arras to Laon. By February, the line was known to be near completion and by 25 February, local withdrawals on the British Fifth Army front in the Ancre valley and prisoner interrogation led the British to anticipate a gradual German withdrawal to the new line.[19]

The first intimation of a German withdrawal occurred when British patrols probing German outposts towards Serre, found them unoccupied. The British began a slow follow-up but unreadiness, the decrepitude of the local roads and the German advantage of falling back on prepared lines behind rearguards of machine-gunners, meant that the Germans completed an orderly withdrawal. The new defences were built on a reverse slope with positions behind the defences, from which artillery observers could see the front position, experience having showed that infantry equipped with machine-guns needed a field of fire only a few hundred yards/meters deep. Unfortunately for the Germans, General Ludwig von Lauter and Colonel Kramer from OHL ignored the new thinking and in much of the new position, they put artillery observation posts in the front line or in front of it and the front position was on forward slopes, near crests or at the rear of long reverse slopes.[20]

Notes

- ↑ In Wagner's opera cycle Der Ring des Nibelungen, Alberich, the chief of the Nibelungen, a race of dwarfs, is an antagonist.

Footnotes

- ↑ Sheldon 2009, pp. 1–4.

- ↑ Sheldon 2009, pp. 4–5.

- ↑ Spears 1939, p. 118; Boff 2018, pp. 148–149.

- ↑ Boff 2018, pp. 149–150.

- ↑ Boff 2018, pp. 148–149.

- ↑ Boff 2018, p. 150.

- ↑ Watson 2015, p. 328.

- ↑ Sheldon 2009, p. 5.

- ↑ James 1990, p. 15.

- ↑ Bean 1982, p. 60.

- ↑ Bean 1982, p. 60; Falls 1992, pp. 94–110.

- ↑ Falls 1992, pp. 94–110.

- ↑ Simkins, Jukes & Hickey 2003, p. 111.

- ↑ Rickard 2001.

- ↑ Simkins, Jukes & Hickey 2003, p. 119.

- ↑ James 1990, p. 16.

- ↑ Simkins, Jukes & Hickey 2003, p. 112.

- ↑ Jones 2002, pp. 317–318.

- ↑ Beach 2004, pp. 190–195.

- ↑ Wynne 1976, pp. 138–139.

References

Books

- Bean, C. E. W. (1982) [1933]. The Australian Imperial Force in France, 1917. The Official History of Australia in the War of 1914–1918. Vol. IV (11th ed.). Canberra: Australian War Memorial. ISBN 978-0-7022-1710-4. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- Boff, J. (2018). Haig's Enemy: Crown Prince Rupprecht and Germany's War on the Western Front (1st ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-967046-8.

- Falls, C. (1992) [1940]. Military Operations France and Belgium 1917: The German Retreat to the Hindenburg Line and the Battles of Arras. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. Vol. I (repr. Imperial War Museum and Battery Press ed.). London: HMSO. ISBN 978-0-89839-180-0.

- James, E. A. (1990) [1924]. A Record of the Battles and Engagements of the British Armies in France and Flanders 1914–1918 (repr. London Stamp Exchange ed.). Aldershot: Gale & Polden. ISBN 978-0-948130-18-2.

- Jones, H. A. (2002) [1928]. The War in the Air, Being the Story of the Part played in the Great War by the Royal Air Force. Vol. II (Imperial War Museum and Naval & Military Press ed.). London: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-1-84342-413-0. Retrieved 4 May 2015.

- Simkins, P.; Jukes, G.; Hickey, M. (2003). The First World War: The War to End All Wars. Oxford: Osprey. ISBN 978-1-84176-738-3.

- Sheldon, J. (2009). The German Army at Cambrai. Barnsley: Pen & Sword. ISBN 978-1-84415-944-4.

- Spears, Sir Edward (1939). Prelude to Victory (1st ed.). London: Jonathan Cape. OCLC 459267081.

- Watson, A. (2015) [2014]. Ring of Steel: Germany and Austria-Hungary at War, 1914–1918 (2nd pbk. ed.). London: Penguin Random House UK. ISBN 978-0-141-04203-9.

- Wynne, G. C. (1976) [1939]. If Germany Attacks: The Battle in Depth in the West (Greenwood Press, NY ed.). Connecticut: Faber. ISBN 978-0-8371-5029-1.

Theses

- Beach, James Michael (2004). British Intelligence and the German Army 1914–1918. london.ac.uk (PhD thesis). London: University of London. OCLC 500051492. EThOS uk.bl.ethos.416459. Retrieved 4 December 2013.

Websites

- Rickard, J. (2001). "Robert Georges Nivelle (1856–1924), French General". History of War. Archived from the original on 9 March 2009. Retrieved 30 January 2009.

Further reading

Books

- Foerster, Wolfgang, ed. (2012) [1939]. Die Kriegsführung im Frühjahr 1917 [Warfare in the Spring of 1917]. Der Weltkrieg 1914 bis 1918 Die militärischen Operationen zu Lande [The World War 1914–1918 Military Operations on Land]. Vol. XII. Berlin: Verlag Ernst Siegfried Mittler & Sohn. OCLC 719270698. Retrieved 16 November 2013 – via Die digitale Oberösterreichische Landesbibliothek.

- Foley, R. T. (2007). "The Other Side of the Wire: The German Army in 1917". In Dennis, P.; Grey, G. (eds.). 1917: Tactics, Training and Technology. Loftus, NSW: Australian History Military Publications. pp. 155–178. ISBN 978-0-9803-7967-9.

- Haig, D. (2009) [1907]. Cavalry Studies: Strategical and Tactical (General Books ed.). London: Hugh Rees. ISBN 978-0-217-96199-8. Retrieved 23 March 2014.

- Harris, J. P. (2009) [2008]. Douglas Haig and the First World War (repr. ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-89802-7.

- Nicholls, J. (2005). Cheerful Sacrifice: The Battle of Arras 1917. Barnsley: Pen and Sword Books. ISBN 978-1-84415-326-8.

- Sheldon, J. (2015). The German Army in the Spring Offensives 1917: Arras, Aisne & Champagne. Barnsley: Pen & Sword Military. ISBN 978-1-78346-345-9.

- Simpson, A. (2006). Directing Operations: British Corps Command on the Western Front 1914–18. Stroud: Spellmount. ISBN 978-1-86227-292-7.

- Smith, L.; Audoin-Rouzeau, Stéphane; Becker, A. (2003). France and the Great War, 1914–1918. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-66631-2.

- Whitehead, R. J. (June 2018). The Other Side of the Wire: With the XIV Reserve Corps: The Period of transition 2 July 1916 – August 1917. Vol. III (1st ed.). Warwick: Helion. ISBN 978-1-911512-47-9.

Encyclopaedias

- Tucker, S. C.; Roberts, P. M., eds. (2005). The Encyclopaedia of World War I: A Political, Social and Military History. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-85109-420-2.

- The Times History of the War. Vol. XII. London. 1914–1921. OCLC 475617679. Retrieved 6 November 2013.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|work=ignored (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)