| Ooceraea biroi | |

|---|---|

| |

| Pinned Ooceraea biroi worker | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Hymenoptera |

| Family: | Formicidae |

| Genus: | Ooceraea |

| Species: | O. biroi |

| Binomial name | |

| Ooceraea biroi (Forel, 1907) | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Ooceraea biroi, the clonal raider ant,[1] is a queenless clonal ant in the genus Ooceraea (recently transferred from the genus Cerapachys).[2][3] Native to the Asian mainland, this species has become invasive on tropical and subtropical islands throughout the world.[4] Unlike most ants, which have reproductive queens and mostly nonreproductive workers, all individuals in a O. biroi colony reproduce clonally via thelytokous parthenogenesis.[5][6] Like most dorylines, O. biroi are obligate myrmecophages and raid nests of other ant species to feed on the brood.[5][7]

Description

Clonal raider ants are small, about 2 mm long, but relatively stocky. Like many former cerapachyines, O. biroi is heavily armored, with the short, thick antennae which give the old subfamily its name (from Greek, keras/κέρας, meaning horn and pachys/παχυς, meaning thick). The other defining characteristic of the former Cerapachyinae, a row of teeth over the pygidium (last visible abdominal segment), is very small in O. biroi and difficult to see. O. biroi can be distinguished from many other former cerapachyines by the combination of highly reduced or nonexistent eyes, rectangular head, and a distinct postpetiole.[8]

Cyclic life history

Like many myrmecophagous ants, O. biroi exhibits synchronized oviposition and cyclic behavior, shifting between a reproductive phase and a foraging phase.[9][10] The reproductive phase begins when a cohort of larvae pupate and all the adults in the colony activate their ovaries. Thelytokously produced eggs are then laid synchronously after about four days and develop for roughly 10 days while the adults remain within the nest, cleaning and tending the eggs and pupae. Eggs hatch roughly two weeks into the reproductive phase, and then a few days later, the foraging phase begins with emergence of new adults from the pupae. Adults forage for the next two weeks, raiding the nests of other ant species to bring back food for the larvae. The cycle completes with the pupation of the new larval cohort and the resumption of the reproductive phase.[10]

Genetics and genomics

Parthenogenesis is a natural form of reproduction in which growth and development of embryos occur without fertilisation. Thelytoky is a particular form of parthenogenesis in which the development of a female individual occurs from an unfertilized egg. Automixis is a form of thelytoky, but different kinds of automixis are seen. The kind of automixis relevant here is one in which two haploid products from the same meiosis combine to form a diploid zygote. Because O. biroi can be very easily maintained in laboratory conditions, it has attracted attention as a potential model organism for studying the molecular biology of sociality.[11] Laboratory maintenance is made easy by the clonality of the species; a few individuals placed in an airtight box and given ant brood as food can be grown up into many large colonies.[5] Clonal reproduction is achieved by automixis with central fusion (see diagram), as is common in the Hymenoptera, yet unlike most clonal Hymenoptera, loss of heterozygosity is extraordinarily slow.[11] The upshot of this is that offspring are almost genetically identical to the parent, allowing nearly complete control over the genotype of experimental subjects. Finally, since O. biroi colonies are queenless and all workers reproduce, generation time is about two months (the developmental time of a single individual), rather than many years as is the case for most ant species.[10][11]

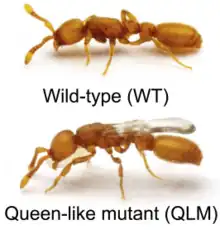

It has been also reported that clonal raider ants have a supergene on their 13 chromosome which normally is present heterozygotically and only expressed in homozygous clonal raiders which will possess more queen-like characteristics such having small wing buds, laying twice as many eggs and engaging in social parasitism where the care of their eggs is left to the heterozygous workers.[12][13][14]

References

- ↑ taxonomy. "Taxonomy browser (root)". www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2021-11-28.

- ↑ M. L. Borowiec (2016). "Generic revision of the ant subfamily Dorylinae (Hymenoptera, Formicidae)". ZooKeys (608): 1–280. doi:10.3897/zookeys.608.9427. PMC 4982377. PMID 27559303.

- ↑ S.G. Brady; B.L. Fisher; T.R. Schultz P.S. Ward (2014). "The rise of army ants and their relatives: diversification of specialized predatory doryline ants". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 14: 93. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-14-93. PMC 4021219. PMID 24886136.

- ↑ J. K. Wetterer; D. J. C. Kronauer; M. L. Borowiec (2012). "Worldwide spread of Cerapachys biroi (Hymenoptera: Formicidae: Cerapachyinae". Mymecological News. 17: 1–4.

- 1 2 3 K. Tsuji; K. Yamauchi (1995). "Production of female by parthenogenesis in the ant, Cerapachys biroi". Insectes Sociaux. 42 (3): 333–336. doi:10.1007/bf01240430. S2CID 42223499.

- ↑ F. Ravary; P Jaisson (2004). "Absence of individual sterility in thelytokous colonies of the ant Cerapachys biroi Forel (Formicidae, Cerapachyinae)". Insectes Sociaux. 51: 67–73. doi:10.1007/s00040-003-0724-y. S2CID 25607639.

- ↑ Hölldobler, Bert; Wilson, Edward O. (1990). The Ants. Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-04075-9.

- ↑ antweb.org

- ↑ D.J.C. Kronauer (2009). "Recent advances in army ant biology (Hymenoptera: Formicidae)". Myrmecological News. 12: 51–55.

- 1 2 3 F. Ravary; P. Jaisson (2002). "The reproductive cycle of thelytokous colonies of Cerapachys biroi Forel (Formicidae, Cerapachyinae)". Insectes Sociaux. 49 (2): 114–119. doi:10.1007/s00040-002-8288-9. S2CID 33510603.

- 1 2 3 Oxley, P.R.O.; Ji, L.; Fetter-Pruneda, I.; McKenzie, S.K.; Li, C.; Hu, H.; Zhang, G.; Kronauer, D.J.C. (2014). "The Genome of the Clonal Raider Ante Cerapachys biroi". Current Biology. 24 (4): 451–458. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2014.01.018. PMC 3961065. PMID 24508170.

- ↑ Trible, Waring; Chandra, Vikram; Lacy, Kip D.; Limón, Gina; McKenzie, Sean K.; Olivos-Cisneros, Leonora; Arsenault, Samuel V.; Kronauer, Daniel J.C. (March 2023). "A caste differentiation mutant elucidates the evolution of socially parasitic ants". Current Biology. 33 (6): 1047–1058.e4. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2023.01.067. ISSN 0960-9822. PMC 10050096. PMID 36858043.

- ↑ Callier, Viviane (2023-05-08). "A Mutation Turned Ants Into Parasites in One Generation". Quanta Magazine. Retrieved 2023-05-19.

- ↑ "First Known 'Social Chromosome' Found". www.science.org. Retrieved 2023-06-13.

External links

Media related to Cerapachys biroi at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Cerapachys biroi at Wikimedia Commons