Odolany | |

|---|---|

Neighbourhood and City Information System area | |

Apartment buildings at Hubalczyków Street, located in Odolany, in 2018. | |

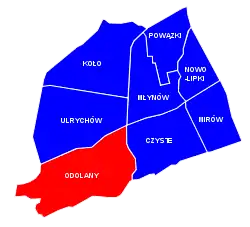

Location of Odolany within the district of Wola, in accordance to the City Information System. | |

| Coordinates: 52°13′09.52″N 20°56′32.06″E / 52.2193111°N 20.9422389°E | |

| Country | |

| Voivodeship | Masovian |

| City county | Warsaw |

| District | Wola |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Area code | +48 22 |

Odolany[lower-alpha 1] is a neighbourhood, and an area of the City Information System, in the city of Warsaw, Poland, located within the district of Wola.[1]

Name

The name Odolany comes from a Polish male first name, Odolan. The form Odolany indicates that it was a family name and means that the area belonged to the descendants of Odolan.[2]

A neighbourhood of Odolany in the city of Szczecin was named after the neighbourhood in Warsaw. It was named as such after 1946, when, in the aftermath of World War II, it was incorporated from Germany into Poland.[3][4]

Characteristics

Education and science

Odolany hosts the Institute of Computer Science of the Polish Academy of Sciences, which conducts research on computer science.[5] There are also two private universities in Odolany: the Higher School of Rehabilitation, and the Edward Wiszniewski Higher School of Economics.[6]

Public transit and transportation infrastructure

The Warszawa Wola railway station, on railway line no. 20, is located near Prymasa Tysiąclecia Avenue. The station is operated by Polish State Railways.[7][8]

The central and southern portion of Odolany is covered by railway infrastructure, including the railway tracks, as well as technical, administrative and employee housing buildings of Polish State Railways.[9] Also in Odolany is the Warszawa Szczęśliwice motive power depot.[10]

History

The village was settled on the road leading from Warsaw to Błonie (currently Połczyńska Street). In 1431, the village became the property of the Collegiate Church of St. John the Baptist.[11][12] In 1528, the village was noted to have an area of 5 lans, which equals around 85 hectares (0.85 km² or 0.328 sq mi). In 1789, in Odolany were located 18 houses.[11]

The Yellow Tavern (Polish: Żółta Karczma) was located in Odolany between what is now Ordona Street and Prądzyńskiego Street. It was a popular meeting place for nobility to engage in political discussions, debates, and vote buying, during the royal elections in Wola. During the elections, which were held between 1572 and 1791, the members of nobility would vote to chose the leader of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. The building was destroyed during the Second World War.[13][14]

In 1845 in Odolany were built standard-gauge (1,435 mm) railway tracks of the Warsaw–Vienna Railway (today part of the railway line no. 1).[15][16]

In 1890, Fort Ve-Shcha "Odolany" was built in the village as part of the inner circle of the series of fortifications of the Warsaw Fortress, built around Warsaw by the Russian Empire. Most of the fort has been destroyed, with its concrete bunker being the only remaining part of the building.[17][18]

Between 1901 and 1903 in Odolany were built Russian gauge (1520 mm) railway tracks of the Warsaw–Kalisz Railway, which connected Warszawa Kaliska railway station in Warsaw with Kalisz railway station in Kalisz. The section of railway tracks in Odolany was located between the Warszawa Kaliska and Błonie railway stations.[11][19] The section included the railway viaduct, located near current Armatnia Street, which, built in 1902, was probably the first railway object in the Russian Empire to use reinforced concrete in its construction. In 1914, the railroad was rebuilt into standard-gauge (1,435 mm) railway tracks, though it consisted mostly of the provisional structures. After 1918, the railroad was rebuilt as permanent structure. The railway viaduct was not rebuilt with the standard-gauge and was disconected from the railway network. Today, it is the only remaining element of the original Warsaw–Kalisz Railway line in Odolany.[20]

On 1 April 1916, most of Odolany was incorporated into the city of Warsaw.[21] Its remaining western portion eventually became a gromada (village assembly) in the gmina (municipality) of Blizne. It was incorporated into Warsaw on 5 May 1951.[22]

Between 1922 and 1929, at the southern boundary of Odolany was built the Warszawa Szczęśliwice motive power depot.[11][23]

.jpg.webp)

On 1 September 1939 Nazi Germany invaded Poland, beginning the Second World War.[24] The city of Warsaw capitulated to the invading forces on 28 September 1939, becoming part of the occupied territories of the General Government.[25] In the night of 7 to 8 October 1942, in the Operation Wieniec, sapper squadrons of the Home Army targeted the rail infrastructure near Warsaw, detonating bombs which destroyed railway tracks and derailed several trains. In retaliation, on 16 October 1942, the occupation forces executed 50 prisoners of the Pawiak prison by hanging. Among them, 9 prisoners were hanged near the railway tracks near Warszawa Szczęśliwice and several others at the Wola Gallows near Mszczonowska Street.[26]

Between 5 and 12 August 1944, in the Wola massacre, the occupant forces systematically killed between 40,000 and 50,000 Polish people who lived in the district of Wola, including the neighborhood of Odolany.[27][28]

The neighbourhood begun developing after the end of the Second World War in 1945. At the main road of Odolany, Jana Kazimierza Street, was built the factory of the Ludwik Waryński Construction Machines Factories (Polish: Warszawskie Zakłady Maszyn Budowlanych im. Ludwika Waryńskiego). Additionally, between Ordona Street, Kasprzaka Street, and Prymasa Tysiąclecia Avenue operated the General Świerczewski Precise Products Factory (Polish: Fabryka Wyrobów Precyzyjnych im. gen. Świerczewskiego).[29]

In the 2010s, in the areas owned by companies VIS and Bumar-Waryński, around the Jana Kazimierza Street and Ordona Street, were built neighbourhoods of multifamily residential apartment buildings.[9]

Administrative boundaries

Odolany is located within the south–western portion of the district of Wola in the city of Warsaw, Poland. It is a City Information System area. To the north, its border is determined by Wolska Street, Połczyńska Street, and railway line no. 509; to the east by railway line no. 20 and Prymasa Tysiąclecia Avenue; to the south by railway line no. 1; to the west by the railway tracks of the Warszawa Szczęśliwice motive power depot, the railway tracks between Warszawa Główna Towarowa railway station and Warszawa Szczęśliwice motive power depot, and Dźwigowa Street.[1]

Odolany borders Ulrychów to the north, Młynów to the north–east, Czyste to the east, Old Ochota to the south–east, Szczęśliwice and Old Włochy to the south, and New Włochy and Jelonki Południowe to the west. Its southern and western boundaries form the border of the district of Wola, bordering districts of Ochota to the south, Włochy to the south–west, and Bemowo to the west.[1]

Citations

Notes

References

- 1 2 3 "Dzielnica Wola". zdm.waw.pl (in Polish). Archived from the original on 2022-11-28. Retrieved 2023-05-11.

- ↑ Kwiryna Handke: Dzieje Warszawy nazwami pisane. Warsaw: Museum of Warsaw, 2011, p. 299. ISBN 978-83-62189-08-3. (in Polish).

- ↑ Tadeusz Białecki (editor): Encyklopedia Szczecina. Szczecin: Szczecińskie Towarzystwo Kultury. p. 644. ISBN 978-83-94275-0-0. (in Polish)

- ↑ Hieronim Rybicki: Powstanie i działalność władzy ludowej na zachodnich i północnych obszarach Polski: 1945–1949, Poznań, 1976. (in Polish)

- ↑ "Institute of Computer Science of the Polish Academy of Sciences". nauka-polska.pl. Archived from the original on 2003-12-01. Retrieved 2023-05-11.

- ↑ Ula Olczak (21 February 2022). "Odolany – mieszkania. Dlaczego warto zamieszkać w tej lokalizacji?". obido.pl (in Polish). Archived from the original on 8 May 2023. Retrieved 11 May 2023.

- ↑ "Warszawa Wola". atlaskolejowy.net (in Polish). Archived from the original on 2017-03-13. Retrieved 2023-05-11.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ↑ "Kolej bliżej pasażera - nowe przystanki i nowe nazwy na sieci kolejowej - PKP Polskie Linie Kolejowe S.A". plk-sa.pl (in Polish). Archived from the original on 2018-09-18. Retrieved 2023-05-11.

- 1 2 Michał Radkowski: Odolany za wieloma torami. In: Gazeta Stołeczna, p. 12, 27 July 2018. (in Polish)

- ↑ Załącznik nr 1 do SIWZ GOZ-351-4/13 Archived 2015-08-19 at the Wayback Machine. Warsaw: Szybka Kolej Miejska. 22 April 2014. (in Polish).

- 1 2 3 4 Encyklopedia Warszawy. Warsaw: Polish Scientific Publishers PWN, 1994, p. 565. ISBN 83-01-08836-2. (in Polish)

- ↑ Adam Wolff: Wola w czasach książąt mazowieckich. In: Dzieje Woli. Warsaw: Polish Scientific Publishers PWN, 1974, p. 44. (in Polish)

- ↑ Agnieszka Rataj (26 December 2018). "Odolany – kompletny przewodnik po osiedlu". morizon.pl (in Polish). Archived from the original on 5 May 2023. Retrieved 11 May 2023.

- ↑ "Historia Odolan i warszawskiej Woli" (in Polish). 27 March 2022. Archived from the original on 5 May 2023. Retrieved 11 May 2023.

- ↑ Marian Chlewski: 130 lat Kolei Warszawsko-Wiedeńskiej. In: Młody Technik. issue 11–12, p. 83–87, 1975. Wydawnictwo Nasza Księgarnia. (in Polish).

- ↑ Michał Jerczyński, Stanisław Koziarski, Andrzej Paszke: 150 lat Drogi Żelaznej Warszawsko-Wiedeńskiej. Warsaw: Centralna Dyrekcja Okręgowa Kolei Państwowych, 1995. ISBN 8390408805. (in Polish)

- ↑ Stanisław Łagowski: Cytadela Warszawska. Pruszków: Oficyna Wydawnicza Ajaks, 2010, p. 99–100. ISBN 978-83-62046-23-2. (in Polish).

- ↑ Lech Królikowski, Twierdza Warszawa. Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Bellona, 2002. ISBN 8311093563. (in Polish).

- ↑ W. Leszkowicz: Kolej Kaliska. Budowa. Eksploatacja. Znaczenie dla przemysłowego rozwoju. In: R. Kołodziejczyl: Studia z dziejów kolei żelaznych w Królestwie Polskim (1840-1914). Warsaw, 1970.

- ↑ Zbigniew Tucholski: Paraboliczny wiadukt sklepiony Drogi Żelaznej Warszawsko-Kaliskiej przy ul. Armatniej w Warszawie – jedna z dwóch najstarszych na terenie Warszawy budowli inżynieryjnych o konstrukcji betonowej. In: Ochrona Zabytków. January 2009, p. 43-52. Warsaw: National Institute of Cultural Heritage. ISSN 0029-8247. (in Polish)

- ↑ Maria Nietyksza, Witold Pruss: Zmiany w układzie przestrzennym Warszawy. In: Irena Pietrza-Pawłowska (editor): Wielkomiejski rozwój Warszawy do 1918 r.. Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Książka i Wiedza, p. 43. 1973. (in Polish)

- ↑ Rozporządzenie Rady Ministrów z dnia 5 maja 1951 r. w sprawie zmiany granic miasta stołecznego Warszawy. Archived 2023-04-03 at the Wayback Machine. In: Dzienik Ustaw z 1951 r., no. 27, position 199. Warsaw. 1951. (in Polish)

- ↑ Elektryfikacja Warszawskiego Węzła Kolejowego. In: Stanisław Plewako: Elektryfikacja PKP na przełomie wieków XX i XXI: w siedemdziesiątą rocznicę elektryfikacji PKP. Warsaw: Z. P. Poligrafia, 2006, p. 76–79. ISBN 978-83-922944-6-7. (in Polish)

- ↑ Czesław Grzelak, Henryk Stańczyk: Kampania polska 1939 roku. Początek II wojny światowej. Warsaw: Oficyna Wydawnicza Rytm, 2005, p. 5, 385. ISBN 83-7399-169-7. (in Polish)

- ↑ Władysław Bartoszewski: 1859 dni Warszawy. Kraków: Wydawnictwo Znak, 2008, p. 67. ISBN 978-83-240-1057-8. (in Polish)

- ↑ Władysław Bartoszewski: Warszawski pierścień śmierci 1939–1944. Warsaw: Interpress, 1970, p. 201–211. (in Polish)

- ↑ Piotr Gursztyn: Rzeź Woli. Zbrodnia nierozliczona. Warsaw: Wydawnictwo DEMART SA, 2014. ISBN 978-83-7427-869-0. (in Polish)

- ↑ "Powstańcze miejsca pamięci oraz miejsca kaźni Polaków na Woli". wola.waw.pl (in Polish). Archived from the original on 2014-12-15. Retrieved 2023-05-11.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ↑ Michał Krasucki: Warszawskie dziedzictwo postindustrialne. Warsaw: Fundacja Hereditas, 2011, p. 240, 260, 277. ISBN 978-83-931723-5-1. (in Polish)