| Notodiscus hookeri | |

|---|---|

| |

| A live Notodiscus hookeri is eating lichen Usnea taylorii. | |

| |

| Apical view of the shell of holotype of Notodiscus hookeri heardensis | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| (unranked): | clade Heterobranchia

clade Euthyneura |

| Superfamily: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | Notodiscus |

| Species: | N. hookeri |

| Binomial name | |

| Notodiscus hookeri | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Helix hookeri Reeve, 1854 | |

Notodiscus hookeri is a species of small air-breathing land snail, a terrestrial gastropod mollusk in the family Charopidae.[2] This snail lives on islands in the sub-Antarctic region. Its shell is unique among land snails in that the organic shell layers contain no chitin.

Taxonomy

This species was described under the name Helix hookeri by an English conchologist Lovell Augustus Reeve in 1854.[1] The specific name hookeri is in honor of English botanist Joseph Dalton Hooker, who collected this snail during the Antarctic expedition led by James Clark Ross.[1] Reeve's type description reads in Latin and in English language as follows:[1]

Species 1474 (Mus. Brit.)

Helix hookeri. Hel. testá mediocriter umbilicatá, orbuculari-depressá, sordidè olivaceá, subirrigulariter rugoso-striatá; spirá subplanulatá, suturis impressis; anfractibus quatuor, convexis; aperturá lunato-circulari, labro simplici.

Hooker's Helix. Shell moderately umbilicated, orbicularly depressed, dull olive, rather irregularly roughly striated; spire rather flat, with sutures impressed; whorls four, convex; aperture lunar-circular, lip simple.

Hab. Kerguelen's Land; Dr. J. D. Hooker.

A small depressed species collected by Dr. Hooker in the Antarctic Expedition of the Erebus and Terror, peculiarly characterized by the sombre olive-horny coating ofPaludina and Ampullaria.

Henry Augustus Pilsbry classified this species as Helix hookeri in 1887[3] or within the genus Amphidoxa as Amphidoxa hookeri within the family Endodontidae in 1894.[4]

Also Alan Solem classified this species within the family Endodontidae in 1968.[5]

A subspecies Notodiscus hookeri heardensis Dell, 1964[6] was recognized in Heard Island.[7]

Distribution

Notodiscus hookeri has a wide distribution in the sub-Antarctic region.[2] It is the only native terrestrial gastropod species found in the South Indian Ocean islands and archipelagos, and also in the South Atlantic Province:

South Indian Province:

- Crozet Islands.[2] For example, Notodiscus hookeri is the only terrestrial snail among about 50 species of native invertebrates in the Crozet Islands.[2]

- Kerguelen Islands[2]

- Heard Island[2]

- Prince Edward Islands[2]

South Atlantic Province:

- Notodiscus hookeri is limited to South Georgia in the South Atlantic Province.[2]

The type locality is the Kerguelen Islands.[1]

The land snail Notodiscus hookeri is not an endangered or a protected species.[2]

Shell description

The shell growth does not stop on reaching sexual maturity, but decelerates considerably, with the biggest shells measuring 7.5–7.7 mm in size.[2]

Large intraspecific variations in shell morphometrics have been reported for this species on Possession Island,[7] with endemic variants being described as local adaptations to environmentally distinct islands.[2]

The shape of the shell is depressed. The umbilicus is open.

The width of the adult shell is up to 7.5-7.77 mm.[2] The weight of the snail of the shell length 6.13 mm is 52.88 mg.[8]

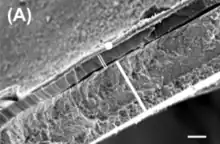

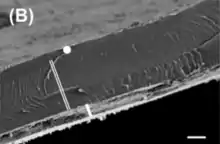

The micro structure of the shell was analysed by Charrier et al. (2013).[2] Their study was the first to demonstrate that gastropod shell micro structure responds to environmental heterogeneity, leading to the formation of ecophenotypes.[2] The adults of Notodiscus hookeri have evolved into two ecophenotypes, which the authors referred as MS (mineral shell) and OS (organic shell):[2]

- The MS-ecophenotype is characterised by a thick but small mineralised shell.[2] This ecophenotype is primarily found along the coastline, and may be associated with the presence of exchangeable calcium in the clay minerals of the soils.[2]

- The OS-ecophenotype is characterised by a thin but large organic shell.[2] This ecophenotype is primarily found at high altitudes in the mesic and xeric fell-fields, in soils with large particles that lack clay and exchangeable calcium.[2] Snails of the OS-ecophenotype are characterised by thinner and larger shell sizes compared to snails of the MS-ecophenotype, indicating a trade-off between mineral thickness and shell size.[2] The OS-ecophenotype has a highly flexible shell.[2]

Notodiscus hookeri has unique[2] shell micro-scale structure among gastropods:

- A dense and homogeneous organic layer is loosely attached to the upper periostracum and the inner mineral layer.[2]

- In the organic layer of the shell, there is prevalence of glycine-rich proteins (glycine, leucine, isoleucine, valine), and an absence of chitin.[2] Almost all other gastropods with reduced shells have chitin.[2] The only other known example of the absence of chitin is the internal shell of the slug Ariolimax columbianus.[9][2]

Ecology

This land snail is a gregarious species that lives under moist stones, moss and wet vegetation; however, it is also widespread in fell-field areas, which are characterised by very low vegetation cover.[2] This snail live in relatively simple ecosystems, that is caused by harsh environmental conditions on subantarctic islands.[8] It is a litter-dwelling species.[8]

The soil is known to be a nutrient resource for Notodiscus hookeri, since this species has been found to significantly increase calcium release in solutions derived from plant litter.[2]

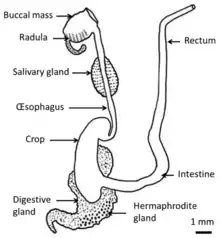

Notodiscus hookeri exclusively feeds on lichens such as Orceolina kerguelensis, Usnea taylorii and Pseudocyphellaria crocata.[8] Notodiscus hookeri appears as a generalist lichen feeder able to consume toxic metabolite-containing lichens.[8]

Hatchlings have a shell width of < 2.0 mm.[2] Juveniles have a shell width of about 2.0-4.0 mm.[2] Adults have a shell width larger than 4.0 mm.[2]

The biology of this species is poorly known.[2]

On a stamp

Notodiscus hookeri was depicted on the 2012 €0.60 French Southern and Antarctic Lands postal stamp.[10]

See also

References

This article incorporates public domain text from the reference[1] and (modified) CC-BY-4.0 text from references[2][8]

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Reeve L. A. (1854). Conchologia iconica, or, Illustrations of the shells of molluscous animals 7: Species 1474, plate 208, figure 1474.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 Charrier M., Marie A., Guillaume D., Bédouet L., Le Lannic J., Roiland C., Berland S., Pierre J.-S., Le Floch M., Frenot Y. & Lebouvier M. (2013). "Soil Calcium Availability Influences Shell Ecophenotype Formation in the Sub-Antarctic Land Snail, Notodiscus hookeri". PLoS ONE 8(12): e84527. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0084527

- ↑ Pilsbry H. A. (1887). Manual of Conchology. Second series: Pulmonata. Volume 3. Helicidae – Volume I. (2)3: page 48.

- ↑ Pilsbry H. A. (1894). Manual of Conchology. Second series: Pulmonata. Volume 9. Helicidae – Volume VII. (2)9: page 39, plate 5, figure 83.

- ↑ Solem A. (1968). "The subantarctic land snail, Notodiscus hookeri (Reeve, 1854) (Pulmonata, Endodontidae)". Proceedings of the Malacological Society of London 38(3): 251-266. PDF (subscription required)

- ↑ Dell R. K. (1964). "Land snails from Subantarctic Islands". Transactions and Proceedings of the Royal Society of New Zealand 11: 167-173.

- 1 2 Madec L. & Bellido A. (2007). "Spatial variation of shell morphometrics in the subantarctic snail Notodiscus hookeri from Crozet and Kerguelen Islands". Polar Biology 30: 1571-1578. doi:10.1007/s00300-007-0318-7.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Gadea, A., Le Pogam, P., Biver, G., Boustie, J., Le Lamer, A. C., Le Dévéhat, F., & Charrier, M. (2017). "Which Specialized Metabolites Does the Native Subantarctic Gastropod Notodiscus hookeri Extract from the Consumption of the Lichens Usnea taylorii and Pseudocyphellaria crocata?". Molecules 22(3): 425. doi:10.3390/molecules22030425

- ↑ Meenakshi V. R. & Scheer B. T. (1970). "Chemical studies of the internal shell of the slug, Ariolimax columbianus (Gould) with special reference to the organic matrix". Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology 34(4): 953-957. doi:10.1016/0010-406X(70)91018-2.

- ↑ TF004.12, accessed 15 February 2014.

External links

- Pugh P. J. A. & Scott B. (2002). "Biodiversity and biogeography of non-marine Mollusca on the islands of the Southern Ocean". Journal of Natural History 36(8): 927-952. doi:10.1080/00222930110034562.

- Pugh P. J. A. & Smith R. I. L. (2011). "Notodiscus (Charopidae) on South Georgia: some implications of shell size, shell shape, and site isolation in a singular sub-Antarctic land snail". Antarctic Science 23(5): 442-448. doi:10.1017/S0954102011000289.

- photo of the snail

- photo of the shell