.jpg.webp)

Niello /niːˈɛloʊ/[1][2] is a black mixture, usually of sulphur, copper, silver, and lead,[3] used as an inlay on engraved or etched metal, especially silver. It is added as a powder or paste, then fired until it melts or at least softens, and flows or is pushed into the engraved lines in the metal. It hardens and blackens when cool, and the niello on the flat surface is polished off to show the filled lines in black, contrasting with the polished metal around it.[4] It may also be used with other metalworking techniques to cover larger areas, as seen in the sky in the diptych illustrated here. The metal where niello is to be placed is often roughened to provide a key. In many cases, especially in objects that have been buried underground, where the niello is now lost, the roughened surface indicates that it was once there.

Statistical consideration

Niello was used on a variety of objects including sword hilts, chalices, plates, horns, adornment for horses, jewellery such as bracelets, rings, pendants, and small fittings such as strap-ends, purse-bars, buttons, belt buckles and the like.[5] It was also used to fill in the letters in inscriptions engraved on metal. Periods when engraving filled in with niello has been used to make full images with figures have been relatively few, but include some significant achievements. In ornament, it came to have competition from enamel, with far wider colour possibilities, which eventually displaced it in most of Europe.

The name derives from the Latin nigellum for the substance,[6] or nigello or neelo, the medieval Latin for black.[7] Though historically most common in Europe, it is also known from many parts of Asia and the Near East.[8]

Bronze Age

There are a number of claimed uses of niello from the Mediterranean Bronze Age, all of which have been the subjects of disputes as to the actual composition of the materials used, that have not been conclusively settled, despite some decades of debate. The earliest claimed use of niello appears in late Bronze Age Byblos in Syria, around 1800 BC, in inscriptions in hieroglyphs on scimitars.[10] In Ancient Egypt it appears a little later, in the tomb of Queen Ahhotep II, who lived about 1550 BC, on a dagger decorated with a lion chasing a calf in a rocky landscape in a style that shows Greek influence, or at least similarity to the roughly contemporary daggers from Mycenae, and perhaps other objects in the tomb.[11]

History

At about the same time of c.1550 BC it appears on several bronze daggers from shaft grave royal tombs at Mycenae (in Grave Circle A and Grave Circle B), especially in long thin scenes running along the centre of the blade. These show the violence typical of the art of Mycenaean Greece, as well as a sophistication in both technique and figurative imagery that is startlingly original in a Greek context. There are a number of scenes of lions hunting and being hunted, attacking men and being attacked; most are now in the National Archaeological Museum, Athens.[12]

These are in a mixed-media technique often called metalmalerei (German: "painting in metal"), which involves using gold and silver inlays or applied foils with black niello and the bronze, which would originally have been brightly polished. As well as providing a black colour, the niello was also used as the adhesive to hold the thin gold and silver foils in place.[13]

Byblos in Syria, where niello first appears, was something of an Egyptian outpost on the Levant, and many scholars think that it was highly-skilled metalworkers from Syria who introduced the technique to both Egypt and Mycenaean Greece. The iconography can most easily be explained by some combination of influence from the broader traditions of Mesopotamian art where somewhat comparable imagery had been produced for over a thousand years in cylinder seals and the like, and some (such as the physique of the figures) from Minoan art, although no early niello has been found on Crete.[14]

A decorated metal cup, the "Enkomi Cup" from Cyprus has also been claimed to use niello decoration. However, controversy has continued since the 1960s as to whether the material used on all these pieces actually is niello, and a succession of increasingly sophisticated scientific tests have failed to provide evidence of the presence of the sulphurous compounds which define niello.[15] It has been suggested that these artefacts, or at least the daggers, use in fact a technique of patinated metal that may be the same as the Corinthian bronze known from ancient literature, and is similar to the Japanese Shakudō.[16]

Roman, Byzantine and medieval

Niello is then hardly found until the Roman period; or perhaps it first appears around this point.[17] Pliny the Elder (AD 23–79) describes the technique as Egyptian, and remarks the oddness of decorating silver in this way.[18] Some of the earliest uses, from 1–300 AD, seem to be small statuettes and brooches of big cats, where niello is used for the stripes of tigers and the spots on panthers; these were very common in Roman art, as creatures of Bacchus. The animal repertoire of Roman Britain was somewhat different, and provides brooches with niello stripes on a hare and a cat.[19] From about the 4th century, it was used for ornamental details such as borders and for inscriptions in late Roman silver, such as a dish and bowl in the Mildenhall Treasure and pieces in the Hoxne Hoard, including Christian church plate. It was often used on spoons, which were often inscribed with the owner's name, or later crosses. This type of use continued in Byzantine metalwork, from where it passed to Russia.

It is very common in Anglo-Saxon metalwork, with examples including the Tassilo Chalice, Strickland Brooch, and the Fuller Brooch,[8] generally forming the background for motifs carried in the metal, but also used for rather crude geometric decoration of spots, triangles and stripes on small relatively everyday fittings such as strap-ends in base metal. There is similar use in Celtic, Viking, and other types of Early Medieval jewellery and metalwork, especially in northern Europe.[20] Similar uses continued in the traditional styles of jewellery of the Middle East until at least the 20th century. The Late Roman buckle from Gaul illustrated here shows a relatively high quality early example of this sort of decoration.

In Romanesque art colourful champlevé enamel largely replaced it, although it continued to be used for small highlights of ornament, and some high quality Mosan art began to use it for small figurative images as part of large pieces, very often applied as plaques. These began to exploit the possibilities of niello for carrying a precise graphic style. The back of the Ottonian Imperial Cross (1020s) has outline engravings of figures filled with niello, the black lines forming the figures on a gold background. Later Romanesque pieces began to use a more densely engraved style, where the figures are mostly carried by the polished metal, against a black background. Romanesque champlevé enamel was applied to a cheap copper or copper alloy form, which was a great advantage, but for some pieces the prestige of precious metal was desired, and a small number of nielloed silver pieces from c. 1175–1200 adopt the ornamental vocabulary developed in Limoges enamel.[21]

A group of high-quality pieces apparently originating in the Rhineland, which use both niello and enamel, include what may be the earliest reliquary with scenes of the murder and burial of Thomas Becket, probably from a few years after his death in 1170 (The Cloisters). Eight large nielloed plaques decorate the sides and roof, six with figures seen close-up at less than half-length, in a very different style from the cruder full-length figures in the many Limoges enamel equivalent reliquaries.[22]

Gothic art from the 13th century continued to develop this pictorial use of niello, which reached its high point in the Renaissance.[8] Niello continued to be widely used for simple ornament on small pieces, though at the top end goldsmiths were more likely to use black enamel to fill inscriptions on rings and the like. Niello was also used on plate armour, in this case over etched steel, as well as weapons.

Roman brooch in the form of a panther, copper alloy inlaid with silver and niello, 100-300

Roman brooch in the form of a panther, copper alloy inlaid with silver and niello, 100-300 Silver-plated fancy bronze spoon with a panther, Roman, 3rd-4th century, found in France

Silver-plated fancy bronze spoon with a panther, Roman, 3rd-4th century, found in France Mount for Spear Shaft, Late Roman, c. 400

Mount for Spear Shaft, Late Roman, c. 400 Gold Byzantine wedding ring with scenes from the Life of Christ, 6th century

Gold Byzantine wedding ring with scenes from the Life of Christ, 6th century Niello ornamentation and inscription on a silver 6th-century liturgical strainer, France

Niello ornamentation and inscription on a silver 6th-century liturgical strainer, France Monogram in the centre of an otherwise plain Byzantine dish, 610-613

Monogram in the centre of an otherwise plain Byzantine dish, 610-613 The Fuller Brooch, Anglo-Saxon, 9th century

The Fuller Brooch, Anglo-Saxon, 9th century.jpg.webp) Anglo-Saxon silver strap end in the Trewhiddle style, now only with traces of niello left. 9th century

Anglo-Saxon silver strap end in the Trewhiddle style, now only with traces of niello left. 9th century.JPG.webp) Niello-filled lettering on the side of the Imperial Cross, c. 1024-25

Niello-filled lettering on the side of the Imperial Cross, c. 1024-25 Niello-filled paten from Trzemeszno, Poland, fourth quarter of the 12th century

Niello-filled paten from Trzemeszno, Poland, fourth quarter of the 12th century

Renaissance niello

Some Renaissance goldsmiths in Europe, such as Maso Finiguerra and Antonio del Pollaiuolo in Florence, decorated their works, usually in silver, by engraving the metal with a burin, after which they filled up the hollows produced by the burin with a black enamel-like compound made of silver, lead and sulphur. The resulting design, called a niello, was of much higher contrast and thus much more visible. Sometimes niello decoration was incidental to the objects, but some pieces such as paxes were effectively pictures in niello. A range of religious objects such as crucifixes and reliquaries might be decorated in this way, as well as secular objects such as knife handles, rings and other jewellery, and fittings such as buckles. It appears that niello-work was probably a specialist activity of some goldsmiths, not practiced by others, and most work came from Florence or Bologna.[23]

Niellists were important in the history of art because they had developed skills and techniques that transferred easily to engraving plates for printmaking on paper, and nearly all the earliest engravers were trained as goldsmiths, enabling the new art medium to develop very quickly. At least in Italy, some of the very earliest engraved prints were in fact made by treating a silver object intended for niello as a printing plate with ink, before the niello was added. These are known as "niello prints", or in the cautious words of modern curators, "printed from a plate engraved in the niello manner";[24] in later centuries, after a collector's market grew up, many were forgeries. The genuine Renaissance prints were probably made mainly as a record of his work by the goldsmith, and perhaps as independent art objects.[25]

By the late 16th century relatively little use was made of niello, especially to create pictures, and a different type of mastic that could be used in much the same way for contrasts in decoration was devised, so European pictorial use was largely restricted to Russia, except for some watches, guns, instruments and the like.[8] Niello has continued to be used sometimes by Western jewellers.

.JPG.webp) Florentine pax, early 1460s, probably by Maso Finiguerra

Florentine pax, early 1460s, probably by Maso Finiguerra.jpg.webp) German pax, c. 1490, circle of the engraver Martin Schongauer, showing a close relationship to the printed engraving style.

German pax, c. 1490, circle of the engraver Martin Schongauer, showing a close relationship to the printed engraving style. Niello print, 2 inches high, 1500-1520. Orpheus seated and playing his lyre, by Peregrino da Cesena

Niello print, 2 inches high, 1500-1520. Orpheus seated and playing his lyre, by Peregrino da Cesena Watch case, London around 1700

Watch case, London around 1700

Kievan Rus and Russia

During the 10th to 13th century AD, Kievan Rus craftsmen possessed a high degree of skill in jewellery making. John Tsetses, a 12th-century Byzantine writer, praised the work of Kievan Rus artisans and likened their work to the creations of Daedalus, the highly skilled craftsman of Greek mythology.

The Kievan Rus technique for niello application was first shaping silver or gold by repoussé work, embossing, and casting. They would raise objects in high relief and fill the background with niello using a mixture of red copper, lead, silver, potash, borax, sulphur which was liquefied and poured into concave surfaces before being fired in a furnace. The heat of the furnace would blacken the niello and make the other ornamentation stand out more vividly.

Nielloed items were mass-produced using moulds that still survive today and were traded with Greeks, the Byzantine Empire, and other peoples that traded along the trade route from the Varangians to the Greeks.

During the Mongol invasion from 1237 to 1240 AD, nearly all of Kievan Rus was overrun. Settlements and workshops were burned and razed and most of the craftsmen and artisans were killed. Afterwards, skill in niello and cloisonné enamel diminished greatly. The Ukrainian Museum of Historic Treasures, located in Kiev, has a large collection of nielloed items mostly recovered from tombs found throughout Ukraine.[26]

Later, Veliky Ustyug in North Russia, Tula and Moscow produced high quality pictorial niello pieces such as snuff boxes in contemporary styles such as Rococo and Neoclassicism in the late 18th and early 19th centuries; by then Russia was virtually the only part of Europe regularly using niello in fashionable styles.

Russian sacrament box; early 18th century

Russian sacrament box; early 18th century Rococo table snuff-box with shell body. Probably Veliky Ustyug, c. 1745–50

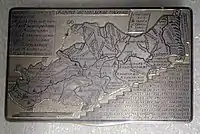

Rococo table snuff-box with shell body. Probably Veliky Ustyug, c. 1745–50 Snuffbox with distance-finder, Veliky Ustyug, 1823

Snuffbox with distance-finder, Veliky Ustyug, 1823 Russian tumbler, 1854

Russian tumbler, 1854

Islamic world

.jpg.webp)

Pre-Islamic period

Niello was rarely used in Sasanian metalwork, which could use it inventively. The Metropolitan Museum of Art has Sasanian shallow bowls or dishes where in one case it forms the stripes on a tiger,[27] and in another the horns and hoofs of goats in relief, as well as parts of the king's weapons. This relief use of niello seems to be paralleled from this period in only one piece of Byzantine silver.[28]

Islamic period

In the early Islamic world silver, though continuing in use for vessels at the courts of princes, was much less widely used by the merely wealthy. Instead, vessels of the copper alloys bronze and brass included inlays of silver and gold in their often elaborate decoration, leaving less of a place for niello. Other black fillings were also used, and museum descriptions are often vague about the actual substances involved.

The famous "Baptistère de Saint Louis", c. 1300, a Mamluk basin of engraved brass with gold, silver and niello inlay, which has been in France since at least 1440 (Louis XIII of France and perhaps other kings were baptized in it; now Louvre), is one example where niello is used. Here niello is the background to the figures and the arabesque ornament around them, and used to fill the lines in both.

It is used on the locking bars of some ivory boxes and caskets, and perhaps continued more widely in use on weapons, where it is certainly found in later centuries from which more material survives. It is common in the decoration of the scabbards and hilts of the large daggers called khanjali and qama traditionally carried by all males in the Caucasus region (whether Muslim or Christian). It was also used to decorate handguns when they came into use. Until modern times relatively simple niello was common on the jewellery of the Levant, used in much the same way as in medieval Europe.

Sasanian dish; the king hunting rams. c. 450-550

Sasanian dish; the king hunting rams. c. 450-550 Niello accents on the lock of the ivory "Box of Zamora", 900-964, Al-Andaluz

Niello accents on the lock of the ivory "Box of Zamora", 900-964, Al-Andaluz Seljuk dish, c. 1200

Seljuk dish, c. 1200.jpg.webp) 15th century box, brass with silver and niello, perhaps from Egypt

15th century box, brass with silver and niello, perhaps from Egypt 16-17th century Ottoman cavalvry shield with niello on central boss

16-17th century Ottoman cavalvry shield with niello on central boss Ntello ihe top zonarea a helmet from Crimea or South Russia, 1818–19

Ntello ihe top zonarea a helmet from Crimea or South Russia, 1818–19_with_Scabbard_MET_sfsb26.35.8a(5-15-07)s2d1.jpeg.webp)

Thai jewellery

Nielloware jewellery[29] and related items from Thailand were popular gifts from American soldiers taking "R&R" in Thailand to their girlfriends/wives back home from the 1930s to the 1970s. Most of it was completely handmade jewellery.

The technique is as follows: the artisan would carve a design into the silver, leaving the figure raised by carving out the "background". He would then use the niello inlay to fill in the "background". After being baked in an open fire, the alloy would harden. It would then be sanded smooth and buffed. Finally, a silver artisan would add minute details by hand. Filigree was often used for additional ornamentation. Nielloware is classified as only being black and silver coloured. Other coloured jewellery originating during this time uses a different technique and is not considered niello.

Many of the characters shown in nielloware are characters originally found in the Hindu legend Ramayana. The Thai version is called Ramakien. Important Thai cultural symbols were also frequently used.

Ingredients and technique

Various slightly different recipes are found by modern scientific analysis, and historic accounts. In early periods, niello seems to have been made with a single sulphide, that of the main metal of the piece, even if it was gold (which would be difficult to handle). Copper sulphide niello has only been found on Roman pieces, and silver sulphide is used on silver.[30] Later a mixture of metals was used; Pliny gives a mixed sulphide recipe with silver and copper, but seems to have been some centuries ahead of his time, as such mixtures have not been identified by analysis on pre-medieval pieces. Most Byzantine and early medieval pieces analysed are silver-copper, while silver-copper-lead pieces appear from about the 11th century onwards.[31]

The Mappae clavicula of about the 9th century, Theophilus Presbyter (1070–1125) and Benvenuto Cellini (1500–1571) give detailed accounts, using silver-copper-lead mixtures with slightly different ratios of ingredients, Cellini using more lead.[32] Typical ingredients have been described as: "sulfur with several metallic ingredients and borax";[6] "copper, silver, and lead, to which had been added sulphur while the metal was in fluid form ... [the design] was then brushed over with a solution of borax..."[33]

While some recipes talk of using furnaces and muffles to melt the niello, others just seem to use an open fire. The necessary temperatures vary with the mixture; overall silver-copper-lead mixtures are easier to use. All mixtures have the same black appearance after work is completed.[34]

See also

- Damascening

- Yemenite silversmithing (carries a full description on how niello was applied to jewellery in Yemen)

- Kubachi silver

Notes

- ↑ Stormonth, James (25 January 1895). "A Dictionary of the English Language Pronouncing, Etymological, and Explanatory ..." Blackwood – via Google Books.

- ↑ Donald, James (25 January 1879). "Chamber's English Dictionary, Pronouncing, Explanatory, and Etymological: With Vocabularies Or Scottish Words and Phrases, Americanisms, &c". Chambers – via Google Books.

- ↑ Ingredients vary; see below

- ↑ Levinson, 528; Craddock

- ↑ Levinson, 528; Osborne, 595

- 1 2 Levinson, 528

- ↑ Osborne, 594

- 1 2 3 4 Osborne, 595

- ↑ NAMA 394, full image

- ↑ Smith and Stevenson, 114

- ↑ Smith and Stevenson, 114 (the identity of the queen in this burial has undergone revision in recent decades); Lucas and Harris, 250–251 for a more sceptical account.

- ↑ Thomas, 178–182; Dickinson, 99–100

- ↑ Thomas, 179–182; Dickinson, 99–100

- ↑ Thomas, 171–182, 193; Dickinson, 99–100

- ↑ Maryon, 161; Craddock; Enkomi Bowl

- ↑ Craddock and Giumlia-Mair, 109–120

- ↑ Craddock; Maryon, 161

- ↑ Lucas and Harris, 249–250

- ↑ Johns, 175–177

- ↑ Solberg, S., (2003) Jernalderen I Norge, page 158. Oslo, Norway: J.W. Cappelens Forlag

- ↑ Zarnecki, 287, 283, 285

- ↑ Zarnecki, 302

- ↑ Levinson, 528–529; Landau, 98–99; Osborne, 595

- ↑ "niello print | British Museum". The British Museum.

- ↑ Levinson, 528–529; Landau, 26, 67–68

- ↑ Ganina

- ↑ In a way similar to the Roman "Hoxne Tiger" of the Hoxne Hoard

- ↑ Prudence Oliver Harper, Silver Vessels of the Sasanian Period: Royal imagery, 64–65 (see note 128 in particular), 1981, Metropolitan Museum of Art, ISBN 0870992481, 9780870992483, google books

- ↑ Graham, Walter Armstrong (1913). Siam: A Handbook of Practical, Commercial, and Political Information. F. G. Browne. p. 435.

- ↑ Maryon, 161–162; Craddock

- ↑ Craddock; Newman

- ↑ Maryon, 162–164; Newman; Craddock

- ↑ Osborne, 595 (following Theophilus Presbyter)

- ↑ Craddock

References

- Craddock, P. T., "Metal" V. 4, Grove Art Online, Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press. Web. 1 Oct. 2017, Subscription required

- Craddock, Paul and Giumlia-Mair, Allessandra, "Hsmn-Km, Corinthian bronze, Shakudo: black patinated bronze in the ancient world", Chapter 9 in Metal Plating and Patination: Cultural, technical and historical developments, Ed. Susan La-Niece and Craddock, P. T., 2013, Elsevier, ISBN 1483292061, 9781483292069, google books

- Dickinson, Oliver et al., The Aegean Bronze Age, 1994, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0521456649, 9780521456647, The Aegean Bronze Age

- Ganina, O. (1974), The Kiev museum of historic treasures (A. Bilenko, Trans.). Kiev, Ukraine: Mistetstvo Publishers

- Johns, Catherine, The Jewellery of Roman Britain: Celtic and Classical Traditions, 1996, Psychology Press, ISBN 1857285662, 9781857285666, google books

- Landau, David, and Parshall, Peter. The Renaissance Print, Yale, 1996, ISBN 0300068832

- Levinson Jay A. (ed.), Early Italian Engravings from the National Gallery of Art, National Gallery of Art, Washington (Catalogue), 1973, LOC 7379624

- Maryon, Herbert, Metalwork and Enamelling, 1971 (5th ed.). Dover, New York, ISBN 0486227022, google books

- Lucas A and Harris J. Ancient Egyptian Materials and Industries, 2012 (reprint, 1st edn 1926), Courier Corporation, ISBN 0486144941, 9780486144948, google books

- "Newman": R. Newman, J. R. Dennis, & E. Farrell, "a Technical Note on Niello", Journal of the American Institute for Conservation, 1982, Volume 21, Number 2, Article 6 (pp. 80 to 85), online text

- Osborne, Harold (ed), "Niello", in The Oxford Companion to the Decorative Arts, 1975, OUP, ISBN 0198661134

- Smith, W. Stevenson, and Simpson, William Kelly. The Art and Architecture of Ancient Egypt, 3rd edn. 1998, Yale University Press (Penguin/Yale History of Art), ISBN 0300077475

- Thomas, Nancy R., "The Early Mycenaean Lion up to Date", pp. 189–191, in Charis: Essays in Honor of Sara A. Immerwahr, Hesperia (Princeton, N.J.) 33, 2004, ASCSA, ISBN 0876615337, 9780876615331, google books

- Zarnecki, George and others; English Romanesque Art, 1066–1200, 1984, Arts Council of Great Britain, ISBN 0728703866

Further reading

- Dittell, C. (2012), Overview of Siam Sterling Nielloware, Tampa, FL (or Survey of Siam Sterling Nielloware, (E-Book), Bookbaby Publishers)

- Giumlia-Mair, A. 2012. "The Enkomi Cup: Niello versus Kuwano", in V. Kassianidou & G. Papasavvas (eds.) Eastern Mediterranean Metallurgy and Metalwork in the Second Millennium BC. A Conference in Honour of James D. Muhly, Nicosia, 10–11 October 2009, 107–116. Oxford & Oakville: Oxbow Books.

- Northover P. and La Niece S., "New Thoughts on Niello", in From Mine to Microscope: Advances in the Study of Ancient Technology, eds. Ian Freestone, Thilo Rehren, Shortland, Andrew J., 2009, Oxbow Books, ISBN 1782972773, 9781782972778, google books

- Oddy, W., Bimson, M., & La Niece, S. (1983). "The Composition of Niello Decoration on Gold, Silver and Bronze in the Antique and Mediaeval Periods". Studies in Conservation, 28(1), 29–35. doi:10.2307/1506104, JSTOR

External links

- "Nielloware in Thailand". Archived from the original on 12 January 2015.

- E.Brepohls article on niello work